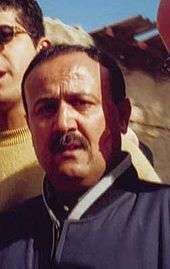

Marwan Barghouti

| Marwan Barghouti | |

|---|---|

| |

| Palestinian Legislative Council member[1] | |

|

In office 1996[1] – present | |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

6 June 1959 Kobar,[1] West Bank of Jordan |

| Nationality | Palestinian[1] |

| Political party |

Fatah (1974–2005, 2006–present)[1] Al-Mustaqbal (2005–2006) |

| Spouse(s) | Fadwa Barghouti |

| Religion | Sunni Islam |

Marwan Hasib Ibrahim Barghouti (Arabic: مروان حسيب ابراهيم البرغوثي; born 6 June 1959) is a Palestinian political figure convicted and imprisoned for murder by an Israeli court.[1] He is regarded as a leader of the First and Second Intifadas. Barghouti at one time supported the peace process, but later became disillusioned, and after 2000 went on to become a leader of the Al-Aqsa Intifada in the West Bank.[1][2] Barghouti is said to have founded Tanzim.[3] He has been called by some "the Palestinian Mandela".[4][5]

Israeli authorities have called Barghouti a terrorist, accusing him of directing numerous attacks, including suicide bombings, against civilian and military targets alike.[6] Barghouti was arrested by Israel Defense Forces in 2002 in Ramallah.[1] He was tried and convicted on charges of murder, and sentenced to five life sentences. Marwan Barghouti refused to present a defense to the charges brought against him, maintaining throughout that the trial was illegal and illegitimate.

Barghouti still exerts great influence in Fatah from within prison.[7] With popularity reaching further than that, there has been some speculation whether he could be a unifying candidate in a bid to succeed Mahmud Abbas.[8]

In the negotiations over the exchange of Palestinian prisoners for the captured Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit, Hamas insisted on including Barghouti in the deal with Israel.[9][10] However, Israel was unwilling to concede to that demand and despite initial reports that he indeed was to be released in the 11 October deal between Israel and Hamas, it was soon denied by Israeli sources.[11][12]

In November 2014, Barghouti urged the Palestinian Authority to immediately end security cooperation with Israel and called for a Third Intifada against Israel.[13]

Biography

Barghouti was born in the village of Kobar near Ramallah, and comes from the Barghouti clan, an extended family from Deir Ghassaneh. Mustafa Barghouti, a fellow Palestinian political figure, is a distant cousin. Barghouti was one of seven children, and his father was a migrant worker in Lebanon. His younger brother Muqbel described him as "a naughty and rebellious boy".[14]

Barghouti joined Fatah at age 15,[1] and he was a co-founder of the Fatah Youth Movement (Shabiba) on the West Bank. By the age of 18 in 1976, Barghouti was arrested by Israel for his involvement with Palestinian militant groups. He completed his secondary education and received a high school diploma while in jail. He is fluent in Hebrew.

Barghouti enrolled at Birzeit University (BZU) in 1983, though arrest and exile meant that he did not receive his B.A. (History and Political Science) until 1994. He earned an M.A. in International Relations, also from Birzeit, in 1998. As an undergraduate, he was active in student politics on behalf of Fatah and headed the BZU Student Council. On 21 October 1984, he married a fellow student, Fadwa Ibrahim. Fadwa took bachelor's and master's degrees in law and was a prominent advocate in her own right on behalf of Palestinian prisoners, before becoming the leading campaigner for her husband’s release from his current jail term. The couple has a daughter, Ruba (born 1986), and three sons, Qassam (born 1985), Sharaf (born 1989) and Arab (born 1990).

First Intifada

Barghouti became one of the major leaders in the West Bank of the First Intifada in 1987, leading Palestinians in a mass uprising against Israeli occupation.[1] During the uprising, he was arrested by Israel and deported to Jordan, where he stayed for seven years until he was permitted to return under the terms of the Oslo Accords in 1994.[1] Although he was a strong supporter of the peace process he doubted that Israel was committed to land-for-peace deals.[1] In 1996, he was elected to the Palestinian Legislative Council,[1] following which he began his active advocacy of the establishment of an independent Palestinian state. Barghouti campaigned against corruption in Arafat's administration and human rights violations by its security services, and he established relationships with a number of Israeli politicians and members of Israel's peace movement.[1] The formal position occupied by Barghouti was Secretary-General of Fatah in the West Bank.[15] By the summer of 2000, particularly after the Camp David summit failed, Barghouti was disillusioned and said that popular protests and "new forms of military struggle" would be features of the "next Intifada".[1]

