British K-class submarine

| |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name: | K class |

| Builders: | |

| Operators: |

|

| In commission: | 1917—1931 |

| Planned: | 21 |

| Completed: | 17 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Submarine |

| Displacement: |

|

| Length: | 339 ft (103 m) |

| Beam: | 26 ft 6 in (8.08 m) |

| Draught: | 20 ft 11 in (6.38 m) |

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: |

|

| Range: |

|

| Complement: | 59 (6 officers and 53 ratings) |

| Armament: |

|

The K-class submarines were a class of steam-propelled submarines of the Royal Navy designed in 1913. Intended as large, fast vessels with the endurance and speed to operate with the battle fleet, they gained notoriety and the nickname of "Kalamity class", for being involved in many accidents. Of the 18 built, none was lost through enemy action but six sank in accidents. Only one ever engaged an enemy vessel, hitting a U-boat amidships though the torpedo failed to explode.

The class found favour with Commodore Roger Keyes, then Inspector Captain of Submarines, and with Admirals Sir John Jellicoe and Sir David Beatty, respectively Commander-in-Chief British Grand Fleet and Commander-in-Chief Battlecruiser Squadrons. Despite this, an early opponent of the class was Admiral Jacky Fisher, later First Sea Lord, who on the class' suggestion in 1913 had responded 'The most fatal error imaginable would be to put steam engines in submarines.'

In defence of the design it must be said that submarine technology was still in its infancy, that development was still at a similar early stage, and that the use of weapon (or tactics) requires at least as much thought and practical trial as the first two. Of course with hindsight the initial concept of a submarine (which we see today as a stealth weapon) maneuvering within the confines of a surface warship formation is at best a risky proposition; to a surface warship of today, a submarine (any submarine) is more likely to be seen as a threat than an ally.

Design and development

In 1913, a design outline was prepared for a new class of submarine which could operate with the surface fleet, sweeping ahead of it in a fleet action. Due to the superior size and power of the British Grand Fleet over the German High Seas Fleet it was intended that the submarines would get around the back of the enemy fleet and ambush it as it retreated.

The boats were to be 339 feet (103 m) long and displace 1,700 tons on the surface. It was chosen not to proceed until results from trials of two prototypes, Nautilus and Swordfish, had taken place. Following the trials with Nautilus, the slightly smaller J class was designed with a conventional diesel propulsion system.

By the middle of 1915 it was clear that the J class would not meet expectations; the triple-screw diesel configuration could only enable them to make 19 knots (35 km/h; 22 mph) on the surface — less than the 21 kn (39 km/h; 24 mph) needed to accompany the fleet (21 knots being the design speed of HMS Dreadnought). With the technology of the time it was judged the only way which submarines could be given sufficient surface speed to keep up with fleet was to make them steam turbine powered.

The K-class design was resurrected and 21 boats ordered in August at a cost of £340,000 each. Only 17 were constructed, the orders for the last four being cancelled and replaced by orders for the M class. Six improved versions, K22 to K28 were ordered in October 1917 but the end of the First World War meant that only K26 was completed.

The double hull design had a reserve buoyancy of 32.5 percent.[2] Although powered on the surface by oil-fired steam turbines, they were also equipped with an 800 hp (600 kW) diesel generator to charge the batteries and provide limited propulsive power in the event of problems with the boilers.

This pushed the displacement up to 1,980 tons on the surface, 2,566 tons submerged. They were equipped with four 18-inch (460 mm) torpedo tubes at the bow, two on either beam and another pair in a swivel mounting on the superstructure for night use. The swivel pair were later removed because they were prone to damage in rough seas. The K-class submarines were fitted with a proper deckhouse, built over and around the conning tower, which gave the crew much better protection than the canvas screens fitted in previous Royal Navy submarines.

The great size of the boats (compared to their predecessors) led to control and depth-keeping problems, particularly as efficient telemotor controls had not yet been developed. This was made worse by the estimated maximum diving depth of 200 feet (61 m) being much less than their overall length. Even a 10-degree angle on the 339-foot-long hull would cause a 59-foot (18 m) difference in depth of the bow and stern, and 30 degrees would produce 170 feet (52 m), which meant that while the stern would almost be on the surface, the bow would almost be at its maximum safe depth. The submarines were made more dangerous because the eight internal bulkheads were designed and tested during development to stand a pressure equivalent to only 70 feet (21 m), risking their collapse if the hull was compromised at a depth below this figure.

Service

K3 was the first of the class to be completed in May 1916, and trials revealed numerous problems, such as the aforementioned swivel tubes, and that their low freeboard and great length made them awkward to handle either surfaced or submerged. An early criticism of the class questioned the wisdom of combining such a large hull with so great a surface speed, producing a vessel with the pace of a destroyer and the turning circle of a battle-cruiser.

A dive from steam-powered surface operation normally required 30 minutes.[3] Minimum time needed to secure the main engines, shift to battery motors and dive under emergency conditions was nearly 5 minutes, which though better than the 15 minutes of the Swordfish prototype was considered barely adequate. The boiler fires were first extinguished to prevent submerged buildup of fumes: a complicated series of hydraulics and mechanical rods and levers lowered the twin funnels away from each other to a horizontal position in wells in the superstructure as well as simultaneously closing hatches over the funnel uptakes. The main intake ventilators were likewise closed along with sea water connections for condensers and boiler feed. It was considered that with their 24 knots (44 km/h; 28 mph) of speed the submarines could turn and outrun almost any threat if they were attacked on the surface, dispensing with a need for a rapid dive. This was perhaps wishful thinking, and just excused the fact that the record breaking 'crash dives' of the conventional boats (particularly the later World War II U boats) was unattainable.

