Kind Hearts and Coronets

| Kind Hearts and Coronets | |

|---|---|

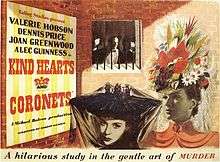

Original British film poster | |

| Directed by | Robert Hamer |

| Produced by |

Michael Balcon Michael Relph |

| Screenplay by |

Robert Hamer John Dighton |

| Based on |

Israel Rank: The Autobiography of a Criminal by Roy Horniman |

| Starring |

Dennis Price Valerie Hobson Joan Greenwood Alec Guinness |

| Music by | Ernest Irving |

| Cinematography | Douglas Slocombe |

| Edited by | Peter Tanner |

Production company | |

| Distributed by |

GFD (UK) Eagle-Lion Films (US) |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 106 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

Kind Hearts and Coronets is a British black comedy film of 1949 starring Dennis Price, Joan Greenwood, Valerie Hobson, and Alec Guinness, who famously plays eight distinct characters. The plot is loosely based on the novel Israel Rank: The Autobiography of a Criminal (1907) by Roy Horniman,[1] with the screenplay written by Robert Hamer and John Dighton and the film directed by Hamer. The title refers to a line in Tennyson's poem "Lady Clara Vere de Vere": "Kind hearts are more than coronets, and simple faith than Norman blood."[2]

Kind Hearts and Coronets is listed in Time's top 100[3] and also in the BFI Top 100 British films.[4] In 2011 the film was digitally restored and re-released in selected British cinemas.[5]

Plot

In Edwardian England, an imprisoned Louis D'Ascoyne Mazzini, 10th Duke of Chalfont (Dennis Price) awaits his hanging the following morning. As he writes his memoirs in his cell, the events of his life are shown in flashback.

His mother, the youngest daughter of the 7th Duke of Chalfont, fell in love with an Italian opera singer named Mazzini (also played by Price). After eloping with him, she was disowned by her aristocratic family for marrying beneath her station. Even so, the Mazzinis were poor but happy until Mazzini died upon seeing Louis, his newborn son, for the first time.

In the aftermath, Louis' widowed mother raised him on the history of her family and told him how, unlike other aristocratic titles, the Dukedom of Chalfont, can descend to and through female heirs. Meanwhile, Louis' only childhood friends were Sibella (Joan Greenwood) and her brother, a local doctor's children.

When Louis left school, his mother wrote to her kinsman Lord Ascoyne D'Ascoyne, a private banker, for assistance in launching her son's career and received a letter denying that she or Louis were members of the family. Louis was forced to work as an assistant in a draper's shop. When his mother died, her last request, to be interred in the D'Ascoyne vault at Chalfont Castle, went unfulfilled.

Sibella ridiculed Louis's marriage proposal. Instead, she married Lionel Holland (John Penrose), a former schoolmate with a rich father. Soon after, Louis quarreled with customer Ascoyne D'Ascoyne, the banker's only child, Ascoyne D'Ascoyne had Louis dismissed from his drapery job.

Seething with hatred, Louis resolved to kill Ascoyne D'Ascoyne and the other seven people (all played by Alec Guinness) ahead of him in succession to the Dukedom.

After arranging a fatal boating accident for Ascoyne D'Ascoyne and his mistress, Louis wrote a letter of condolence to his victim's father, Lord Ascoyne D'Ascoyne. Deeply touched, Lord Ascoyne decided to employ him as a clerk. Gradually becoming a man of means, Louis rented a bachelor flat in St James's for his continuing affair with Sibella.

Louis then targeted Henry D'Ascoyne, a keen amateur photographer. He also met and was charmed by Henry's wife, Edith (Valerie Hobson). After substituting petrol for paraffin in the lamp of Henry's darkroom, Louis attended Henry's funeral with Edith and viewed the remaining D'Ascoynes for the first time. Deeply impressed by Edith's composure during her grief, Louis secretly decided to make her his Duchess.

Offended by the boring eulogy given by the Reverend Lord Henry D'Ascoyne, Louis decided to kill him next. Posing as the Anglican Bishop of Matabeleland, Louis visited the clergyman's parish and poisoned his port.

From the window of his flat, Louis then used a bow and arrow to shoot down the balloon from which the suffragette Lady Agatha D'Ascoyne is dropping leaflets over London, remarking:

- "I shot an arrow into the air.

- She fell to earth in Berkeley Square"

(parodying Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's poem The Arrow and the Song).

Louis next sent General Lord Rufus D'Ascoyne a jar of caviar which contained a home-made bomb. Reminded instantly of his service in the Crimean War, the General gleefully opened the jar and died in the ensuing explosion.

Admiral Lord Horatio D'Ascoyne of the Royal Navy presented a difficulty, as he rarely set foot on land. But the Admiral conveniently insisted on going down with his ship after causing a collision at sea. This episode is loosely based on the death of Vice-Admiral Sir George Tryon in 1893.

After carefully considering his offer, Edith agreed to marry Louis. They notified Ethelred, the childless, widowed 8th Duke, who invited them to spend a few days at the family seat, Chalfont Castle. But Ethelred casually informed Louis that he intended to marry again and produce an heir. To forestall this, Louis staged a hunting "accident", but, before murdering the Duke, he revealed his motive.

