Liver transplantation

| Liver transplantation | |

|---|---|

| Intervention | |

Human liver | |

| ICD-9-CM | 50.5 |

| MeSH | D016031 |

| MedlinePlus | 003006 |

Liver transplantation or hepatic transplantation is the replacement of a diseased liver with some or all of a healthy liver from another person (allograft). The most commonly used technique is orthotopic transplantation, in which the native liver is removed and replaced by the donor organ in the same anatomic location as the original liver. Liver transplantation is a viable treatment option for end-stage liver disease and acute liver failure. Typically three surgeons and two anesthesiologists are involved, with up to four supporting nurses. The surgical procedure is very demanding and ranges from 4 to 18 hours depending on outcome. Numerous anastomoses and sutures, and many disconnections and reconnections of abdominal and liver tissue, must be made for the transplant to succeed, requiring an eligible recipient and a well-calibrated live or cadaveric donor match.

History

The first human liver transplant was performed in 1963 by a surgical team led by Dr. Thomas Starzl of Denver, Colorado, United States.[1] Dr. Starzl performed several additional transplants over the next few years before the first short-term success was achieved in 1967 with the first one-year survival post transplantation. Despite the development of viable surgical techniques, liver transplantation remained experimental through the 1970s, with one year patient survival in the vicinity of 25%. The introduction of ciclosporin by Sir Roy Calne, Professor of Surgery Cambridge, markedly improved patient outcomes, and the 1980s saw recognition of liver transplantation as a standard clinical treatment for both adult and pediatric patients with appropriate indications. Liver transplantation is now performed at over one hundred centers in the US, as well as numerous centres in Europe and elsewhere. One-year patient survival is 80–85%, and outcomes continue to improve, although liver transplantation remains a formidable procedure with frequent complications. The supply of liver allografts from non-living donors is far short of the number of potential recipients, a reality that has spurred the development of living donor liver transplantation. The first altruistic living liver donation in Britain was performed in December 2012 in St James University Hospital Leeds. First transplant in Pakistan was performed in 2011 (This transplant is momentous as it was done with help from doctors from India).

Indications

Liver transplantation is potentially applicable to any acute or chronic condition resulting in irreversible liver dysfunction, provided that the recipient does not have other conditions that will preclude a successful transplant. Uncontrolled metastatic cancer outside liver, active drug or alcohol abuse and active septic infections are absolute contraindications. While HIV infection was once considered an absolute contraindication, this has been changing recently. Advanced age and serious heart, lung, or other disease may also prevent transplantation (relative contraindications). Most liver transplants are performed for chronic liver diseases that lead to irreversible scarring of the liver, or cirrhosis of the liver. Some centers use the Milan criteria to select patients with liver cancers for liver transplantation.

Techniques

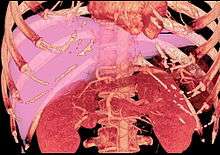

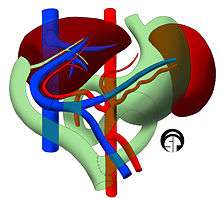

Before transplantation, liver-support therapy might be indicated (bridging-to-transplantation). Artificial liver support like liver dialysis or bioartificial liver support concepts are currently under preclinical and clinical evaluation. Virtually all liver transplants are done in an orthotopic fashion, that is, the native liver is removed and the new liver is placed in the same anatomic location.[1] The transplant operation can be conceptualized as consisting of the hepatectomy (liver removal) phase, the anhepatic (no liver) phase, and the postimplantation phase. The operation is done through a large incision in the upper abdomen. The hepatectomy involves division of all ligamentous attachments to the liver, as well as the common bile duct, hepatic artery, hepatic vein and portal vein. Usually, the retrohepatic portion of the inferior vena cava is removed along with the liver, although an alternative technique preserves the recipient's vena cava ("piggyback" technique).

