Sam Manekshaw

| Field Marshal S H F J Manekshaw MC | |

|---|---|

Field Marshal Sam Manekshaw (pictured wearing general's insignia c. 1970) | |

| Nickname(s) | Sam Bahadur |

| Born |

3 April 1914 Amritsar, Punjab, British India |

| Died |

27 June 2008 (aged 94) Wellington, Tamil Nadu |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch | |

| Years of service | 1934–2008[lower-alpha 1] |

| Rank | Field Marshal |

| Commands held |

|

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards | |

| Spouse(s) | Silloo Bode |

| Signature |

|

Field Marshal Sam Hormusji Framji Jamshedji Manekshaw, MC (3 April 1914 – 27 June 2008), popularly known as Sam Bahadur ("Sam the Brave"), was the Chief of the Army Staff of the Indian Army during the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971, and was subsequently the first Indian Army officer to be promoted to the rank of field marshal. His distinguished military career spanned four decades and five wars, beginning with service in the British Indian Army in World War II.

Though Manekshaw initially thought of pursuing a career as a medical doctor, he later joined the first intake of the Indian Military Academy (IMA) when it was established in 1932. Right from his days at IMA, he proved to be witty and humorous in nature. He was first attached to the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Scots, and then later posted to the 4th Battalion of the 12th Frontier Force Regiment, commonly known as the 54th Sikhs. During action in World War II, he was awarded the Military Cross for gallantry. Following the partition of India in 1947, he was later reassigned to the 16th Punjab Regiment. Owing to the Kashmir and Hyderabad crisis, Manekshaw never commanded a battalion, and was promoted to the rank of brigadier while he was at Military Operations Directorate.

Manekshaw rose to become the 8th Chief of Army Staff in 1969, and under his command, Indian forces conducted victorious campaigns against Pakistan in the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971 that led to the creation of Bangladesh in December 1971. For his services, he was awarded the Padma Vibhushan and the Padma Bhushan, the second and third highest civilian awards of India.

Early life and education

Manekshaw was born on 3 April 1914 in Amritsar, Punjab to Parsi parents, Hormusji Manekshaw, a doctor, and his wife Hilla, who moved to Punjab from the city of Valsad in the coastal Gujarat region.[2][3][4] Sam's father served in the British Indian Army as a captain in the medical services and also participated in World War I.[3] Hormusji and Hilla had six children of which Sam was the fifth one. Fali, Cilla, Jan and Sehroo preceded Sam and Sam was followed Jemi, who later joined the air force as a doctor and was the first Indian to be awarded the air surgeon's wings from Naval Air Station, Pensacola, United States.[3] After completing his schooling in Punjab and Sherwood College, Nainital, and achieving a distinction in the School Certificate of the Cambridge Board, an English language curriculum developed by the University of Cambridge International Examinations, at the age of 15, and he asked his father to send him to London to become a gynaecologist.[5] But his father refused, stating that he was not old enough.[6]

In the meantime, the Indian Military College Committee which was set up in 1931 and chaired by Field Marshal Sir Philip Chetwode recommended the establishment of a military training academy in India to train Indians for commissioning into the army. A three-year course was proposed with an entry age of 18 to 20 years, candidates would be selected on the basis of an examination conducted by the Public Service Commission.[6] After the approval of the committee's recommendation, a formal notification for entrance examination to enrol in the Indian Military Academy (IMA) was issued in the early months of 1932 with the examination to be conducted in the months of June or July.[7]

In an act of rebellion against his father's refusal, Manekshaw took the examination for enrolment into the academy, and was one of the fifteen cadets to be selected through open competition.[lower-alpha 2] He stood sixth in the order of merit.[7]

Training at the Indian Military Academy

Although the academy was formally inaugurated on 10 December 1932 by Chetwode,[7] formal military training for the cadets commenced from 1 October 1932. After being selected into the first batch of the academy—called the "The Pioneers", which produced three future chiefs—Manekshaw (India), Smith Dun (Burma) and Muhammad Musa (Pakistan). Manekshaw proved to be witty during his stay at the academy and had many firsts to his credit. He was the first of the alumni to join the Gorkha Regiment and later the first to serve as the Chief of the Army Staff of India and attain the rank of field marshal.[7] Of the 40 cadets inducted, only 22 were able to complete the course and were commissioned as second lieutenants on 1 February 1935 with their anté-date seniority fixed as 4 February 1934.[8]

