Mughal painting

Mughal painting is a particular style of South Asian painting, generally confined to miniatures either as book illustrations or as single works to be kept in albums, which emerged from Persian miniature painting (itself largely of Chinese origin), with Indian Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist influences, and developed largely in the court of the Mughal Empire of the 16th to 18th centuries.

Mughal painting later spread to other Indian courts, both Muslim and Hindu, and later Sikh. The mingling of foreign Persian and indigenous Indian elements was a continuation of the patronisation of other aspects of foreign culture as initiated by the earlier Turko-Afghan Delhi Sultanate, and the introduction of it into the subcontinent by various Central Asian Turkic dynasties, such as the Ghaznavids.

Origins

This art of painting developed as a blending of Persian and Indian ideas. There was already a Muslim tradition of miniature painting under the Turko-Afghan Sultanate of Delhi which the Mughals overthrew, and like the Mughals, and the very earliest of Central Asian invaders into the subcontinent, patronized foreign culture. Although the first surviving manuscripts are from Mandu in the years either side of 1500, there were very likely earlier ones which are either lost, or perhaps now attributed to southern Persia, as later manuscripts can be hard to distinguish from these by style alone, and some remain the subject of debate among specialists.[1] By the time of the Mughal invasion, the tradition had abandoned the high viewpoint typical of the Persian style, and adopted a more realistic style for animals and plants.[2]

No miniatures survive from the reign of the founder of the dynasty, Babur, nor does he mention commissioning any in his diaries, the Baburnama. Copies of this were illustrated by his descendents, Akbar in particular, with many portraits of the many new animals Babur encountered when he invaded India, which are carefully described.[3] However some surviving un-illustrated manuscripts may have been commissioned by him, and he comments on the style of some famous past Persian masters. Some older illustrated manuscripts have his seal on them; the Mughals came from a long line stretching back to Timur and were fully assimilated into Persianate culture, and expected to patronize literature and the arts.

Mughal painting immediately took a much greater interest in realistic portraiture than was typical of Persian miniatures. Animals and plants were also more realistically shown. Although many classic works of Persian literature continued to be illustrated, as well as Indian works, the taste of the Mughal emperors for writing memoirs or diaries, begun by Babur, provided some of the most lavishly decorated texts, such as the Padshahnama genre of official histories. Subjects are rich in variety and include portraits, events and scenes from court life, wild life and hunting scenes, and illustrations of battles. The Persian tradition of richly decorated borders framing the central image was continued.

The style of the Mughal school developed within the royal atelier. Knowledge was primarily transmitted through familial and apprenticeship relationships, and the system of joint manuscript production which brought multiple artists together for single works.[4]

Development

Humayun

When the second Mughal emperor, Humayun (reigned 1530–40 and 1555–56) was in exile in Tabriz in the Safavid court of Shah Tahmasp I of Persia, he was exposed to Persian miniature painting, and commissioned at least one work there, an unusually large painting of Princes of the House of Timur, now in the British Museum. When Humayun returned to India, he brought with him two accomplished Persian artists Abd al-Samad and Mir Sayyid Ali. His usurping brother Kamran Mirza had maintained a workshop in Kabul, which Humayan perhaps took over into his own. Humayan's major known commission was a Khamsa of Nizami with 36 illuminated pages, in which the different styles of the various artists are mostly still apparent.[5] Apart from the London painting, he also commissioned at least two miniatures showing himself with family members,[6] a type of subject that was rare in Persia but was to be common among the Mughals.[7]

Mughal painting developed and flourished during the reigns of Akbar, Jahangir and Shah Jahan.