Second Intifada

As the Second Intifada raged, Barghouti became increasingly popular as a leader of the Fatah armed branch, the Tanzim, seen as one of the major forces fighting against the Israel Defense Forces. Barghouti led marches to Israeli checkpoints, where riots broke out against Israeli soldiers and spurred on Palestinians in speeches at funerals and demonstrations, condoning the use of force to expel Israel from the West Bank and Gaza Strip.[1] He has stated that, "I, and the Fatah movement to which I belong, strongly oppose attacks and the targeting of civilians inside Israel, our future neighbor, I reserve the right to protect myself, to resist the Israeli occupation of my country and to fight for my freedom" and has said, "I still seek peaceful coexistence between the equal and independent countries of Israel and Palestine based on full withdrawal from Palestinian territories occupied in 1967."[16] During the second intifada Barghouti was accused by Israel of being a senior member of the Al-Aqsa Martyrs' Brigades, an organization which conducted numerous attacks and suicide bombings on civilians both within and outside of Israel proper, and has been accused of having directed some of these bombings personally.[6]

During his trial, Barghouti was found guilty of involvement in three attacks that killed a total of five people: a June 2001 attack in Ma'ale Adumim that killed a Greek monk, a January 2002 attack on a Givat Ze'ev gas station, the March 2002 Seafood market attack in Tel Aviv, and a car bombing in Jerusalem.[17]

Israeli imprisonment

Israel accused him of founding the al-Aqsa Martyrs' Brigades and attempted to assassinate him in 2001.[1] The missile hit his bodyguard's car, killing the bodyguard.[1] Barghouti survived but was arrested by the Israeli Army in Ramallah, on 15 April 2002 and transferred to the 'Russian Compound' police station in Jerusalem.

Amos Harel wrote in Haaretz that Barghouti was arrested by soldiers of the Duchifat Battalion who had approached the building hidden in an ambulance to avoid detection: "The Duchifat soldiers were squeezed into a protected ambulance in order to arrive as quickly as possible at the house where Barghouti was hiding, and to seal it off."[18]

Several months later, he was indicted in civilian court on charges of murder and attempted murder stemming from attacks carried out by the al-Aqsa Martyrs' Brigades on Israeli civilians and soldiers.[19][20]

Marwan Barghouti refused to present a defense to the charges brought against him, maintaining throughout that the trial was illegal and illegitimate.[21] However, he continued to stress that he supported armed resistance to the Israeli occupation, but condemned attacks on civilians inside Israel. Nonetheless, the evidence Israel presented at his trial stated that he supported and directed such attacks.[22] On 20 May 2004, he was convicted of 5 counts of murder – including authorizing and organizing the Seafood market attack in Tel Aviv in which 3 civilians inside Israel were killed. He was acquitted of 21 counts of murder in 33 other attacks for "lack of sufficient evidence." On 6 June 2004, he was sentenced to five life sentences for the five murders and 40 years imprisonment for the attempted murder.

Campaign for release

Since Barghouti's arrest, many of his supporters have campaigned for his release. They include prominent Palestinian figures, members of European Parliament and the Israeli group Gush Shalom. Reuters reported that some see Barghouti "as a Palestinian Nelson Mandela, the man who could galvanize a drifting and divided national movement if only he were set free by Israel".[23] According to The Jerusalem Post, "[u]nlike many in the Western media, Palestinian journalists and writers have rarely - if ever - referred to Barghouti as...the 'Palestinian Nelson Mandela.'"[24]

Some argue that Barghouti's arrest was illegal, pointing to his diplomatic immunity as a member of the Palestinian Parliament, as well as to the fact that he was arrested in an area over which Israel has no jurisdiction. They also point out that the transfer of a prisoner from occupied territory to the territory of the occupier violates the Fourth Geneva Convention.

Another approach is to suggest that Israel's freeing of Barghouti would be an excellent show of good faith in the peace process. This view gained popularity among the Israeli left after the 2005 Disengagement from the Gaza Strip. Still others, operating from a realpolitik perspective, have pointed out that allowing Barghouti to re-enter Palestinian politics could serve to bolster Fatah against gains in Hamas' popularity.[25] According to Pinhas Inbari of the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs,

"Hamas understands it needs to provide its supporters with some comfort, especially seeing the suffering of the Palestinian people. For this reason, Hamas is willing to accept Barghouti's release and to deal with him after he is free. Without the severe state of the Palestinian people, Hamas would object to the release of Barghouti.[26]