Military career

On commissioning, as per the practices of that time, Manekshaw was first attached to the 2nd Battalion, The Royal Scots, a British battalion, and was later posted to the 4th Battalion, 12th Frontier Force Regiment, commonly known as the 54th Sikhs.[9][10][11]

World War II

During World War II, the then-Captain Manekshaw saw action in Burma in the 1942 campaign on the Sittang River with the 4th Battalion, 12th Frontier Force Regiment,[12][13] and had the rare distinction of being honoured for his bravery on the battlefield itself. During the fighting around Pagoda Hill, a key position on the left of the Sittang bridgehead, he led his company in a counter-attack against the invading Japanese Army and despite suffering 50% casualties the company managed to achieve its objective. After capturing the hill, Manekshaw was hit by a burst of light machine gun fire and was severely wounded in the stomach.[14] Observing the battle, Major General David Cowan, the then commander of the 17th Infantry Division, spotted Manekshaw holding on to life and, having witnessed his valour in the face of stiff resistance, rushed over to him. Fearing that Manekshaw would die, the general pinned his own Military Cross ribbon to Manekshaw saying, "A dead person cannot be awarded a Military Cross."[13][15] The official recommendation for the MC states that the success of the attack "was largely due to the excellent leadership and bearing of Captain Manekshaw". This award was made official with the publication of the notification in a supplement to the London Gazette on 21 April 1942 (dated 23 April 1942).[16][17]

Manekshaw was evacuated from the battlefield by Sher Singh, his orderly, and took him to an Australian surgeon from the medical team. The surgeon initially declined to treat Manekshaw, saying that he was badly wounded and his chances of survival were very low. But Singh forced him to treat Manekshaw. Meanwhile, Manekshaw regained consciousness, and the surgeon asked what had happened to him, he replied that he was "kicked by a mule". Impressed by Manekshaw's sense of humour, he treated him, and removed seven bullets from his lungs, liver and kidneys. Much of his intestines were removed and stitched.[15] Over Manekshaw's protests to treat the other patients, the regimental medical officer, Captain G. M. Diwan, attended to him.[18][19]

<div class="" style="

background-color: #E0E6F8;

color: Arial;

text-align: center;

font-size: larger;

font-weight: bold;

font size="25";">The Australian surgeon's remark on Manekshaw's reply, when he was asked what happened to him,By Jove, you have a sense of humour. I think you are worth saving.

(Singh 2005, p. 191)

Having recovered from his wounds, Manekshaw attended the 8th Staff Course at Command and Staff College, Quetta, from 23 August to 22 December 1943. He was then posted as the brigade major of the Razmak Brigade, stationed in Burme, serving in that post until 22 October 1944 when he was sent to join the 9th Battalion, 12th Frontier Force Regiment, as part of General William Slim's 14th Army.[15] Towards the end of World War II, after the Japanese surrender, Manekshaw was appointed to supervise the disarmament of over 60,000 Japanese prisoners of war (POWs). He did this with utmost perfection, no cases of indiscipline or escape attempts from the camp were reported. He then went on a six-month lecture tour to Australia in 1946, and after his return was promoted to the rank of lieutenant-colonel, serving as a first grade staff officer in the Military Operations (MO) Directorate.[20]

Post-independence

Upon the Partition of India in 1947, his parent unit – the 4th Battalion of the 12th Frontier Force Regiment – became part of the Pakistan Army, and so Manekshaw was reassigned to the 16th Punjab Regiment. While handling the issues relating to Partition in 1947, Manekshaw demonstrated his sound planning and administrative skills.[21] At the end of 1947, Manekshaw was posted as the commanding officer of the 3rd Battalion of the 5th Gorkha Rifles. But before he moved onto his new appointment, on 22 October, Pakistani forces infiltrated Kashmir, capturing Domel and Muzaffarabad. The following day, the ruler of the princely state of Jammu & Kashmir, Maharaja Hari Singh, appealed for India to send troops. But the Indian government replied that they would send troops only if Jammu and Kashmir acceded and became part of India. On 25 October, V. P. Menon, then-political advisor to the Viceroy of India, along with Manekshaw flew to Srinagar, with the Instrument of Accession. While Menon was with the Maharaja, Manekshaw carried out aerial survey of the situation in Kashmir. After the Maharaja had signed the document, they flew back to Delhi the same night. Soon a briefing was held with Lord Mountbatten, and the Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, where Manekshaw suggested immediate deployments of troops to save Kashmir from being captured.[22]