Lord Ascoyne D'Ascoyne died from the shock of learning that he had become the 9th Duke, thus sparing Louis a murder he would have been reluctant to commit. Louis then became the 10th Duke and was warmly welcomed by his new tenants, but his triumph proved short lived. A Scotland Yard Detective arrived at Chalfont Castle and arrested him for murder.

Lionel had been found dead following Louis's rejection of his drunken plea for help to avoid bankruptcy. When Louis was charged for his murder, he elected to be tried by his peers in the House of Lords. During the trial, Louis and Edith were married. Sibella, having an inkling of Louis' crimes, falsely testified that Lionel was about to seek a divorce and name Louis as co-respondent. Ironically, his fellow Peers unanimously convicted Louis of the one murder he had never even contemplated.

Louis was visited in prison by Sibella, who observed that the discovery of Lionel's suicide note and the sudden death of Edith would free Louis and enable them to marry, a proposal to which he agreed.

Completing his memoirs as dawn breaks, Louis comments that no word of the suicide note has yet been heard and that he is now resigned to his fate. Moments later, the hangman arrives at his cell.

Moments before Louis' hanging, however, news of the discovery of the suicide note reaches the prison governor.

Outside the prison, Louis finds both Edith and Sibella waiting for him. As he ponders which of them to kill, Louis quotes from The Beggar's Opera:

- "How happy could I be with either,

- Were t'other dear charmer away!"

When a reporter approaches to tell him that Tit-Bits magazine wishes to publish his memoirs, Louis suddenly remembers that he left his detailed confession in his cell.

American version

To satisfy the Hays Office Production Code, the film was censored for the American market.[6] Ten seconds were added to the ending, showing Louis's memoirs being discovered before he can retrieve them. The dialogue between Louis and Sibella was altered to play down their adultery; derogatory lines aimed at the Reverend Henry D'Ascoyne were deleted; and in the nursery rhyme "Eeny, meeny, miny, moe", sailor replaced the word nigger (restored to the original dialogue, in the 2011 Criterion Collection DVD set). The American version is six minutes shorter than the British original.

Cast

- Dennis Price as Louis Mazzini and his father

- Alec Guinness as eight members of the D'Ascoyne family: Ethelred "the Duke", Lord Ascoyne "the Banker", Reverend Lord Henry "the Parson", General Lord Rufus "the General", Admiral Lord Horatio "the Admiral", Young Ascoyne, Young Henry and Lady Agatha D'Ascoyne. He also plays the seventh duke in brief flashback sequences to Mama's youth.

- Valerie Hobson as Edith

- Joan Greenwood as Sibella

- Audrey Fildes as Mama

- Miles Malleson as the Hangman

- Clive Morton as the Prison Governor

- John Penrose as Lionel

- Cecil Ramage as Crown Counsel

- Hugh Griffith as the Lord High Steward, who presides over Louis's trial

- John Salew as Mr Perkins

- Eric Messiter as Inspector Burgoyne, of Scotland Yard

- Lyn Evans as the Farmer

- Barbara Leake as the Schoolmistress

- Peggy Ann Clifford as Maud Redpole

- Anne Valery as the Girl in the Punt, Ascoyne D'Ascoyne's mistress

- Arthur Lowe as the Tit-Bits Reporter

Production

Guinness was originally offered only four D'Ascoyne parts, recollecting: "I read [the screenplay] on a beach in France, collapsed with laughter on the first page, and didn't even bother to get to the end of the script. I went straight back to the hotel and sent a telegram saying, 'Why four parts? Why not eight!?'"[7]

The exterior location used for Chalfont, the family home of the D'Ascoynes, is Leeds Castle in Kent.[8] The interior was filmed at Ealing Studios.

The village scenes were filmed in the Kent village of Harrietsham.[9]

In one of the most technically acclaimed shots in the film, Guinness appears as all his characters at once in a single frame. This was accomplished by masking the lens. The film was re-exposed several times with Guinness in different positions over several days. Douglas Slocombe, the cinematographer in charge of the effect, recalled sleeping in the studio to make sure nobody touched the camera.[10]

Reception

Bosley Crowther, critic for the New York Times, calls it a "delicious little satire on Edwardian manners and morals" in which "the sly and adroit Mr. Guinness plays eight Edwardian fuddy-duds with such devastating wit and variety that he naturally dominates the film."[11] Praise is also given to Price ("as able as Mr. Guinness in his single but most demanding role"), as well as Greenwood and Hobson ("provocative as women in his life").[11]

Roger Ebert lists Kind Hearts and Coronets among his "Great Movies",[12] stating "Price is impeccable as the murderer: Elegant, well-spoken, a student of demeanor", and notes that "murder, Louis demonstrates, ... can be most agreeably entertaining".[13]

Novel

Reviewer Simon Heffer notes the plot of the original Roy Horniman novel was darker (e.g., the murder of a child) and differed in several respects. A major difference was that the main character was the half-Jewish (as opposed to half-Italian) Israel Rank, and Heffer noted that "...his ruthless using of people (notably women) and his greedy pursuit of position all seem to conform to the stereotype that the anti-semite has of the Jew."[1]

Historical source

The death of Admiral Horatio D'Ascoyne was inspired by a true event: the collision between HMS Victoria and HMS Camperdown off Tripoli in 1893 because of an order given by Vice-Admiral Sir George Tryon. Sir George chose to go down with his ship, saying "It was all my fault."[14] The Victoria was sunk, losing over 300 men (including the admiral).

