Leonard D. Abbott

Leonard Dalton Abbott (1878–1953) was an English-born American publicist, politician, and freethinker. Originally a socialist, Abbott turned to anarchism and remained a Georgist later in life. He is best remembered as a leader of the so-called "Modern School movement" of those years.

Biography

Early years

Leonard D. Abbott was born in Liverpool, Lancashire, England on May 20, 1878. Leonard's father, Lewis Lowe Abbott, was a prosperous New England metal merchant of Anglo-Saxon ethnic stock and a graduate of Yale College. In January 1876, the elder Abbott took a position with the firm of Dickerson & Co.[1] and on behalf of that firm spent the next two decades in Liverpool representing the commercial interests of American firms abroad.[2] It was owing to this employment situation that Leonard, the child of American parents, was born abroad. Abbott's siblings included Clinton Gilbert Abbott (1881–1946), who became director of the San Diego Natural History Museum.

Leonard came to the United States for the first time in 1897, settling in New York City. Under the influence of the British socialist-turned-anarchist William Morris,[3] Abbott engrossed himself in the socialist movement, in which he remained an active worker up to 1905.

Shortly after his arrival in America, Abbott became the art editor for The Literary Digest, one of the leading news weeklies of the period.[4] Abbott also reported on the American socialist movement to the British Labour Annual each year from 1899 to 1901.[3]

Abbott was a leading figure in the Social Democratic Party of America (SDP), an organization based in Chicago and headed by journalist Victor L. Berger and union activist Eugene V. Debs. He was a keynote speaker at a June 1900 convention which united the forces of the Chicago SDP and an organization formerly hailing from the Socialist Labor Party of America behind the Presidential candidacy of Eugene Debs and Benjamin Hanford.[4] Abbott was named a candidate of the combined Social Democratic Party for New York State Treasurer by that same gathering.[5]

In 1901, Abbott became one of seven members of the editorial board of a new illustrated socialist magazine published in New York City, The Comrade. In its inaugural issue, the editors of the monthly declared their intention was not to deal with the economic factor of the socialist movement, but rather with "such literary and artistic productions as reflect the soundness of the Socialist philosophy."[6] The new century was seen by the editors as marking the dawn of a new era of artistic creation:

"The fires on the old altars are dead. The religion of today is impotent; the Art of today is parasitic; the life of today is stifled. Into this miasma of commercialism is coming the breath of a new ideal. Men are growing conscious of the fact that present social forms are passing. They are beginning to understand that they can take hold of the world and fashion it anew after their desires, and it is in this instinct of creation that they become likest unto gods. The sensitive soul of the poet and the artist is quickest to respond to this instinct, and everywhere the artistic sense is finding expression in Socialist terms."[6]

In conjunction with his role as a member of the editorial board of The Comrade, Abbott became a frequent contributor of biographical sketches on such worthies as the socialist novelist Edward Carpenter, poet Edward Markham, and painters Vasily Vereshchagin and Jean-François Millet. The publication survived until 1905, at which time it was dissolved and its subscription list taken over by The International Socialist Review of Chicago.

In addition to his writing for The Comrade, Abbott sat on the editorial board of the Chicago publication Socialist Spirit from 1900 to 1903 and edited The Free Comrade with J.W. Lloyd from 1900 to 1902.[3] Abbott was also an associate editor of Current Literature for over a quarter century.[3]

Pedagogical work

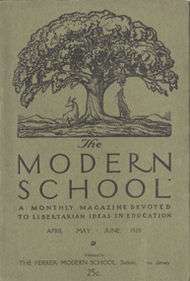

After about 1905, Abbott's interests turned to libertarian education, in which he at once assumed a commanding presence. He was associated in the publication of The Commonwealth, Current Opinion, and The Modern School.

Abbott sat on the first executive board of the Rand School of Social Science, started through the volition of his friends George D. Herron and Carrie Rand Herron. He was also influential in the establishment of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society, and the Ferrer School of Stelton, New Jersey.

Abbott was influential in the foundation in New York City in 1911 of what was to become the Stelton Modern School, together with other leading anarchists such as Alexander Berkman, Voltairine de Cleyre, and Emma Goldman. Commonly called the "Ferrer Center," the facility was established just two years after the execution for sedition of Francisco Ferrer. The Ferrer Center first held meetings on St. Mark's Place, in Manhattan’s Lower East Side, but twice moved elsewhere, first within lower Manhattan, then to Harlem.

Starting in 1912, the school’s principal was the philosopher Will Durant, who also taught there. Besides Berkman and Goldman, the Ferrer Center faculty included the Ashcan School painters Robert Henri and George Bellows, and its guest lecturers included writers and political activists such as Margaret Sanger, Jack London, and Upton Sinclair.[7] Student Magda Schoenwetter recalled that the school used Montessori methods and equipment, and emphasised academic freedom rather than fixed subjects, such as spelling and arithmetic.[8]

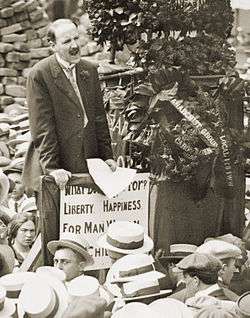

Abbott was a public proponent of free speech and pacifism and served for a time as president of the Free Speech League. In this capacity he became involved in a free speech fight in Tarrytown, New York by the Industrial Workers of the World in 1914 over a ban on outdoor public meetings enacted by that community.[9] Not accidentally, Tarrytown was the location of the estate of industrialist John D. Rockefeller.