Though Nehru initially was not in favour of the deployment of troops, he was persuaded by Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, the Deputy Prime Minister. On the morning of 27 October, Indian troops were sent to Kashmir, and Srinagar was saved just in time, right before the Pakistani raiders reached the city outskirts. Maneskhaw's posting order as the commander of the 3rd Battalion of the 5th Gorkha Rifles was cancelled, and he was subsequently posted to the MO Directorate. Incidentally, as a consequence of the Kashmir and annexation of Hyderabad—code named as "Operation Polo", which was also planned by the MO Directorate—, Manekshaw never commanded a battalion. During his term at the MO Directorate, he was promoted to colonel, then brigadier when he was appointed as the Director of Military Operations, becoming the first Indian Director of Military Operations.[22] The appointment of Director of Military Operations was later upgraded to major general and later to lieutenant general and is now termed Director General Military Operations (DGMO).[23]

In April 1952, Maneshaw was appointed as the commander of 167th Infantry Brigade, headquartered at Firozpur. After this, he was appointed as the Director of Military Training at Army Headquarters in April 1954. But he was soon posted as commandant of the Infantry School at Mhow and also became the colonel of both 8 Gorkha Rifles and 61st Cavalry. 8 Gorkha Rifles became his new regiment, since his original parent regiment, the 12th Frontier Force Regiment, had become part of the new Pakistan Army at partition. During his tenure as the commandant of the Infantry School, he discovered that the training manuals were outdated, and was instrumental in revamping the manuals to be consistent with the tactics employed by the Indian Army.[22]

In 1957, he was sent to the Imperial Defence College to attend a higher command course for one year. On his return, he was appointed as the General Officer Commanding (GOC), 26th Infantry Division. While he commanded the division, General K. S. Thimayya was the Chief of the Army Staff (COAS), and Krishna Menon, the Defence Minister. During Menon's visit to Manekshaw's division, he asked what Manekshaw thought of his chief. Manekshaw replied that it was not appropriate for him to think of his chief in that way, and told Menon not to ask anybody again. This annoyed Menon and he told Manekshaw that if he wanted to, he could sack Thimayya, to which Manekshaw replied, "You can get rid of him. But then I will get another." This heated conversation with Menon later proved to be a thorn in his career.[22]

<div class="" style="

background-color: #E0E6F8;

color: Arial;

text-align: center;

font-size: larger;

font-weight: bold;

font size="25";">Manekshaw's reply to Defence Minister Menon, when he inquired what Manekshaw thought of his chief,Mr Minister, I am not allowed to think about him. He is my Chief. Tomorrow, you will be asking my (subordinate) brigadiers and colonels what they think of me. It's the surest way to ruin the discipline of the Army. Don't do it in future.

Major General Sam Manekshaw, GOC, 26 Infantry Division, [24]

In December 1959, Manekshaw was appointed as the commandant of the Defence Services Staff College, Wellington. Soon, he was in middle of an unwanted controversy that almost ended his career. In May 1961, Thimayya resigned as the COAS, and was succeeded by General Pran Nath Thapar. Earlier year, Major General Brij Mohan Kaul was promoted to lieutenant general and appointed as the Quarter Master General (QMG) by Defence Minister Menon against the recommendation of Thimayya. This incident had led to the resignation of Thimayya. Within no time, Kaul was made the Chief of General Staff (CGS), the second highest appointment in Army Headquarters after the COAS. Kaul soon became close to Nehru and Menon, and even more powerful than the chief himself. This was not liked by senior army officials, including Manekshaw. He made a few derogatory comments on the political leadership, which led him to be marked as an anti-national.[22]

