Marriage in Australia

As was the case for other western countries marriage in Australia for most of the 20th century was done early and near-universally, particularly in the period after World War II to the early 1970s. Marriage at a young age was most often associated with pregnancy prior to marriage.[1]

Marriage was once seen as necessary for couples who cohabited. While such an experience for some couples did exist, mostly because it is hard to detect, it was relatively uncommon up until the 1950s in much of the western world.[2] If both partners are under the age of 18, marriage in Australia is not permitted. In ‘exceptional circumstances’ the marriage of persons under 18 but over 16 may be authorised by a court.

The official registration of marriage is the responsibility of each state and territory.[3] A Notice of Intended Marriage is required to be lodged with the chosen celebrant.[4]

According to a 2008 Relationships Australia survey love, companionship and signifying a lifelong commitment were the top reasons for marriage.[5]

History

In colonial New South Wales marriage was often an arrangement of convenience. For female convicts marriage was a way of escaping incarceration and land leases were denied to those who were unmarried.[6]

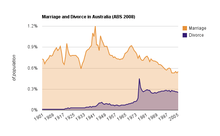

A federal Marriage Act was passed in 1961 which set uniform Australia-wide rules for recognition and solemnisation of marriages. Prior to this Act, the states and territories administered their own marriage laws. The Commonwealth Family Law Act of 1975 made it easier to divorce and removed the concept of fault, requiring only a twelve-month period of partners' separation.[7]

The 1970s saw a significant rise in the divorce rate in Australia.[1] A change in social attitudes from divorce being only acceptable if there were severe problems towards divorce being acceptable if that is the preference of the partners is attributed to this change.[8]

Australia has recognised de facto relationships since the Family Law Act of 2009.

Marriage Amendment Act 2004

The 2014 Marriage Amendment (Celebrant Administration and Fees) Act amended the Marriage Act 1961 in relation to celebrants, and for other purposes.[9]

Social change

The Australian Burearu of Statistics notes that "The proportion of adults living with a partner has declined during the last two decades, from 65% in 1986, to 61% in 2006". The proportion of Australians who are married fell from 62% to 52% over the same period.[10]

Common-law marriage has increased significantly in recent decades from 4% to 9% between 1986 and 2006.[10] It is often a prelude to marriage and reflects the shift to attain financial independence before having children.[11] In 2009, 79.4% of all those married had been cohabitating.[12]

Civil Celebrants Since 1999 Civil celebrants have overseen the majority of marriages. In 2015, 74.9 per cent of all marriages were solemnised by a civil celebrant,.[13]

Attitudes to Women, Marriage and Work The Commonwealth Public Service placed a bar on employment of married women meaning that married women could only be employed as temporary staff. Any female employee was required to resign upon being married. This bar restricted female promotion opportunities. This bar was lifted in 1966.[14]

In 1971, more than three quarters of women surveyed placed being a mother before their career. By 1991 this figure had dropped to just one quarter.[7] By the 1980s the trend towards a delay of first marriage in Australia was evident. In 1989, more than one woman in five had not married by the age of 30.[1]

Divorce in Australia The crude divorce rate was 2.0 divorces per 1,000 estimated resident population in 2014, down from 2.1 in 2013. The median duration from marriage to divorce in 2014 was 12.0 years with a median age at divorce for males was 45.2 years of age and the median age of females was 42.5 years of age.[12]

Same Sex Marriage In 2004, the Marriage Amendment Act defined marriage as the union of a man and a woman to the exclusion of all others, voluntarily entered into for life.[15] Since then there have been 16 attempts to have marriage equality in Australia. The 2011 Census, recorded 33,700 same-sex couples in Australia. 17,600 were male same-sex couples and 16,100 were female same-sex couples. Same-sex couples represented about 1% of all couples in Australia.[16]

Same-sex marriage

Same-sex marriage is not permitted in Australia. Since 2004 there have been 16 attempts to have same-sex marriage legalised.[17] In Australia, marriage is defined under the Marriage Amendment Act in 2004 which reads:

- Marriage means the union of a man and a woman to the exclusion of all others, voluntarily entered into for life.[18]

In 2009, the Australian Government included all de facto couples, including same-sex couples, under the Family Law Act (1975).[19] This allowed de facto and same-sex couples the same property rights as married couples.[20]

Same-sex couples have access to domestic partnership registries in New South Wales, Tasmania, Queensland and Victoria. Civil unions are performed in the Australian Capital Territory.

