Midnight Express (film)

| Midnight Express | |

|---|---|

Original theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Alan Parker |

| Produced by |

Alan Marshall David Puttnam |

| Screenplay by | Oliver Stone |

| Based on |

Midnight Express by Billy Hayes William Hoffer |

| Starring |

Brad Davis Randy Quaid John Hurt Paul L. Smith Irene Miracle |

| Music by | Giorgio Moroder |

| Cinematography | Michael Seresin |

| Edited by | Gerry Hambling |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 121 minutes |

| Country |

United States United Kingdom Turkey |

| Language |

English Turkish Maltese |

| Budget | $2.3 million |

| Box office | $35 million[1] |

Midnight Express is a 1978 American-British-Turkish prison drama film directed by Alan Parker, produced by David Puttnam and starring Brad Davis, Irene Miracle, Bo Hopkins, Paolo Bonacelli, Paul L. Smith, Randy Quaid, Norbert Weisser, Peter Jeffrey and John Hurt. It is based on Billy Hayes' 1977 non-fiction book Midnight Express and was adapted into the screenplay by Oliver Stone.

Hayes was a young American student sent to a Turkish prison for trying to smuggle hashish out of Turkey. The film deviates from the book's accounts of the story – especially in its portrayal of Turks – and some have criticized this version, including Billy Hayes himself. Later, both Stone and Hayes expressed their regret about how Turkish people were portrayed in the film.[2][3] The film's title is prison slang for an inmate's escape attempt.

Plot

On October 6, 1970, while on holiday in Istanbul, Turkey, American college student Billy Hayes straps 2 kg of hashish blocks to his chest. While attempting to board a plane back to the United States with his girlfriend, Billy is arrested by Turkish police on high alert due to fear of terrorist attacks. He is strip-searched, photographed and questioned. After a while, a shadowy American (who is never named, but is nicknamed "Tex" by Billy due to his thick Texan accent) arrives, takes Billy to a police station and translates for Billy for one of the detectives. On questioning Billy tells them that he bought the hashish from a taxicab driver, and offers to help the police track him down in exchange for his release. Billy goes with the police to a nearby market and points out the cab driver, but when they go to arrest the cabbie, it becomes apparent that the police have no intention of keeping their end of the deal with Billy. He sees an opportunity and makes a run for it, only to get cornered and recaptured by the mysterious American.

During his first night in holding at a local jail, a freezing-cold Billy sneaks out of his cell and steals a blanket. Later that night he is rousted from his cell and brutally beaten by chief guard Hamidou for the blanket theft.

He wakes a few days later in Sağmalcılar Prison, surrounded by fellow Western prisoners Jimmy (an American — in for stealing two candlesticks from a mosque), Max (an English heroin addict) and Erich (a Swede) who help him to his feet. Jimmy tells Billy that the prison is a dangerous place for foreigners like themselves, and that no one can be trusted – not even the young children.

Billy meets his father, a U.S representative and a Turkish lawyer to discuss what will happen to him. Billy is sent to trial for his case where the angry prosecutor makes a case against him for drug smuggling. The lead judge is sympathetic to Billy and gives him only a four-year sentence for drug possession. Billy and his father are horrified at the outcome but their Turkish lawyer insists that the term is a very good result.

Jimmy tries to encourage Billy to become part of an escape attempt through the prison's tunnels. Believing he is to be released soon Billy rebuffs Jimmy who goes on to attempt an escape himself being brutally beaten for this. In 1974, Billy's sentence is overturned by the Turkish High Court in Ankara after a prosecution appeal (the prosecutor originally wished to have him found guilty of smuggling and not the lesser charge of possession), and he is ordered to serve a 30-year-to-life term for his crime. Billy goes along with a prison-break Jimmy has masterminded. Billy, Jimmy, and Max try to escape through the catacombs below the prison, but their plans are revealed to the prison authorities by fellow-prisoner Rifki. His stay becomes harsh and brutal: terrifying scenes of physical and mental torture follow one another, culminating in Billy having a breakdown. He beats up and nearly kills Rifki. Following this breakdown, he is sent to the prison's ward for the insane where he wanders in a daze among the other disturbed and catatonic prisoners. He meets fellow prisoner Ahmet whilst participating in the regular inmate activity of walking in a circle around a pillar. Ahmet claims to be a philosopher from Oxford University and engages him in conversation to which Billy is unresponsive.

In 1975, Billy's girlfriend Susan comes to see him. Devastated at what has happened to Billy, she tells him that he has to escape or else he will die in there. She leaves him a scrapbook with money hidden inside as "a picture of your good friend Mr. Franklin from the bank," – hoping Billy can use it to help him escape. Her visit moves Billy strongly, and he regains his senses. He says goodbye to Max, telling him not to die and promising to come back for him. He bribes Hamidou into taking him to the sanitarium, where there are no guards. Instead, Hamidou takes Billy past the sanitarium to another room – and prepares to rape him. Fighting back, Billy inadvertently kills Hamidou by pushing him onto a coat hook. He seizes the opportunity to escape by putting on a guard's uniform and walking out of the front door. In the epilogue, it is explained that – on the night of October 4, 1975 – he successfully crossed the border to Greece, and arrived home three weeks later.

