Max Beerbohm

| Sir Max Beerbohm | |

|---|---|

|

From The Critic 1901 | |

| Born |

Henry Maximilian Beerbohm 24 August 1872 London, England |

| Died |

20 May 1956 (aged 83) Rapallo, Italy |

| Resting place | St. Paul's Cathedral, London |

| Occupation | Essayist, parodist, caricaturist |

Sir Henry Maximilian "Max" Beerbohm (24 August 1872 – 20 May 1956) was an English essayist, parodist, and caricaturist. He first became known in the 1890s as a dandy and a humorist. He was the drama critic for the Saturday Review from 1898 until 1910, when he relocated to Rapallo, Italy. In his later years he was popular for his occasional radio broadcasts. Among his best-known works is his only novel, Zuleika Dobson, published in 1911. His caricatures, drawn usually in pen or pencil with muted watercolour tinting, are in many public collections.

Early life

Born in 57 Palace Gardens Terrace, London[1] which is now marked with a blue plaque,[2] Henry Maximilian Beerbohm was the youngest of nine children of a Lithuanian-born grain merchant, Julius Ewald Edward Beerbohm (1811–1892). His mother was Eliza Draper Beerbohm (c.1833–1918), the sister of Julius's late first wife. His was a well-to-do London family.[3] He was also close to four half-siblings, one of whom, Herbert Beerbohm Tree, was already a renowned stage actor when Max Beerbohm was a child.[4] Other older half-siblings were the author and explorer Julius Beerbohm[5] and the author Constance Beerbohm. His nieces were Viola, Felicity and Iris Tree.

From 1881 to 1885 Max – he was always called simply "Max" and it is thus that he signed his drawings – attended the day school of a Mr Wilkinson in Orme Square. Mr Wilkinson, Beerbohm later said, "gave me my love of Latin and thereby enabled me to write English".[6] Mrs Wilkinson taught drawing to the students, the only lessons Beerbohm ever had in the subject.[5]

Beerbohm was educated at Charterhouse School and Merton College, Oxford from 1890, where he was Secretary of the Myrmidon Club. It was at school that he began writing. While at Oxford Beerbohm became acquainted with Oscar Wilde and his circle through his half-brother, Herbert Beerbohm Tree. In 1893 he met William Rothenstein, who introduced him to Aubrey Beardsley and other members of the literary and artistic circle connected with The Bodley Head.[7] Though he was an unenthusiastic student academically, Beerbohm became a well-known figure in Oxford social circles. He also began submitting articles and caricatures to London publications, which were met enthusiastically. In March 1893 he submitted an article on Oscar Wilde to the Anglo-American Times under the pen name "An American". Later in 1893 his essay "The Incomparable Beauty of Modern Dress" was published in the Oxford journal The Spirit Lamp by its editor, Lord Alfred Douglas.[8]

By 1894, having developed his personality as a dandy and humorist, and already a rising star in English letters, he left Oxford without a degree.[4] His A Defence of Cosmetics (The Pervasion of Rouge) appeared in the first edition of The Yellow Book in 1894, his friend Aubrey Beardsley being art editor at the time. At this time Oscar Wilde said of him "The gods have bestowed on Max the gift of perpetual old age."[9][10]

In 1895 Beerbohm went to the United States for several months as secretary to his half-brother Herbert Beerbohm Tree's theatrical company. He was fired when he spent far too many hours polishing the business correspondence. There he became engaged to Grace Conover, an American actress in the company, a relationship that lasted several years.

Writer and broadcaster

On his return to England Beerbohm published his first book, The Works of Max Beerbohm (1896), a collection of his essays which had first appeared in The Yellow Book. His first piece of fiction, The Happy Hypocrite, was published in volume XI of The Yellow Book in October 1896. Having been interviewed by George Bernard Shaw himself, in 1898 he followed Shaw as drama critic for the Saturday Review,[11] on whose staff he remained until 1910. At that time the Saturday Review was undergoing renewed popularity under its new owner, the writer Frank Harris, who would later become a close friend of Beerbohm's.

