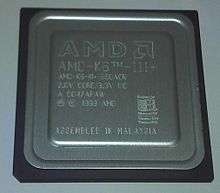

AMD K6-III

| |

| Produced | From February 1999 to 2000 |

|---|---|

| Common manufacturer(s) | |

| Max. CPU clock rate | 350 MHz to 550 MHz |

| FSB speeds | 66 MHz to 100 MHz |

| Min. feature size | 0.25µm to 0.18µm |

| Instruction set | MMX, 3DNow!, Enhanced 3DNow! (K6-III+) |

| Microarchitecture | x86 |

| Cores | 1 |

| Socket(s) | |

| Predecessor | K6-2 |

| Successor | K7 |

| Core name(s) |

|

The K6-III, code-named "Sharptooth", is an x86 microprocessor manufactured by AMD, released on 22 February 1999, with 400 and 450 MHz models. It was the last Socket 7 desktop processor. For an extremely short time after its release, the fastest available desktop processor from Intel was the Pentium II 450 MHz. However, the K6-III also competed against the Pentium III "Katmai" line, released just days later on February 26. "Katmai" CPUs reached speeds of 500 MHz, slightly faster than the K6-III 450 MHz. K6-III performance was significantly improved over the K6-2 due to the addition of an on-die L2 cache running at full clock speed. When equipped with a 1MB L3 cache on the motherboard the 400 and 450 MHz K6-IIIs is claimed by Ars Technica to often outperform[1] the hugely higher-priced Pentium III "Katmai" 450- and 500-MHz models, respectively.

Architecture

In conception, the design is simple: it was a K6-2 with on-die L2 cache. In execution, however, the design was not simple, with 21.4 million transistors. The pipeline was short compared to that of the Pentium III and thus the design did not scale well past 500 MHz. Nevertheless, the K6-III 400 sold well, and the AMD K6-III 450 was clearly the fastest x86 chip on the market on introduction, comfortably outperforming AMD K6-2s and Intel Pentium IIs.

3DNow!

3DNow! is an extension to the x86 instruction set developed by Advanced Micro Devices (AMD). It added single instruction multiple data (SIMD) instructions to the base x86 instruction set, enabling it to perform vector processing, which improves the performance of many graphic-intensive applications. The first microprocessor to implement 3DNow was the AMD K6-2, which was introduced in 1998.

The K6-III+ had the "Enhanced 3DNow!"(Extended 3DNow! or 3DNow+) which added 5 new DSP instructions, but not the 19 new extended MMX instructions.

TriLevel Cache

The original K6-2 had a 64 KB primary cache and a much larger amount of motherboard-mounted cache (usually 512 KB or 1024 KB but varying depending on the choice of motherboard). The K6-III, with its 256 KB on-die secondary cache, re-purposed the variable-size external cache on the motherboard as the L3 cache. This scheme was termed "TriLevel Cache" by AMD. The L3 cache has a capacity of up to 2 MB.

Market performance

Intel's Pentium II replacement was not yet available but, as a stop-gap, Intel introduced a modestly revised version of the Pentium II and re-badged it as the "Pentium III". The base design was unchanged (the addition of SSE instructions was at that time of no performance significance) but Intel's new production process allowed clockspeed improvements, and it became difficult to determine which company's part was the faster. Most industry observers regarded the Intel part as superior for floating-point intensive tasks (such as most 3D games), but the K6-III as better for mainstream integer work.

Both firms were keen to establish a clear lead, and both experienced manufacturing problems with their higher-frequency parts. AMD chose not to sell a 500 MHz or faster K6-III after the rare 500 MHz K6-III had been immediately recalled; it was found to be drawing enough current to damage some motherboards. AMD preferred to concentrate on their soon-to-be-released Athlon instead. Intel produced a 550 MHz Pentium III with some success but their 600 MHz version had reliability issues and was soon recalled.

With the release of the Athlon, the K6-III became something of an orphan. No longer a competitive CPU in its intended market segment, it nevertheless required substantial manufacturing resources to produce: in spite of its 21.4 million transistors, its 118 mm² die was considerably smaller than the 184 mm² of the 22-million-transistor Athlon (cache RAM taking much less area per-transistor than logic), but the K6-III was still significantly more costly to produce than the 81 mm² 9.3 million-transistor K6-2 CPUs. (roughly 2/3 the size of the K6-III) For a time, the K6-III was a low priority part for AMD—something to be made only when all orders for high-priced Athlons and cheap-to-produce K6-2s had been filled—and it became difficult to obtain in significant quantities.

The original K6-III went out of production when Intel released their "Coppermine" Pentium III (a much improved part that used an on-die cache) and, at the same time, switched to a new production process. The changeover was fraught with difficulties and Intel CPUs were in global short supply for 12 months or more. This, coupled with the better performance of the Athlon, resulted in even many former Intel-only manufacturers ordering Athlon parts, and stretched AMD's manufacturing facilities to the limit. In consequence, AMD stopped making the K6-III in order to leave more room to manufacture Athlons (and K6-2s).

