Mantellodon

| Mantellodon Temporal range: Early Cretaceous, Early Aptian | |

|---|---|

| |

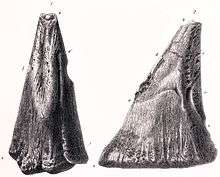

| Lithograph of the type specimen | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Order: | †Ornithischia |

| Suborder: | †Ornithopoda |

| Clade: | †Styracosterna |

| Genus: | †Mantellodon Paul, 2012 |

| Species | |

| |

Mantellodon (meaning "Gideon Mantell's tooth") is a genus of styracosternan ornithopod. The type species is Mantellodon carpenteri. The holotype specimen is NHMUK R3741 consisting of a partial associated postcranial skeleton.[1] It was formerly referred to Iguanodon.

History

The type specimen of M. carpenteri was discovered in a quarry in Maidstone, Kent, owned by William Harding Benstead, in February 1834 (lower Lower Greensand Formation). In June 1834 it was acquired for £ 25 by scientist Gideon Mantell.[2] He was led to identify it as an Iguanodon based on its distinctive teeth. The Maidstone slab was utilized in the first skeletal reconstructions and artistic renderings of Iguanodon, but due to its incompleteness, Mantell made some mistakes, the most famous of which was the placement of what he thought was a horn on the nose.[3] The discovery of much better specimens of Iguanodon bernissartensis in later years revealed that the horn was actually a modified thumb. Still encased in rock, the Maidstone skeleton is currently displayed at the Natural History Museum in London. The borough of Maidstone commemorated this find by adding an Iguanodon as a supporter to their coat of arms in 1949.[4] This specimen has become linked with the name I. mantelli, a species named in 1832 by Christian Erich Hermann von Meyer in place of I. anglicus, but it actually comes from a different formation than the original I. mantelli/I. anglicus material.[5] The Maidstone specimen, also known as Gideon Mantell's "Mantel-piece", and formally labelled NHMUK 3741[1][6] was subsequently excluded from Iguanodon. It is classified as cf. Mantellisaurus by McDonald (2012);[7] as cf. Mantellisaurus atherfieldensis by Norman (2012);[6] and made the holotype of a separate genus and species Mantellodon carpenteri by Gregory S. Paul (2012). The generic name combines Mantell's name with a Greek odon, "tooth", analogous to Iguanodon. The specific name honours Kenneth Carpenter for his work on dinosaurs in general and iguandonts in particular.[1]

Shortly after the discovery, tension began to build between Mantell and Richard Owen, an ambitious scientist with much better funding and society connections in the turbulent worlds of Reform Act–era British politics and science. Owen, at the time a firm creationist, opposed the early versions of evolutionary science ("transmutationism") then being debated and used what he would soon coin as dinosaurs as a weapon in this conflict. With the paper describing Dinosauria, he scaled down dinosaurs from lengths of over 61 metres (200 ft), determined that they were not simply giant lizards, and put forward that they were advanced and mammal-like, characteristics given to them by God; according to the understanding of the time, they could not have been "transmuted" from reptiles to mammal-like creatures.[8][9]

In 1849, a few years before his death in 1852, Mantell realised that the genus today known as Mantellodon was not a heavy, pachyderm-like animal,[10] as Owen was putting forward, but had slender forelimbs; however, his passing left him unable to participate in the creation of the Crystal Palace dinosaur sculptures, and so Owen's vision of the dinosaurs became that seen by the public for decades.[8] With Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, Owen had nearly two dozen lifesize sculptures of various prehistoric animals built out of concrete sculpted over a steel and brick framework; two Mantellodon, one standing and one resting on its belly, were included. Before the sculpture of the standing Mantellodon was completed, a banquet for twenty was held inside it.[11][12][13]

Description

Paul (2012, p. 125) provided a short diagnosis of Mantellodon: "Dentary straight, elongated diastema present, dentary shallow ventral to diastema and deeper astride dentary battery, anteriormost dentary teeth reduced. Forelimb robust, olecranon process well developed, some carpals very large, metacarpals fairly elongated, thumb spike massive."