Kaul sent informers to spy on Manekshaw, and based on the information gained Manekshaw was charged, and a court of inquiry was ordered. Meanwhile, two of Manekshaw's juniors—Harbaksh Singh and Moti Sagar—were promoted to lieutenant general and appointed as corps commanders. This incident resulted in the widespread implication that Manekshaw had almost been dismissed from the service. The court, presided over by the then-GOC-in-C Western Command, Lieutenant General Daulet Singh, known for his integrity, exonerated Manekshaw. Before a formal 'no case to answer' could be announced, war with China broke out. But due to court proceedings, Manekshaw did not see any notable action during the war. In the war, Indian Army faced a debacle, and many knew that Kaul and Menon were primarily responsible for the failure. Immediately, both were sacked. In November 1962, Nehru asked Manekshaw to take over the command of IV Corps. Manekshaw told Nehru that the action against him was a conspiracy, and that his promotion had been due for almost eighteen months. Nehru apologized, promoted to Manekshaw to lieutenant general and he moved to Tezpur to take over as the GOC IV Corps.[22][25]

Soon after taking charge, Manekshaw found that the reason for the failure in the war with China had been bad leadership. He felt that his foremost responsibility was to improve the morale of the terribly demoralized soldiers, and issued orders to advance to the positions lost in the war, which kept morale up. Just five days in his command, Nehru visited the headquarters with his daughter Indira Gandhi and the COAS, and found the troops advancing. Nehru stated that he didn't want any more men to die. COAS assured him that he would get the orders withdrawn. Manekshaw retorted that the COAS should allow him to command his troops the way he wished or send him to a staff appointment. Gandhi intervened and told Manekshaw to go ahead. Though Gandhi had no official position, she had great influence in the government. The next task Manekshaw took-up was to reorganize the troops in North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA). He took measures to overcome the shortages of equipment, accommodation, and clothing.[26]

A year later, Manekshaw was promoted to the position of army commander and took over Western Command. In 1964, he moved from Shimla to Calcutta as the General Officer Commanding-in-Chief (GOC-in-C) of the Eastern Command.[25][27] As GOC-in-C Eastern Command, he successfully responded to an insurgency in Nagaland for which he was later awarded the Padma Bhushan in 1968.[28][29]

Chief of the Army Staff

Then Chief of the Army Staff (COAS) General P. P. Kumaramangalam was due to retire in June 1969. Though Manekshaw was the most senior commander in army, then Defence Minister Sardar Swaran Singh was in favour of Lieutenant General Harbaksh Singh, who had played a key role as the GOC-in-C of Western Command during the 1965 Indo-Pakistani war. Despite this, Manekshaw was appointed as the 8th Chief of the Army Staff on 8 June 1969.[30] As the Chief of the Army Staff, he developed the Indian Army into an efficient instrument of war.[31] During his tenure as COAS, he was instrumental in stopping the implementation of reservations for scheduled castes and scheduled tribes in the army. Though he was Parsi, a minority group in India, Mankeshaw felt that implementing reservations would comprise the ethos of the army, and also felt all must be given an equal chance.[32]

Indo-Pakistani War of 1971

The Indo-Pakistani conflict was sparked by the Bangladesh Liberation war, a conflict between the traditionally dominant West Pakistanis and the majority East Pakistanis. In 1970, East Pakistanis demanded for autonomy in the state, but the Pakistani government failed to satisfy these demands, and in early 1971, a demand for secession took form in East Pakistan. In March, Pakistan Armed Forces launched fierce campaign to curb the secessionists, including the soldiers and police from East Pakistan. As a result, thousands of East Pakistanis died, and nearly ten million refugees fled to West Bengal, an adjacent Indian state. In April, India decided to assist the formation of new nation of Bangladesh.[33]

Towards the end of April, Indira Gandhi, the Prime Minister, during a cabinet meeting, asked Manekshaw if he was prepared to go to war with Pakistan. In response, Manekshaw told her that most of his armoured and infantry divisions were deployed elsewhere, that only 12 of his tanks were combat-ready, and that they would be competing for rail carriage with the grain harvest at that point of time. He also pointed out that the Himalayan passes would soon open up, with the forthcoming monsoon in East Pakistan, which would result in heavy flooding.[18] When Gandhi asked the cabinet to leave the room and Manekshaw to stay, he offered to resign. She declined to accept it, but sought his advice. He then said he could guarantee victory if she would allow him to prepare for the conflict on his terms, and set a date for it, and Gandhi agreed.[34][35]

As per the strategy planned by Manekshaw, the army launched several preparatory operations in East Pakistan including training and equipping the Mukti Bahini (a local group of Bengali nationalists), and about three brigades of regular Bangladesh troops were trained. As an additional measure, 75,000 guerrillas were trained and equipped with arms and ammunition. These forces were used to sporadically harass the Pakistani Army stationed in East Pakistan in the lead up to the war.[36]