Radio adaptations

The film has been adapted for radio. In March 1965, the BBC Home Service broadcast an adaptation by Gilbert Travers-Thomas, with Dennis Price reprising his role as Louis D'Ascoyne Mazzini. in 1990, BBC Radio 4 produced a new adaptation featuring Robert Powell as the entire D'Ascoyne clan, including Louis, and Timothy Bateson as the hangman,[15] and another for BBC7 featuring Michael Kitchen as Mazzini and Harry Enfield as the D'Ascoyne family.

On 19 May 2012, BBC Radio 4 broadcast a sequel to the film called Kind Hearts and Coronets – Like Father, Like Daughter. In it, Unity Holland (played by Natalie Walter), the daughter of Louis and Sibella, is written out of the title by Lady Edith D'Ascoyne. Unity then murders the entire D'Ascoyne family, with all seven members played by Alistair McGowan.[16]

Broadway musical

In 2013, a musical version entitled A Gentleman's Guide to Love and Murder opened at the Walter Kerr Theater on Broadway to critical acclaim. The show has all the victims played by the same actor, in the original company Jefferson Mays. Though the plot remains essentially the same, most of the names are changed - half-Italian Louis Mazzini becomes half-Castilian Montague Navarro, the D'Ascoynes become the D'Ysquiths, and Henry's wife Edith becomes Henry's sister Phoebe. Although the musical was developed as a faithful adaptation of the film, a rights issue prompted the removal of any material originating in the film, and the musical is officially based on the same Roy Horniman novel the film takes its basis from. The musical won four Tony Awards, including Best Musical.

Digital restoration

The Criterion Collection released a two DVD disc set (Disc One: The Film, and Disc Two: The Supplements); Disc One featured the standard 'UK' version of the film, and as a bonus feature Disc One also included the final scene with the American ending. Disc Two includes a 75-minutes BBC TV Omnibus documentary "Made in Ealing", plus a 68-minute talk-show appearance with Alec Guinness on the BBC TV Parkinson Show.[17] UK distributor Optimum Releasing released a digitally restored version for both DVD and Blu-ray on 5 September 2011.[18]

Notes

References

- 1 2 Simon Heffer (December 2008). "Israel Rank Reviewed". UK: Faber.

- ↑ "The early poems", Tennyson, Online Literature.

- ↑ Time, 12 February 2005.

- ↑ BFI, UK.

- ↑ Words from the wise, Empire online.

- ↑ Slide, Anthony (1998). Banned in the USA: British Films in the United States and Their Censorship, 1933–1966. IB Tauris. p. 90. ISBN 1-86064-254-3. Retrieved 2 October 2008.

- ↑ Raoul Hernandez (24 February 2006). "Kind Hearts and Coronets". The Austin Chronicle.

- ↑ "Kind Hearts and Coronets". Movie locations.

- ↑ Kent Film Office. "Kent Film Office Kind Hearts and Coronets Film Focus".

- ↑ David A. Ellis (2012). Conversations with Cinematographers. Scarecrow Press. pp. 13–29. ISBN 978-0-8108-8126-6.

- 1 2 Bosley Crowther (15 June 1950). "Alec Guinness Plays 8 Roles in 'Kind Hearts and Coronets,' at Trans-Lux 60th Street at the Cinemet". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- ↑ Roger Ebert. "great movies". rogerebert.com. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- ↑ Roger Ebert (15 September 2002). "Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949)". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- ↑ Jasper Copping (12 January 2012). "Explorers raise hope of Nelson 'treasure trove' on Victorian shipwreck". The Telegraph. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- ↑ Programmes, UK: BBC.

- ↑ "Saturday Drama: Kind Hearts and Coronets – Like Father, Like Daughter". BBC. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- ↑ Kind Hearts & Coronets, Criterion.

- ↑ "Kind Hearts and Coronets DVD and Blu-ray releases". My Reviewer.

Bibliography

- Horniman, Roy (1907), Israel Rank: The Autobiography of a Criminal, London: Chatto & Windus, OCLC 818824203.

- Vermilye, Jerry (1978), The Great British Films, Citadel Press, pp. 131–33, ISBN 0-8065-0661-X.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Kind Hearts and Coronets |

- Kind Hearts and Coronets at the Internet Movie Database

- Kind Hearts and Coronets at AllMovie

- Essay at The Criterion Collection: Kind Hearts and Coronets – Ealing’s Shadow Side Linked 2013-05-12

- The Daily Telegraph, 9 July 2009: Kind Hearts and Coronets: 60th anniversary of a classic Linked 2013-05-12

- Virtual History: Books on Kind Hearts and Coronets Linked 2013-05-12