Those advocating the retention of the existing Marriage Act, have said:

- that marriage has been defined as a heterosexual union "throughout history, transcending time, religions, cultures, and people" and that, "the modern state recognises and regulates marriage because of its importance to the good of society". There are implications for Freedom of religion and Freedom of thought following any legislated change.[21]

- that the institution of marriage involving a woman and a man for the purpose of having children is one of the bedrocks of Australian society and is common across cultures and has existed for generations. There are good reasons as to why it is so enduring.[22]

- that the institution of marriage involving a woman and a man provides health benefits for society.[23]

- that up until now there have been too many, "slogans, emotional spin and almost unprecedented public bullying of opponents" and that, "we should resist being railroaded into this social change too quickly".[24][25] There are, "debates within gay communities" as to, "what sort of marriages do homosexual people want?"[26][27]

- that the word marriage isn’t a label that can transferred to various relationships, as it "has an intrinsic or natural meaning prior to anything we may invent or the state may legislate.[28]

Implications

For adults

Concern has been raised by both Catholic[29] and Anglican church leaders[30] that if same-sex marriage is legislated, there is the probability of restrictions in religious freedom.[31]

Same-sex marriage, with its emphasis on gender neutrality nullifies commonly understood gender pronouns such as husband & wife and bride & groom.[32] Terms such as man & woman and father & mother become "interchangeable social constructs".[33] Similarly, the terms dad & mum[34] and male & female (particularly as reported, a third of transgender people do not identify as male nor female)[35][36] all become valueless.

A spokesman for the Catholic Church has said, "By logic, if marriage can be redefined as not exclusive to a man and woman then that redefinition can apply to any number of unions and relationships."[33] A convenor of the ACT Greens party has said when same-sex marriage is limited to, "two consenting adults [this] discriminates against others in the gay community, including polyamorists". He accused the Australian Greens of being "hypocrites" because the logic they use to argue for marriage equality should extend to people who have multiple partners.[37][38] While Sarah Hanson-Young says that the, "institution of marriage should involve only two consenting adults",[39] Natalie Bennett the Australian born convenor of the Green Party of England and Wales has voiced support for polygamy and polyamorous relationships.[40]

While there have been studies carried out on the children of LGBT parents, with some supporting same-sex parenting,[41] and some not,[42] an American sociologist has stated that it is, "too early for social scientists to make far-reaching conclusions about families headed by same-sex couples".[43]

For children

Some critics or marriage equality have warned that changes to the Marriage Act will have a detrimental effect on children. The Australian Marriage Forum has claimed that children have a birth-right, wherever possible, to both a mother and father, with same-sex marriage being a calculated decision by which a child is forced to miss out on a mother or a father[44] with governments being in the marriage business, "because the union of a man and woman can produce a child and children need a mum and a dad."[45]

Australian Marriage Equality national director, Rodney Croome, responded by stating that “The Australian Marriage Forum campaign is actually harming the many Australian children being raised by same-sex couples because it defends discrimination against their families.”

See also

- Australian Aboriginal kinship

- Australian family law

- Celebrant (Australia)

- Polygamy in Australia

- Recognition of same-sex unions in Australia

- Voidable marriages (Australia)

References

- 1 2 3 McDonald, P. (1992). "The 1980s: Social and Economic Change Affecting Families". In Jagtenberg, Tom; D'Alton, Phillip. Four Dimensional Social Space. Pymble, Sydney: Harper Educational Publishers. pp. 126–128. ISBN 0063121271.

- ↑ Thornton, Arland; William G. Axinn; Yu Xie (2008). Marriage and Cohabitation. University of Chicago Press. p. 72. ISBN 0226798682. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- ↑ "Births, deaths and marriages – Fact sheet 89". National Archives of Australia. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- ↑ "Your Legal Obligations". Australian Marriage Celebrants. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- ↑ "Why do people get married?". Relationships Australia. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- ↑ Edgar, Don (2012). Men Mateship Marriage. HarperCollins Australia. ISBN 0730496589. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- 1 2 Clancy, Laurie (2004). Culture and Customs of Australia. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 57–58. ISBN 0313321698. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- ↑ Halford, W. Kim (2011). Marriage and Relationship Education: What Works and How to Provide It. Guilford Press. p. 13. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- ↑ https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2014A00025

- 1 2 http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/[email protected]/Lookup/4102.0Main+Features20March%202009

- ↑ Uhlmann, Allon J. (2006). Family, Gender and Kinship in Australia: The Social and Cultural Logic of Practice and Subjectivity. Ashgate Publishing. p. 31. ISBN 0754680266. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- 1 2 http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/mf/3310.0

- ↑ "Marriages and Divorces, Australia, 2015". Australian Bureau of Statistics. ABS. 30 Nov 2015. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- ↑ http://timeline.awava.org.au/archives/264

- ↑ "Marriage Amendment Act 2004". comlaw.gov.au.