It was Shaw, in his final Saturday Review piece, who bestowed upon Beerbohm the lasting epithet, "the Incomparable Max"[4] when he wrote, "The younger generation is knocking at the door; and as I open it there steps spritely in the incomparable Max".[12]

In 1904 Beerbohm met the American actress Florence Kahn. In 1910 they married and moved to Rapallo in Italy, partly as an escape from the social demands and the expense of living in London. Here they remained for the rest of their lives except for the duration of World War I and World War II, when they returned to Britain, and occasional trips to England to take part in exhibitions of his drawings. In his years in Rapallo Beerbohm was visited by many of the eminent men and women of his day, including Ezra Pound, who lived nearby, Somerset Maugham, John Gielgud, Laurence Olivier and Truman Capote among others.[13] Beerbohm never learned to speak Italian in the five decades that he lived in Italy.[4]

From 1935 onwards, he was an occasional if popular radio broadcaster, talking on cars and carriages and music halls for the BBC. His radio talks were published in 1946 as Mainly on the Air. His wit is shown often enough in his caricatures but his letters contain a carefully blended humour—a gentle admonishing of the excesses of the day—whilst remaining firmly tongue in cheek. His lifelong friend Reginald Turner, who was also an aesthete and a somewhat witty companion, saved many of Beerbohm's letters.

Beerbohm's best-known works include A Christmas Garland (1912), a parody of literary styles, Seven Men (1919), which includes "Enoch Soames", the tale of a poet who makes a deal with the Devil to find out how posterity will remember him, and Zuleika Dobson (1911), a satire of undergraduate life at Oxford. This was his only novel, but was nonetheless very successful.

Caricaturist

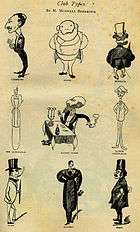

In the 1890s, while a student at Oxford University, Beerbohm showed great skill at observant figure sketching. His usual style of single-figure caricatures on formalised groupings, drawn in pen or pencil with delicately applied watercolour tinting, was established by 1896 and flourished until about 1930. In contrast to the heavier artistic style of the Punch tradition, he showed a lightness of touch and simplicity of line. Beerbohm's career as a professional caricaturist began when he was twenty: in 1892 the Strand Magazine published thirty-six of his drawings of 'Club Types'. Their publication dealt, Beerbohm said, "a great, an almost mortal blow to my modesty".[14] The first public exhibition of his caricatures was as part of a group show at the Fine Art Society in 1896; his first one-man show at the Carfax Gallery in 1901.

He was influenced by French cartoonists such as "Sem" (Georges Goursat) and "Caran d'Ache" (Emmanuel Poir).[15] Beerbohm was hailed by The Times in 1913 as "the greatest of English comic artists", by Bernard Berenson as "the English Goya", and by Edmund Wilson as "the greatest... portrayer of personalities – in the history of art".[16]

Usually inept with hands and feet, Beerbohm excelled in heads and with dandified male costume of a period whose elegance became a source of nostalgic inspiration. His collections of caricatures included Caricatures of Twenty-five Gentlemen (1896), The Poets' Corner (1904), Fifty Caricatures (1913) and Rossetti and His Circle (1922). His caricatures were published widely in the fashionable magazines of the time, and his works were exhibited regularly in London at the Carfax Gallery (1901–08) and Leicester Galleries (1911–57). At his Rapallo home he drew and wrote infrequently and decorated books in his library. These were sold at auction by Sotheby's of London on 12 and 13 December 1960 following the death of his second wife and literary executor Elisabeth Jungmann.[15]

His Rapallo caricatures were mostly of late Victorian and Edwardian political, literary and theatrical personalities. The court of Edward VII had a special place as a subject for affectionate ridicule. Many of Beerbohm's later caricatures were of himself.[5]