David Bruce Norman in 2013, considered Paul's description of Mantellodon to be inadequate, identical to that given by Paul of Darwinsaurus and entirely incorrect, noting that no dentary is preserved in the holotype specimen, and that the preserved forelimb elements "are gracile, carpals are not preserved, the metacarpals are elongate and slender, and a thumb spike is not preserved". Norman considered the holotype specimen of Mantellodon carpenteri to be referable to the species Mantellisaurus atherfieldensis.[14]

In popular culture

Two lifesize reconstructions of Mantellodon (considered Iguanodon at the time) built at the Crystal Palace in London in 1852 greatly contributed to the popularity of the animal.[15] Their thumb spikes were mistaken for horns, and they were depicted as elephant-like quadrupeds, yet this was the first time an attempt was made at constructing full-size dinosaur models.

References

- 1 2 3 Gregory S. Paul (2012). "Notes on the rising diversity of iguanodont taxa, and iguanodonts named after Darwin, Huxley and evolutionary science" (PDF). Actas de V Jornadas Internacionales sobre Paleontologia de Dinosaurios y su Entorno, Salas de los Infantes, Burgos. Colectivo Arqeologico-Paleontologico de Salas de los Infantes (Burgos). pp. 121–131.

- ↑ Norman, D.B., 1993, "Gideon Mantell’s “Mantel-piece”: the earliest well-preserved ornithischian dinosaur", Modern Geology 18: 225-245

- ↑ Mantell, Gideon A. (1834). "Discovery of the bones of the Iguanodon in a quarry of Kentish Rag (a limestone belonging to the Lower Greensand Formation) near Maidstone, Kent". Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal. 17: 200–201.

- ↑ Colbert, Edwin H. (1968). Men and Dinosaurs: The Search in Field and Laboratory. New York: Dutton & Company. ISBN 0-14-021288-4.

- ↑ Olshevsky, G. "Re: Hello and a question about Iguanodon mantelli (long)". Retrieved 2007-02-11.

- 1 2 David B. Norman (2012). "Iguanodontian taxa (Dinosauria: Ornithischia) from the Lower Cretaceous of England and Belgium". In Godefroit, P. (eds). Bernissart Dinosaurs and Early Cretaceous Terrestrial Ecosystems. Indiana University Press. pp. 175–212. ISBN 978-0-253-35721-2.

- ↑ McDonald, Andrew T. (2012). "The status of Dollodon and other basal iguanodonts (Dinosauria: Ornithischia) from the upper Wealden beds (Lower Cretaceous) of Europe". Cretaceous Research. 33 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2011.03.002.

- 1 2 Torrens, Hugh. "Politics and Paleontology". The Complete Dinosaur, 175–190.

- ↑ Owen, R. (1842). "Report on British Fossil Reptiles: Part II". Report of the British Association for the Advancement of Science for 1841. 1842: 60–204.

- ↑ Mantell, Gideon A. (1851). Petrifications and their teachings: or, a handbook to the gallery of organic remains of the British Museum. London: H. G. Bohn. OCLC 8415138.

- ↑ Benton, Michael S. (2000). "brief history of dinosaur paleontology". In Gregory S. Paul (ed.). The Scientific American Book of Dinosaurs. New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 10–44. ISBN 0-312-26226-4.

- ↑ Yanni, Carla (September 1996). "Divine Display or Secular Science: Defining Nature at the Natural History Museum in London". The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 55 (3): 276–299. doi:10.2307/991149. JSTOR 991149.

- ↑ Norman, David B. The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. p. 11.

- ↑ David B. Norman (2013). "On the taxonomy and diversity of Wealden iguanodontian dinosaurs (Ornithischia: Ornithopoda)" (PDF). Revue de Paléobiologie, Genève. 32 (2): 385–404.

- ↑ Smith, Dan (2001-02-26). "A site for saur eyes". New Statesman. Retrieved 2007-02-22.