- ↑ http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/[email protected]/Lookup/4102.0Main+Features10July+2013

- ↑ "Cory Bernardi and Penny Wong debate same-sex marriage at National Press Club". NewsComAu.

- ↑ "Marriage Amendment Act 2004". comlaw.gov.au.

- ↑ "The History Of Family Law In Australia |". historycooperative.org. Retrieved 2016-09-23.

- ↑ "FAMILY LAW ACT 1975 - SECT 4AA De facto relationships". www.austlii.edu.au. Retrieved 2016-09-23.

- ↑ "Submission 147 to the Legal and Constitutional Affairs Legislation Committee, Concerning the Marriage Equality Amendment Bill 2010". Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Legislation Committee. 4 May 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ↑ Donnelly, Kevin (12 August 2015). "Abbott made the right call on same-sex marriage". ABC, The Drum. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ↑ "Gay marriage a health risk, says doctors' group".

- ↑ Fisher, Anthony (24 July 2015). "Same-Sex 'Marriage': Evolution or Deconstruction of Marriage and the Family? (Edited version)". ABC Religion and Ethics. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ↑ Fisher, Anthony (22 July 2015). "Same-Sex 'Marriage': Evolution or Deconstruction of Marriage and the Family?". Catholic Archdiocese of Sydney. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ↑ Sandeman, John (29 June 2012). "What sort of marriages do homosexual people want". Bible Society. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ↑ Mitchell, Natasha (11 June 2012). "Why get married when you could be happy?". ABC News. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ↑ "'Same-sex' Marriage Pastoral Letter: Don't Mess With Marriage". Australian Catholic Bishops Conference. 2015. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ↑ Howden, Saffron (16 October 2015). "Churches' fight against gay marriage gains momentum". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ↑ Howden, Saffron (12 October 2015). "Sydney Anglican Archbishop Glenn Davies' call to arms over same-sex marriage". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ↑ Howden, Saffron (14 October 2015). "Democracy tested by same sex-marriage plebiscite, Archbishop Anthony Fisher warns". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ↑ Jensen, Peter (29 August 2012). "Men and women are different, and so should be their marriage vows". The Australian. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- 1 2 McDougall, Bruce (17 June 2015). "Catholic bishops' explosive warning of three-way unions if marriage changes go ahead". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ↑ Fisher, Anthony (20 May 2015). "Same-sex marriage undermines purpose of the institution". The Australian. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ↑ Lauder, Simon (5 May 2015). "Mx flagged as possible title for transgender and other gender neutral people, according to Oxford English Dictionary". ABC News. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ↑ Glicksman, Eve (April 2013). "Transgender terminology: It's complicated". Vol 44, No. 4: American Psychological Association. p. 39. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

Use whatever name and gender pronoun the person prefers

- ↑ Copland, Simon (14 June 2012). "We need to return to our liberation roots". Str Observer. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ↑ Higgins, Ean (17 July 2012). "Greens 'elitist' on wedlock". The Australian. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ↑ Moynihan, Carolyn (5 June 2012). ""Me too" say Aussie polyamorists". Mercatornet. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ↑ Duffy, Nick (20 October 2015). "Green Party wants every teacher to be trained to teach LGBTIQ issues". Pink News. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ↑ Dempsey, Deborah (18 December 2013). "Same-sex parented families in Australia". Australian Institute of Family Studies. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ↑ Sullins, Paul (21 January 2015). "Child Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in Same-Sex Parent Families in the United States: Prevalence and Comorbidities". British Journal of Medicine & Medical Research. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ↑ White, Ed (4 March 2014). "Disputed study's author testifies on gay marriage". Washington Times. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ↑ van Gend, David (8 May 2014). "Repudiating the calculated decision to deprive children of mothers". MercatorNet. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- ↑ Moynihan, Carolyn (3 April 2014). "It doesn't come much clearer than this". MercatorNet. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Marriage in Australia. |

- Getting married - Government information

- Births, deaths and marriages registries - Government information