The war started officially on 3 December 1971, when Pakistani aircraft bombed Indian Air Force bases in the western part of the country. The Army Headquarters under the leadership Manekshaw formulated a strategy is as follows: the II Corps, commanded by Lieutenant General Tapishwar Narain Raina (later General, and COAS), was enter from the west; the IV Corps, commanded Lieutenant General Sagat Singh, was enter from the west; the XXXIII Corps, commanded by Lieutenant General M. L. Thapan was enter from the west; additionally the 101 Communication Zone Area, commanded by Major General Gurbax Singh, was provide support from the northeast. This strategy was to be executed by the Eastern Command, under Lieutenant General Jagjit Singh Aurora. Manekshaw instructed Lieutenant General J. F. R. Jacob, Chief of Staff Eastern Command, to inform the Indian prime minister that orders were being issued for the movement of troops from Eastern Command. The following day, the navy and the air force also initiated full-scale operations on both eastern and western fronts.[37]

As the war progressed, Pakistan's resistance crumbled. India captured most of the advantageous positions and isolated the Pakistani forces. Suddenly, the Pakistanis started to surrender or withdraw.[38] The UN Security Council assembled on 4 December 1971 to discuss the hostilities in South Asia. After lengthy discussions on 7 December, the United States made a resolution for "immediate cease-fire and withdrawal of troops". While supported by the majority, the USSR vetoed the resolution twice. In light of the Pakistani atrocities against Bengalis, the United Kingdom and France abstained on the resolution.[39]

Manekshaw addressed the Pakistani troops three times via radio messages on the subject of surrender, assuring them that they would receive honourable treatment from the Indian troops. The messages were broadcast on 9, 11 and 15 December. The last two messages were delivered as replies to the messages from Major General Rao Farman Ali and Lieutenant General Amir Abdullah Khan Niazi. These messages from the Pakistani commanders to their troops were to have a devastating effect on their side, subsequently leading to their defeat. They convinced the troops of the pointlessness of further resistance.[38]

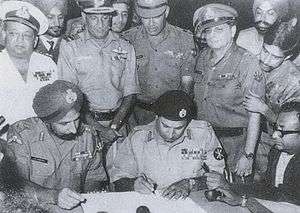

On 11 December, Ali messaged the United Nations requesting a cease-fire, but it was not authorized by the President Yahya Khan and the fighting continued. Following several discussions and consultations, and subsequent attacks by the Indian forces, Khan decided to stop the war in order to save the lives of Pakistani soldiers.[38] The actual decision to surrender was taken by Niazi on 15 December and was conveyed to Manekshaw through the United States Consul General in Dhaka (then Dacca) via Washington. But Manekshaw replied that he would stop the war only if the Pakistani troops surrendered to their Indian counterparts by 9:00 a.m. on 16 December. Later the deadline was extended to 3:00 p.m. of the same day on Niazi's request. The Instrument of Surrender was formally signed on 16 December 1971.[40]

<div class="" style="

background-color: #E0E6F8;

color: Arial;

text-align: center;

font-size: larger;

font-weight: bold;

font size="25";">Manekshaw's first radio message to the Pakistani troops on 9 December 1971,Indian forces have surrounded you. Your Air Force is destroyed. You have no hope of any help from them. Chittagong, Chalna and Mangla ports are blocked. Nobody can reach you from the sea. Your fate is sealed. The Mukti Bahini and the people are all prepared to take revenge for the atrocities and cruelties you have committed....... Why waste lives? Don't you want to go home and be with your children? Do not lose time; there is no disgrace in laying down your arms to a soldier. We will give you the treatment befitting a soldier.

