Maine Centennial half dollar

| United States | |

| Value | 50 cents (0.50 US dollars) |

|---|---|

| Mass | 12.5 g |

| Diameter | 30.61 mm |

| Thickness | 2.15 mm (0.08 in) |

| Edge | Reeded |

| Composition |

|

| Silver | 0.36169 troy oz |

| Years of minting | 1920 |

| Mintage | 50,028 including 28 pieces for the Assay Commission |

| Mint marks | None, all pieces struck at the Philadelphia Mint without mint mark |

| Obverse | |

| |

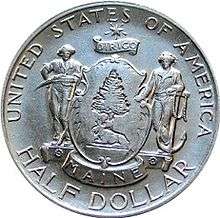

| Design | State seal of Maine |

| Designer | Anthony de Francisci, based on sketches by an unknown artist |

| Design date | 1920 |

| Reverse | |

| |

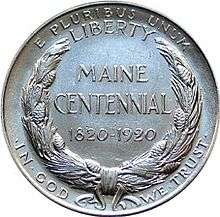

| Design | Pine wreath |

| Designer | Anthony de Francisci, based on sketches by an unknown artist |

| Design date | 1920 |

The Maine Centennial half dollar is a commemorative coin struck in 1920 by the United States Bureau of the Mint. It was sculpted by Anthony de Francisci, following sketches by an unknown artist from the State of Maine.

Officials in Maine wanted a commemorative half dollar to circulate as an advertisement for the centennial of the state's admission to the Union, and of the celebrations there in commemoration of it. A bill to allow that passed Congress without opposition, but then the state's centennial commission decided to charge a premium. The Commission of Fine Arts disliked the proposed design, and urged changes, but Maine officials insisted, and de Francisci converted the sketches to plaster models, from which coinage dies could be made.

Fifty thousand pieces, half the authorized mintage, were struck for release to the public. They were issued too late to be sold at the centennial celebrations in Portland, but eventually the coins were all sold to the public, though relatively few to coin collectors. They catalog for hundreds to thousands of dollars, depending on condition.

Inception and legislation

Governor Carl Milliken and the council of Maine wanted a half dollar issued to commemorate the centennial of the state's 1820 admission to the Union. Initially, the idea was to have a circulating commemorative that could advertise the centennial celebrations in Maine, but subsequent to the approval of the legislation, the centennial commission decided to issue it at a premium.[1]

Legislation for a Maine Centennial half dollar was introduced in the House of Representatives by that state's John A. Peters on February 11, 1920, with the bill designated as H.R. 12460.[2] It was referred to the Committee on Coinage, Weights and Measures, of which Indiana Congressman Albert Vestal was the chairman. That committee held hearings on the bill on February 23, 1920, first considering a two-year extension for the National Screw-Thread Commission. Once the committee had heard of the standardization of screw threads, Congressman Peters addressed the committee, of which he was not a member, regarding the Maine coinage proposal, telling of the history of the state and citizens' desire to celebrate the centennial, including with a commemorative coin. He stated that he had spoken with the Director of the Mint, Raymond T. Baker, who had told Peters that he and Treasury Secretary David F. Houston planned to give their endorsement of the bill, the text of which had been borrowed from the bill authorizing the 1918 Illinois Centennial half dollar. Vestal had also gone to see Baker, and confirmed the information. Ohio's William A. Ashbrook recalled that he had been a member of the committee that had approved the Illinois bill; he had favored it and now favored the Maine bill. Minnesota's Oscar E. Keller asked Peters to confirm there would be no expense to the government, which Peters did. [3] Clay Stone Briggs of Texas wanted to know if the Maine bill's provisions were identical to those of the Illinois act, and Peters confirmed it.[4] On March 20, Vestal filed a report on behalf of his committee, recommending that the House pass the bill, and reproducing a letter from Houston stating that the Treasury had no objection.[5]

Three coinage bills—Maine Centennial, Alabama Centennial, and Pilgrim Tercentenary—were considered in that order by the House of Representatives on April 21, 1920. After Peters addressed the House in favor of the Maine bill, Connecticut's John Q. Tilson inquired if the proposed coin would replace the existing design (the Walking Liberty half dollar) for the rest of the year; Peters explained that it would not, only 100,000 coins would bear the commemorative design.[6] John Franklin Miller of Washington state asked who would bear the expenses of the coinage dies, and Peters responded that the state of Maine would. Virginia's Andrew Jackson Montague asked if the Treasury Department had endorsed the bill, and Peters informed him that both Houston and Baker had. Vestal asked that the bill be passed, but Ohio's Warren Gard asked a number of questions, centering around what would happen to the coins once they entered circulation; Peters stated that they would, once issued, be treated as ordinary half dollars. In response to questions by Gard, Peters explained that although Maine would pay for the dies, they would become federal government property. Peters added that though would be no statewide celebration in Maine for the centennial, there would be local observances. Gard had no further questions about the Maine bill (he would also quiz the sponsors of the Alabama and Pilgrim bills), and on Vestal's motion it passed without recorded dissent.[7]

