Millbank Prison

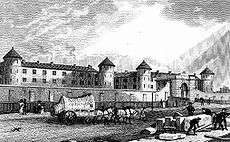

Millbank Prison was a prison in Millbank, Pimlico, London, originally constructed as the National Penitentiary, and which for part of its history served as a holding facility for convicted prisoners before they were transported to Australia. It was opened in 1816 and closed in 1890.

Construction

The site at Millbank was originally purchased in 1799 on behalf of the Crown by the philosopher Jeremy Bentham, for the erection of his Panopticon prison as Britain's new National Penitentiary. After various changes in circumstance, the Panopticon plan was abandoned in 1812. An architectural competition was then held for a new penitentiary design. It attracted 43 entrants, the winner being William Williams, drawing master at the Royal Military College, Sandhurst. Williams' basic design was adapted by a practising architect, Thomas Hardwick, who began construction in the same year. Hardwick resigned in 1813, and John Harvey took over the role. Harvey was dismissed in turn in 1815, and replaced by Robert Smirke, who brought the project to completion in 1821.[1]

The marshy site on which the prison stood meant that the builders experienced problems of subsidence from the outset (and explains the succession of architects). Smirke finally resolved the difficulty by introducing a highly innovative concrete raft to provide a secure foundation. However, this added considerably to the construction costs, which eventually totalled £500,000, more than twice the original estimate.

History

The first prisoners, all women, were admitted on 26 June 1816, the first men arriving in January 1817. The prison held 103 men and 109 women by the end of 1817, and 452 men and 326 women by late 1822. Sentences of five to ten years in the National Penitentiary were offered as an alternative to transportation to those thought most likely to reform.

In addition to the problems of construction, the marshy site fostered disease, to which the prisoners had little immunity owing to their extremely poor diet. In 1818 they employed a Medical Supervisor, in the form of Dr Alexander Copland Hutchison of Westminster Dispensary, to oversee the health issues of the occupants..[2] In 1822–23 an epidemic swept through the prison, which seems to have comprised a mixture of dysentery, scurvy, depression and other disorders.[3] The decision was eventually taken to evacuate the buildings for several months: the female prisoners were released, and the male prisoners temporarily transferred to the prison hulks at Woolwich (where their health improved).

The design also turned out to be unsatisfactory. The network of corridors was so labyrinthine that even the warders got lost; and the ventilation system allowed sound to carry, so that prisoners could communicate between cells. The annual running costs turned out to be an unsupportable £16,000.

In view of these problems, the decision was eventually taken to build a new "model prison" at Pentonville, which opened in 1842 and took over Millbank's role as the National Penitentiary. By an Act of Parliament of 1843, Millbank's status was downgraded, and it became a holding depot for convicts prior to transportation. Every person sentenced to transportation was sent to Millbank first, where they were held for three months before their final destination was decided. By 1850, around 4,000 people convicted of crimes were being transported annually from the UK.[1] Prisoners awaiting transportation were kept in solitary confinement and restricted to silence for the first half of their sentence.

Large-scale transportation ended in 1853 (although the practice continued on a reduced scale until 1867); and Millbank then became an ordinary local prison, and from 1870 a military prison. By 1886 it had ceased to hold inmates, and it closed in 1890.[4] Demolition began in 1892, and continued sporadically until 1903.

Description

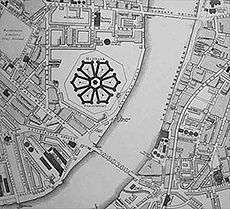

The plan of the prison comprised a circular chapel at the centre of the site, surrounded by a three-storey hexagon made up of the governor's quarters, administrative offices and laundries, surrounded in turn by six pentagons of cell blocks. The buildings of each pentagon were set around a cluster of five courtyards (with a watchtower at the centre) used as airing-yards, and in which prisoners undertook labour.[5] The three outer angles of each pentagon were distinguished by tall circular towers, described in 1862 as "Martello-like", and which served in part as watchtowers, but the primary purpose of which was to contain staircases and water-closets.[6][7] The third and fourth pentagons (those to the north-west, furthest from the entrance) were used to house female prisoners, and the remaining four for male prisoners.

In the Handbook of London in 1850 the prison was described as follows:

MILLBANK PRISON. A mass of brickwork equal to a fortress, on the left bank of the Thames, close to Vauxhall Bridge; erected on ground bought in 1799 of the Marquis of Salisbury, and established pursuant to 52 Geo. III., c. 44, passed Aug 20th, 1812. It was designed by Jeremy Bentham [factually incorrect], to whom the fee-simple of the ground was conveyed, and is said to have cost the enormous sum of half a million sterling. The external walls form an irregular octagon, and enclose upwards of sixteen acres of land. Its ground-plan resembles a wheel, the governor's house occupying a circle in the centre, from which radiate six piles of building, terminating externally in towers. The ground on which it stands is raised but little above the river, and was at one time considered unhealthy. It was first named "The Penitentiary," or "Penitentiary House for London and Middlesex," and was called "The Millbank Prison" pursuant to 6 & 7 of Victoria, c. 26. It is the largest prison in London. Every male and female convict sentenced to transportation in Great Britain is sent to Millbank previous to the sentence being executed. Here they remain about three months under the close inspection of the three inspectors of the prison, at the end of which time the inspectors report to the Home Secretary, and recommend the place of transportation. The number of persons in Great Britain and Ireland condemned to transportation every year amounts to about 4000. So far the accommodation of the prison permits, the separate system is adopted. Admission to inspect – order from the Secretary for the Home Department, or the Inspector of Prisons.