(Singh 2005, p. 209)

When the prime minister asked Manekshaw to go to Dhaka and accept the surrender of Pakistani forces, he declined, saying that the honour should go to the Indian Army Commander in the East, Lieutenant General Jagjit Singh Aurora.[41] Concerned about maintaining discipline in the aftermath of the conflict, Manekshaw issued strict instructions forbidding loot and rape. He stressed the need to respect and stay away from women wherever he went. As a result, according to Singh, cases of loot and rape were negligible.[42] In addressing his troops on the matter, Manekshaw was quoted as saying:

When you see a Begum (Muslim woman), keep your hands in your pockets, and think of Sam.— General Sam Manekshaw, COAS.[42]

The war, lasting under a fortnight, saw more than 90,000 Pakistani soldiers personnel taken as prisoners of war (POWs), and it ended with the unconditional surrender of Pakistan's eastern half, resulting in the birth of Bangladesh as a new nation.[43] Apart from the POWs, Pakistan lost six thousand men, while India lost two thousand.[44] After the war, Manekshaw was known for his compassion towards the POWs. Singh recounts that in some cases he addressed POWs personally, talking to them privately with just his aide-de-camp in his company while they shared a cup of tea. He ensured that POWs were well treated by the Indian Army, making provisions for them to be supplied with the copies of the Quran, and allowing them to celebrate festivals, and to receive letters and parcels from their loved ones.[43]

Promotion to field marshal

After the end of the war, Gandhi decided to promote Manekshaw to the rank of field marshal and subsequently appoint him as the Chief of the Defence Staff (CDS). However, after several objections from the bureaucracy and the commanders of the navy and the air force, the latter was dropped. It was felt that, as Manekshaw was from the army, the comparatively smaller forces as navy and air force would be neglected. Moreover bureaucrats felt that it might challenge their influence over defence issues.[45] Though Manekshaw was to retire in June 1972, his term was extended by a period of six months. On 3 January 1973, Manekshaw was conferred with the rank of field marshal at a ceremony held at Rashtrapati Bhavan. He was the first Indian army officer to be promoted to the rank.[46]

Honours and post-retirement

For his service to the Indian nation, the President of India awarded Manekshaw a Padma Vibhushan in 1972 and conferred upon him the rank of field marshal, a first, on 3 January 1973. He became one of the only two army generals of independent India to be awarded this rank; the other being Kodandera Madappa Cariappa who was awarded the rank in 1986. Manekshaw retired from active service a fortnight later on 15 January 1973 after a career of nearly four decades; he settled down with his wife Silloo in Coonoor, the civilian town next to Wellington Military Cantonment where he had served as commandant of the Defence Services Staff College, at an earlier time in his career. Popular with Gurkha soldiers, Nepal fêted Manekshaw as an honorary general of the Nepalese Army in 1972.[47]

Following his service in the Indian Army, Manekshaw successfully served as an independent director on the board of several companies, and in a few cases, as the chairman. He was outspoken and hardly politically correct, and when once he was replaced on the board of a company by a man named Naik at the behest of the government, Manekshaw quipped, "This is the first time in history when a Naik (corporal) has replaced a Field Marshal."[47]

Controversies

Though Sam Manekshaw was conferred the rank of field marshal in 1973, it was reported that he was never given the complete allowances that were entitled to a field marshal. It was not until President A. P. J. Abdul Kalam took the initiative when he met Manekshaw in Wellington, and made sure that the field marshal was presented with a cheque for Rs 1.3 crores that Manekshaw received his arrears of pay for over 30 years.[48][49]

In May 2007, Gohar Ayub, the son of Pakistani Field Marshal Ayub Khan, claimed that Manekshaw had sold Indian Army secrets to Pakistan during the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965 for 20,000 rupees, but his accusations were dismissed by the Indian defence establishment.[50][51]

Once on being asked by a journalist, he said that his favourite city was London, and in another instance, said that Mohammed Ali Jinnah had asked him to join the Pakistan Army during partition in 1947, and mentioned that if he had joined the Pakistan Army, then India would have been defeated in the 1971 war. The latter remark attracted as much criticism as anything else in his career.[52]

Lieutenant General Jacob, Chief of the Staff of Eastern Command during 1971 war, in his autobiography—An Odyssey in War and Peace—mentioned that Manekshaw gained popularity just because of the media, and claims that he had no battle experience other than the one during Burma Campaign in 1942. Jacob described Manekshaw as "anti-national; anti-government; anti-Semetic". Jacob also mentioned that when Manekshaw was the chief, over a phone call, he mentioned that he had had very little confidence in Lieutenant General Aurora (officiated GOC-in-C of Eastern Command), and on being asked why he was appointing Aurora to the position, allegedly Manekshaw replied, "I like to have him as a doormat." However, according to journalist and former military officer, Ajai Shukla, it is claimed that Jacob had a habit of bracing up his reputation by tarnishing others on false claims.[53]