In July 1914, radical anarchists who frequented the Ferrer Center, and loosely associated with its adult education program, plotted to bomb the mansion of Standard Oil chairman Rockefeller. On failing to enter the Rockefeller estate in Tarrytown. The group took the bomb back to the Lexington Avenue apartment of Louise Berger (a school habitué and an editor of the Mother Earth Bulletin), where it exploded, killing four people, including three of the bombers, and wounding many others. The Ferrer Center became politically notorious and was shortly compelled to leave New York City for the comparative isolation of Stelton, New Jersey. Abbott was among those who addressed a mass meeting attended by 5,000 in remembrance of those killed in the explosion.[10]

Death and legacy

Leonard D. Abbott died in 1953.

Footnotes

- ↑ Record of Class Meetings and the Biographical History of the Class of 1866, Yale College. Hartford, CT: Press of the Case, Lockwood, and Brainard Co., 1891; pg. 10.

- ↑ Paul Avrich, The Modern School Movement: Anarchism and Education in the United States. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1980; pg. 183.

- 1 2 3 4 Candace Falk with Barry Pateman and Jessica Moran (eds.), Emma Goldman: A Documentary History of the American Years: Volume 2: Making Speech Free, 1902-1909. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005; pg. 507.

- 1 2 Howard H. Quint, The Forging of American Socialism: Origins of the Modern Movement. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1953; pg. 353.

- ↑ "Social Democrats' Ticket," New York Times, June 17, 1900.

- 1 2 "Greeting," The Comrade (New York), vol. 1, no. 1 (October 1901), pg. 12.

- ↑ Avrich, Paul, The Modern School Movement. Oakland: AK Press, 2005; pg. 212.

- ↑ Paul Avrich, Anarchist Voices: An Oral History of Anarchism in America. Oakland: AK Press, 2005; pg. 230.

- ↑ "Direct Action: Leonard Abbott Would Now Defy Authorities in Tarrytown," New York Times, June 25, 1914.

- ↑ "5000 at Memorial to Anarchist Dead," New York Times, July 12, 1914.

Works

- The Society of the Future. Girard, KS: J.A. Wayland, 1898. —Part of the series "One Hoss Philosophy," no. 7.

- "William Morris's Commonweal," The New England Magazine, vol. 20, no. 4 (June 1899), pp. 428–433.

- "A Latter-Day Brook Farm," International Socialist Review, vol. 1, no. 11 (May 1901), pp. 700–703.

- "The Poetry of Edward Carpenter," The Comrade (New York), vol. 1, no. 2 (November 1901), pp. 39–40.

- A Socialistic Wedding: Being the Account of the Marriage of George D. Herron and Carrie Rand. New York: Knickerbocker Press, 1901.

- "Edwin Markham: Laureate of Labor," The Comrade (New York), vol. 1, no. 4 (January 1902), pp. 74–75.

- "Verestchagin, Painter of War," The Comrade (New York), vol. 1, no. 7 (April 1902), pp. 155–156.

- "In Memoriam: Émile Zola," The Comrade (New York), vol. 2, no. 2 (November 1902), pg. 26.

- "A Tribute to Elizabeth Cady Stanton," The Comrade (New York), vol. 2, no. 3 (December 1902), pg. 58.

- "Millet: The Painter of the Common Life," The Comrade (New York), vol. 2, no. 7 (April 1903), pp. 149–151.

- "The Influence of Emerson and Thoreau," The Comrade (New York), vol. 2, no. 10 (July 1903), pp. 222–224.

- The Root of the Social Problem. Published with Owen Lovejoy's "Prepare of Campaign of 1904." New York: Socialistic Co-operative Publishing Association, 1903.

- Ernest Howard Crosby: A Valuation and a Tribute. Westwood, MA: Ariel Press, 1907.

- Sociology and Political Economy. New York: Current Literature, 1909.

- Francisco Ferrer: His Life, Work, and Martyrdom. New York: Francisco Ferrer Association, 1910.

- "A History of the Ferrer Association," in Bayard Boyesen, The Modern School in New York. New York: Francisco Ferrer Association, 1911.

- International Anarchist Manifesto on the War. London: n.p., 1915.

Further reading

- Paul Avrich, The Modern School Movement: Anarchism and Education in the United States. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1980.

See also

External links

- Finding Aid for the Modern School Collection, Special Collections and University Archives, Rutgers University Libraries, New Brunswick, New Jersey. Retrieved August 1, 2010.

- The Stelton Modern School: The History, Talking History.org, March–May 2001. Retrieved August 1, 2010.