Mahmud Tarzi

| Allamah Mahmud Tarzi | |

|---|---|

|

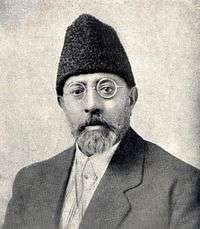

Mahmud Tarzi in 1919 | |

| Foreign Minister of Afghanistan | |

|

In office 1924–1927 | |

| Monarch | Amanullah Khan |

|

In office 1919–1922 | |

| Monarch | Habibullah Khan |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

August 23, 1865 Ghazni, Afghanistan |

| Died |

November 22, 1933 Istanbul, Turkey |

| Nationality | Afghan, Turkish |

| Religion | Islam |

Mahmud Beg Tarzi (Pashto: محمود طرزۍ, Dari: محمود بیگ طرزی; August 23, 1865 – November 22, 1933) was a politician and one of Afghanistan's greatest intellectuals.[1] He is known as the father of Afghan journalism. As a prominent modern thinker, he became a key figure in the history of Afghanistan, following the lead of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in Turkey by working for modernization and secularization, and strongly opposing religious extremism and obscurantism. Tarzi emulated the Young Turks coalition.[2] Perhaps to the point of the emulation Pashtun nationalism.

Early years

Tarzi was born on 23 August 1865 in Ghazni, Afghanistan. An ethnic Pashtun, his father was Sardar Ghulam Muhammad Tarzi, leader of the Mohammadzai royal house of Kandahar and a well-known poet. His mother belonged to Popalzai tribe.[3] In 1881, shortly after Emir Abdur Rahman Khan came to power. Mahmud's father and the rest of the Tarzi family were expelled from Afghanistan. They first travelled to Karachi, Sindh, where they lived from January 1882 to March 1885. They then moved to the Ottoman Empire.

Mahmud began to explore the Middle East, he made pilgrimage to Mecca, visited Paris, and toured the eastern Mediterranean. He also encountered Jamal ad-Din al-Afghani in Constantinople.[3] On a second trip to Damascus, Syria, in 1891, Tarzi married the daughter of Sheikh Saleh Al-Mossadiah, a muezzin of the Umayyad mosque. She became his second wife, the first was an Afghan who had died in Damascus. Tarzi stayed in Turkey until the age of 35, where he became fluent in a number of languages, including his native tongue Pashto as well as Dari, Turkish, French, Arabic, and Urdu.[4]

A year after Emir Abdur Rahman Khan's death in 1901, Habibullah Khan invited the Tarzi family back to Afghanistan. Mahmud Tarzi was given a post in the government. There he began to introduce Western ideas in Afghanistan. If there is a single person responsible for the modernization of Afghanistan in the first two decades of the twentieth century it was Tarzi. Tarzi's daughter, Soraya Tarzi, married King Amanullah Khan and become Queen of Afghanistan. Mahmud Tarzi took up a critical role in the history of Afghanistan, from famed poet to progressive leader.[4]

Journalism and poetry

One of Tarzi's earliest works was known as the Account of a Journey (Sayahat-Namah-e Manzum), which was published in Lahore, British India (now Pakistan). However, Tarzi's most influential work – and the foundation of journalism in Afghanistan – was his publishing of Seraj-al-Akhbar. This newspaper was published bi-weekly from October 1911 to January 1919.[5] It played an important role in the development of an Afghan modernist movement, serving as a forum for a small, enlightened group of young Afghans, who provided the ethical justification and basic tenets of Afghan nationalism and modernism. Tarzi also published Seraj-al-Atfal (Children's Lamp), the first Afghan publication aimed at a juvenile audience.[4]

Tarzi was the first who introduced the novel in Afghanistan and translated many English and French novels to Dari and Pashto. He also contributed in editing, translations, and modernization of the Afghan press. He translated into Dari and Pashto many major works of European authors, such as Around the World in Eighty Days, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, The Mysterious Island, International Law (from Turkish), and the History of the Russo-Japanese War. When he lived in Turkey and Syria, he immersed himself in reading and research, using Western literary and scientific sources. In Damascus, Tarzi wrote The Garden of Learning, containing choice articles about literary, artistic, travel and scientific matters. Another book entitled The Garden of Knowledge (later published in Kabul), concludes with an article "My beloved country, Afghanistan", in which he tells his Afghan countrymen how much he longs for his native land and recalls with nostalgia the virtues of its climate, mountains and deserts. In 1914, his novel Travel Across Three Continents in Twenty-Nine Days published. In the preface, he makes an apt comment about travel and history:

"Although age has its normal limits, it may be extended by two things-the study of history and by travel. Reading history broadens one's perception of the creation of the world, while travel extends one's field of vision."[1]

He was instrumental in developing a modern literary community his last two decades in Afghanistan. Many of Tarzi's writings would be published after his death.