The donor's blood in the liver will be replaced by an ice-cold organ storage solution, such as UW (Viaspan) or HTK until the allograft liver is implanted. Implantation involves anastomoses (connections) of the inferior vena cava, portal vein, and hepatic artery. After blood flow is restored to the new liver, the biliary (bile duct) anastomosis is constructed, either to the recipient's own bile duct or to the small intestine. The surgery usually takes between five and six hours, but may be longer or shorter due to the difficulty of the operation and the experience of the surgeon.

The large majority of liver transplants use the entire liver from a non-living donor for the transplant, particularly for adult recipients. A major advance in pediatric liver transplantation was the development of reduced size liver transplantation, in which a portion of an adult liver is used for an infant or small child. Further developments in this area included split liver transplantation, in which one liver is used for transplants for two recipients, and living donor liver transplantation, in which a portion of a healthy person's liver is removed and used as the allograft. Living donor liver transplantation for pediatric recipients involves removal of approximately 20% of the liver (Couinaud segments 2 and 3).

Further advance in liver transplant involves only resection of the lobe of the liver involved in tumors and the tumor-free lobe remains within the recipient. This speeds up the recovery and the patient stay in the hospital quickly shortens to within 5–7 days.

Many major medical centers are now using radiofrequency ablation of the liver tumor as a bridge while awaiting for liver transplantation. This technique has not been used universally and further investigation is warranted.

Immunosuppressive management

Like most other allografts, a liver transplant will be rejected by the recipient unless immunosuppressive drugs are used. The immunosuppressive regimens for all solid organ transplants are fairly similar, and a variety of agents are now available. Most liver transplant recipients receive corticosteroids plus a calcineurin inhibitor such as tacrolimus or ciclosporin plus a purine antagonist such as mycophenolate mofetil. Clinical outcome is better with tacrolimus than with ciclosporin during the first year of liver transplantation.[2][3] If the patient has a co-morbidity such as active hepatitis B, high doses of hepatitis B immunoglubins are administrated in liver transplant patients.

Liver transplantation is unique in that the risk of chronic rejection also decreases over time, although the great majority of recipients need to take immunosuppressive medication for the rest of their lives. It is possible to be slowly taken off anti rejection medication but only in certain cases. It is theorized that the liver may play a yet-unknown role in the maturation of certain cells pertaining to the immune system. There is at least one study by Thomas E. Starzl's team at the University of Pittsburgh which consisted of bone marrow biopsies taken from such patients which demonstrate genotypic chimerism in the bone marrow of liver transplant recipients.

Graft rejection

After a liver transplantation, there are three types of graft rejection that may occur. They include hyperacute rejection, acute rejection and chronic rejection. Hyperacute rejection is caused by preformed anti-donor antibodies. It is characterized by the binding of these antibodies to antigens on vascular endothelial cells. Complement activation is involved and the effect is usually profound. Hyperacute rejection happens within minutes to hours after the transplant procedure. Unlike hyperacute rejection, which is B cell mediated, acute rejection is mediated by T cells. It involves direct cytotoxicity and cytokine mediated pathways. Acute rejection is the most common and the primary target of immunosuppressive agents. Acute rejection is usually seen within days or weeks of the transplant. Chronic rejection is the presence of any sign and symptom of rejection after 1 year. The cause of chronic rejection is still unknown but an acute rejection is a strong predictor of chronic rejections. Liver rejection may happen anytime after the transplant. Lab findings of a liver rejection include abnormal AST, ALT, GGT and liver function values such as prothrombin time, ammonia level, bilirubin level, albumin concentration, and blood glucose. Physical findings include encephalopathy, jaundice, bruising and bleeding tendency. Other nonspecific presentation are malaise, anorexia, muscle ache, low fever, slight increase in white blood count and graft-site tenderness.

Results

Prognosis is quite good, but those with certain illnesses may differ.[4] There is no exact model to predict survival rates; those with transplant have a 58% chance of surviving 15 years.[5] Failure of the new liver occurs in 10% to 15% of all cases. These percentages are contributed to by many complications. Early graft failure is probably due to preexisting disease of the donated organ. Others include technical flaws during surgery such as revascularization that may lead to a nonfunctioning graft.