Akbar

During the reign of Humayun's son Akbar (r. 1556-1605), the imperial court, apart from being the centre of administrative authority to manage and rule the vast Mughal empire, also emerged as a centre of cultural excellence. Akbar inherited and expanded his father's library and atelier of court painters, and paid close personal attention to its output. He had studied painting in his youth under Abd as-Samad, though it is not clear how far these studies went.[8]

Between 1560 and 1566 the Tutinama ("Tales of a Parrot"), now in the Cleveland Museum of Art was illustrated, showing "the stylistic components of the imperial Mughal style at a formative stage".[9] Among other manuscripts, between 1562 and 1577 the atelier worked on an illustrated manuscript of the Hamzanama consisting of 1,400 canvas folios. Sa'di's masterpiece The Gulistan was produced at Fatehpur Sikri in 1582, a Darab Nama around 1585; the Khamsa of Nizami (British Library, Or. 12208) followed in the 1590s and Jami's Baharistan around 1595 in Lahore. As Mughal-derived painting spread to Hindu courts the texts illustrated included the Hindu epics including the Ramayana and the Mahabharata; themes with animal fables; individual portraits; and paintings on scores of different themes. Mughal style during this period continued to refine itself with elements of realism and naturalism coming to the fore. Between the years of 1570 to 1585 Akbar hired over a one hundred painters to practice Mughal style painting.[10]

Jahangir (1605–25)

Jahangir had an artistic inclination and during his reign Mughal painting developed further. Brushwork became finer and the colors lighter. Jahangir was also deeply influenced by European painting. During his reign he came into direct contact with the English Crown and was sent gifts of oil paintings, which included portraits of the King and Queen. He encouraged his royal atelier to take up the single point perspective favoured by European artists, unlike the flattened multi-layered style used in traditional miniatures. He particularly encouraged paintings depicting events of his own life, individual portraits, and studies of birds, flowers and animals. The Jahangirnama, written during his lifetime, which is an autobiographical account of Jahangir's reign, has several paintings, including some unusual subjects such as the union of a saint with a tigress, and fights between spiders.

Shah Jahan (1628–59)

During the reign of Shah Jahan (1628–58), Mughal paintings continued to develop, but they gradually became cold and rigid. Themes including musical parties; lovers, sometimes in intimate positions, on terraces and gardens; and ascetics gathered around a fire, abound in the Mughal paintings of this period.[11]

Later paintings

Aurangzeb (1658-1707) did not actively encourage Mughal paintings, but as this art form had gathered momentum and had a number of patrons, Mughal paintings continued to survive, but the decline had set in. Some sources however note that a few of the best Mughal paintings were made for Aurangzeb, speculating that the pathat he was about to close the workshops and thus exceeded themselves in his behalf.[12] A brief revival was noticed during the reign of Muhammad Shah 'Rangeela' (1719–48), but by the time of Shah Alam II (1759–1806), the art of Mughal painting had lost its glory. By that time, other schools of Indian painting had developed, including, in the royal courts of the Rajput kingdoms of Rajputana, Rajput painting and in the cities ruled by the British East India Company, the Company style under Western influence.

Artists

The Persian master artists Abd al-Samad and Mir Sayyid Ali, who had accompanied Humayun to India in the 16th century, were in charge of the imperial atelier during the formative stages of Mughal painting. Many artists worked on large commissions, the majority of them apparently Hindu, to judge by the names recorded. Mughal painting flourished during the late 16th and early 17th centuries with spectacular works of art by master artists such as Basawan, Lal, Daswanth,[13] and Miskin. Another influence on the evolution of style during Akbar's reign was Kesu Das, who understood and developed "European techniques of rendering space and volume".[14]

Govardhan was a noted painter during the reigns of Akbar, Jahangir and Shah Jahan.

The sub-imperial school of Mughal painting included artists such as Mushfiq, Kamal, and Fazl.

During the first half of the 18th century, many Mughal-trained artists left the imperial workshop to work at Rajput courts. These include artists such as Bhawanidas and his son Dalchand.

Mughal painting generally involved a group of artists, one to decide the composition, the second to actually paint, and the third to focus on portraiture, executing individual faces.[15]

Mughal style today

Mughal-style miniature paintings are still being created today by a small number of artists in Lahore concentrated mainly in the National College of Arts. Although many of these miniatures are skillful copies of the originals, some artists have produced contemporary works using classic methods with, at times, remarkable artistic effect.

