Marc Bauer

| Marc Bauer | |

|---|---|

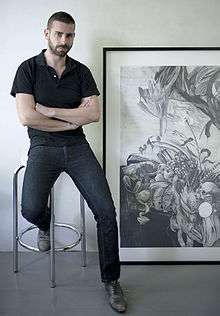

Marc Bauer in his Berlin studio October 2012 | |

| Born |

May 28, 1975 Geneva, Switzerland |

| Nationality | Swiss |

| Education |

2002-2004 Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten, Amsterdam 1995-1999 Ecole Supérieure d’Art Visuel, Geneva |

| Known for | Drawing, Installation art, Animation |

Marc Bauer (born May 28, 1975, Geneva, Switzerland) is an artist best known for his works in the graphic medium, primarily drawing.

Life and career

Bauer studied at the Ecole supérieure d’art visuel (now HEAD) in Geneva and the Rijksakademie van beeldende kunsten, in Amsterdam. He lives and works in Berlin and Zurich. His work has featured in numerous group shows, including at the Centre Pompidou and Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst, and in many solo exhibitions, including at the Kunstmuseum St. Gallen, Centre Culturel Suisse, Paris, and the Frac Auvergne.

Work

Style and technique

Bauer’s graphic work is rendered almost exclusively in black-and-white, a pared-down aesthetic that seems deliberately evocative of old photographs. In scale, his graphic work varies widely, from small works on paper to large-scale images comprising several sheets pieced together, to digital prints made of blow-ups of his drawings, and even enormous wall drawings, rendered directly on the wall. Other supports for his work have included ceramic vases and coated Dibond aluminium panels. Bauer often produces works in series, and his exhibitions are usually conceived as site-specific installations that address the exhibition space as a larger composition. These installations frequently include a non-hierarchical arrangement of drawings – mostly unframed – pinned onto the walls, as well as drawings (often studies for the larger works) sometimes presented in specimen display cases to be viewed from above, textual accompaniments (sometimes even drawings of handwritten material such as letters), projections of earlier graphic works, objects (usually ones featured in a drawing), and large graphic murals made on the gallery’s walls expressly for the show, which often add an illusionistic element to the overall display.

Notably, Bauer’s installations also often feature drawings from earlier series, and this “recycling” leads to their ongoing re-contextualization and serves to underscore long-running themes that are then presented in a new, sometimes topical light. A good example of this is Bauer’s continual (possibly even anachronistic) exploration of the theme of fascism, viewed most recently from the perspective of the Gurlitt case and the Nazi’s “Degenerate Art” campaign.

Visually, Bauer’s works are typically dark in tone and the contours of his figures are often blurred, through his practice of using a hard thin eraser to rub away and smear the graphite and lithographic chalk and to achieve a sense of depth. This blurring effect partly gives Bauer’s drawings their distinctive “look” and also subverts the traditional concept of the line as the defining element in the art of drawing, as in some works – especially his landscapes or images of deserted cinemas and swimming pools – the dense application and distribution of the graphite has, at first glance, a paint-like, textured appearance. This effect culminates in the technique deployed in Bauer’s animated film The Architect, in which the application of a oil paint on Plexiglas is captured in thousands of stop-motion images and even becomes a narrative element in itself which propels the story forward.

The blurring created through the repeated erasure and addition of more pencil simulates the process of remembering and forgetting that lies at the heart of Bauer’s artistic endeavour, and which is encapsulated in his statement “in order to remember, you need to forget first”.[1] The smudging of contour also echoes techniques traditionally associated with painting, such as sfumato[2] and shows Bauer entering into a centuries-old discourse within the history of art about the possibilities of his chosen medium, contested here not necessarily against the art of painting, but against the supposed sharpness, objectivity, and dominance of the photographic image.

Subject matter

A key recurring theme in Bauer’s art is history and memory – the personal and the collective – which he presents as closely intertwined. Some of his earliest works on paper drew from childhood memories and snapshots from family albums, featuring images of his own relations (as in the 2007 “A viso aperto” sequence from the artist’s book History of Masculinity[3]). These were interspersed with images of historical figures from the time, such as Mussolini and Hitler. Through this juxtaposition, the power relations in the family images were infused with broader power dynamics at play among the general populace under fascism.

