Maurice Joly

| Maurice Joly | |

|---|---|

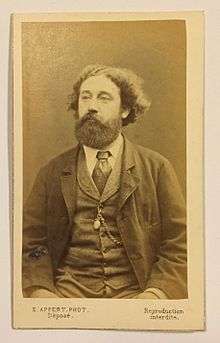

Albumen photograph by Eugène Appert, c. 1870 | |

| Born |

September 22, 1829 Lons-le-Saunier, France |

| Died |

July 15, 1878 (aged 48) Paris |

| Occupation | Writer, lawyer |

| Language | French |

| Nationality | French |

| Period | 1862-1878 |

| Genre | Political satire |

| Notable works | Dialogue aux enfers entre Machiavel et Montesquieu |

| French literature |

|---|

| by category |

| French literary history |

| French writers |

|

| Portals |

|

Maurice Joly (1829–1878) was a French publicist and lawyer known for his political satire titled Dialogue aux enfers entre Machiavel et Montesquieu ou la politique de Machiavel au XIXe siècle,[1] that attacked the regime of Napoleon III. Available English translations include: Dialogues in Hell between Machiavelli and Montesquieu by Herman Bernstein,[2] and The Dialogue in Hell Between Machiavelli and Montesquieu by John S. Waggoner.[3]

Known life

Most of the known information about Monsieur Joly is based upon his autobiographical sketch Maurice Joly, son passé, son programme, par lui-même,[4] written at Conciergerie prison in November 1870, where he was jailed for assault at Hôtel de Ville in Paris. Some additional facts are mentioned at Henry Rollin's book L'Apocalypse de notre temps,[5] and in Maurice Joly, un suicidé de la dèmocratie - a preface to modern publication of Joly's Dialogue aux enfers entre Machiavel et Montesquieu, Épilogue and César - by mysterious F. Leclercq.[6]

Joly was born in the small town of Lons-le-Saunier, in the department of Jura, to a French father and an Italian mother. He studied law in Dijon, but stopped in 1849 in order to go to Paris, where he worked as a clerk at various governmental institutions for about 10 years. He successfully completed his legal studies and was finally admitted to the Paris bar in 1859. Politically, Joly was a conservative, a monarchist, and a legitimist; he had no known use for republics/democracies or popular sovereignty.

He started writing in 1862, supplying literary portraits of his fellow lawyers to a small magazine "Gorgias", and later published these sketches as a stand-alone book Le Barreau de Paris,[7] followed by Les Principes de 89[8] and Supplément à la géographie politique du Jura.[9] Then Joly concocted a lampoon César, where he attacked the political regime of Napoleon III, a.k.a. Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte. The books were printed by Martin-Beaupré brothers and swiftly destroyed by the publishers. Not a single copy survived.

In 1864, Joly wrote his best-known book, The Dialogue in Hell Between Machiavelli and Montesquieu. The piece uses the literary device of a dialogue of the dead, invented by ancient Roman writer Lucian and introduced into the French belles-lettres by Bernard de Fontenelle in the 18th century. Shadows of the historical characters of Niccolo Machiavelli and Charles-Louis de Secondat, Baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu meet in Hell in the year 1864 and dispute on politics. In this way, Joly tried to conceal a direct, and then illegal, criticism of Louis-Napoleon's rule.

Joly relates, in his 1870 autobiography,[4] that one evening thinking of Abbé Galiani's treatise Dialogues sur le commerce des bleds[10] and walking by Pont Royal, he was inspired to write a dialogue between Montesquieu and Machiavelli. The noble baron Montesquieu (whom Joly consigned to Hell in his book because of Montesquieu's support of republics/democracies) would make the case for liberalism; the Florentine politician Machiavelli (whom Joly, not realising that Il Principe (The Prince) was itself a satire, consigned to Hell in his book for supposedly supporting usurpers, which was at odds with Joly's belief in "The Divine Right Of Kings") would present the case for despotism.

Machiavelli claims that he "... wouldn't even need twenty years to transform utterly the most indomitable European character and render it as a docile under tyranny as the debased people of Asia." Montesquieu insists that the liberal spirit of the peoples is invincible. In 25 dialogues, step by step, Machiavelli, who by Joly's plot covertly represents Napoleon III, explains how he would replace freedom with despotism in any given European country: "...Absolute power will no longer be an accident of fortune but will become a need" of the modern society. At the end, Machiavelli prevails. In the curtain-line Montesquieu exclaims "Eternal God, what have you permitted!..."[3]

The book was published anonymously (with the by-line par un contemporain, by a contemporary) in Brussels in 1864 and smuggled into France for distribution, but the print run was seized by the police immediately upon crossing the border. The police swiftly tracked down its author, and Joly was arrested. The book was banned. On 25 April 1865, he was sentenced to 18 months at the Sainte-Pélagie Prison in Paris. The second edition of "The Dialogues" was issued in 1868 under Joly's name.[11] This time, it reached the readers. But its author remained in obscurity. He established a new journal, Le Palais, that ended after a confrontation with the principal collaborator in the enterprise. After the fall of the Empire in 1870, Joly sought a governmental position from Jules Grévy. He failed in this too. Campaigning against Napoleon III at the French constitutional referendum, 1870, Joly wrote an epilogue to his "Dialogue". It was published in Le Gaulois [12] and La Cloche [13] magazines.

In 1871, he was a low-rank member of the Paris Commune[14][15]

and in his last years, he joined masonic lodge La Clémente amitié.

Though Joly gained laurels of a scandalous and bully barrator, he sued 10 newspapers, one after another, either for not accepting his stories or for not publishing news about him. Joly's name was completely forgotten, and in life, he did not attain the glory he so obsessively craved.

