Mongmit State

| Mongmit | |||||

| State of the Shan States | |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| History | |||||

| • | State founded | 1238 | |||

| • | Abdication of the last Saopha | 1959 | |||

| Area | |||||

| • | 1901 | 9,225 km2 (3,562 sq mi) | |||

| Population | |||||

| • | 1901 | 44,208 | |||

| Density | 4.8 /km2 (12.4 /sq mi) | ||||

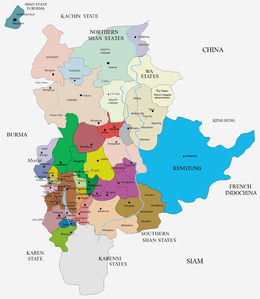

Mongmit or Möngmit (Burmese: Momeik) was a Shan state in the Northern Shan States in what is today Burma. The capital was Mongmit town. The state included the townships of Mongmit and Kodaung (Kawdaw, now Mabein Township).[1]

History

According to tradition Mongmit has its origins in an ancient state named Gandalarattha that was founded before 1000 AD.[2] Mongmit, formerly part of Hsenwi State, was founded in 1238. Thirteen villages of the Mogok Stone Tract were given to Mongmit in 1420 as a reward for helping Yunnan raid Chiang Mai. In 1465, Nang Han Lung, the daughter-in-law of the Saopha (Sawbwa in Burmese) of Mongmit, sent ruby as separate tribute from Hsenwi and succeeded in keeping the former possessions of Hsenwi until 1484 when Mogok was ceded to the Burmese kings.[3][4] It was however not until 1597 that the Saopha of Mongmit was forced to exchange Mogok and Kyatpyin with Tagaung, and they were formally annexed by royal edict.[4][5]

Earlier in 1542, when the Shan ruler of Ava Thohanbwa (1527–1543) marched with the Saophas of Mongmit, Mongyang, Hsipaw, Mogaung, Bhamo and Yawnghwe to come to the aid of Prome against the Burmese, he was defeated by Bayinnaung. In 1544, Hkonmaing (1543-6), Saopha of Onbaung or Hsipaw and successor to Thohanbwa, attempted to regain Prome, with the help of Mongmit, Mongyang, Monè, Hsenwi, Bhamo and Yawnghwe, only to be defeated by King Tabinshwehti (1512–1550).[3]

Bayinnaung succeeded in three campaigns, 1556-9, to reduce the Shan states of Mongmit, Mohnyin, Mogaung, Mongpai, Saga, Lawksawk, Yawnghwe, Hsipaw, Bhamo, Kalay, Chiang Mai, and Linzin, before he raided up the Taping and Shweli Rivers in 1562.[3]

A bell donated by King Bayinnaung (1551–1581) at Shwezigon Pagoda in Bagan has inscriptions in Burmese, Pali and Mon recording the conquest of Mongmit and Hsipaw on 25 January 1557, and the building of a pagoda at Mongmit on 8 February 1557.[6]

British rule

The Saopha of Mongmit had just died at the time of the British annexation in 1885 leaving a minor as heir, and the administration at Mongmit was weak. It was included under the jurisdiction of the Commissioner of the Northern Division instead of the Superintendent of the Northern Shan States. A pretender named Hkam Leng came to claim the title, but he was rejected by the ministers. A Burmese prince called Saw Yan Naing, who had risen up against the British, fled to the area and joined forces with Hkam Leng, and caused a great deal of problems during 1888-9 to the Hampshire Regiment stationed at Mongmit.[7]

Sao Hkun Hkio, Saopha of Mongmit, was one of the seven Saophas on the Executive Committee of the Shan State Council formed after the first Panglong Conference in March 1946. On 16 January 1947, they sent two memoranda, whilst a Burmese delegation headed by Aung San was in London, to the British Labour government of Clement Attlee demanding equal political footing as Burma proper and full autonomy of the Federated Shan States.[8] He was not one of the six Saophas who signed the Panglong Agreement on 12 February 1947.[9] The Cambridge-educated Sao Hkun Hkio however became the longest serving Foreign Minister of Burma after independence in 1948 until the military coup of Ne Win in 1962, with only short interruptions, the longest one of which being between 1958 and 1960 during Ne Win's caretaker government.[10][11]

Rulers

The rulers of Mongmit bore the title of Saohpa; their ritual style was Gantalarahta Maha Thiriwuntha Raza.[2]

Saophas

- 1830? - 1837 Maung Hmaing

- 1837 - 1840 Maung E Pu (1st time)

- 1840 - 1850 ....

- 1850 - 1851 Maung E Pu (2nd time)

- 1851 - 1858 Hkun Te

- 1858 - 1861 Haw Kyin

- 1861 - 1862 Kaw San -Regent

- 1862 - 1867 Maung Yo

- 1867 - 1874 Hkam Mo

- 1874 - 1883 Kan Ho (d. 1883)

- 1883 - 1936 Sao Kin Maung Gye (b. 1883 - d. 1936)

- 1883 - 1887 Sao Maung -Regent (1st time) (b. 1848 - d. 1929)

- Apr 1887 - Apr 1889 Hkan U -Regent (b. 18.. - d. 1903)

- Apr 1889 - 2 Feb 1892 Sao Maung -Regent (2nd time) (s.a.)

- Feb 1936 - 1952 Sao Hkun Hkio (b. 1912 - d. 1990)

References

- ↑ Imperial Gazetteer of India, v. 17, p. 404.

- 1 2 Ben Cahoon (2000). "World Statesmen.org: Shan and Karenni States of Burma". Retrieved 7 July 2014.

- 1 2 3 Harvey, G E. History of Burma: From the Earliest Times to 10 March 1824. Asian Educational Services, 2000. pp. 101, 107, 109, 165–6. ISBN 978-81-206-1365-2. Retrieved 2009-02-17.

- 1 2 Morgan, Diane. Fire and Blood: Rubies in Myth, Magic, and History. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2007. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-275-99304-7. Retrieved 2009-02-17.

- ↑ Hughes, Richard. "Ruby & Sapphire, chapter12:World Sources". Ruby-Sapphire.com. Retrieved 2009-02-17.

- ↑ U Thaw Kaung. "Accounts of King Bayinnaung's Life and Hanthawady Hsinbyu-myashin Ayedawbon, a Record of his Campaigns". Chulalongkorn University. Retrieved 2009-02-25.

- ↑ Crosthwaite, Charles. The Pacification of Burma. Routledge, 1968. pp. 267–280. ISBN 978-0-7146-2004-6. Retrieved 2009-02-25.

- ↑ "Shans send Memoranda To His Majesty's Government". S.H.A.N. Retrieved 2009-02-28.

- ↑ "The Panglong Agreement, 1947". Online Burma/Myanmar Library. Retrieved 2009-02-28.

- ↑ "Foreign ministers". rulers.org. Retrieved 2009-03-16.

- ↑ "Mrs. Beatrice Mabel Hkio". Hansard. 5 June 1967. Retrieved 2009-03-16.

External links

- "WHKMLA : History of the Shan States". 18 May 2010. Retrieved 21 December 2010.

Coordinates: 23°7′N 96°41′E / 23.117°N 96.683°E