Over the course of his oeuvre, Bauer’s investigation of history and historiography has evolved from the primarily personal (as in “A viso aperto”) to broader social and political histories (e.g. Monument, Roman-Odessa[4] and The will of desire[5]) and increasingly involves him making archival research into his intended subjects beforehand. For instance, for the group show, Sacré 101 – An Exhibition Based on "The Rite of Spring", Bauer accessed the archives of the Ballets Russes to form his own personal impression of the dancer Vaslav Nijinsky and his suffering of schizophrenia.[6] And in preparation for his show at the Aargauer Kunsthaus in 2014, Bauer’s research into Hildebrand Gurlitt’s involvement in the fate of two works by Karl Ballmer led him to access the archives at the Karl Ballmer Foundation.[7] In both cases, Bauer’s use of the archive, usually a touchstone for objectivity, resulted in a highly subjective perspective on his subject.

The subjective view on a historical topic is also achieved through Bauer’s frequent invention of characters that provide a narrative structure for his series of drawings.[8] These characters are often teenage boys or young men (as in In the Past, Only, Le Quartier, Quimper, and The Architect), whose actions convey a sense of latent violence and repressed (often homoerotic) desires. The narrative element in Bauer’s work is further buoyed up by his repeated appropriation and reworking of well-known films, notably the iconic black-and-white images of silent cinema (Battleship Potemkin in Monument, Roman-Odessa, Nosferatu in The Architect), but also more recent, colour films such as Planet of the Apes, and La Jetée in Fragments of 29 Minutes, 1963. In his use of such sources, Bauer usually selects key images from the film and reworks them as graphically rendered stills. Shown in an elliptical sequence, these series adopt cinematic editing effects that require the spectator to piece together the narrative in their mind, while also tapping into the spectator’s collective consciousness, in a process that “explores the way popular culture constructs its myths and symbols”.[9]

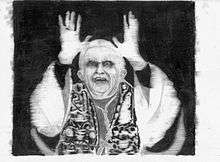

A similar effect is achieved through Bauer’s practice of culling images from historical photographs. These can range from intimate portrait shots (Martin Heidegger in the work Die Grosse Erwartung von M.H.[10]), to school-photograph-like group portraits,[11] and images of famous historical figures such as Pope Benedict XVI or Goebbels. These portrait drawings nearly always bring attention to the fact that they are derived from photographs and that the sitters are conscious of being portrayed. As such, Bauer can be said not only to reference specific photographs, but also the medium of photography itself as means of capturing moments in time. Accordingly, the atmosphere of Bauer’s drawings often convey a characteristic sense of stillness (even when the figures are depicted in motion) and of the images’ “mediatedness”. This exploration of the concept of capturing time is reflected in his recurring interest and depiction of still lifes. By using the medium of drawing, in which each work is the result of a slow process formed by the continual interaction between the eye, mind, and hand, Bauer creates images that are in many ways more “still” than they appear in the photograph on which they are based or if they were shot by camera.

Selected exhibitions

Solo

- 2015 Cinerama, Frac Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur, Marseille

- 2015 Static / Unfolding Time, Deweer Gallery, Otegem

- 2014 Cinerama, Frac Alsace, Sélestat

- 2014 Der Sammler, Museum Folkwang, Essen

- 2014 In the past, only, Le Quartier, Quimper

- 2014 Cinerama, Frac Auvergne, Clermont-Ferrand

- 2013 The Astronaut, Freymond-Guth Fine Arts, Zurich

- 2013 Le Collectionneur, Centre Culturel Suisse, Paris

- 2012 Pleins Pouvoirs, septembre, La Station, Nice

- 2012 Le ravissement mais l'aube, déjà, Musée d'art de Pully, Lausanne. With Sara Masüger

- 2012 Nature as Territory, Kunsthaus Baselland, Muttenz/Basel

- 2011 Totstell-Reflexe, partly with Christine Abbt, Kunstmuseum St. Gallen, St. Gallen

- 2010 Premier conte sur le pouvoir, MAMCO, Geneva

- 2009 LAQUE, Frac Auvergne, Clermont-Ferrand

- 2007 History of Masculinity, attitudes, Geneva

- 2006 Geschichte der Männlichkeit III, o.T. Raum für aktuelle Kunst, Lucerne

- 2005 Overthrowing the King in His Own Mind, with Shahryar Nashat and Alexia Walther, Kunstmuseum Solothurn, Solothurn

- 2004 Tautology, Stedelijk Museum Bureau, Amsterdam

- 2004 Happier Healthier, Store Gallery, London

- 2001 Archeology, attitudes, Geneva

- 2000 Swiss Room, Art-Magazin, Zurich

Group

- 2015 The Bottom Line, S.M.A.K, Ghent. Curated by Martin Germann and Philippe van Cauteren

- 2015 Triennial of Contemporary Prints, Musée des beaux-arts, Le Locle.