Living donor transplantation

Living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) has emerged in recent decades as a critical surgical option for patients with end stage liver disease, such as cirrhosis and/or hepatocellular carcinoma often attributable to one or more of the following: long-term alcohol abuse, long-term untreated hepatitis C infection, long-term untreated hepatitis B infection. The concept of LDLT is based on (1) the remarkable regenerative capacities of the human liver and (2) the widespread shortage of cadaveric livers for patients awaiting transplant. In LDLT, a piece of healthy liver is surgically removed from a living person and transplanted into a recipient, immediately after the recipient’s diseased liver has been entirely removed.

Historically, LDLT began with terminal pediatric patients, whose parents were motivated to risk donating a portion of their compatible healthy livers to replace their children's failing ones. The first report of successful LDLT was by Dr. Christoph Broelsch at the University of Chicago Medical Center in November 1989, when two-year-old Alyssa Smith received a portion of her mother's liver.[6] Surgeons eventually realized that adult-to-adult LDLT was also possible, and now the practice is common in a few reputable medical institutes. It is considered more technically demanding than even standard, cadaveric donor liver transplantation, and also poses the ethical problems underlying the indication of a major surgical operation (hemihepatectomy or related procedure) on a healthy human being. In various case series, the risk of complications in the donor is around 10%, and very occasionally a second operation is needed. Common problems are biliary fistula, gastric stasis and infections; they are more common after removal of the right lobe of the liver. Death after LDLT has been reported at 0% (Japan), 0.3% (USA) and <1% (Europe), with risks likely to decrease further as surgeons gain more experience in this procedure.[7] Since the law was changed to permit altruistic non-directed living organ donations in the UK in 2006, the first altruistic living liver donation took place in Britain in December 2012.[8]

In a typical adult recipient LDLT, 55 to 70% of the liver (the right lobe) is removed from a healthy living donor. The donor's liver will regenerate approaching 100% function within 4–6 weeks, and will almost reach full volumetric size with recapitulation of the normal structure soon thereafter. It may be possible to remove up to 70% of the liver from a healthy living donor without harm in most cases. The transplanted portion will reach full function and the appropriate size in the recipient as well, although it will take longer than for the donor.[9]

Living donors are faced with risks and/or complications after the surgery. Blood clots and biliary problems have the possibility of arising in the donor post-op, but these issues are remedied fairly easily. Although death is a risk that a living donor must be willing to accept prior to the surgery, the mortality rate of living donors in the United States is low. The LDLT donor's immune system does diminish as a result of the liver regenerating, so certain foods which would normally cause an upset stomach could cause serious illness.

Liver donor requirements

Any member of the family, parent, sibling, child, spouse or a volunteer can donate their liver. The criteria for a liver donation include:

- Being in good health

- Having a blood type that matches or is compatible with the recipient's, although some centres now perform blood group incompatible transplants with special immuno suppression protocols

- Having a charitable desire of donation without financial motivation

- Being between 18 and 60 years old

- Being of similar or bigger size than the recipient

- Before one becomes a living donor, the donor must undergo testing to ensure that the individual is physically fit. Sometimes CT scans or MRIs are done to image the liver. In most cases, the work up is done in 2–3 weeks.[10]

Complications

Living donor surgery is done at a major center. Very few individuals require any blood transfusions during or after surgery. All potential donors should know there is a 0.5 to 1.0 percent chance of death. Other risks of donating a liver include bleeding, infection, painful incision, possibility of blood clots and a prolonged recovery.[11] The vast majority of donors enjoy complete and full recovery within 2–3 months.

Pediatric transplantation

In children, living liver donor transplantations have become very accepted. The accessibility of adult parents who want to donate a piece of the liver for their children/infants has reduced the number of children who would have otherwise died waiting for a transplant. Having a parent as a donor also has made it a lot easier for children - because both patients are in the same hospital and can help boost each other's morale.[12]

Benefits

There are several advantages of living liver donor transplantation over cadaveric donor transplantation, including:

- Transplant can be done on an elective basis because the donor is readily available

- There are fewer possibilities for complications and death than there would be while waiting for a cadaveric organ donor

- Because of donor shortages, UNOS has placed limits on cadaveric organ allocation to foreigners who seek medical help in the USA. With the availability of living donor transplantation, this will now allow foreigners a new opportunity to seek medical care in the USA.

