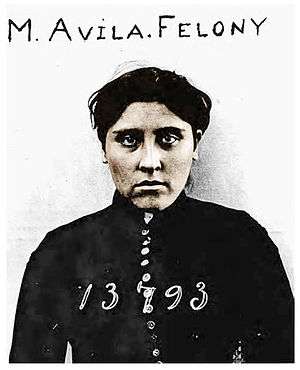

Modesta Avila

Modesta Ávila (1867 or 1869 – September 1891) was a protestor in Orange County, California who became the county's first convicted felon and first state prisoner.[1][2] Avila had only received a minor warning in 1889 for placing an obstruction on the tracks to protest against the Santa Fe Railroad being built through her property without adequate compensation, but she continued to taunt the authorities, and was eventually arrested four months later.

Although the jury in her first trial was unable to reach agreement, Avila was convicted after a second trial at Orange County Supreme Court and was sentenced to three years in San Quentin State Prison. She died there of pneumonia in September 1891 after serving two years and seven months of her sentence. Today Avila is considered to be a folk heroine of Latino people of the county, and is suggested as the "White Lady", a ghost said to haunt the area, reported to have been seen walking along the railroad tracks since the 1930s.

Background

Avila was born in 1867,[3] or 1869 according to some sources,[4] in San Juan Capistrano, in Orange County, California, located approximately 23 miles (37 km) southeast of Downtown Santa Ana. Little is known about her childhood and earlier life, but by the age of 20 she had inherited land from her mother just to the north of the Capistrano train station and was occupied in chicken rearing.[5] Physically Avila was described as a "dark-eyed beauty" in appearance and an "extremely proud woman".[5][6] The authorities would have considered her a Mexican even though she had been born in San Juan Capistrano and was technically a Mexican-American or Chicana; Mexicans were unpopular in the county at the time and subject to racism.[4][5][7] She had spent 30 days in Los Angeles County Jail in 1888 for "vagrancy" (often a euphemism for prostitution) and this, coupled with the fact that she was reportedly unmarried and pregnant at the time of her second trial, led to a belief that she supplemented her income by working as a prostitute.[1][5] The obituary in the Santa Ana Standard following her death in September 1891 seemed to add weight to this by referring to her as "a well-known favorite of the Santa Ana boys".[5]

Protest

Avila was upset by the construction of the Santa Fe Railroad through her family's land and only 15 feet away from her home, believing that she had not been properly compensated for the railway which was having a negative impact on her chicken rearing and her quality of life because of the noise.[6] In 1889, she decided to protest against the railroad's incursion into her life and property. Local sources say she tied a clothesline hung with her laundry across the track,[5][8] but other reports say she placed a railroad tie across the tracks and erected a fence post between the rails to which she attached a note of protest that read: "This land belongs to me. And if the railroad wants to run here, they will have to pay me ten thousand dollars".[1] Max Mendelson, the Southern Pacific's agent in San Juan Capistrano, reported that he had removed the post, informed Avila that the Southern Pacific were perfectly within their rights in the building of the railroad, and ordered her not to interfere again.[1]

There is some doubt over what occurred between Avila and Mendelson. Avila seemed to believe that she would be compensated, and is even documented to have traveled to a bank in Santa Ana to ask how she might receive a $10,000 payment and organized a party in celebration of her expected payment.[1][9] She was arrested at the party for disturbing the peace, and annoyed the authorities by boasting at her trial of her victory over the railroad company and government. According to historian Lisbeth Haas in the book Conquests and Historical Identities in California, 1769–1936, it was her actions after her initial protest rather than the act itself which led to her arrest four months later for "attempted obstruction of a train",[6][10] and that she was made an example of to demonstrate that protests would be punished under the new state legal system.[1]

Prosecution and imprisonment

The first trial of Avila for interfering with the tracks was held at the then newly opened Orange County Superior Court under Edward Eugenes, a "hot shot" legal figure who was also in the state assembly.[2][4] The first trial ended with a 6-6 hung jury.[5] In the week leading up to the retrial, rumors spread that Avila was pregnant out of wedlock, an act considered to be gravely sinful at the time.[2][5] Her lawyer, George Hayford, "inexperienced and probably crooked",[2] was forced to confirm that she was pregnant and believed that the real decision to incarcerate her for three years in San Quentin State Prison was largely due to this, writing that "her real crime is that she is a poor girl not having sense enough to have been married".[5] Hayford appealed to the court on grounds that she had been "convicted on her reputation, not her deed". He received a hearing at the Supreme Court, but lost the case on a technicality. Avila's case was perhaps also used as the "vehicle for polishing Orange County’s law-and-order image", as she was the first person to be convicted of a felony in the county.[11] Avila's boyfriend at the time was fired from his job for refusing to distance himself from her.[1]