K6-III+ and K6-2+

By the time the x86 CPU shortage was over, AMD had developed and released revised members of the K6 family. These K6-2+ and K6-III+ variants were specifically designed as low-power mobile (laptop) CPUs, and significantly marked the transition of the K6 architecture (and foretold of AMD's future K7 project) to the new 180 nm production process. Functionally, both parts were die shrunk K6-IIIs (the 2+ disabled 128 KiB of cache, the III+ had the full 256 KiB) and introduced AMD's new PowerNow! power saving technology. PowerNow! offered processor power savings for mobile applications by measuring computational load, and reduced processor operational voltage and frequency during idle periods in order to reduce overall system power consumption.

Although intended for notebook computers, both parts found an enthusiast following also in desktop systems as some motherboard companies (such as Gigabyte and FIC) provided BIOS updates for their desktop motherboards to allow usage of these processors. For other officially not supported mainboards, the enthusiast community created unofficial BIOS updates on their own.[2][3][4] These boards became firm favorites within the overclocking community. Both the K6-III+ and K6-2+ 450 MHz CPUs were routinely overclocked to over 600 MHz (112*5.5=616). Unfortunately, even with the 180 nm processshrink, the K6 architecture's short 6-stage pipeline while efficient, was difficult to scale with regards to clock speed. K6 III+ and 2+ were never offered higher than 570 MHz officially, and overclocking efforts using air cooling achieved a maximum around 800 MHz (133x6) at best - however this constraint was also exacerbated by a lack of Socket 7 motherboards supporting stable speeds over 112 MHz FSB.

As AMD's marketing resources at the time were focused on the launch of the upcoming Athlon K7 processor line, the 180 nm K6 series were relatively unknown outside of the industry.

Models

K6-III ("Sharptooth", K6-3D+, 250 nm)

- CPU ID: AuthenticAMD Family 5 Model 9

- L1-Cache: 32 + 32 KiB (Data + Instructions)

- L2-Cache: 256 KiB, fullspeed

- MMX, 3DNow!

- Socket 7, Super7

- Front side bus: 66/100, 100 MHz

- VCore: 2.2 V, 2.4 V

- First release: February 22, 1999

- Manufacturing process: 0.25 µm

- Clockrate: 400, 450 MHz

K6-III-P (250 nm, mobile)

- CPU ID: AuthenticAMD Family 5 Model 9

- L1-Cache: 32 + 32 KiB (Data + Instructions)

- L2-Cache: 256 KiB, fullspeed

- MMX, 3DNow!

- Socket 7, Super7

- Front side bus: 66, 95, 96.2, 66/100, 100 MHz

- VCore: 2.0 V, 2.2 V

- First release: May 31, 1999

- Manufacturing process: 0.25 µm

- Clockrate: 350, 366, 380, 400, 433, 450, 475 MHz

K6-2+ (180 nm, mobile)

- CPU ID: AuthenticAMD Family 5 Model 13

- L1-Cache: 32 + 32 KiB (Data + Instructions)

- L2-Cache: 128 KiB, fullspeed

- MMX, Extended 3DNow!, PowerNow!

- Super Socket 7

- Front side bus: 95, 97, 100 MHz

- VCore: 2.0 V

- First release: April 18, 2000

- Manufacturing process: 0.18 µm

- Clockrate: 450, 475, 500, 533, 550 MHz. (570 MHz, undocumented)

K6-III+ (180 nm, mobile)

- CPU ID: AuthenticAMD Family 5 Model 13

- L1-Cache: 32 + 32 KiB (Data + Instructions)

- L2-Cache: 256 KiB, fullspeed

- MMX, Extended 3DNow!, PowerNow!

- Super7

- Front side bus: 95, 100 MHz

- VCore: 2.0 V, (1.6 V, 1.8 V low voltage types)

- First release: April 18, 2000

- Manufacturing process: 0.18 µm

- Clockrate: 400, 450, 475, 500 MHz. (550 MHz, undocumented)

References

- ↑ Intel vs AMD, 1999

- ↑ M577 BIOS 03/06/1999 with K6-2+/III+ & HDD up to 128GB by Ondrej Zary on rainbow-software.org

- ↑ Award BIOS Modifications by Petr Soucek on ryston.cz

- ↑ K6plus by Jan Steunebrink on inter.nl.net

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to AMD K6-III. |

- AMD-K6-III Processor AMD (archived)

- AMD K6-III-P Mobile Product Brief AMD (archived)

- AMD K6-III+ Mobile Product Brief AMD (archived)

- Socket 7: Fit For Years To Come! at Tom's Hardware

- Recipe For Revival: K6-2+ at AcesHardware.Com (archived)

- K6-III+: Super-7 to the Limit at AcesHardware.Com (archived)