- 2015 Europa, Die Zukunft der Geschichte, Kunsthaus Zurich. Curated by Cathérine Hug

- 2015 Drawing Now, Albertina, Vienna. Curated by Elsy Lahner

- 2015 Meeting Point, Kunstverein Konstanz. Curated by Axel Lapp

- 2015 Drawing Biennial, Drawing Room, London

- 2015 Meisterzeichnungen, 100 Jahre Grafische Sammlung, Kunsthaus Zurich

- 2014 Docking Station, Aargauer Kunsthaus, Aarau

- 2014 Liverpool Biennial, curated by Mai Abu ElDahab and Anthony Huberman

- 2014 Sacré 101 – An Exhibition Based on "The Rite of Spring", Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst, Zurich. Curated by Raphael Gygax

- 2013 Donation Florence et Daniel Guerlain, Centre Pompidou, Paris

- 2013 Les Pléiades - 30 ans des FRAC, Les Abattoirs, Toulouse

- 2012 Reality Manifestos, or Can Dialectics Break Bricks?, Kunsthalle Exnergasse, Vienna

- 2011 Le réel est inadmissible, d’ailleurs il n’existe pas, Centre d’Art du Hangar à Bananes, Nantes

- 2011 The Beirut Experience, Beirut Art Center, Beirut

- 2011 In erster Linie, Kunstmuseums Solothurn

- 2010 Voici un dessin Suisse (1990-2010), Musée Rath, Geneva

- 2009 Usages du document, Centre Culturel Suisse, Paris

- 2008 Shifting identities, Kunsthaus, Zurich

- 2004 Fürchte Dich, Helmhaus, Zürich

- 2004 A Molecular History of Everything, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne

- 2003 Durchzug/Draft, Kunsthalle, Zürich

Projects

- 2015 City hospital Triemli, Zurich. Wall drawings

- 2015 Wall drawing in Kaufleuten Zurich

- 2013 Aubusson tapestry in cooperation with Aubusson Tapestry Museum, Melancholia I. Musée de la tapisserie d’Aubusson

- 2013 La Révolte et L'Ennui, curated exhibition with interventions by Marc Bauer. FRAC Auvergne, Clermont-Ferrand

- 2013 The Architect, Animated film, 27 minutes. Cooperation between Marc Bauer who animated the film and wrote the script, and the French music group Kafka who composed and performed the music.

Publications

- The Bottom Line, catalogue. Published by S.M.A.K. Ghent

- Drawing Now, catalogue. Published by Albertina, Vienna

- Triennial of Contemporary Prints, catalogue. Published by the Musée des beaux-arts, Le Locle

- Europa, die Zukunft der Geschichte, catalogue, Published by Kunsthaus Zurich. ISBN 978-3-03810-088-1

- Meisterzeichnungen, 100 Jahre Grafische Sammlung, catalogue. Published by Kunsthaus Zurich. ISBN 978-3-85881-450-0

- The Architect, artists' book. Published by Frac Auvergne, Alsace and Paca, 2014. ISBN 978-2-907672-17-7

- The Collector, artists' book. Published by Centre Culturel Suisse, Paris, 2013. ISBN 978-2-909230-13-9

- Sacré 101 - An Exhibition Based on the Rite of Spring, catalogue. Published by Migros Museum, 2013. ISBN 978-3-03764-368-6

- VITAMIN D2 - New perspectives in drawing, catalogue. Published by Phaidon, London - New York, 2013. ISBN 978-0-7148-6528-7

- Donation Florence et Daniel Guerlain - Dessins contemporains, catalogue. Published by Centre Pompidou, Paris, 2013. ISBN 978-2-84426-625-5

- The Beirut Experience, catalogue. Published by attitudes, Genf. ISBN 978-29-40178-19-3

- MARC BAUER, monographic catalogue. Published by Kehrer, Heidelberg; and Kunstmuseum St.Gallen, 2011. ISBN 978-3-868281-60-6