If she was pregnant, what became of her baby is unknown: no mention of it appears in the penitentiary's records.[2] Avila died there of pneumonia in September 1891 at the age of 22 or 24 after serving two years and five months of her sentence.[2][5][6][12] Her obituary in the Santa Ana Standard concluded: "Let those who are without sin throw the first stone".[2]

Legacy

Today, Avila is considered to be an important figure in local legend and has been cited as a "folklore heroine" for Latinos in the county.[4] The San Juan Capistrano Historical Society unveiled a plaque in the town commemorating her and her place in history. Mary P. Nolan, executive director of the Central Orange County YWCA, included Avila among 30 prominent "women of courage" in Orange County's history.[5]

As part of the celebrations for the centenary of the building of the Santa Fe railroad in August 1988, a re-enactment of her protest was performed near the railway station by a local woman, Irma Camarena, and actors playing Mendelson and a sheriff.[5] City manager Steve Julian narrated: "Modesta hated the train. It was noisy, dirty and a bit frightening. It kept her chickens from laying eggs, and its whistle kept her awake at night. Plus, the powerful California Central, parent company to the Santa Fe, had paid a pittance to people for right of way through their property. Something had to be done. In an act of pure frustration, Modesta chose a symbolic act to voice her displeasure."[5]

Numerous writers on Latino oppression and history in the United States cite Avila as one of many Mexican-Americans victimized during this period. Suzanne Oboler, Professor of Latin American Studies at the City University of New York, for instance, considers the imprisonment of Avila and others such as Jimmy Santiago Baca, Ricardo Sánchez, Raúl Salinas, Fred Gómez Carrasco, Judy Lucero and Alvaro Luna Hernandez to be "inextricably linked to colonial domination and the subsequent struggle for material resources in the southwestern United States".[13] An opera entitled Modesta Avila: An American Folk Opera written by an Orange County biomedical engineer was performed in Westminster in 1986 but was dismissed as "neo-imperialist nostalgia" by B. V. Olguín in La Pinta: Chicana/o Prisoner Literature, Culture, and Politics.[14][15] The Modesta Avila Coalition, an activist group in the Los Angeles area involved with fighting against firms who transport goods to and from rail yards, named themselves after her in 2005.[16]

Avila is suggested as a possible identity for the ghost, known as the "White Lady", which has reputedly been seen in San Juan Capistrano's Los Rios Street Historic District. The ghost was first reported walking on the railway tracks in the 1930s, along the stretch that Avila had walked.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Brennan, Paul (30 October 2003). "The White Lady Was Brown 100 years ago, fighting the Southern Pacific could get you killed in OC". Orange County Weekly. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Orange Coast Magazine. Emmis Communications. February 1989. pp. 87–8. ISSN 0279-0483.

- ↑ Ruiz, Vicki L.; Korrol, Virginia Sánchez (3 May 2006). Latinas in the United States, set: A Historical Encyclopedia. Indiana University Press. pp. 70–. ISBN 0-253-11169-2.

- 1 2 3 4 Arellano, Gustavo (16 September 2008). Orange County: A Personal History. Simon and Schuster. p. 175. ISBN 978-1-4391-2320-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Emmons, Steve (August 22, 1988). "'In an act of pure frustration, Modesta chose a symbolic act to voice her displeasure.' : Act of Defiance Stops Them In Their Tracks". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Tryon, Don. "First Felon was Railroaded – story of Modesta Avila". sanjuancapistrano.net. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ↑ Acuña, Rodolfo (1996). Anything But Mexican: Chicanos in Contemporary Los Angeles. Verso. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-85984-031-3.

- ↑ Frank, L.; Hogeland, Kim (2007). First Families: A Photographic History of California Indians. Heyday. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-59714-013-3.

- ↑ Haas, Lisbeth (1995). Conquests and Historical Identities in California, 1769–1936. University of California Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-520-20704-2.

- ↑ Hallan-Gibson, Pamela; Tryon, Don; Tryon, Mary Ellen (2005). San Juan Capistrano. Arcadia Publishing. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-7385-3044-4.

- ↑ "Avila, Modesta" (PDF). Brooklyn College. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ↑ Chalquist, Craig (June 2008). Deep California: Images and Ironies of Cross and Sword on El Camino Real. Craig Chalquist, PhD. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-595-51462-5.

- ↑ Oboler, Suzanne (24 November 2009). Behind Bars: Latino/as and Prison in the United States. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 265–6. ISBN 978-0-230-10147-0.

- ↑ Olguín, B. V. (2010). "Toward a Materialist History of Chicana/o Criminality: Modesta Avila as Paradigmatic Pinta". La Pinta: Chicana/o Prisoner Literature, Culture, and Politics. University of Texas Press. pp. 37–64. ISBN 978-0-292-77885-6.

- ↑ Rasmussen, Cecilia (February 1, 2004). "Protester May Have Been Railroaded". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ Gottlieb, Robert (12 October 2007). Reinventing Los Angeles: Nature and Community in the Global City. MIT Press. p. 313. ISBN 978-0-262-26297-2.