Major collections of Beerbohm's caricatures are in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford; the Tate collection; the Victoria and Albert Museum; Charterhouse School; the Clark Library, University of California; and the Lilly Library, Indiana University; depositories of both caricatures and archival material include Merton College, Oxford; the Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin; the Robert H. Taylor collection, Princeton University Library; the Houghton Library, Harvard University; and the privately owned Mark Samuels Lasner collection.[5]

Personal life

Beerbohm married the actress Florence Kahn in 1910. There has been speculation that he was a non-active homosexual (Malcolm Muggeridge, who much disliked him, imputed homosexuality to him), that his marriage was never consummated, that he was a "natural celibate" or even just asexual.[17][18] David Cecil wrote that, "though he showed no moral disapproval of homosexuality, [Beerbohm] was not disposed to it himself; on the contrary he looked upon it as a great misfortune to be avoided if possible." Cecil quotes a letter from Beerbohm to Oscar Wilde's friend Robert Ross in which he asks Ross to keep Reggie Turner from the clutches of Lord Alfred Douglas, "I really think Reg is at a rather crucial point of his career – and should hate to see him fall an entire victim to the love that dare not tell its name."[19] The fact is that not much is known of Beerbohm's private life.

Evelyn Waugh also speculated that Beerbohm had made a mariage blanc with Florence Kahn, but added: "Beerbohm remarked of Ruskin that it was surprising he should marry, without knowing he was impotent." Waugh also observed, "the question is of little importance in an artist of Beerbohm's quality."[20]

There was also some speculation during his lifetime that Beerbohm was Jewish. Muggeridge assumed that Beerbohm's Jewishness was certain. Beerbohm responded by saying that, disappointingly for him, he was not. However, both of his wives were Jews of German stock, although Florence was born and reared in Memphis, Tennessee, in an immigrant family. She is described as an American.[21] When asked by George Bernard Shaw if he had any Jewish ancestors, Beerbohm replied: "That my talent is rather like Jewish talent I admit readily... But, being in fact a Gentile, I am, in a small way, rather remarkable, and wish to remain so."[19] In his poem Hugh Selwyn Mauberley Ezra Pound, a neighbour in Rapallo, caricatured Beerbohm as "Brennbaum", a Jewish artist.[22]

He was knighted by George VI in 1939; it was thought that this token of esteem had been delayed by his mockery in 1911 of the king's parents, about whom he had written a satiric verse, "Ballade Tragique a Double Refrain".[23] In 1942 the Maximilian Society was created in Beerbohm's honour, on the occasion of his seventieth birthday. Formed by a London drama critic, it was made up of 70 distinguished members, and planned to add one more member on each of Beerbohm's successive birthdays. In their first meeting a banquet was held to pay homage to the great man, and he was presented with seventy bottles of wine.[4]

He died at the Villa Chiara, a private hospital in Rapallo, Italy, aged 83, shortly after marrying his former secretary and companion, Elisabeth Jungmann.[24] Beerbohm was cremated in Genoa and his ashes were interred in the crypt of St. Paul's Cathedral, London, on 29 June 1956.

Media portrayals

In the BBC 1982 Playhouse drama Aubrey, written by John Selwyn Gilbert, Beerbohm was portrayed by actor Alex Norton. The drama followed Aubrey Beardsley's life from the time of Oscar Wilde’s arrest in April 1895, which resulted in Beardsley losing his position at The Yellow Book, to his death from tuberculosis in 1898.[25]

Bibliography

Written works

- The Works of Max Beerbohm, with a Bibliography by John Lane (1896)

- The Happy Hypocrite (1897)

- More (1899)

- Yet Again (1909)

- Zuleika Dobson; or, An Oxford Love Story (1911)

- A Christmas Garland, Woven by Max Beerbohm (1912)

- Seven Men (1919; enlarged edition as Seven Men, and Two Others, 1950)

- Herbert Beerbohm Tree: Some Memories of Him and of His Art (1920, ed. by Max Beerbohm)

- And Even Now (1920)

- A Peep into the Past (1923)

- Around Theatres (1924)

- A Variety of Things (1928)