Screening for donors

Living donor transplantation is a multidisciplinary approach. All living liver donors undergo medical evaluation. Every hospital which performs transplants has dedicated nurses that provide specific information about the procedure and answer questions that families may have. During the evaluation process, confidentiality is assured on the potential donor. Every effort is made to ensure that organ donation is not made by coercion from other family members. The transplant team provides both the donor and family thorough counseling and support which continues until full recovery is made.[13]

All donors are assessed medically to ensure that they can undergo the surgery. Blood type of the donor and recipient must be compatible but not always identical. Other things assessed prior to surgery include the anatomy of the donor liver. However, even with mild variations in blood vessels and bile duct, surgeons today are able to perform transplantation without problems. The most important criterion for a living liver donor is to be in excellent health.[14]

Controversy over eligibility for alcoholics

The high incidence of liver transplants given to those with alcoholic cirrhosis has led to a recurring controversy regarding the eligibility of such patients for liver transplant. The controversy stems from the view of alcoholism as a self-inflicted disease and the perception that those with alcohol-induced damage are depriving other patients who could be considered more deserving.[15] It is an important part of the selection process to differentiate transplant candidates who suffer from alcoholism as opposed to those who were susceptible to moderate non-dependent alcohol use. The latter who retain control of alcohol use have a good prognosis following transplantation. Once a diagnosis of alcoholism has been established, however, it is necessary to assess the likelihood of future sobriety.[16]

Famous recipients

- Éric Abidal (born 1979), French footballer (Olympique Lyonnais, FC Barcelona), transplant in 2012

- Gregg Allman (born 1947), American musician (The Allman Brothers Band), transplant in 2010

- George Best (1946-2005), Northern-Irish footballer (Manchester United), transplant in 2002 (survival: 3 years)

- Jack Bruce (1943-2014), English musician (Cream), transplant in 2003 (survival: 11 years)

- Robert P. Casey (1932-2000), American politician (42nd Governor of Pennsylvania), transplant in 1993 (survival: 7 years)

- David Crosby (born 1941), American musician (The Byrds, Crosby Stills, Nash (& Young)), transplant in 1994

- Gerald Durrell (1925-1995), British zookeeper (Durrell Wildlife Park), transplant in 1994 (survival <1 year)

- Shelley Fabares (born 1944), American actress (The Donna Reed Show, Coach) and singer ("Johnny Angel"), transplant in 2000

- Freddy Fender (1937-2006), American musician ("Before the Next Teardrop Falls," "Wasted Days and Wasted Nights"), transplant in 2004 (survival: 2 years)

- "Superstar" Billy Graham (born 1943), American wrestler (WWF), transplant in 2002

- Larry Hagman (1931-2012), American actor (Dallas, Harry and Tonto, Nixon, Primary Colors), transplant in 1995 (survival: 17 years)

- Steve Jobs (1955-2011), American businessman (Apple Inc.), transplant in 2009, (survival: 2 years)

- Chris Klug (born 1972), American snowboarder, transplant in 2000

- Evel Knievel (1938-2007), American stunt performer, transplant in 1999 (survival: 8 years)

- Phil Lesh (born 1940), American musician (Grateful Dead), transplant in 1998

- Linda Lovelace (1949-2002), American pornographic actress (Deep Throat), transplant in 1987 (survival: 15 years)

- Mickey Mantle (1931-1995), American baseball player (New York Yankees), transplant in 1995 (survival: <1 year)

- Jim Nabors (born 1930), American actor (The Andy Griffith Show), transplant in 1994

- John Phillips (1935-2001), American musician (The Mamas & the Papas), transplant in 1992 (survival: 9 years)

