Emergency evacuation

Emergency evacuation is the immediate and urgent movement of people away from the threat or actual occurrence of a hazard. Examples range from the small scale evacuation of a building due to a storm or fire to the large scale evacuation of a district because of a flood, bombardment or approaching weather system. In situations involving hazardous materials or possible contamination, evacuees may be decontaminated prior to being transported out of the contaminated area.

Reasons for evacuation

Evacuations may be carried out before, during or after disasters such as:

- Natural disasters

- eruptions of volcanoes,

- tropical cyclones

- floods,

- earthquakes

- tsunamis or

- wildfires/bushfires

Other reasons include:

- industrial accidents,

- traffic accidents, including train or aviation accidents,

- fire,

- military attacks,

- bombings,

- terrorist attacks

- military battles

- structural failure

- viral outbreak

Planning

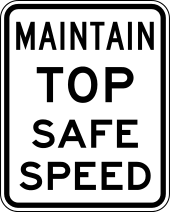

Emergency evacuation plans are developed to ensure the safest and most efficient evacuation time of all expected residents of a structure, city, or region. A benchmark "evacuation time" for different hazards and conditions is established. These benchmarks can be established through using best practices, regulations, or using simulations, such as modeling the flow of people in a building, to determine the benchmark. Proper planning will use multiple exits, contra-flow lanes, and special technologies to ensure full, fast and complete evacuation. Consideration for personal situations which may affect an individual's ability to evacuate is taken into account, including alarm signals that use both aural and visual alerts, and also evacuation equipment such as sleds, pads, and chairs for non-ambulatory people. Regulations such as building codes can be used to reduce the possibility of panic by allowing individuals to process the need to self-evacuate without causing alarm . Proper planning will implement an all-hazards approach so that plans can be reused for multiple hazards that could exist.

Evacuation sequence

The sequence of an evacuation can be divided into the following phases:

- detection

- decision

- alarm

- reaction

- movement to an area of refuge or an assembly station

- transportation

The time for the first four phases is usually called pre-movement time.

The particular phases are different for different objects, e.g., for ships a distinction between assembly and embarkation (to boats or rafts) is made. These are separate from each other. The decision whether to enter the boats or rafts is thus usually made after assembly is completed.

Small scale evacuations

The strategy of individuals in evacuating buildings was investigated by John Abrahams in 1994.[1] The independent variables were the complexity of the building and the movement ability of the individuals. With increasing complexity and decreasing motion ability, the strategy changes from "fast egress", through "slow egress" and "move to safe place inside building" (such as a staircase), to "stay in place and wait for help". The last strategy is the notion of using a designated Safe Haven on the floor. This is a section of the building that is reinforced to protect against specific hazards, such as fire, smoke or structural collapse. Some hazards may have Safe Havens on each floor, while a hazard such as a tornado, may have a single Safe Haven or safe room. Typically persons with limited mobility are requested to report to a Safe Haven for rescue by first responders. In most buildings, the Safe Haven will be in the stairwell.

The most common equipment in buildings to facilitate emergency evacuations are fire alarms, exit signs, and emergency lights. Some structures need special emergency exits or fire escapes to ensure the availability of alternative escape paths. Commercial passenger vehicles such as buses, boats, and aircraft also often have evacuation lighting and signage, and in some cases windows or extra doors that function as emergency exits. Commercial emergency aircraft evacuation is also facilitated by evacuation slides and pre-flight safety briefings. Military aircraft are often equipped with ejection seats or parachutes. Water vessels and commercial aircraft that fly over water are equipped with personal flotation devices and life rafts.

Large scale evacuations

The evacuation of districts is part of disaster management. Many of the largest evacuations have been in the face of war-time military attacks. Modern large scale evacuations are usually the result of natural disasters. The largest peace-time evacuations in the United States to date occurred during Hurricane Gustav and the category-5 Hurricane Rita (2005) in a scare one month after the flood-deaths of Hurricane Katrina.