- The Dreadful Dragon of Hay Hill (1928)

- Lytton Strachey (1943) Rede Lecture

- Mainly on the Air (1946; enlarged edition 1957)

- The Incomparable Max: A Collection of Writings of Sir Max Beerbohm" (1962)

- Max in Verse: Rhymes and Parodies (1963, ed. by J. G. Riewald)

- Letters to Reggie Turner (1964, ed. by Rupert Hart-Davis)

- More Theatres, 1898–1903 (1969, ed. by Rupert Hart-Davis)

- Selected Prose (1970, ed. by Lord David Cecil)

- Max and Will: Max Beerbohm and William Rothenstein: Their Friendship and Letters (1975, ed. by Mary M. Lago and Karl Beckson)

- Letters of Max Beerbohm: 1892–1956 (1988, ed. by Rupert Hart-Davis)

- Last Theatres (1970, ed. by Rupert Hart-Davis)

- A Peep into the Past and Other Prose Pieces (1972)

- Max Beerbohm and "The Mirror of the Past" (1982, ed. Lawrence Danson)

Collections of caricatures

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Max Beerbohm. |

- Caricatures of Twenty-five Gentlemen (1896)

- The Poets' Corner (1904)

- A Book of Caricatures (1907)

- Cartoons: The Second Childhood of John Bull (1911)

- Fifty Caricatures (1913)

- A Survey (1921)

- Rossetti and His Circle (1922)

- Things New and Old (1923)

- Observations (1925)

- Heroes and Heroines of Bitter Sweet (1931) five drawings in a portfolio

- Max's Nineties: Drawings 1892–1899 (1958, ed. Rupert Hart-Davies and Allan Wade)

- Beerbohm's Literary Caricatures: From Homer to Huxley (1977, ed. J. G. Riewald)

- Max Beerbohm Caricatures (1997, ed. N. John Hall)

- Enoch Soames: A Critical Heritage (1997)

Gallery

'Dante Gabriel Rossetti in His Back-Garden' from The Poets' Corner (1904)

'Dante Gabriel Rossetti in His Back-Garden' from The Poets' Corner (1904).jpg) Two of Beerbohm's self-portraits. "The Theft" depicts him stealing a book from the library in 1894. "The Restitution" shows him returning that book in 1920.

Two of Beerbohm's self-portraits. "The Theft" depicts him stealing a book from the library in 1894. "The Restitution" shows him returning that book in 1920.

Further reading

- Behrman, S. N., Portrait of Max. (1960)

- Cecil, Lord David (1985) [1964], Max: A Biography of Max Beerbohm

- Danson, Lawrence. Max Beerbohm and the Act of Writing. (1989)

- Felstiner, John. The Lies of Art: Max Beerbohm's Parody and Caricature. (1972)

- Gallatin, A. H. Bibliography of the Works of Max Beerbohm. (1952)

- ———————— (1944), Max Beerbohm: Bibliographical Notes.

- Grushow, Ira. The Imaginary Reminiscences of Max Beerbohm. (1984)

- Hall, N. John (2002), Max Beerbohm: A Kind of a Life.

- Hart-Davis, Rupert A Catalogue of the Caricatures of Max Beerbohm. (1972)

- Lago, Mary, and Karl Beckson, eds. Max and Will : Max Beerbohm and William Rothenstein, their friendship and letters, 1893–1945. (1975).

- Lynch, Bohun. Max Beerbohm in Perspective. (1922)

- McElderderry, Bruce J. Max Beerbohm. (1971)

- Riewald, J. G. Sir Max Beerbohm, Man and Writer: A Critical Analysis with a Brief Life and Bibliography. (1953)

- ———————— (1974), The Surprise of Excellence: Modern Essays of Max Beerbohm.

- Riewald, JG (1991), Remembering Max Beerbohm: Correspondence Conversations Criticisms.