Cast

- Brad Davis as Billy Hayes

- Irene Miracle as Susan

- Bo Hopkins as "Tex"

- Paolo Bonacelli as Rifki

- Paul L. Smith as Hamidou

- Randy Quaid as Jimmy Booth

- Norbert Weisser as Erich

- John Hurt as Max

- Kevork Malikyan as the Prosecutor

- Yashaw Adem as the Airport police chief

- Mike Kellin as Mr. Hayes

- Franco Diogene as Yesil

- Michael Ensign as Stanley Daniels

- Gigi Ballista as the Judge

- Peter Jeffrey as Ahmet

- Michael Yannatos as Court translator

Production

Although the story is set largely in Turkey, the movie was filmed almost entirely at Fort Saint Elmo in Valletta, Malta, after permission to film in Istanbul was denied.[4][5] Ending credits of the movie state: "Made entirely on location in Malta and recorded at EMI Studios, Borehamwood by Columbia Pictures Corporation Limited 19/23 Wells Street, London, W1 England."

A made-for-TV documentary of the film, ''I'm Healthy, I'm Alive, and I'm Free'' (alternative title; "The Making of Midnight Express"), was released on January 1st, 1977. It is seven minutes long, and it ran on television. This documentary features commentary from the cast and crew on how they worked together during production, and the effort it took from beginning to completion. It also includes footage from the creation of the film, and director Billy Hayes' emotional first visit to the prison set.

Differences between the book and the film

Various aspects of Hayes' story were fictionalized or added to for the movie. Of note:

- In the movie, Billy Hayes is in Turkey with his girlfriend when he is arrested, whereas in the original story he is alone.

- Although Billy did spend seventeen days in the prison's psychiatric hospital in 1972, he never bit out anyone's tongue, which in the film led to him being committed to the section for the criminally insane.

- In the book's ending, Hayes was moved to another prison on an island from which he eventually escaped, by stealing a dinghy and rowing 17 miles in a raging storm across the Sea of Marmara, and then traveling by foot as well as on a bus to Istanbul and then crossing the border into Greece.[6] In the movie, this passage is replaced by a violent scene in which he unwittingly kills the head guard who is preparing to rape him. (In reality, Hamidou, the chief guard, was killed in 1973 by a recently paroled prisoner, who spotted him drinking tea at a café outside the prison and shot him eight times.) The attempted rape scene itself was fictionalized; Billy never claimed to have suffered any sexual violence at the hands of his Turkish wardens. He did engage in consensual sex while in prison, but the film depicts Hayes gently rejecting the advances of a fellow prisoner.

- There is a fleeting reference to The Pudding Shop in the bazaar. It was/is not there - it is on Divan Yolu.

Soundtrack

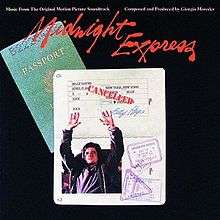

| Midnight Express: Music from the Original Motion Picture Soundtrack | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Soundtrack album by Giorgio Moroder | ||||

| Released | October 6, 1978 | |||

| Genre | Disco | |||

| Length | 37:00 | |||

| Label | Casablanca Records | |||

| Producer | Giorgio Moroder | |||

| Giorgio Moroder chronology | ||||

| ||||

Released on October 6, 1978, the soundtrack to Midnight Express was composed by Italian synth-pioneer Giorgio Moroder. The score won the Academy Award for Best Original Score in 1979.

Side A:

- "Chase" – Giorgio Moroder (8:24)

- "Love's Theme" – Giorgio Moroder (5:33)

- "(Theme From) Midnight Express" (Instrumental) – Giorgio Moroder (4:39)

Side B:

- "Istanbul Blues" (Vocal) – David Castle (3:17)

- "The Wheel" – Giorgio Moroder (2:24)

- "Istanbul Opening" – Giorgio Moroder (4:43)

- "Cacaphoney" – Giorgio Moroder (2:58)

- "(Theme From) Midnight Express" (Vocal) – Chris Bennett (4:47)

Reception

Midnight Express received both critical acclaim and box office success. On the film review aggregate site Rotten Tomatoes, 95% of film critics gave the film positive reviews, based on 20 reviews.[7]

Negative criticisms focused mainly on its unfavorable portrayal of Turkish people. In Mary Lee Settle's 1991 book Turkish Reflections, she writes, "The Turks I saw in Lawrence of Arabia and Midnight Express were like cartoon caricatures, compared to the people I had known and lived among for three of the happiest years of my life."[8] Pauline Kael, in reviewing the film, commented, "This story could have happened in almost any country, but if Billy Hayes had planned to be arrested to get the maximum commercial benefit from it, where else could he get the advantages of a Turkish jail? Who wants to defend Turks? (They don’t even constitute enough of a movie market for Columbia Pictures to be concerned about how they are represented)".[9] One reviewer writing for World Film Directors wrote, "Midnight Express is 'more violent, as a national hate-film than anything I can remember', 'a cultural form that narrows horizons, confirming the audience’s meanest fears and prejudices and resentments'".[10]

