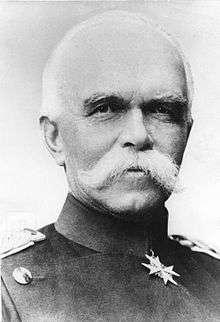

Leo von Caprivi

| Leo von Caprivi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chancellor of Germany | |

|

In office 20 March 1890 – 26 October 1894 | |

| Monarch | Wilhelm II |

| Deputy | Karl Heinrich von Boetticher |

| Preceded by | Otto von Bismarck |

| Succeeded by | Chlodwig von Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst |

| Prime Minister of Prussia | |

|

In office 20 March 1890 – 22 March 1892 | |

| Monarch | Wilhelm II |

| Preceded by | Otto von Bismarck |

| Succeeded by | Botho zu Eulenburg |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Georg Leo von Caprivi 24 February 1831 Berlin, Prussia (Now Germany) |

| Died |

6 February 1899 (aged 67) Skyren, Germany (Now Skórzyn, Poland) |

| Political party | Independent |

| Religion | Lutheran |

| Awards | Pour le Mérite |

| Signature |

|

| Military service | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Years of service | 1849–1888 |

| Rank |

General der Infanterie Vize Admiral |

| Battles/wars |

Second Schleswig War Austro-Prussian War |

Georg Leo Graf von Caprivi de Caprera de Montecuccoli (English: Count George Leo of Caprivi, Caprera, and Montecuccoli, born Georg Leo von Caprivi; 24 February 1831 – 6 February 1899) was a German general and statesman who succeeded Otto von Bismarck as Chancellor of Germany. Caprivi served as German Chancellor from March 1890 to October 1894. Caprivi promoted industrial and commercial development, and concluded numerous bilateral treaties for reduction of tariff barriers. However, this movement toward free trade angered the conservative agrarian interests, especially the Junkers. He promised the Catholic Center party educational reforms that would increase their influence, but failed to deliver. As part of Kaiser Wilhelm's "new course" in foreign policy, Caprivi abandoned Bismarck's military, economic, and ideological cooperation with Russia, and was unable to forge a close relationship with Britain. He successfully promoted the reorganization of the German military.[1]

Biography

Leo von Caprivi was born in Charlottenburg (then a town in the Prussian Province of Brandenburg, today a district of Berlin) the son of jurist Julius Leopold von Caprivi (1797–1865), who later became a judge at the Prussian supreme court and member of the Prussian House of Lords. His father's family was of Italian and possibly Slovene origin; it has been claimed that their original surname was Kopriva and they originated from Koprivnik (Nesseltal) near Kočevje in the Kočevje Rog (Hornwald) region of Lower Carniola (present-day Slovenia).[2][3][4] However, other research states that this cannot be confirmed.[5] The Caprivis were ennobled during the 17th century Ottoman–Habsburg wars, they later moved to Landau in Silesia. His mother was Emilie Köpke, daughter of Gustav Köpke, headmaster of the Berlinisches Gymnasium zum Grauen Kloster and teacher of Caprivi's predecessor Otto von Bismarck.

Military career

Caprivi entered the Prussian Army in 1849 and served in the Second Schleswig War of 1864, the Austro-Prussian War of 1866 as a major in the staff of Prince Friedrich Karl of Prussia, and the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71, the latter as Chief of Staff of the X Army Corps.[6] Backed by the Chief of the general staff Helmuth von Moltke, Caprivi achieved the rank of Lieutenant Colonel and distinguished himself at the Battle of Mars-la-Tour, the Siege of Metz and the Battle of Beaune-la-Rolande, receiving the military order Pour le Mérite.

After the war he served at the Prussian War Ministry. In 1882, he became commander of the 30th Infantry Division at Metz.[6] In 1883, he succeeded Albrecht von Stosch, a fierce opponent of Chancellor Bismarck, as Chief of the Imperial Navy. The appointment was made by Bismarck and caused great dissatisfaction among the officers of the navy. However, Caprivi showed significant administrative talent in the position.[6]

Caprivi's dissents with the naval policy of Emperor Wilhelm II led to his resignation in 1888. He was briefly appointed to the command of his old army corps, the X Army Corps stationed in Hanover, before being summoned to Berlin by Emperor Wilhelm II in February 1890. Caprivi was informed that he was the Kaiser's intended choice if Bismarck was resistant to Wilhelm's proposed changes to the government, and upon Bismarck's dismissal on 18 March, Caprivi became Chancellor.

Chancellor of Germany

| Office | Incumbent | In office | Party |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chancellor | Leo von Caprivi | 20 March 1890 – 26 October 1894 | None |

| Vice-Chancellor of Germany Secretary for the Interior |

Karl von Boetticher | 20 March 1890 – 26 October 1894 | None |

| Secretary for the Foreign Affairs | Herbert von Bismarck | 20 March 1890 – 26 March 1890 | None |

| Adolf von Bieberstein | 26 March 1890 – 26 October 1894 | None | |

| Secretary for the Treasury | Helmuth von Maltzahn | 20 March 1890 – 26 October 1894 | None |

| Secretary for the Justice | Otto von Oehlschläger | 20 March 1890 – 2 February 1891 | None |

| Robert Bosse | 2 February 1891 – 2 March 1892 | None | |

| Eduard Hanauer | 2 March 1892 – 10 July 1893 | None | |

| Rudolf Arnold Nieberding | 10 July 1893 – 26 October 1894 | None | |

| Secretary for the Navy | Karl Eduard Heusner | 26 March 1890 – 22 April 1890 | None |

| Friedrich von Hollmann | 22 April 1890 – 26 October 1894 | None | |

| Secretary for the Post | Heinrich von Stephan | 20 March 1890 – 26 October 1894 | None |