Personal life

On 22 April 1939, Manekshaw married Siloo Bode in Bombay. The couple had two daughters, Sherry and Maya (later Maja), born on 11 January 1940 and 24 September 1945 respectively. Sherry was married to Batliwala and they have a daughter named Brandy. Maja was employed by the British Airways as a stewardess. She later married Daruwala, a pilot. The couple have two sons named Raoul Sam and Jehan Sam.[54]

Death and legacy

Manekshaw died of complications from pneumonia at the Military Hospital in Wellington, Tamil Nadu, at 12:30 a.m. on 27 June 2008 at the age of 94.[55] Reportedly, his last words were "I'm okay!"[18] He was laid to rest at the Parsi cemetery in Ootacamund (Ooty), Tamil Nadu,[56] with military honours, adjacent to his wife's grave. He was survived by two daughters and three grandchildren.[54] However, neither the President nor the PM or other leaders from the political class turned up at his funeral,[57][58] nor was a national day of mourning declared.[59]

Annually, on 16 December, "Vijay Diwas" is celebrated in memory of the victory achieved under Manekshaw's leadership in 1971. On 16 December 2008, a postage stamp depicting Manekshaw in his field marshal's uniform was released by then President Pratibha Patil.[60] In 2014, a granite statue was erected in his honour at Wellington, in the Nilgiris district, close to the Manekshaw Bridge on the Ooty–Coonoor road,[56] which had been named after him in 2009.[61]

Awards and decorations

| |

| Padma Vibhushan | Padma Bhushan | Poorvi Star | General Service Medal 1947 | [62] |

| Paschimi Star | Raksha Medal | Sangram Medal | Sainya Seva Medal | |

| Indian Independence Medal | 25th Independence Anniversary Medal | 20 Years Long Service Medal | 9 Years Long Service Medal | |

| Military Cross | Burma Star | War Medal | India Service Medal |

See also

Notes

Footnotes

- ↑ Indian military five-star rank officers hold their rank for life, and are considered to be serving officers until their deaths.[1]

- ↑ There were 40 vacancies, of which 15 were filled through open competition, 15 from the army and remaining 10 from the state forces.[7]

Citations

- ↑ Anwesha Madhukalya. "Did You Know That Only 3 People Have Been Given The Highest Ranks In The Indian Armed Forces?". Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ↑ Singh 2005, p. 183.

- 1 2 3 Singh 2005, p. 184.

- ↑ Sharma 2007, p. 59.

- ↑ "Face-to-face with Sam Manekshaw". IBN Live. 28 June 2008. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- 1 2 Singh 2005, p. 185.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Singh 2005, p. 186.

- ↑ Singh 2005, pp. 188–189.

- ↑ Singh 2002, pp. 237–259.

- ↑ Saighal, Vinod (30 June 2008). "Field Marshal Sam Manekshaw". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- ↑ Tarun. "Saluting Sam Bahadur". Retrieved 8 July 2008.

- ↑ Singh 2005, p. 190.

- 1 2 Compton Mackenzie (1951), Eastern Epic, Chatto & Windus, London, pp. 440–1

- ↑ Sam Bahadur: A soldier's general, Times of India, 27 June 2008. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- 1 2 3 Singh 2005, p. 191.

- ↑ London Gazette, Issue 35532, pg 1797 (date 21 April 1942). Accessed on 3 June 2011.

- ↑ Recommendations for Honours and Awards (Army)—Image details—Manekshaw, Sam Hormuzji Franji Jamshadji, Documents online, The National Archives (fee required to view pdf of original citation). Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- 1 2 3 "Obituary: Sam Manekshaw". The Economist (5 July 2008): 107. Retrieved 7 July 2008.

- ↑ Tarun (2008), p. 2

- ↑ Singh 2005, p. 192.

- ↑ "'Jawaharlal, do you want Kashmir, or do you want to give it away?'". Kashmir Sentinel. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Singh 2005, pp. 193–197.

- ↑ Singh 2002, p. 8.

- ↑ "Krishna Menon wanted to sack Manekshaw". Sunday Guardian. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- 1 2 Singh 2002, p. 10.

- ↑ Singh 2005, p. 199.

- ↑ Singh 2002, p. 9.

- ↑ Singh 2002, p. 16.

