John Loring (Royal Navy officer, died 1808)

| John Loring | |

|---|---|

| Died |

9 November 1808 Fareham, Hampshire |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

|

| Rank | Post-Captain |

| Commands held |

|

| Battles/wars | |

| Relations |

Joshua Loring (grandfather) John Wentworth Loring (cousin) |

John Loring (died 9 November 1808) was an officer in the Royal Navy who served during the American War of Independence and the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars.

Loring was a descendant of a naval officer, with his first-cousin also making a successful career in the Navy. John Loring saw some service in the American War of Independence, being promoted to lieutenant during the war, but remained at this rank until shortly after the outbreak of the French Revolutionary Wars. He went out to the Mediterranean with his first command and served at the Siege of Toulon under Admiral Lord Hood. His ship was under repair when the city fell to French forces, and he was forced to burn her to keep her out of enemy hands. His service continued though, and he became acting-captain of the 74-gun HMS Bellerophon for a brief period before a new officer was appointed to replace her original captain.

Loring went on to command several ships of the line, before once again taking over HMS Bellerophon, this time as a full post-captain. He served in the West Indies, and distinguished himself after the outbreak of the Napoleonic Wars by superintending the Blockade of Saint-Domingue, with the post of commodore. During the blockade a number of French warships, merchants and privateers were taken by his squadron, and he oversaw the surrender and evacuation of the French garrison of Haiti. He finally returned to Britain in 1805 and paid his ship off. He does not appear to have served in a seagoing command again, but commanded the Plymouth guardship for two years and took up a shore-based position as commander of a unit of the Sea Fencibles. He died in 1808, still with the rank of captain. He was succeeded by at least two sons, who followed their father into the navy.

Family and first commands

Loring's origins are obscure. He was the grandson of Joshua Loring, a naval officer who had served in North America during the Seven Years' War and had commanded a squadron on the Great Lakes during the American War of Independence. He was also the first-cousin of John Wentworth Loring, who also embarked on a naval career and rose to the rank of admiral.[1] John Loring was commissioned as a lieutenant on 3 December 1779. He still held this rank by the outbreak of the French Revolutionary Wars and in January 1793 was appointed to command the fireship HMS Conflagration.[2] Promoted to commander on 16 May 1793, he sailed Conflagration to the Mediterranean on 22 May and was part of Lord Hood's fleet at the occupation and siege of Toulon. She was under repair there when the city was evacuated, and was burnt on Hood's orders to avoid falling into French hands on 18 December 1793.[2] He returned to England and was given command of the 16-gun sloop HMS Hazard, which he served in from April 1794 until 1795.[3]

Loring was made acting-captain of the 74-gun HMS Bellerophon on 12 April 1796 while Bellerophon was serving off Ushant on the Brest blockade.[4] Bellerophon's nominal commander, Captain James Cranstoun, 8th Lord Cranstoun, had been appointed Governor of Grenada and left the ship to prepare to take up his post.[a] Loring was in command until being superseded by Cranstoun's replacement, Captain Henry D'Esterre Darby, on 11 September.[4] He seems to have left the ship shortly after this and by October 1796 had presumably been promoted to captain as he commissioned the 32-gun HMS Proselyte and prepared her for service. He took her out to Jamaica in February 1797 and there had some success against privateers, capturing the French 6-gun privateer schooner Liberté later that year.[5]

In 1799 he is recorded as taking command of the 74-gun HMS Carnatic at Jamaica, holding the post until 1800.[6] He took over the 74-gun HMS Hannibal that year, but paid her off later in 1800.[7] He appears to have briefly commissioned the 98-gun HMS Prince in early November 1801, but had received a new appointment before the end of the month.[8]

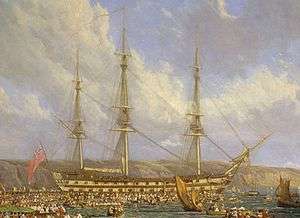

HMS Bellerophon

Loring was appointed to take over his former command, HMS Bellerophon, on 25 November 1801, superseding Captain Lord Garlies.[9] Bellerophon was serving at this time with the Channel Fleet, but in early 1802 Loring received new orders. Bellerophon was among five ships ordered to join Admiral John Duckworth's squadron in the West Indies, and having stored, she sailed from Torbay on 2 March 1802.[9][10] By the time of her arrival on 27 March, the Treaty of Amiens had been signed, and Britain and France were at peace. For the next eighteen months Bellerophon took part in cruises in the Jamaica Passage and escorted merchant convoys between Jamaica and Halifax.[11]