Hurricane evacuations

Despite mandatory evacuation orders, many people did not leave New Orleans, United States, as Hurricane Katrina approached. Even after the city was flooded and uninhabitable, some people still refused to leave their homes.[2][3]

The longer a person has lived in a coastal area, the less likely they are to evacuate. A hurricane's path is difficult to predict. Forecasters know about hurricanes days in advance, but their forecasts of where the storm will hit are only educated guesses. Hurricanes give a lot of warning time compared to most disasters humans experience. However, this allows forecasters and officials to "cry wolf," making people take evacuation orders less seriously. Hurricanes can be predicted to hit a coastal town many times without the town ever actually experiencing the brunt of a storm. If evacuation orders are given too early, the hurricane can change course and leave the evacuated area unscathed. People may think they have weathered hurricanes before, when in reality the hurricane didn't hit them directly, giving them false confidence. Those who have lived on the coast for ten or more years are the most resistant to evacuating.[4]

Public transportation

Since Hurricane Katrina, there has been an increase in evacuation planning. Current best practices include the need to use multi-modal transportation networks. Hurricane Gustav used military airlift resources to facilitate evacuating people out of the affected area. More complex evacuation planning is now being considered, such as using elementary schools as rally points for evacuation. In the United States, elementary schools are usually more numerous in a community than other public structures. Their locations and inherent design to accommodate bus transportation makes it an ideal evacuation point.

Registries

Most local communities maintain registries for special needs individuals. These opt-in registries help with planning, as those that need government evacuation assistance are identified before the disaster. Registries used after a disaster are being used to help reunite families that have become separated after a disaster.

Enforcing evacuation orders

In the United States a person cannot be forced to evacuate under most conditions. To facilitate voluntary compliance with mandatory evacuation orders first responders and disaster management officials have used creative techniques such as asking people for the names and contact of their next of kin, writing their Social Security Numbers on their limbs and torso so that their remains can be identified,[5] and refusing to provide government services in the affected area, including emergency services.

Personal Evacuation Kits

In case of an emergency evacuation situation, it is important to have an individual emergency evacuation kit prepared and on hand prior to the emergency. An emergency evacuation kit is a container of food, clothing, water, and other supplies that can be used to sustain an individual during lag time. Lag time is the period between the actual occurrence of an emergency and when organized help becomes available, generally 72 hours, though this can vary from a few hours to several days. It may take this long for authorities to get evacuation shelters fully up and functional. During this time, evacuees may suffer fairly primitive conditions; no clean water, heat, lights, toilet facilities, or shelter. An emergency evacuation kit, or 72-hour kit, can help evacuees to endure the evacuation experience with dignity and a degree of comfort.

See also

- Civil defense

- Emergency Management

- Evacuation process simulation

- List of mass evacuations

- Emergency airplane evacuations

- Shelter in place

- Symmetry breaking of escaping ants

References

- ↑ Abrahams, John: "Fire escape in difficult circumstances", chapter 6, In: Stollard, 1994, "Design against fire".

- ↑ "New Orleans rescues continue, but some won't go" NPR 9-6-05

- ↑ "Rescuers urge residents to leave New Orleans" NPR 9-6-05

- ↑ http://www.scseagrant.org/pdf_files/ch_summer_02.pdf

- ↑ "Magic Marker strategy" New York Times 9-6-05

- Gershenfeld, Neil, Mathematical Modelling. OUP, Oxford, 1999.

- Hubert Klüpfel, A Cellular Automaton Model for Crowd Movement and Egress Simulation. Dissertation, Universität Duisburg-Essen, 2003.

- Stollard, P. and L. Johnson, Eds., "Design against fire: an introduction to fire safety engineering design", London, New York, 1994.

- Künzer, L. Myths Of Evacuation in FeuerTRUTZ International 1.2016, p. 8-11