David Denby of New York criticized the film as "merely anti-Turkish, and hardly a defense of prisoners' rights or a protest against prison conditions".[11] Denby said also that all Turks in the movie – guardian or prisoner – were portrayed as "losers" and "swine" and that "without exception [all the Turks] are presented as degenerate, stupid slobs".[11]

Turkish Cypriot film director Derviş Zaim wrote a thesis at the University of Warwick on the representation of Turks in the film, where he concluded that the one-dimensional portrayal of the Turks as "terrifying" and "brutal" served merely to reinforce the sensational outcome and was likely influenced by such factors as Orientalism and Capitalism.[12]

Awards and nominations

Midnight Express won Academy Awards for Best Music, Original Score (Giorgio Moroder) and Best Writing, Screenplay Based on Material from Another Medium (Stone). It was also nominated for Best Actor in a Supporting Role (John Hurt), Best Director, Best Film Editing and Best Picture.

The film was also entered into the 1978 Cannes Film Festival.[13]

Legacy

There were instances in which days before U. S. Navy ships made ports of call in cities such as Izmir, and Antalya Turkey, the film would be shown to sailors on board as a cautionary tale of what could happen to them if they committed any type of crime, or misbehaved in any way. An amateur interview with Hayes appeared on YouTube,[14] recorded during the 1999 Cannes Film Festival, in which he described his experiences and expressed his disappointment with the film adaptation.[15] In an article for the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Hayes was reported as saying that the film "depicts all Turks as monsters."[16]

When he visited Turkey in 2004, screenwriter Oliver Stone, who won an Academy Award for the film, made an apology for the portrayal of the Turkish people in the film.[2] He "eventually apologized for tampering with the truth."[17]

Alan Parker, Oliver Stone and Billy Hayes were invited to attend a special film screening with prisoners in the garden of an L-type prison in Döşemealtı, Turkey, as part of the 47th Antalya Golden Orange Film Festival in October 2010.[18]

Dialogue from the film was sampled in the song Sanctified on the original version of Nine Inch Nails' debut album Pretty Hate Machine. The sample was removed from the 2010 remaster for copyright reasons.

Other dialogue was also sampled for and possibly inspired the song "Rifki" from :wumpscut:'s 2008 album "Schädling".

In 2016 Alan Parker returned to Malta as a special guest during the 2nd edition of the Valletta Film Festival to attend a screening of the film on 4 June at Fort St Elmo, where many of the prison scenes were filmed.[5]

References

- ↑ "Midnight Express, Box Office Information". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved January 27, 2012.

- 1 2 Smith, Helena (16 December 2004). "Stone sorry for Midnight Express". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- ↑ Flinn, John (9 January 2004). "The real Billy Hayes regrets 'Midnight Express' cast all Turks in a bad light". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- ↑ Fellner, Dan (2013). "Catching the Midnight Express in Malta". global-travel-info.com. Retrieved 23 June 2015.

- 1 2 Galea, Peter (1 June 2016). "A Valletta blockbuster". Times of Malta.

- ↑ http://www.manolith.com/2010/06/30/billy-hayes-and-the-real-midnight-express/

- ↑ Midnight Express. Rotten Tomatoes.

- ↑ Mary Lee Settle (1991). Turkish Reflections. New York: Prentice Hall Press. ISBN 0-13-917675-6.

- ↑ Pauline Kael (1980). When the Lights Go Down. New York: Hall Rinehart and Winston. ISBN 0-03-042511-5.

- ↑ John Wakeman(ed) (1988). World Film Directors. New York: T.H. W. Wilson Co.

- 1 2 Denby, D. (1978, October 16). One Touch of Mozart. New York Magazine, 11(42), 123.

- ↑ "Representation of the Turkish People in Midnight Express". Zaim, Dervis. Published in Örnek literary journal, 1994. A copy can be found at http://www.tallarmeniantale.com/MidExp-academic.htm

- ↑ "Festival de Cannes: Midnight Express". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 2009-05-20.

- ↑ Part 1 on YouTube, Part 2 on YouTube

- ↑ "Interview with Billy Hayes about 'Midnight Express' on YouTube". Youtube.com. Retrieved 2010-05-20.

- ↑ "The real Billy Hayes regrets 'Midnight Express' cast all Turks in a bad light – Seattle Post Intelligencer". Seattlepi.com. 2004-01-10. Retrieved 2010-05-20.

- ↑ Walsh, Caspar. The 10 best prison films. The Observer. May 30, 2010

- ↑ "'Midnight Express' team to watch film with Turkish prisoners". Hürriyet Daily News. 2010-05-20. Retrieved 2010-07-31.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Midnight Express (film) |

- Midnight Express at the Internet Movie Database

- Midnight Express at Rotten Tomatoes

- Script of movie by Oliver Stone (pdf)