Joly was found dead on 15 July 1878 in his 5 Quai Voltaire apartment in Paris.[16] The declared cause of his death was gunshot suicide. The exact date of his death remains unknown.

Posthumous fame

The "Dialogue" and its author became famous later, inadvertently and for an enigmatic reason. In the beginning of 20th century Joly's book was used as a basis for The Protocols of the Elders of Zion,[17] an infamous Russian-made antisemitic literary forgery. There is an abundance of evidence that The Protocols were lavishly plagiarized from Joly's book,[18][19][20] however there are still skeptics who insist that it was Joly who plagiarized The Protocols and not vice versa.[21]

Italian writer Umberto Eco claims[22] that in the Dialogue Joly plagiarized seven pages or more from a popular novel Les Mystères du peuple by Eugene Sue.[23]

In 2015 one of the streets in Lons-le-Saunier was named Rue Maurice Joly.

Publications

- 1863: Le Barreau de Paris, études politiques et littéraires. Paris, Gosselin.

- 1863: Les Principes de 89 par Maurice Joly, avocat. Paris, E. Dentu.

- 1864: Dialogue aux enfers entre Machiavel et Montesquieu|Dialogue aux enfers entre Machiavel et Montesquieu ou la politique de Machiavel au XIXe siècle. Bruxelles, A. Mertens et fils.

- 1865: César, Paris, Martin-Beaupré frères.

- 1868: Recherches sur l'art de parvenir. Paris, Amyot.

- 1870: Maurice Joly, son passé, son programme, par lui-même. Paris, Lacroix, Verbɶckhoven et Co.

- 1870: Dialogue aux Enfers entre Machiavel et Montesquieu. Épilogue. Le Gaulois : littéraire et politique, 664, 30 April 1870, pp.2-3; La Cloche 2 May 1870 - 10 May 1870.

- 1872: Le Tiers-Parti républicain. Paris, E. Dentu.

- 1876: Les Affamés, étude de mœurs contemporains. Paris, E. Dentu.

References

- ↑ Maurice Joly (1864). Dialogue aux enfers entre Machiavel et Montesquieu ou la politique de Machiavel au XIXe siècle. Bruxelles: A. Mertens et fils.

- ↑ Herman Bernstein (1935). The Truth About "The Protocols of Zion". A Complete Exposure. New York: Covici Friede. ISBN 978-0870681769.

- 1 2 Maurice Joly (author); John S. Waggoner (translator) (2002). The Dialogue in Hell between Machiavelli and Montesquieu. Lexington Books. ISBN 0-7391-0337-7.

- 1 2 Maurice Joly (1870). Maurice Joly, son passé, son programme, par lui-même. Paris: Lacroix, Verbɶckhoven et Co.

- ↑ Henri Rollin (1939). L'Apocalypse de notre temps. Les dessous de la propagande allemande d'après des documents inédits. Problèmes et documents. Paris: Gallimard.

- ↑ F. Leclercq (1996). Le Plébiscite, épilogue du dialogue aux enfers entre Machiavel et Montesquieu, précédé de César. Paris-Zanzibar. ISBN 2-911314-02-6.

- ↑ Maurice Joly (1863). Le Barreau de Paris, études politiques et littéraires. Paris: Gosselin.

- ↑ Maurice Joly (1863). Les Principes de 89. Paris: E. Dentu.

- ↑ Maurice Joly (1864). Supplément à la géographie politique du Jura, dédié à la Société d'émulation de ce département. Paris: P.-A. Bourdier.

- ↑ Ferdinando Galiani (1770). Dialogues sur le commerce des bleds. London.

- ↑ Maurice Joly (1868). Dialogue aux Enfers entre Machiavel et Montesquieu, ou la Politique au XIXe siècle, par un contemporain [Maurice Joly]. Bruxelles: Tous les libraires.

- ↑ Maurice Joly (30 April 1870). "Dialogue aux Enfers entre Machiavel et Montesquieu. Épilogue.". Le Gaulois : littéraire et politique (in French). Paris (664): 2–3.

- ↑ Maurice Joly. "Dialogue aux Enfers entre Machiavel et Montesquieu. Epilogue.". La Cloche 2 May 1870 - 10 May 1870 (in French).

- ↑ Armand Dayot (1901). L'Invasion, Le Siege, La Commune. Paris: Ernest Flammarion. p. 321.

- ↑ Charles Feld; François Hincker (1971). Paris au front d'insurgé: la Commune en images. Paris: Livre-Club Diderot. p. 14.

- ↑ Hippolyte de Villemessant (17 July 1878). "Nouvelles Diverses". Figaro : journal non politique. Paris: Figaro: 3.

- ↑ Сергей Нилус (1905). Великое в малом и антихрист, как близкая политическая возможность. Записки православного. Царское Село.

- ↑ Philip Graves. "The truth about "The Protocols"". The Times, August 16, 17, and 18, 1921. London.

- ↑ Kevin Schlottmann (July 17, 2013). "Guide to the Bern Trial on the Protocols of the Elders of Zion Collection". http://findingaids.cjh.org. Leo Baeck Institute. Retrieved January 26, 2016. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ Cesare De Michelis (2004). The Non-Existent Manuscript: a Study of the Protocols of the Sages of Zion, Studies in Antisemitism Series. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-1727-7.

- ↑ Norman Cohn (April 1, 2006). Warrant for Genocide: The Myth of the Jewish World Conspiracy and the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. London: Serif. ISBN 978-1897959497.

- ↑ Umberto Eco (1994). Six Walks in the Fictional Woods. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-81050-3.

- ↑ Eugène Sue. Les Mystères du peuple ou Histoire d’une famille de prolétaires à travers les âges. Bruxelles, 1849-1857: Alphonse-Nicolas Lebègue.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |