Mensa (constellation)

| Constellation | |

|

| |

| Abbreviation | Men |

|---|---|

| Genitive | Mensae |

| Pronunciation |

/ˈmɛnsə/ genitive: /ˈmɛnsiː/ |

| Symbolism | the Table Mountain |

| Right ascension | 4 ~ 7.5 |

| Declination | −71 ~ −85.5 |

| Family | La Caille |

| Quadrant | SQ1 |

| Area | 153 sq. deg. (75th) |

| Main stars | 4 |

| Bayer/Flamsteed stars | 16 |

| Stars with planets | 2 |

| Stars brighter than 3.00m | none |

| Stars within 10.00 pc (32.62 ly) | none |

| Brightest star | α Men (5.09m) |

| Nearest star |

α Mensae (33.10 ly, 10.15 pc) |

| Messier objects | none |

| Meteor showers | none |

| Bordering constellations |

Chamaeleon Dorado Hydrus Octans Volans |

|

Visible at latitudes between +4° and −90°. Best visible at 21:00 (9 p.m.) during the month of January. | |

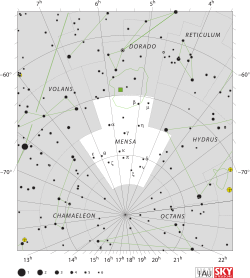

Mensa is a small constellation in the Southern Celestial Hemisphere between Scorpius and Centaurus, one of twelve drawn up in the 18th century by French astronomer Nicolas Louis de Lacaille. Its name is Latin for table, though it originally depicted Table Mountain and was known as Mons Mensae. One of the 88 modern constellations, it covers a keystone-shaped wedge of sky stretching from approximately 4h to 7.5h of right ascension, and −71 to −85.5 degrees of declination. Other than the south polar constellation of Octans, it is the most southerly of constellations. As a result, it is essentially unobservable from the Northern Hemisphere.

One of the faintest constellations in the night sky, Mensa boasts no bright stars. Its brightest star, Alpha Mensae is barely visible in suburban skies. Two star systems in Mensa have been found to have planets, and part of the Large Magellanic Cloud lies within the constellation's borders.

History

Initially known as Mons Mensae, Mensa was created by Nicolas Louis de Lacaille out of dim Southern Hemisphere stars in honor of Table Mountain, a South African mountain overlooking Cape Town. He recalled that the Magellanic clouds were sometimes known as Cape clouds, and that Table Mountain was often covered in cloud when a southeasterly stormy wind blew. Hence he made a "table" in the sky under the clouds.[1] Lacaille had observed and catalogued 10,000 southern stars during a two-year stay at the Cape of Good Hope. He devised 14 new constellations in uncharted regions of the Southern Celestial Hemisphere not visible from Europe. Mensa was the only constellation that did not honor an instrument that symbolised the Age of Enlightenment.[2] John Herschel proposed shrinking the name to one word in 1844, noting that Lacaille himself had abbreviated his constellations thus on occasion.[3]

Although the stars of Mensa do not feature in any ancient mythology, the mountain it is named after has a rich mythology. Called "Tafelberg" in Dutch and German, the mesa has two neighboring mountains called "Devil's Peak" and "Lion's Head". Table Mountain features in the mythology of the Cape of Good Hope, notorious for its storms—the explorer Bartolomeu Dias saw the mesa as a mythical anvil for storms. Another myth relating to its dangers comes from Sinbad the Sailor, an Arabic folk hero who saw the mountain as a magnet pulling his ships to the bottom of the sea.[4]

Characteristics

Mensa is bordered by Dorado to the north, Hydrus to the northwest and west, Octans to the south, Chamaeleon to the east and Volans to the northeast. Covering 153.5 square degrees and 0.372% of the night sky, it ranks 75th of the 88 constellations in size.[5] The three-letter abbreviation for the constellation, as adopted by the International Astronomical Union in 1922, is 'Men'.[6] The official constellation boundaries, as set by Eugène Delporte in 1930, are defined by a polygon of eight segments (illustrated in infobox). In the equatorial coordinate system, the right ascension coordinates of these borders lie between 03h 12m 55.9008s and 07h 36m 51.5289s, while the declination coordinates are between −69.75° and −85.26°.[7] The whole constellation is visible to observers south of latitude 5°N.[5][lower-alpha 1]

Notable features

Stars

Lacaille labelled eleven stars with Bayer designations Alpha through to Lambda (excluding Kappa). Gould later added Kappa, Mu, Nu, Xi and Pi Mensae. Stars as dim as these were not generally given designations; however, Gould felt their closeness to the South Celestial Pole warranted naming.[1] Overall, there are 22 stars within the constellation's borders brighter than or equal to apparent magnitude 6.5.[lower-alpha 2][5]

Mensa contains no bright stars, with Alpha Mensae its brightest star with a barely visible apparent magnitude of 5.09,[9] making it the faintest constellation in the entire sky. Alpha Mensae is a solar-type star (class G7V) 33.26 ± 0.05 light-years from Earth.[10] An infrared excess has been detected around this star, most likely indicating the presence of a circumstellar disk at a radius of over 147 AU. The temperature of this dust is below 22 K.[11] No planetary companions have yet been discovered around it. It has a red dwarf companion star at an angular separation of 3.05 arcseconds; equivalent to a projected separation of roughly 30 AU.[9][12] [13] Pi Mensae, on the other hand, while also solar-type (G1) and at 59 light-years, has been found to have a large gas giant in an eccentric orbit crossing the habitable zone, which would effectively rule out the existence of any habitable planets.