Preservation of the liver before transplantation

Between removal from donor and transplantation into the recipient the liver is cooled in an ice-cold preservation solution. The cold temperature slows down deterioration and solution is designed to counteract the unwanted effects of cold ischemia. Besides this method of static cold storage, various dynamic preservation methods are under development, including machine perfusion. Machine perfusion restores a flow through the liver while it's outside the body (ex vivo). This is currently being investigated at cold (hypothermic), body temperature (normothermic), and under body temperature (subnormothermic). Hypothermic machine perfusion has been used successfully at Columbia University and at the University of Zurich.[17][18] A 2014 study published in Nature Medicine showed that the liver preservation time could be significantly extended using a technique called Supercooling, which preserves the liver at subzero temperatures (-6 °C) [19]

References

- 1 2 Mazza, Giuseppe; De Coppi, Paolo; Gissen, Paul; Pinzani, Massimo (August 2015). "Hepatic regenerative medicine". Journal of Hepatology. 63 (2): 523–524. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2015.05.001.

- ↑ Haddad et al. 2006.

- ↑ O'Grady et al. 2002.

- ↑ http://www.innovations-report.com/html/reports/medicine_health/report-22829.html

- ↑ https://www.organdonation.nhs.uk/statistics/presentations/pdfs/april_05/liver_life_expectancy.pdf

- ↑ http://www.uchicagokidshospital.org/specialties/transplant/patient-stories/alyssa-liver.html

- ↑ Umeshita et al. 2003.

- ↑ "First UK live liver donation to a stranger takes place.". BBC News. 23 January 2013. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- ↑ http://www.reachmd.com/xmsegment.aspx?sid=1675

- ↑ Who can be a Donor? - University of Maryland Medical Center, Retrieved on 2010-01-20.

- ↑ Liver Transplant, Retrieved on 2010-01-20.

- ↑ hat I need to know about Liver Transplantation, National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse (NDDIC), Retrieved on 2010-01-20.

- ↑ Liver Donor: All you need to know, Retrieved on 2010-01-20.

- ↑ Liver Transplant Program And Center for Liver Disease, University of Southern California Department of Surgery, Retrieved on 2010-01-20.

- ↑ http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/mouse-man/200902/do-alcoholics-deserve-liver-transplants

- ↑ http://www.bsg.org.uk/images/stories/docs/clinical/guidelines/liver/adult_liver.pdf

- ↑ Graham & Guarrera 2015.

- ↑ Template:Cite web .

- ↑ http://www.nature.com/nm/journal/v20/n7/full/nm.3588.html

Sources

- Guarrera, James V. (2015). ""Resuscitation" of marginal liver allografts for transplantation with machine perfusion technology". Journal of Hepatology. Elsevier. 61 (2): 418–431. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2014.04.019.

|first1=missing|last1=in Authors list (help)

- Haddad, E. M.; McAlister, V. C.; Renouf, E.; Malthaner, R.; Kjaer, M. S.; Gluud, L. L. (2006). "Cyclosporin versus tacrolimus for liver transplanted patients". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 18 (4): CD005161. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005161.pub2. PMID 17054241.

- O'Grady, J. G.; Burroughs, A.; Hardy, P.; Elbourne, D.; Truesdale, A.; The UK and Ireland Liver Transplant Study Group (2002). "Tacrolimus versus microemulsified ciclosporin in liver transplantation: the TMC randomised controlled trial". Lancet. 360 (9340): 1119–1125. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11196-2. PMID 12387959.

- Umeshita, K.; Fujiwara, K.; Kiyosawa, K.; Makuuchi, M.; Satomi, S.; Sugimachi, K.; Tanaka, K.; Monden, M.; Japanese Liver Transplantation Society (2003). "Operative morbidity of living liver donors in Japan". Lancet. 362 (9385): 687–690. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14230-4. PMID 12957090.

Further reading

- Eghtesad B, Kadry Z, Fung J (2005). "Technical considerations in liver transplantation: what a hepatologist needs to know (and every surgeon should practice)". Liver Transpl. 11 (8): 861–71. doi:10.1002/lt.20529. PMID 16035067.

- Adam R, McMaster P, O'Grady JG, Castaing D, Klempnauer JL, Jamieson N, Neuhaus P, Lerut J, Salizzoni M, Pollard S, Muhlbacher F, Rogiers X, Garcia Valdecasas JC, Berenguer J, Jaeck D, Moreno Gonzalez E (2003). "Evolution of liver transplantation in Europe: report of the European Liver Transplant Registry". Liver Transpl. 9 (12): 1231–43. doi:10.1016/j.lts.2003.09.018. PMID 14625822.