Bellerophon was in the West Indies when the Napoleonic Wars broke out in May 1803. Loring was appointed commodore of the British squadron, which quickly went on the offensive against French shipping in the Blockade of Saint-Domingue. The corvette Mignonne and a brig were captured in late June, after which the British patrolled off Cap-François.[9] On 24 July the squadron, made up of Bellerophon and the 74-gun ships HMS Elephant, HMS Theseus and HMS Vanguard, came across two French 74-gun ships, Duquesne and Duguay-Trouin, and the frigate Guerrière, attempting to escape from Cap-François.[12] The squadron gave chase, and on 25 July overhauled and captured Duquesne after a few shots were fired, while Duguay-Trouin and Guerrière managed to evade their pursuers and escape to France.[9] One man was killed aboard Bellerophon during the pursuit.[12] Loring remained blockading Cap-François until November, when the French commander of the garrison there, General Rochambeau, approached him and requested to be allowed to evacuate his men, which were being besieged by a native Haitian force led by Jean-Jacques Dessalines. The French were allowed to evacuate on three frigates, Surveillante, Clorinde and Vertu, and a number of smaller ships, and were escorted to Jamaica by the squadron.[9][13]

A particularly severe outbreak of malaria struck the ship in early February 1804, with 212 members of Bellerophon's crew falling ill. 17 died aboard the ship, while 100 had to be transferred to a shore-based hospital, where a further 40 died.[9][14] Loring was ordered to sail her back to Britain in June, escorting a large convoy, and arrived in the Downs on 11 August. He briefly paid her off and she was taken into Portsmouth Dockyard for a refit, before rejoining the Channel Fleet, still off Brest, and under the command of Admiral Sir William Cornwallis.[15] These duties lasted until early 1805, with Loring being superseded by Captain John Cooke on 24 April.[9][16]

Later life

Loring was then appointed to command the 112-gun HMS Salvador del Mundo, the Plymouth guardship, later that month, holding the post until being superseded in June 1807.[17] He was then in command of the Sea Fencibles covering the district between Emsworth and Calshot, and died in this post on 9 November 1808, still a captain, at Fareham, Hampshire.[1][18] He was described as "a most zealous, brave, and humane officer" in John Marshall's Royal Naval Biography.[18] He had at least two sons, who followed him into the Navy. Both survived him, with the eldest, John, dying of yellow fever while a midshipman aboard HMS Euryalus in 1820. His second son, Hector, became a commander.[1]

Notes

a. ^ Cranstoun died suddenly at his home at Bishop's Waltham on 22 September before he could take up his post.[19]

Citations

- 1 2 3 O'Byrne. A Naval Biographical Dictionary. p. 672.

- 1 2 Winfield. British Warships of the Age of Sail 1793–1814. p. 369.

- ↑ Winfield. British Warships of the Age of Sail 1793–1814. p. 235.

- 1 2 Goodwin. The Ships of Trafalgar. p. 67.

- ↑ Winfield. British Warships of the Age of Sail 1793–1814. p. 197.

- ↑ Winfield. British Warships of the Age of Sail 1793–1814. p. 53.

- ↑ Winfield. British Warships of the Age of Sail 1793–1814. p. 57.

- ↑ Winfield. British Warships of the Age of Sail 1793–1814. p. 24.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Goodwin. The Ships of Trafalgar. p. 68.

- ↑ Cordingly. Billy Ruffian. p. 159.

- ↑ Cordingly. Billy Ruffian. p. 163.

- 1 2 Cordingly. Billy Ruffian. p. 165.

- ↑ Winfield. British Warships of the Age of Sail 1793–1814. p. 51.

- ↑ Cordingly. Billy Ruffian. p. 166.

- ↑ Cordingly. Billy Ruffian. p. 169.

- ↑ Cordingly. Billy Ruffian. p. 178.

- ↑ Winfield. British Warships of the Age of Sail 1793–1814. p. 16.

- 1 2 Marshall. Royal Naval Biography. p. 815.

- ↑ Cordingly. Billy Ruffian. p. 105.

References

- O'Byrne, William R. (1849). A Naval Biographical Dictionary: Comprising the Life and Services of Every Living Officer in Her Majesty's Navy, from the Rank of Admiral of the Fleet to that of Lieutenant, Inclusive. 1. J. Murray.

- Cordingly, David (2004). Billy Ruffian: The Bellerophon and the Downfall of Napoleon: The Biography of A Ship of the Line, 1782–1836. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 0-7475-6544-9.

- Goodwin, Peter (2005). The Ships of Trafalgar: The British, French and Spanish Fleets October 1805. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 1-84486-015-9.

- Marshall, John (2010) [1823]. Royal Naval Biography Supplement: Or, Memoirs of the Services of All the Flag-Officers, Superannuated Rear-Admirals, Retired-Captains, Post-Captains, and Commanders. 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-02265-1.

- Winfield, Rif (2008). British Warships in the Age of Sail 1793–1817: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. Seaforth. ISBN 1-86176-246-1.