The following day, April 22, 1920, the House reported its passage of the Maine bill to the Senate.[8] The bill was referred to the Senate Committee on Banking and Currency; on April 28, Connecticut's George P. McLean reported it back with a recommendation it pass.[9] On May 3, McLean asked that the three coin bills (Maine, Alabama and Pilgrim) be considered by the Senate immediately, rather than awaiting their turns, but Utah Senator Reed Smoot objected: Smoot's attempt to bring up an anti-dumping trade bill had just been objected to by Charles S. Thomas of Colorado. Smoot, however, stated if the bills had not been reached by about 2:00 pm, there would probably not be any objection.[10] When McLean tried again to advance the coin bills, Kansas' Charles Curtis asked if there was any urgency. McLean replied that as the three coin bills were to mark ongoing anniversaries, there was a need to have them authorized and get the production process started. All three bills passed the Senate without opposition[11] and the Maine bill was enacted with the signature of President Woodrow Wilson on May 10, 1920.[2]

Preparation

On May 14, 1920, four days after Wilson signed the bill, Director of the Mint Baker sent sketches of the proposed design to the chairman of the Commission of Fine Arts, Charles Moore, for an opinion as to its merits. The design had been prepared by the officials in charge of the centennial commemoration, and had been given to Baker by Peters. Moore forwarded the sketches to the sculptor-member of the Commission, James Earle Fraser. Having received no reply, Moore on May 26 sent a telegram to Fraser telling him that the Maine authorities wanted the coins by June 28. Fraser immediacy replied by telegram, that he disliked the design as it was "ordinary", and that it was an error to approve sketches; a plaster model should be made by a sculptor. Moore expanded on this in a letter to Houston the following day, "our new silver coinage has reached a high degree of perfection because it was designed by competent men. We should not return to the low standards which have formerly prevailed."[12]

Moore in his letter urged a change of design, stating that the sketch, if translated into a coin, "would bring humiliation to the people of Maine".[1] However, Maine officials refused and insisted on the submitted sketches.[13] After discussions among Peters, Moore, and various officials, an agreement was reached whereby the sketches would be converted into plaster models, and Fraser engaged his onetime student, Anthony de Francisci, to do the work. The younger sculptor completed the work by early July, and the models were approved by the Commission on July 9.[14] The Engraving Department at the Philadelphia Mint created the coin dies utilizing de Francisci's models.[13] Either Chief Engraver George T. Morgan, or his assistant, future chief engraver John R. Sinnock, changed the moose and pine tree on the coin from being in relief (as in de Francisci's models), to be sunken into the coin. This was likely in an attempt to improve the striking quality of the coins, and if so, likely had limited success, as the full detail would not appear on many coins.[15]

Design

The obverse of the Maine Centennial half dollar depicts the arms of Maine, based on the state's seal. At its center is a shield with a pine tree, sunken incuse into the coin, and below the tree a moose, lying down. The shield is flaked by two male figures, one bearing a scythe and representing Agriculture; the other, supporting an anchor, represents Commerce. Above the shield is the legend Dirigo, Latin for "I direct", and above that a five-pointed star. Below the shield is a scroll with the state's name. Near the rim are the name of the country and HALF DOLLAR. The reverse contains a wreath of pine needles and cones (Maine is known as the Pine Tree State) around MAINE CENTENNIAL 1820–1920 as well as the various mottoes required by law to be present on the coinage.[16][17]

Numismatist Don Taxay, in his history of commemorative coins speculated that "De [sic] Francisci did not altogether favor them".[18] According to Taxay, the two human figures on the obverse "were too small to retain their beauty after reduction [from the plaster models to coin size] and seem trivial. The reverse, with its wreath of pine coins, is eminently uninspired."[18] Arlie Slabaugh, in his volume on commemoratives, noted that the half dollar "does not resemble the work by the same sculptor for the Peace dollar the following year [1921]."[19]

Art historian Cornelius Vermeule deprecated the Maine half dollar, but did not blame de Francisci, as the piece "was modeled by the sculptor according to required specifications and is therefore not considered typical of his art, or indeed of any art."[20] Vermeule stated, "it looks just like a prize medal for a county fair or school athletic day."[20] Feeling that de Francisci could have insisted on a more artistic design, Vermeule found "the Maine Centennial was not his shining moment".[21]

Production, distribution, and collecting

Celebrations for the state's centennial were held in Maine's largest city, Portland, on July 4, 1920. Peters had hoped to have the half dollars available for distribution then, but because of the design controversy, they were not. He wrote to Assistant Director of the Mint Mary M. O'Reilly on July 14, expressing his frustration at the delay and stating that though the Portland festivities had passed, the state could still get some benefit from the coins if they received them during 1920. Otherwise, "we might as well wait for the next Centennial [in 2020] which I judge would be more convenient and in accordance with the speed at which we are going.[22] He concluded by asking that the Mint let him know of the next obstacle ahead of time. Governor Milliken also wrote, on July 20, reminding Mint officials that the coin was authorized by a special act of Congress, and asking when the first consignment would be ready.[22]