- STEEL, artist book. Published by FRAC Auvergne, 2009. ISBN 978-2-907672-07-8

- History of masculinity, artist book. Published by attitudes, Geneva, 2007. ISBN 978-2-940178-11-7

- Documents, Marc Bauer: Tautology, writings. Published by Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten, Amsterdam, 2005

- Overthrowing the king in his own mind, catalogue. Published by Kunstmuseum Solothurn and Revolver Editions, 2005. ISBN 978-3-865880-59-8

- Happier Healthier, artist book in cooperation with Vincent van der Marck and Store Gallery, London, 2004

- Across the Great Channel, artist book. Published by Memory Cage editions, Zürich, 2000. ISBN 3-907053-14-1

Prizes

- 2009 Prix culturel Manor, Geneva

- 2006 Swiss Art Awards, Basel

- 2006 Artist residency in Beijing of the GegenwART Foundation, Berne

- 2005 Swiss Art Awards, Basel

- 2005 Swiss Institute residency, Rome

- 2001 Swiss Art Awards, Basel

Public collections

- Aargauer Kunsthaus

- Museum Folkwang, Essen

- Centre Pompidou - Musée National d´Art Moderne, Paris

- Musée d'art de Pully, Lausanne

- Migros museum für gegenwartskunst, Zurich

- Kunstmuseum St. Gallen, St. Gallen

- Kunstmuseum Solothurn, Solothurn

- Kunsthaus, Zurich

- Sturzenegger Stiftung, Museum zu Allerheiligen, Schaffhausen

- FRAC Auvergne, Clermont-Ferrand

- FRAC Alsace, Sélestat

- Museo Cantonale d'Arte, Lugano[12]

External links

- marcbauer.net - Official Website

- Website Deweer Gallery - Marc Bauer

- Current exhibitions at Artfacts.Net

Videos

- Clips of The Architect. Vimeo

- Interview with Marc Bauer and images of the exposition La Révolte et l'Ennui at FRAC Auvergne, July 2013. French

- Review of the exhibition Nature as Territory in Kunsthaus Baselland. Art-TV, May 2012. German

- Artist talk at the occasion of the exhibition Totstell-Reflexe at Kunstmuseum St. Gallen, 2011. German

- Video interview with Marc Bauer by FRAC Auvergne, 2009. French

Interviews

- Interview by Thomas Lapointe for La Revue Entre, 2012. French

- Interview by Laurence Cesa-Mugny for the Swiss Institute for Art Research, October 2009. German

Reviews, articles

- Article in Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung by Julia Voss. Gurlitt und sein Künstlerfreund, September 2, 2014

- Review in Artforum by Riccardo Venturi. Marc Bauer, May 2013

- Article by Benjamin Paul for Artforum. Viewing Distance, January 2011

- Review in Artforum by Valérie Knoll. Gegen mein Gehirn exhibition in Gallerie Elisabeth Kaufmann, 2007

References

- ↑ Allen, Jennifer (2011). "Marc Bauer in conversation with Jennifer Allen". MARC BAUER. Kehrer Verlag and Kunstmuseum St.Gallen. p. 248. ISBN 9783868281606.

- ↑ Paul, Benjamin (January 1, 2011). "Viewing Distance". Artforum. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- ↑ Bauer, Marc (2007). History of Masculinity. Geneva: attitudes. pp. 5–26. ISBN 9782940178117.

- ↑ Bauer, Marc (2009). STEEL. Clermont-Ferrand: Frac Auvergne. ISBN 9782907672078.

- ↑ Bauer, Marc (2007). History of Masculinity. Geneva: attitudes. pp. 27–41. ISBN 9782940178117.

- ↑ Gygax, Raphael. "Sacré 101 – An Exhibition Based on "The Rite of Spring"". www.migrosmuseum.ch. Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ↑ Voss, Julia. "Gurlitt und sein Künstlerfreund". Faz.net. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ↑ Detton, Keren. "Marc Bauer / Dierk Schmidt". www.le-quartier.net. Le Quartier. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ↑ Detton, Keren. "Marc Bauer / Dierk Schmidt". www.le-quartier.net. Le Quartier. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ↑ Bauer, Marc (2007). History of Masculinity. Geneva: attitudes. ISBN 9782940178117.

- ↑ Bauer, Marc (2007). History of Masculinity. Geneva: attitudes. ISBN 9782940178117.

- ↑ Museo Cantonale d'Arte, Lugano: Marc Bauer