Each cell had a single window (looking into the pentagon courtyard), and was equipped with a washing tub, a wooden stool, a hammock and bedding, and books including a Bible, a prayer-book, a hymn-book, an arithmetic-book, a work entitled Home and Common Things, and publications of the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.[6]

Irish republican prisoner Michael Davitt, who was held briefly at Millbank in 1870, described the experience:

Westminster Clock is not far distant from the penitentiary, so that its every stroke is as distinctly heard in each cell as if it were situated in one of the prison yards. At each quarter of an hour, day and night it chimes a bar of the "Old Hundredth" and those solemn tones strike on the ears of the lonely listeners like the voice of some monster spirit singing the funeral dirge of Time.[8]

Later development of the site

As the prison was progressively demolished its site was redeveloped. The principal new buildings erected were the National Gallery of British Art (now Tate Britain), which opened in 1897; the Royal Army Medical School, the buildings of which were adapted in 2005 to become the Chelsea College of Art & Design; and – using the original bricks of the prison – the Millbank Estate, a housing estate built by the London County Council (LCC) between 1897 and 1902. The estate comprises 17 buildings, each named after a distinguished painter, and is Grade II listed.

Remains of the prison

A large circular bollard stands by the river with the inscription: "Near this site stood Millbank Prison which was opened in 1816 and closed in 1890. This buttress stood at the head of the river steps from which, until 1867, prisoners sentenced to transportation embarked on their journey to Australia."

Part of the perimeter ditch of the prison survives running between Cureton Street and John Islip Street: it is now used as a clothes-drying area for residents of Wilkie House.

The granite gate piers at the entrance of Purbeck House, High Street, Swanage in Dorset, and a granite bollard next to the gate, are believed by English Heritage to be from Millbank prison.[9]

Archaeological investigations in the late 1990s and early 2000s on the sites of Chelsea College of Art and Design and Tate Britain recorded significant remains of the foundations of the external pentagon walls of the prison, of parts of the inner hexagon, of two of the courtyard watchtowers, of drainage culverts, and of Smirke's concrete raft.[10][11]

Cultural references

In Henry James's realist novel The Princess Casamassima (1886) the prison is the "primal scene" of Hyacinth Robinson's life: the visit to his mother, dying in the infirmary, is described in chapter 3. James visited Millbank on 12 December 1884 to gain material.[12]

The prison is also evocatively described in Sarah Waters' 1999 novel Affinity.

Charles Dickens describes the prison in chapter 52 ("Obstinacy") of his novel, Bleak House (1852–3). One of the characters is put into custody there, and other characters go to visit him. Esther Summerson, one of the book's narrators, gives a brief description of its layout.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle in chapter 8 of The Sign of Four (1890) refers to Holmes and Watson crossing the Thames from the house of Mordecai Smith and landing by the Millbank Penitentiary.

See also

- List of demolished buildings and structures in London

- Convicts in Australia

- Penal transportation

- separate system

Notes

- 1 2 "Millbank Prison", Handbook of London, 1850.

- ↑ Parliamentary Papers 1780-1849 vol 5, 1825: The General Penitentiary at Milbank

- ↑ Evans 1982, p. 249.

- ↑ Brodie et al. 2002, p. 60.

- ↑ Griffiths 1875, p. 26.

- 1 2 Mayhew and Binny 1862.

- ↑ Holford 1828, plan of prison.

- ↑ Power, John O'Connor; Davitt, Michael (1878). Irish political prisoners: speeches of John O'Connor Power in the House of Commons on the subject of amnesty, &c., and a statement by Mr. Michael Davitt on prison treatment. London. p. 52.

- ↑ National Monuments Record, English Heritage, accessed September 22, 2009.

- ↑ Edwards 2007.

- ↑ Edwards 2010.

- ↑ Henry James letters, edited by Leon Edel, Vol. 3: 1883-1895, Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press; London: Macmillan, 1980, page 61.

Bibliography

- Brodie, Allan; Croom, Jane; Davies, James O. (2002). English Prisons: an architectural history. Swindon: English Heritage. ISBN 1-873592-53-1.

- Edwards, Catherine (2007). "The Millbank Penitentiary: excavations at the Chelsea School of Art and Design". London Archaeologist. 11.7: 177–83.

- Edwards, Catherine (2010). "The Millbank Penitentiary: excavations at the Tate Gallery (now Tate Britain), City of Westminster". Transactions of the London and Middlesex Archaeological Society. 61: 157–74.

- Evans, Robin (1982). The Fabrication of Virtue: English prison architecture, 1750–1840. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 244–250. ISBN 0521239559.

- Griffiths, Arthur George Frederick (1875). Memorials of Millbank, and Chapters in Prison History. 2 vols,. London: Beccles. (2 vols.)

- Holford, George Peter (1828). An Account of the General Penitentiary at Millbank. London.

- Mayhew, Henry; Binny, John (1862). The Criminal Prisons of London and Scenes of Prison Life. London. (Chapter 5).

- The Nuttall Encyclopaedia, "Millbank Prison".

- Thurley, Simon (2004). Lost Buildings of Britain. London: Viking. ISBN 0-670-91521-1.

External links

- Collection of Victorian references

- 1859 map - the penitentiary is the distinctive six-pointed building near the bottom

- Millbank Estate today

Coordinates: 51°29′29″N 0°07′44″W / 51.49139°N 0.12889°W