Politics

Like most other Afghan leaders, Tarzi was an Afghan nationalist who held many government positions in his life. He was a reform-minded individual amongst his extended family members whom ruled Afghanistan at the beginning of the 20th century and not unlike his father Sardar Ghulam Muhammad Khan Tarzi. After King Amanullah ascended the throne, Tarzi became Afghan Foreign Minister in 1919. Shortly thereafter, the Third Anglo-Afghan War began. After the national independence from the British in 1919, Tarzi established Afghan Embassies in London, Paris, and other capitals of the world. Tarzi would also go on to play a large role in the declaration of Afghanistan's independence. From 1922 to 1924, he served as Ambassador in Paris, France. He was then again placed as Foreign Minister from 1924 to 1927. Throughout his tenure in Afghanistan, Tarzi was a high government official during the reigns of King Habibullah and his son King Amanullah Khan.[1]

Afghanistan's 1919 Independence

Tarzi effectively guided the second movement of the young constitutionalists called Mashroota Khwah. This led to reviving the first suppressed movement of the constitutionalists in Afghanistan.[4] Tarzi served as high counsel and advisor during this event.

Afghan Peace Conferences

During the Third Anglo-Afghan War in 1919, when Tarzi served as Foreign Minister, British India bombarded Kabul and Jalalabad, over a ton of munitions rained down to Jalalabad in a single day.[1] Tarzi was appointed head of the Afghan Delegation at the peace conferences at Mussoorie 1920 and Kabul 1921. The British, who had dealt with Tarzi before, attempted to reduced Tarzi's energy to get more than they were supposed to. After four months the talks broke up because of the Durand Line. Sir Henry Dobbs led the British delegation to Kabul in January, 1921 – Mahmud Tarzi headed the Afghan group. After 11 months of discussions, the British and Afghans signed a peace treaty normalizing their relations. Although Afghanistan was the winner of the conference – as the British accepted Afghanistan's independence – Tarzi's diplomacy was shown as the British sent a message afterwards to Tarzi, giving their good will toward all tribes.[1]

Social justice and equality

Politically, he held important government positions during the reigns of King Habibullah and son Amanullah. He reached the highest points of government as a chief adviser and Foreign Minister. He was a main force behind Habibullah Khan's social reforms, especially with regard to education. These reforms included changing the medieval schools and madrasah systems, allow publication of books and journals, and lift all restrictions that ban girls and women from the rest of society. He led the charge for modernization – doing so as a strong opponent of religious obscuring. Although very religious, he was strongly against the state establishing a religion, even if it were his own. Early in his career, he was in favour of a united nation that would stretch from modern-day Pakistan to Syria, not to unify a Muslim nation but to stop inner-conflict and tribal wars that were common during that time in history. Tarzi's daughter, Queen Soraya Tarzi, would play a bigger role for social justice, being one of the first and only major feminists in power in Afghanistan's history.

Final years

Many of Tarzi's plans and projects were never started, as the royal house of King Amanullah came to an end by a coup in 1929. Tarzi and his family left Afghanistan and settled in Turkey. He died on November 22, 1933 at the age of 68 in Istanbul, Turkey.

Mahmud Tarzi Cultural Foundation

In September 2005, the Mahmud Tarzi Cultural Foundation (MTCF) was established in Kabul, Afghanistan, with its head office in Mahmud Tarzi High School. The foundation is serving, according to NGO rules as a whole, briefly as, increasing the life quality of children at the educational level, helping their education, building schools, training & health centers, running these facilities and to complete the mentioned services written in the Deed of Foundation by creating financial aid for Afghan students.

A major project that the cultural foundation is starting in 2007 is the Mahmud Tarzi Compound in Afghanistan. This project contains a library and a museum for Tarzi's works, a street children care center in memory of Asma Rasmia (wife of Tarzi) and a women's care center in memory of Queen Soraya (daughter of Tarzi and Queen of Afghanistan).

In order to get necessary funding for the foundation, a business center and a hotel will be built together with the compound. With any profit, the foundation will organize scholarship programmes, publish old and new works of Tarzi, and make contributions to the young authors and litterateurs to whom work for Mahmud Tarzi's ideas.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Biography of Mahmud Tarzi

- ↑ Adamec, Ludwig W. "ḤABIB-ALLĀH". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 2013-04-07.

- 1 2 Schinasi, May. "ṬARZI, MAḤMUD". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 2013-04-07.

- 1 2 3 4 Farhad Azad (ed.). "An Afghan Intellect: Mahmoud Tarzi". Afghan Magazine Article: July – Sept. 1997, by Yama Atta & Hashmat Haidari. afghanmagazine.com. Retrieved 2013-04-07.

- ↑ Chronology: the reigns of Abdur Rahman Khan and Habibullah, 1881–1919

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Mahmud Tarzi |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mahmud Tarzi. |

- Official website

- The Mahmud Tarzi Cultural Foundation (MTCF)

- Old Photo Book – by Mahmud Tarzi

- The Foundation