Caprivi's administration was marked by what is known to historians as the Neuer Kurs ("New Course")[7] in both foreign and domestic policy, with moves towards conciliation of the Social Democrats on the domestic front, and towards a pro-British foreign policy, exemplified by the Anglo-German Agreement of July 1890, in which the British ceded the island of Heligoland to Germany in exchange for control of Zanzibar. This led to animosity from the colonialist pressure-groups like the Alldeutscher Verband, while Caprivi's free trading policies led to opposition from conservative agrarian protectionists. The treaty also gave Germany the Caprivi Strip, which was added to German South-West Africa, thus linking that territory with the Zambezi River, which he had hoped to use for trade and communications with eastern Africa (the river proved to be unnavigable). He opposed the ideas of a preventive war against Russia developed by General Alfred von Waldersee, nevertheless he conformed to the decision of Emperor Wilhelm and the like-minded officials of the Foreign Office around Friedrich von Holstein not to renew the Reinsurance Treaty, whereafter Russia forged the Alliance with France.[8]

The rejection by the Conservatives intensified, accompanied with constant public attacks by retired Bismarck. Caprivi also lost the support of the National Liberals and Progressives in a legislative defeat of 1892 on an educational bill providing denominational board schools, a failed attempt to re-integrate the Catholic Centre Party after the Kulturkampf. Caprivi, although himself a Protestant, needed the 100 votes of the Catholic Centre Party but that alarmed the Protestant politicians.[9] Caprivi had to resign as Prussian Minister President and was replaced by Count Botho zu Eulenburg, leading to an untenable division of powers between the Chancellor and the Prussian premier, ultimately leading to the dismissal of both in 1894 and their succession by Prince Chlodwig von Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst.

A number of progressive reforms were carried out during Caprivi's time as Chancellor. The employment of children under the age of 13 was forbidden and 13- to 18-year-olds restricted to a maximum 10-hour day, in 1891 Sunday working was forbidden and a guaranteed minimum wage introduced, and working hours for women were reduced to a maximum of 11. Industrial tribunals were established in 1890 to arbitrate in industrial disputes, and Caprivi invited representatives of trade unions to sit on these tribunals. In addition, duties on imported timber, cattle, rye, and wheat were lowered and a finance bill introduced progressive income tax under which the more one earned, the more tax that person paid.[10] Other achievements included the army bills of 1892 and 1893, and the commercial treaty with Russia in 1894.[6]

Notes and references

- ↑ John C. G. Röhl (1967). Germany Without Bismarck: The Crisis of Government in the Second Reich, 1890-1900. University of California Press. pp. 77–90.

- ↑ "Rodbina † grofa Caprivija." 1899. Slovenec: političen list za slovenski narod 27(31) (8 Feb.): 4. (Slovene)

- ↑ "Ministri slovenskega rodu, a nemškega mišljenja." 1918. Tedenske slike 5(14): 154. (Slovene)

- ↑ Žužek, Aleš. 2013. "Nemški kancler, ki je bil slovenske gore list." SIOL (8 Dec.). (Slovene)

- ↑ Petschauer, Erich. 1984. "Das Jahrhundertbuch": Gottschee and Its People Through the Centuries. New York: Gottscheer Relief Association, p. 205.

- 1 2 3 4

Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). "Caprivi, Georg Leo, Graf von". Encyclopedia Americana.

Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). "Caprivi, Georg Leo, Graf von". Encyclopedia Americana. - ↑ Calleo, D. (1980). The German Problem Reconsidered:Germany and the World Order 1870 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 19. ISBN 9780521299664. Retrieved 2015-02-27.

- ↑ Raymond James Sontag, Germany and England: Background of Conflict, 1848–1894 (1938) ch 9

- ↑ John C. G. Röhl (1967). Germany Without Bismarck: The Crisis of Government in the Second Reich, 1890-1900. pp. 77–90.

- ↑ AQA History: The Development of Germany, 1871–1925 by Sally Waller

Further reading

- Röhl, John C. G. (1967). Germany Without Bismarck: The Crisis of Government in the Second Reich, 1890-1900. University of California Press. pp 56–117

- Sempell, Charlotte. "The Constitutional and Political Problems of the Second Chancellor, Leo Von Caprivi," Journal of Modern History, (September 1953) 25#3 pp 234–254, in JSTOR

- Sontag, Raymond James. Germany and England: Background of Conflict, 1848–1894 (1938) ch 9

- Die Reden des Grafen von Caprivi im deutschen Reichstage, preussischen Landtage und besondern Anlässen "The Speeches of Count von Caprivi in the German Reichstag, in the Prussian Landtag, and on special occasions" in German (Google Book)

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Otto von Bismarck |

Prime Minister of Prussia 1890–1892 |

Succeeded by Count Eulenburg |

| Chancellor of Germany 1890–1894 |

Succeeded by Prince Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst | |

.jpg)