In the late summer of 1920, a total of 50,028 Maine Centennial half dollars were produced at the Philadelphia Mint, with the excess over the round number reserved for inspection and testing at the 1921 meeting of the annual Assay Commission.[23] No special care was taken in the minting; they were ejected into bins and many display bag marks.[24] They were sent to Maine and placed on sale through the Office of the State Treasurer at a price of $1. Thirty thousand sold immediately and they remained on sale though the treasurer's office until all fifty thousand were vended,[23] though this did not happen until at least 1929.[25] Bowers speculated that had the full 100,000 authorized been struck, most of the additional quantity would have been returned to the Mint and melted for lack of buyers.[26] Many pieces were spent in the years after 1920 and entered circulation.[24]

Relatively few sold to the coin collecting community, and the majority of surviving specimens display the effects of careless handling. The 2015 deluxe edition of Richard S. Yeoman's A Guide Book of United States Coins lists the coin at $140 to $685, depending on condition—an exceptional piece sold for $7,050 in 2014.[27]

References

- 1 2 Bowers, pp. 135–36.

- 1 2 "Maine Statehood 100th Anniversary 50-Cent Piece". ProQuest Congressional. Retrieved July 30, 2016. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ House hearings, pp. 3–5.

- ↑ House hearings, pp. 2–4, 8–9.

- ↑ House Committee on Coinage, Weights and Measures (March 20, 1920). "Coinage of 50-Cent Pieces in Commemoration of the Admission of the State of Maine into the Union". (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ 1920 Congressional Record, Vol. 66, Page 5947 (April 21, 1920)

- ↑ 1920 Congressional Record, Vol. 66, Page 5947–5950 (April 21, 1920)

- ↑ 1920 Congressional Record, Vol. 66, Page 5966 (April 22, 1920)

- ↑ 1920 Congressional Record, Vol. 66, Page 6202 (April 28, 1920)

- ↑ 1920 Congressional Record, Vol. 66, Page 6443 (May 3, 1920)

- ↑ 1920 Congressional Record, Vol. 66, Page 6454 (May 3, 1920)

- ↑ Taxay, pp. 39–40.

- 1 2 Bowers, p. 136.

- ↑ Taxay, pp. 40–42.

- ↑ Swiatek & Breen, pp. 147, 150.

- ↑ Swiatek, pp. 110–11.

- ↑ Swiatek & Breen, p. 147.

- 1 2 Taxay, p. 42.

- ↑ Slabaugh, p. 41.

- 1 2 Vermeule, p. 159.

- ↑ Vermeule, p. 160.

- 1 2 Flynn, pp. 296–297.

- 1 2 Swiatek, p. 111.

- 1 2 Flynn, p. 120.

- ↑ Bowers, p. 137.

- ↑ Bowers, p. 138.

- ↑ Yeoman, p. 1125.

Sources

- Bowers, Q. David (1992). Commemorative Coins of the United States: A Complete Encyclopedia. Wolfeboro, NH: Bowers and Merena Galleries, Inc. ISBN 978-0-943161-35-8.

- Flynn, Kevin (2008). The Authoritative Reference on Commemorative Coins 1892–1954. Roswell, GA: Kyle Vick. OCLC 711779330.

- Slabaugh, Arlie R. (1975). United States Commemorative Coinage (second ed.). Racine, WI: Whitman Publishing. ISBN 978-0-307-09377-6.

- Swiatek, Anthony (2012). Encyclopedia of the Commemorative Coins of the United States. Chicago: KWS Publishers. ISBN 978-0-9817736-7-4.

- Swiatek, Anthony; Breen, Walter (1981). The Encyclopedia of United States Silver & Gold Commemorative Coins, 1892 to 1954. New York: Arco Publishing. ISBN 978-0-668-04765-4.

- Taxay, Don (1967). An Illustrated History of U.S. Commemorative Coinage. New York: Arco Publishing. ISBN 978-0-668-01536-3.

- United States House of Representatives Committee on Coinage, Weights and Measures (March 26, 1920). Authorizing Coinage of Memorial 50-Cent Piece for the State of Alabama (PDF). United States Government Printing Office. (subscription required (help)).

- Vermeule, Cornelius (1971). Numismatic Art in America. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-62840-3.

- Yeoman, R.S. (2015). A Guide Book of United States Coins (1st Deluxe ed.). Atlanta, GA: Whitman Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7948-4307-6.

External links

-

Media related to Maine Centennial half dollar at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Maine Centennial half dollar at Wikimedia Commons