- Viscusi, Robert. Max Beerbohm, or the Dandy Dante: Rereading with Mirrors. (1986)

- Waugh, Evelyn. "Max Beerbohm: A Lesson in Manners." (Atlantic, September 1956)

See also

References

- ↑ The Times, 26 August 1872,

On the 24th instant, at 57 Palace Gardens Terrace, Kensington, the wife of JE Beerbohm, Esq., of a son

Missing or empty|title=(help). - ↑ "Max Beerbohm Blue Plaque". openplaques.org. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ↑ Baron, Wendy (2006), Sickert: Paintings and Drawings, Yale University Press, p. 315, ISBN 0-300-11129-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Staley, Thomas F, ed. (1984), Dictionary of Literary Biography, 34: British Novelists, 1890–1929: Traditionalists, Gale Research.

- 1 2 3 4 Hall, N John (January 2008) [2004], "Beerbohm, Sir Henry Maximilian [Max] (1872–1956)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.), Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Rothenstein, William (1932), Men and Memories: recollections of William Rothenstein, 1900–1922, pp. 370–71.

- ↑ Max Beerbohm: An Inventory of His Art Collection, U Texas: Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center.

- ↑ Mix, Katherine Lyon (1974), Max and the Americans, Vermont: The Stephen Greene Press, p. 3.

- 1 2 Tweed Conrad, Oscar Wilde in Quotation: 3,100 Insults, Anecdotes and Aphorisms, Topically Arranged with Attributions McFarland and Company, Inc., Publishers (2006) pg. 215 Google Books

- 1 2 Adam Gopnik, The Comparable Max: Max Beerbohm's cult of the diminutive - The New Yorker (2015)

- ↑ Levant, Oscar (1969) [1968], The Unimportance of Being Oscar, Pocket Books, p. 49, ISBN 0-671-77104-3.

- ↑ Alyson J. Shaw, Introduction: The Incomparable Max and the Unspeakable Oscar, Part 1 of The Divinity and the Disciple: Oscar Wilde in the Letters of Max Beerbohm, 1892–1895, Victorian Web, retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ↑ Max Beerbohm: Wit, Elegance and Caricature (PDF), 2005.

- ↑ Beerbohm, Max (October 1946), "When 9 was nineteen", Strand Magazine: 51.

- 1 2 Max Beerbohm, Answers.com.

- ↑ Hall, N John (1997), Max Beerbohm's Caricatures, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-07217-1.

- ↑ Hall 2002, pp. 120–21.

- ↑ Muggeridge, Malcolm (1966), "The legend of Max", Tread Softly For You Tread on My Jokes, Fontana. Muggeridge does not speculate, he asserts, but without providing clear evidence. He also asserts Beerbohm's Jewish ancestry, again without supplying confirmation. The article describes Muggeridge's visit to Beerbohm in Rapallo late in Beerbohm's life.

- 1 2 Epstein, Joseph (11 November 2002), "The Beerbohm Cult", The Weekly Standard.

- ↑ Waugh, Evelyn (1977), "The Max Behind the Mask", in Gallagher, Donat, Evelyn Waugh: a little order. A selection from his journalism, London: Eyre Methuen, pp. 114–17, ISBN 0-413-32700-0. Waugh does not give a source for this remark of Beerbohm's, though the two had met and corresponded occasionally.

- ↑ Cecil, Lord David, Max(Atheneum, New York 1985) p. 228-229

- ↑ "Hugh Selwyn Mauberley", Answers.

- ↑ Ballade Tragique a Double Refrain by Sir Max Beerbohm.

- ↑ Hall 2002, p. 246.

- ↑ Gilbert, John Sewyn (22 June 2008), Aubrey, John Coulthart.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Max Beerbohm |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Max Beerbohm |

- Artcyclopedia entry

- Works by Max Beerbohm at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Max Beerbohm at Internet Archive

- Works by Max Beerbohm at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Victorian Web: Max Beerbohm

- Enoch Soames bibliography

- Free downloads in HTML, PDF, text formats at ebooktakeaway.com

- Max Beerbohm Collection at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin

- Mary Lago Collection at the University of Missouri Libraries