Lip plate

| Lip plate | |

|---|---|

|

Contemporary Mursi woman showing pierced lower lip without a lip plate | |

| Nicknames | Labret, lip plate, lip disc |

| Location | Omo River, Ethiopia |

| Jewelry | Clay or wood disc |

The lip plate, also known as a lip plug or lip disc, is a form of body modification. Increasingly large discs (usually circular, and made from clay or wood) are inserted into a pierced hole in either the upper or lower lip, or both, thereby stretching it. The term labret denotes all kinds of pierced-lip ornaments, including plates and plugs.

Archaeological evidence indicates that labrets have been independently invented no fewer than six times, in Sudan and Ethiopia (8700 BC), Mesoamerica (1500 BC), and Coastal Ecuador (500 BC).[1] Today, the custom is maintained by a few groups in Africa and Amazonia.

Usage in Ethiopia

In Africa, a lower lip plate is usually combined with the excision of the two lower front teeth, sometimes all four. Among the Sara people and Lobi of Chad, a plate is also inserted into the upper lip. Other tribes, such as the Makonde of Tanzania and Mozambique, used to wear a plate in the upper lip only. Many older sources reported that the plate's size was a sign of social or economical importance in some tribes. But, because of natural mechanical attributes of human skin, the plate's size may often depend on the stage of stretching of the lip and the wishes of the wearer.

Among the Surma (own name Suri) and Mursi people of the lower Omo River valley in Ethiopia,[2] about 6 to 12 months before marriage, a young woman has her lip pierced by her mother or one of her kinswomen, usually at around the age of 15 to 18. The initial piercing is done as an incision of the lower lip of 1 to 2 cm length, and a simple wooden peg is inserted. After the wound has healed, which usually takes between two and three weeks, the peg is replaced with a slightly bigger one. At a diameter of about 4 cm, the first lip plate made of clay is inserted. Every woman crafts her own plate and takes pride in including some ornamentation. The final diameter ranges from about 8 cm to over 20 cm.[3]

In 1990 Beckwith and Carter claimed that for Mursi and Surma women, the size of their lip plate indicates the number of cattle paid as the bride price.[4] Whereas anthropologist Turton, who studied the Mursi for 30 years, denies this.[5] Shauna LaTosky, building from field research among the Mursi in 2004, discusses in detail why most Mursi women use lip plates and describes the value of the ornamentation within a discourse of female strength and self-esteem.[6]

In contemporary culture, most girls of age 13 to 18 appear to decide whether or not to wear a lip plate. This adornment has attracted tourists to view the Mursi and Surma women, with mixed consequences for these tribes.[7]

The largest lip plate recorded was in Ethiopia, measuring 59.5 cm (23.4 in) in circumference and 19.5 cm (7.6 in) wide, in 2014.[8]

Usage in the Americas

In South America among some Amazonian tribes, young males traditionally have their lips pierced and begin to wear plates when they enter the men's house and leave the world of women.[9][10] Lip plates there are associated with oratory and singing. The largest plates are worn by the greatest orators and war chiefs, such as Chief Raoni of the Kayapo tribe, a well known environmental campaigner. In South America, lip plates are nearly always made from light wood.

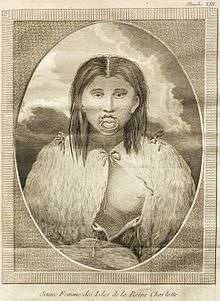

In the Pacific Northwest of North America, among the Haida, Tsimshian, and Tlingit, lip plates are used by women to symbolize social maturity by indicating a girl's eligibility to be a wife. The installation of a girl's first plate was celebrated with a sumptuous feast.[11]

In western nations, some young people, including some members of the Modern Primitive movement, have adopted larger-gauge lip piercings, a few large enough for them to wear proper lip plates. Some examples are given on the BME website.[12][13][14]

List of traditional wearers

Tribes that are known for their traditional lip plates include:

- The Mursi and Surma (Suri) women of Ethiopia

- The Sara women of Chad (ceased wearing plates in the 1920s)

- The Makonde of Tanzania and Mozambique (ceased wearing plates several decades ago)

- The Suyá men of Brazil (most no longer wear plates)

- The Botocudo of coastal Brazil (in previous centuries, both sexes wore plates)

- Aleut, Inuit and other indigenous peoples of northern Canada, Alaska and surrounding regions also wore large labrets and lip plates; these practices had mostly ceased by the twentieth century.

- Some tribes (Zo'e in Brazil, Nuba in Sudan, Lobi in west Africa) wear stretched-lip ornaments that are plug- or rod-shaped rather than plate-shaped.

Ubangi misnomer

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, African women wearing lip plates were brought to Europe and North America for exhibit in circuses and sideshows. Around 1930, Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey promoted such women from the French Congo as members of the "Ubangi" tribe; the Ringling press agent admitted that he picked that name from a map for its exotic sound.[15] The word Ubangi was still given a definition as an African tribe in 2009 in some English-language dictionaries.[16] The word was used in this way in the 1937 Marx Brothers film A Day at the Races.

References

- ↑ Grant Keddie: "Symbolism and Context: world history of the labret". Circum-Pacific Prehistory Conference. Seattle, 1989

- ↑ Mursi Online, David Turton's site

- ↑ Beckwith, Carol; Fisher, Angela (1996). "The eloquent Surma". National Geographic (The young woman pictured on page 89 is wearing a 21–22 cm plate.) (179.2): 77‒99.

- ↑ Beckwith, Carol; Carter, Angela (1990). African Ark. Collins Harvill. p. 251. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "Mursi Lip-plates (dhebi a tugoin)". Mursi Online.

- ↑ LaTosky, Shauna (2006). Strecker, Ivo; Lydall, Jean, eds. "Reflections on the lip-plates of Mursi women as a source of stigma and self-esteem" (PDF). Perils of Face: Essays on Cultural Contact, Respect and Self-esteem in Southern Ethiopia. Berlin: Lit Verlag: 382‒397.

- ↑ Turton, David (2004). "Lip-plates and 'the people who take photographs: uneasy encounters between Mursi and tourists in southern Ethiopia" (PDF). Anthropology Today. pp. 3–8.

- ↑ Glenday, Craig (2015). Guinness Book of World Records 2016. p. 60. ISBN 9781910561010.

- ↑ Archived 18 February 2005 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Anthony Seeger: "The meaning of body ornaments: a Suya example," Ethnology 14(3) pp 211-224, 1975.

- ↑ Aldona Jonaitis: "Women, Marriage, Mouths and Feasting: The Symbolism of Tlingit Labrets", pp 191-205 of Arnold Rubin (ed): Marks of Civilization, Museum of Cultural History, UCLA, 1988

- ↑ Interviews with two plate-wearers

- ↑ Photos of modern scalpelled and other large-gauge lip piercings

- ↑ Photos of small lip plates Archived 15 July 2006 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Joe Nickell: Secrets of the Sideshows, page 189. The University Press of Kentucky. 2005.

- ↑ "Ubangi." Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House, Inc. 11 Nov. 2009. Merriam-Webster Online. 11 November 2009.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Labret. |

- YouTube video showing Sara Kaba women with the double lip plates they used to wear

- flickr: Surma and Mursi maxi-lips

- Plughog.com: Lip Stretching Guide

- Youtube video showing Sara women