- Reddy S, Zilvetti M, Brockmann J, McLaren A, Friend P (2004). "Liver transplantation from non-heart-beating donors: current status and future prospects". Liver Transpl. 10 (10): 1223–32. doi:10.1002/lt.20268. PMID 15376341.

- Tuttle-Newhall JE, Collins BH, Desai DM, Kuo PC, Heneghan MA (2005). "The current status of living donor liver transplantation". Curr Probl Surg. 42 (3): 144–83. doi:10.1067/j.cpsurg.2004.12.003. PMID 15859440.

- Martinez OM, Rosen HR (2005). "Basic concepts in transplant immunology". Liver Transpl. 11 (4): 370–81. doi:10.1002/lt.20406. PMID 15776458.

- Krahn LE, DiMartini A (2005). "Psychiatric and psychosocial aspects of liver transplantation". Liver Transpl. 11 (10): 1157–68. doi:10.1002/lt.20578. PMID 16184540.

- Nadalin S, Malagò M, et al. (2007). "Current trends in live liver donation". Transpl. Int. 20 (4): 312–30. doi:10.1111/j.1432-2277.2006.00424.x. PMID 17326772.

- Vohra V (2006). "Liver transplantation in India". Int Anesthesiol Clin. 44 (4): 137–49. doi:10.1097/01.aia.0000210810.77663.57. PMID 17033486.

- Strong RW (2006). "Living-donor liver transplantation: an overview". J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 13 (5): 370–7. doi:10.1007/s00534-005-1076-y. PMID 17013709.

- Fan ST (2006). "Live donor liver transplantation in adults". Transplantation. 82 (6): 723–32. doi:10.1097/01.tp.0000235171.17287.f2. PMID 17006315.

External links

- Liver disease, at Columbia University Department of Surgery

- Liver Transplant India, by Dr. A.S. Soin

- UNOS: United Network of Organ Sharing, U.S.

- Organ Procurement and Transplantation Center, U.S.

- American Liver Foundation

- Vierling JM (2005). "Management of HBV Infection in Liver Transplantation Patients". Int J Med Sci. 2 (1): 41–49. doi:10.7150/ijms.2.41. PMC 1142224

. PMID 15968339.

. PMID 15968339. - Schiano TD, Martin P (2006). "Management of HCV infection and liver transplantation". Int J Med Sci. 3 (2): 79–83. doi:10.7150/ijms.3.79. PMC 1415839

. PMID 16614748.

. PMID 16614748. - Herrine SK, Navarro VJ (2006). "Antiviral therapy of HCV in the cirrhotic and transplant candidate". Int J Med Sci. 3 (2): 75–8. doi:10.7150/ijms.3.75. PMC 1415848

. PMID 16614747.

. PMID 16614747. - Living Donors Online

- Liver Transplantation Guide and Liver Transplant Surgery in India

- History of pediatric liver transplantation

- ABC Salutaris: Living Donor Liver Transplant

- All You Need to Know about Adult Living Donor Liver Transplantation

- Facts about Liver Transplantation

- Children's Liver Disease Foundation

- The Toronto Video Atlas of Liver, Pancreas and Transplant Surgery - Living Donor Right Lobe Liver Transplant video (recipient)

- The Toronto Video Atlas of Liver, Pancreas and Transplant Surgery - Living Donor Right Lobe Liver Transplant video (donor)

- The Toronto Video Atlas of Liver, Pancreas and Transplant Surgery - Living Donor Left Lobe Liver Transplant video (donor)

- The Toronto Video Atlas of Liver, Pancreas and Transplant Surgery - Living Donor Left Lateral Lobe Liver Transplant video (donor)

- The Toronto Video Atlas of Liver, Pancreas and Transplant Surgery - Living Donor Right Posterior Sectionectomy (Segments 6/7) Liver Transplant video (donor)