Following Barghouti's January 2006 re-election to the Palestinian Legislative Council, a debate over Barghouti's fate began anew in Israel, ranging from former MK Yossi Beilin's support for a Presidential pardon to the total refusal of any idea of early release. Israeli Foreign Minister Silvan Shalom stated,

"We must not forget that he is a cold-blooded murderer who was sentenced by the court to five life sentences… It is out of the question to free an assassin who has blood on his hands and was duly sentenced by a court.[27][28]

However several MKs, including Kadima MK Meir Sheetrit, suggested that Barghouti will likely be released as part of future peace negotiations, although they did not specify when. In January 2007, Israeli Deputy Prime Minister Shimon Peres declared that he would sign a presidential pardon for Marwan Barghouti if elected to the Israeli presidency.[29] However, despite Peres winning the presidency, a pardon was not issued.

Split from Fatah

On 14 December 2005, Barghouti announced that he had formed a new political party, al-Mustaqbal ("The Future"), mainly composed of members of Fatah's "Young Guard", who repeatedly expressed frustration with the entrenched corruption in the party. The list, which was presented to the Palestinian Authority's central elections committee on that day, included Mohammed Dahlan, Kadoura Fares, Samir Mashharawi and Jibril Rajoub.[21]

The split followed Barghouti's earlier refusal of Mahmoud Abbas' offer to be second on the Fatah party's parliamentary list, behind Palestinian Prime Minister Ahmed Qurei. Barghouti had actually topped the list,[30] but this had not become apparent until after the new party had been registered.

Reactions to the news was split. Some suggested that the move was a positive step towards peace, as Barghouti's new party could help reform major problems in Palestinian government. Others raised concern that it could wind up splitting the Fatah vote, inadvertently helping Hamas. Barghouti's supporters argued that al-Mustaqbal would split the votes of both parties, both from disenchanted Fatah members as well as moderate Hamas voters who do not agree with Hamas' political goals, but rather its social work and hard position on corruption. Some observers also hypothesized that the formation of al-Mustaqbal was mostly a negotiating tactic to get members of the Young Guard into higher positions of power within Fatah and its electoral list.

Barghouti eventually was convinced that the idea of leading a new party, especially one that was created by splitting from Fatah, would be unrealistic while he was still in prison. Instead he stood as a Fatah candidate in the January 2006 PLC elections, comfortably regaining his seat in the Palestinian Parliament.

Political activity in prison

In late 2004, Barghouti announced from his Israeli prison his intention to run in the Palestinian Authority presidential election in January 2005, called for following the death of President Yasser Arafat in November. On 26 November 2004, it appeared he would withdraw from the contest following pressure from the Fatah faction to support the candidacy of Mahmoud Abbas. However, just before the deadline on 1 December, Barghouti's wife registered him as an independent candidate. On 12 December, facing pressure from Fatah[31] to withdraw in favor of Abbas, he chose to abandon his candidacy for the benefit of Palestinian unity. On 11 May 2006, Palestinian leaders held in Israeli prisons released the National Conciliation Document of the Prisoners. The document was a proposal initiated by Marwan Barghouti and leaders of Hamas, the PFLP, the Palestinian Islamic Jihad and the DFLP that proposed a basis upon which a coalition government should be formed in the Palestinian Legislative Council. This came as a result of the political stalemate in the Palestinian territories that followed Hamas' election to the PLC in January 2006. Crucially, the document also called for negotiation with the state of Israel in order to achieve lasting peace. The document quickly gained popular currency and is now considered the bedrock upon which a national unity government should be achieved. According to Haaretz, Barghouti, although not officially represented in the negotiations of a Palestinian unity government in February 2007, played a major role in mediating between Hamas and Fatah and formulating the compromise reached on 8 February 2007.[32] In 2009, he was elected to party leadership at the Fatah Conference in Bethlehem.[10]

Popularity

Despite being out of the public eye for a few years, Marwan Barghouti remains a popular leader among the Palestinian people. According to polling data in mid-2012, 60% of Palestinians would vote for him for president of the Palestinian Authority if they were given that chance, and he would beat both Mahmoud Abbas and Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh for the top post.[33]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 "Profile: Marwan Barghouti". BBC News. 26 November 2009. Accessed 9 August 2011.

- ↑ Bahaa, Sherine. "'Israel's enemy number one'". Al-Ahram Weekly 18–24 April 2002. Issue no. 582. Accessed 9 August 2011.

- ↑ Palestine's Mandela by Uri Avnery. Accessed: 5 December 2009.

- ↑ Ross, Oakland (30 June 2007). "The destiny of Marwan Barghouti". The Toronto Star.