Beta Mensae is a yellow giant of spectral type G8III located 790 ± 40 light-years distant from earth.[10]

Gamma Mensae is an orange giant of spectral type K2III located 102 ± 3 light-years distant from earth.[10]

W Mensae is an unusual yellow supergiant that belongs to a rare class of star known as a R Coronae Borealis variable. It is located in the Large Magellanic Cloud.

Deep-sky objects

Mensa contains part of the Large Magellanic Cloud (the rest being in Dorado).[14]

The first images taken by the Chandra X-Ray Observatory were of PKS 0637-752, a quasar in Mensa with a large gas jet visible in both optical and x-ray wavelengths.[15]

Notes

- ↑ While parts of the constellation technically rise above the horizon to observers between 5°N and 20°N, stars within a few degrees of the horizon are to all intents and purposes unobservable.[5]

- ↑ Objects of magnitude 6.5 are among the faintest visible to the unaided eye in suburban-rural transition night skies.[8]

References

- References

- 1 2 Wagman 2003, pp. 207–08.

- ↑ Wagman 2003, pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Herschel, John (1844). "Farther Remarks on the Division of Southern Constellations". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 6 (5): 60–62.

- ↑ Staal 1988, p. 259.

- 1 2 3 4 Ridpath, Ian. "Constellations: Lacerta–Vulpecula". Star Tales. Self-published. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ↑ Russell, Henry Norris (1922). "The New International Symbols for the Constellations". Popular Astronomy. 30: 469. Bibcode:1922PA.....30..469R.

- ↑ "Mensa, Constellation Boundary". The Constellations. International Astronomical Union. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ↑ Bortle, John E. (February 2001). "The Bortle Dark-Sky Scale". Sky & Telescope. Sky Publishing Corporation. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- 1 2 "LTT 2490 -- High proper-motion star". SIMBAD. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- 1 2 3 van Leeuwen, F. (2007). "Validation of the New Hipparcos Reduction". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 474 (2): 653–64. arXiv:0708.1752

. Bibcode:2007A&A...474..653V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357.

. Bibcode:2007A&A...474..653V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357. - ↑ Eiroa, C.; Marshall, J. P.; Mora, A.; Montesinos, B.; Absil, O.; Augereau, J. Ch.; Bayo, A.; Bryden, G.; Danchi, W.; del Burgo, C.; Ertel, S.; Fridlund, M.; Heras, A. M.; Krivov, A. V.; Launhardt, R.; Liseau, R.; Löhne, T.; Maldonado, J.; Pilbratt, G. L.; Roberge, A.; Rodmann, J.; Sanz-Forcada, J.; Solano, E.; Stapelfeldt, K.; Thébault, P.; Wolf, S.; Ardila, D.; Arévalo, M.; Beichmann, C.; Faramaz, V.; González-García, B. M.; Gutiérrez, R.; Lebreton, J.; Martínez-Arnáiz, R.; Meeus, G.; Montes, D.; Olofsson, G.; Su, K. Y. L.; White, G. J.; Barrado, D.; Fukagawa, M.; Grün, E.; Kamp, I.; Lorente, R.; Morbidelli, A.; Müller, S.; Mutschke, H.; Nakagawa, T.; Ribas, I.; Walker, H. (July 2013). "DUst around NEarby Stars. The survey observational results". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 555: A11. arXiv:1305.0155

. Bibcode:2013A&A...555A..11E. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201321050.

. Bibcode:2013A&A...555A..11E. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201321050. - ↑ Eggenberger, A.; et al. (2007). "The impact of stellar duplicity on planet occurrence and properties. I. Observational results of a VLT/NACO search for stellar companions to 130 nearby stars with and without planets". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 474 (1): 273–291. Bibcode:2007A&A...474..273E. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20077447.

- ↑ "HD 43834B -- Star". SIMBAD. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 2010-03-26. (details on the stellar properties of the companion star)

- ↑ Tirion, Wil; Rappaport, Barry; Remaklus, Will (2012). Uranometria 2000.0 (All Sky ed.). Willmann-Bell. Chart 212. ISBN 978-0-943396-97-2.

- ↑ "Chandra Discovery of a 100 kiloparsec X-Ray Jet in PKS 0637-752" http://iopscience.iop.org/1538-4357/540/2/L69/fulltext/005370.text.html

- Citations

- Ridpath, Ian; Tirion, Wil (2007), Stars and Planets Guide, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-13556-4

- Staal, Julius D.W. (1988), The New Patterns in the Sky: Myths and Legends of the Stars, The McDonald and Woodward Publishing Company, ISBN 0-939923-04-1

- Wagman, Morton (2003). Lost Stars: Lost, Missing and Troublesome Stars from the Catalogues of Johannes Bayer, Nicholas Louis de Lacaille, John Flamsteed, and Sundry Others. Blacksburg, Virginia: The McDonald & Woodward Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-939923-78-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mensa. |

- The Deep Photographic Guide to the Constellations: Mensa

- Star Tales – Mensa

- Mensa Constellation at Constellation Guide

Coordinates: ![]() 05h 00m 00s, −80° 00′ 00″

05h 00m 00s, −80° 00′ 00″