- ↑ Sharma 2007, p. 60.

- ↑ Singh 2005, p. 201.

- ↑ "Manekshaw". Indianarmy.nic.in.

- ↑ Singh 2005, p. 213.

- ↑ "Indo-Pakistani War of 1971". Global Security. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- ↑ Singh 2005, pp. 204–205.

- ↑ Manekshaw, SHFJ. (11 Nov 1998). "Lecture at Defence Services Staff College on Leadership and Discipline" (Appendix V) in Singh (2002) Field Marshal Sam Manekshaw, M.C. – Soldiering with Dignity.

- ↑ Singh 2005, p. 206.

- ↑ Singh 2005, p. 207.

- 1 2 3 Singh 2005, p. 208.

- ↑ "The World: India and Pakistan: Over the Edge". Time. December 13, 1971. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- ↑ Singh 2005, p. 209.

- ↑ "Field Marshal Sam Manekshaw dead". ibnlive.in.com.

- 1 2 Singh 2005, p. 210.

- 1 2 Singh 2005, pp. 210–211.

- ↑ Colonel Anil Athale (12 December 2011). "Three Indian blunders in the 1971 war". Rediff. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- ↑ Singh 2005, pp. 214–215.

- ↑ Singh 2005, p. 215.

- 1 2 Mehta, Ashok (27 Jan 2003). "Play It Again, Sam: A tribute to the man whose wit was as astounding as his military skill". Outlook. Retrieved 15 Aug 2012.

- ↑ Lt Gen Sk Sinha. "The Making of a Field Marshal". Indian Defence Review. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ↑ Nitin Gokhale (April 3, 2014). "Remembering Sam Manekshaw, India's greatest general, on his birth centenary". NDTV. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ↑ PTI (3 June 2005). "1965 war-plan-seller a DGMO: Gohar Khan". The Times of India (website). Bennett, Coleman & Co. Retrieved 20 May 2011.

- ↑ PTI (8 May 2007). "Military livid at Pak slur on Sam Bahadur". The Times of India (website). Bennett, Coleman & Co. Retrieved 20 May 2011.

- ↑ "Play It Again, Sam". Outlook India. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- ↑ Ajai Shukla (15 June 2011). "History according to Jake". Business Standard India. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- 1 2 Singh 2005, p. 189.

- ↑ Pandya, Haresh (30 June 2008). "Sam H.F.J. Manekshaw Dies at 94; Key to India's Victory in 1971 War". New York Times. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- 1 2 Thiagarajan, Shanta (3 April 2014). "Field Marshal Sam Manekshaw statue unveiled on Ooty–Coonoor road". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014.

- ↑ Pandit, Rajat (28 June 2008). "Lone minister represents govt at Manekshaw's funeral". Times of India. Retrieved 15 Aug 2012.

- ↑ "NRIs irked by poor Manekshaw farewell". DNA – India: Daily News & Analysis. 7 July 2008. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- ↑ "No national mourning for Manekshaw". The Indian Express. 29 June 2008. Retrieved 15 Aug 2012.

- ↑ IANS (18 Dec 2008). "Stamp on Manekshaw released". The Hindu (website). The Hindu group. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- ↑ "Manekshaw Bridge thrown open to traffic". The Hindu. 10 March 2009. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014.

- ↑ Sharma 2007, p. 61.

References

- Singh, Depinder (2002), Field Marshal Sam Manekshaw, M.C.: Soldiering with Dignity, Natraj Publishers, ISBN 978-81-85019-02-4

- Singh, Vijay Kumar (2005), Leadership in the Indian Army: Biographies of Twelve Soldiers, SAGE, ISBN 978-0-7619-3322-9

- Sharma, Satinder (2007), Services Chiefs of India, Northern Book Centre, ISBN 978-81-7211-162-5

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sam Manekshaw. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Sam Manekshaw |

| Military offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Daulet Singh |

General Officer Commanding-in-Chief of the Western Command 1963–1964 |

Succeeded by Harbaksh Singh |

| Preceded by P P Kumaramangalam |

General Officer Commanding-in-Chief of the Eastern Command 1964–1969 |

Succeeded by Jagjit Singh Aurora |

| Preceded by P P Kumaramangalam |

Chief of Army Staff 1969–1973 |

Succeeded by Gopal Gurunath Bewoor |