- ↑ Ross, Oakland (11 March 2009). "'Palestinian Mandela' pulls strings from jail". The Toronto Star.

- 1 2 Marwan Barghouti incitement. Accessed: 29 August 2010.

- ↑ "An interview with Marwan Barghouti". IMEU. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ↑ Mort, Jo-Ann (14 August 2009). "Why a Jailed Dissident Is Palestine's Best Hope". Foreign Policy.

- ↑ "Report: Israel refuses to release Ahmad Saadat". Ynetnews. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- 1 2 Reuters. "Labor minister: Israel must consider freeing Fatah victor Barghouti". Haaretz. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ↑ "Sbarro Female Terrorist Among Those Freed". Israel National News. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ↑ Keinon, Herb. "Breaking News". Jarusalem Post. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ↑ Umberto Bacchi, Marwan Barghouti Calls Third Intifada Against Israel. 11 November 2014, International Business Times.

- ↑ Bennet, James (19 November 2004). "Jailed in Israel, Palestinian Symbol Eyes Top Post". The New York Times.

- ↑ Tobias Kelly (December 2006). Cambridge Studies in Law and Society: Law, Violence and Sovereignty Among West Bank Palestinians. Cambridge University Press. p. 159. ISBN 9780521868068.

- ↑ Marwan Barghouti (16 January 2002). "Want Security? End the Occupation". The Washington Post.

- ↑ "Marwan Barghouti Convicted of Murder". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ↑ "גורמי ביטחון: ברגותי מפגין יהירות בחקירה". Haaretz. 18 April 2002. Retrieved 17 September 2011.

- ↑ Full indictment, Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs

- ↑ Indictment appendix listing all charges

- 1 2 "Barghouti, Marwan". MEDEA. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ↑ Issacharoff, Avi (26 January 2012). "In rare court appearance, Marwan Barghouti calls for a peace deal based on 1967 lines". Haaretz.

- ↑ "Marwan Barghouti: Peace talks with Israel have failed". Haaretz. Reuters. 19 November 2009.

- ↑ Khaled Abu Toameh (26 November 2009). "Analysis: Marwan Barghouti - A Nelson Mandela or a PR gimmick?". The Jerusalem Post.

- ↑ "The Blame Game – Forward.com"

- ↑ On the chances of the release of Gilad Shalit (Hebrew), Pinhas Inbari, 20 December 2007

- ↑ "Barghouti´s Popularity Spurs Campaign to Free Him". Israel National News. 25 January 2006. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ↑ "Israelis may release jailed Fatah leader". The Daily Star. 28 November 2005. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ↑ Bloomfield, David (6 November 2009). "Marwan Barghouti could stand as Palestinian president". The Telegraph. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- ↑ "Fatah splits before key election". BBC News. 15 December 2005. Accessed 9 August 2011.

- ↑ Barghouti withdrawal leaves Abbas with clear path to succeed Arafat

- ↑ article

- ↑ Haaretz, 27 June 2012, "Poll: Barghouti Would Defeat Abbas and Haniyeh in Vote for Palestinian President," http://www.haaretz.com/news/middle-east/poll-barghouti-would-defeat-abbas-and-haniyeh-in-vote-for-palestinian-president.premium-1.444382

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Marwan Barghouti. |

- Interview with Marwan Barghouti. "Competing Political Cultures". In: Beinin, Joel; Stein, Rebecca L. (eds) (2006). The Struggle for Sovereignty: Palestine and Israel, 1993-2005. Stanford University Press. pp. 105–111.

- Pratt, David (2006). Intifada: The Long Day of Rage. Casemate. First published by Sunday Herald Books.

- Haddad, Toufic. "Changing the Rules of the Game: A Conversation with Marwan Barghouti, Secretary-General of Fateh in the West Bank". In: Honig-Parnass, Tikva; Haddad, Toufic. (eds) (2007). Between the Lines: Readings on Israel, the Palestinians, and the U.S. "War on Terror". Haymarket Books. pp. 65–69.

- Blomfield, Adrian. "Marwan Barghouti could stand as Palestinian president". The Daily Telegraph. 6 November 2009. Accessed 9 August 2011.

External links

- What Marwan Barghouti Really Means to Palestinians Palestine Chronicle, 4 April 2012

- CS Monitor: The 'Palestinian Napoleon' Behind Mideast Cease-fire

- Bitter Circus Erupts as Israel Indicts a Top Fatah Figure The New York Times, 15 August 2002

- Uri Avnery, "Palestine's Mandela", New Internationalist, November 2007

- Israel's Ministry of Foreign Affairs page about Barghouti