The most oft quoted complaint about the class was that the submarines had 'Too many damned holes...' or openings in the pressure hull that required securing before a dive could commence, the majority of which gave air/sea access to parts of the boat normally unmanned whilst diving.

A more serious problem was the high temperatures in the boiler room which was to some extent alleviated by installing bigger fans. Steaming at speed tended to push the bow into the water making the already poor sea-keeping worse. To fix this a bulbous swan bow was added, which also incorporated a 'quick blowing' ballast tank to improve handling. Nevertheless, there were still problems; the most embarrassing being that in a heavy storm, sea water could enter the boat through the short twin funnels and put the boiler fires out. They suffered numerous accidents, largely caused by their poor manoeuvrability coupled with operating with the surface fleet, and which caused the incidence of the following:

- K13 sank on 19 January 1917 during sea trials when an intake failed to close whilst diving and her engine room flooded. She was eventually salvaged and recommissioned as K22 in March 1917.

- K1 collided with K4 off the Danish coast on 18 November 1917 and was scuttled to avoid capture.

- Two boats were lost in an incident known as the Battle of May Island on 31 January 1918. The cruiser HMS Fearless collided with the head of a line of submarines, K17, which sank in about 8 minutes, whilst other submarines behind her all turned to avoid her. K4 was struck by K6 which almost cut her in half and was then struck by K7 before she finally sank with all her crew. At the same time K22 (the recommissioned K13) and K14 collided although both survived. In just 75 minutes, two submarines had been sunk, three badly damaged and 105 crew killed.

- K5 was lost due to unknown reasons during a mock battle in the Bay of Biscay on 20 January 1921. Nothing further was heard of her following a signal that she was diving, but wreckage was recovered later that day. It was concluded that she exceeded her safe maximum depth.

- K15 sank at her mooring in Portsmouth on 25 June 1921. This was caused by hydraulic oil expanding in the hot weather and contracting overnight as the temperature dropped and the consequent loss of pressure causing diving vents to open. The boat flooded through open hatches as it submerged. Prior to this in May of that year the boat had survived shipping a sea into her funnel uptakes which had doused the furnaces and caused her to sink stern first to the bottom. In that case quick action on part of Captain and crew had prevented loss of life.

K16 and K12 were both trapped on the bottom of Gareloch; their crews were luckier than that of K13 in that after several hours submerged they managed to claw their way back to the surface.

K3 held the unofficial record for maximum diving depth (266 feet (81 m)) following an uncontrolled descent to the bottom of the Pentland Firth. The ship managed to surface without further difficulty despite spending an unrecorded period below 'crush depth.'

K4 ran aground on Walney Island in January 1917 and remained stranded there for some time.

Morale was a frequent problem. Submariners were 'Volunteers Only,' and the class reputation as being designated 'K' for Kalamity (or Killer) did little to endear them to their crews, or provide a steady stream of volunteers. Sailors serving aboard the boats blackly dubbed themselves the “Suicide Club.”[4]

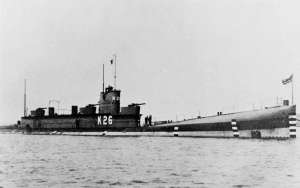

With a dive time of around 5 minutes (with the record being 3 minutes 25 seconds which was claimed by K8) it allowed the captain the luxury of being able to walk around the superstructure to ensure that the funnels were securely folded. The last, improved, boat, K26 was completed slowly, being commissioned in 1923. She had six 21-inch (530 mm) bow torpedo tubes but retained the 18-inch beam tubes. Her higher casing almost cured the problems of seawater entering the boiler room and improved ballast tank arrangements cut the diving time to 3 minutes 12 seconds to get to 80 feet (24 m). She also had an increased maximum diving depth of 250 feet (76 m).

Most were scrapped between 1921 and 1926 but K26 survived until 1931, being broken up because her displacement exceeded the limits for submarine displacement in the London Naval Treaty of 1930. K18, K19 and K20 became the new M-class submarines. K21, K23, K24, K25, K27 and K28 were cancelled. Although the concept of a submarine fast enough to operate with a battle fleet eventually fell out of favour, it was still an important consideration in the design of the River class in the late 1920s.

References

- ↑ Cocker, M. P.; Warne, Frederick (1982). Observer's Directory of Royal Naval Submarines 1901–1982. London. p. 42. ISBN 0723229643.

- ↑ A modern nuclear submarine has a reserve of around 13 percent

- ↑ Frick, Willis G. (1984). "Sink the Navy". Proceedings. United States Naval Institute. 110 (3): 173.

- ↑ Weintz, Steve (November 6, 2015). "His Majesty's Scary Steam Subs". http://www.WarIsBoring.com. Retrieved November 13, 2015. External link in

|website=(help)

Bibliography

- Brown, D.K. (2003). The Grand Fleet, Warship Design and Development 1906–1922. Caxton Editions. ISBN 1-84067-531-4.

- Cocker, M.P. (1982). Observer's Directory of Royal Naval Submarines 1901–1982, ISBN 0723229643, Frederick Warne, London.

- Everitt, Don. K Boats: Steam-Powered Submarines in World War I. Airlife Publishing. ISBN 1-84037-057-2.

- Everitt, Don (1963). The K Boats. London: George Harrap.

- Preston, Antony (2002). World's Worst Warships. Conway's Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-754-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to British K class submarines. |

- "Submarine losses 1904 to present day". RN Submarine museum.

- Steam Submarines

- 'K' for Katastrophe