The skills needed to produce these modern versions of Mughal miniatures are still passed on from generation to generation, although many artisans also employ dozens of workers, often painting under trying working conditions, to produce works sold under the signature of their modern masters.

Gallery

Portrait of Akbar

Portrait of Akbar Portrait of Bahadur Shah

Portrait of Bahadur Shah A noble lady, Mughal dynasty, India. 17th century. Color and gold on paper. Freer Gallery of Art F1907.219

A noble lady, Mughal dynasty, India. 17th century. Color and gold on paper. Freer Gallery of Art F1907.219 A Mughal prince and ladies in a garden

A Mughal prince and ladies in a garden

Shah Jahan on a terrace holding a pendant set with his portrait

Shah Jahan on a terrace holding a pendant set with his portrait-_Da'ud_Receives_a_Robe_of_Honor_from_Mun'im_Khan_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

A Mughal tournament

A Mughal tournament Victory of Ali Quli Khan on the river Gomti-Akbarnama, 1561

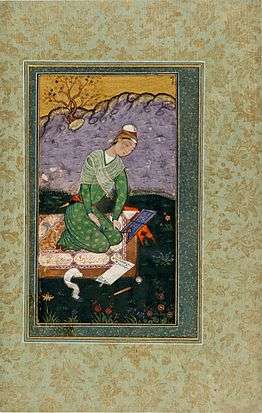

Victory of Ali Quli Khan on the river Gomti-Akbarnama, 1561 Mir Sayyid Ali's depiction of a young scholar in the Mughal Empire, reading and writing a commentary on the Quran, 1559.

Mir Sayyid Ali's depiction of a young scholar in the Mughal Empire, reading and writing a commentary on the Quran, 1559. The scribe and painter of the Khamsa of Nizami manuscript for Akbar

The scribe and painter of the Khamsa of Nizami manuscript for Akbar Battle scene from the Hamzanama of Akbar, 1570

Battle scene from the Hamzanama of Akbar, 1570

.jpg) Akbar riding the elephant Hawa'I pursuing another elephant across a collapsing bridge of boats (right), 1561

Akbar riding the elephant Hawa'I pursuing another elephant across a collapsing bridge of boats (right), 1561 Pir Muhammad Drowns While Crossing the Narbada-Akbarnama, 1562

Pir Muhammad Drowns While Crossing the Narbada-Akbarnama, 1562 Akbar receiving his sons at Fatehpur Sikri. Akbarnama, 1573

Akbar receiving his sons at Fatehpur Sikri. Akbarnama, 1573 Lion at rest Met

Lion at rest Met A young woman playing a Veena to a parakeet, a symbol of her absent lover. 18th-century painting in the provincial Mughal style of Bengal

A young woman playing a Veena to a parakeet, a symbol of her absent lover. 18th-century painting in the provincial Mughal style of Bengal Female performer with a tanpura, 18th century. Color and gold on paper. Freer Gallery of Art F1907.195

Female performer with a tanpura, 18th century. Color and gold on paper. Freer Gallery of Art F1907.195 Ascetic Seated on Leopard's Skin, late 18th century

Ascetic Seated on Leopard's Skin, late 18th century Mughal Ganjifa Playing Cards, Early 19th century, with miniature paintings - courtesy of the Wovensouls collection

Mughal Ganjifa Playing Cards, Early 19th century, with miniature paintings - courtesy of the Wovensouls collection

See also

- Persian miniature

- Ottoman miniature

- Indian painting

- Tanjore painting

- Rajput painting

- Madhubani painting

- Mushfiq, a sub-imperial Mughal painter

Notes

- ↑ Titley, 161-166

- ↑ Titley, 161

- ↑ Titley, 187

- ↑ Sarafan, Greg (6 November 2011). "Artistic Stylistic Transmission in the Royal Mughal Atelier". Sensible Reason.

- ↑ Grove

- ↑ Grove

- ↑ Beach, 58

- ↑ Beach, 49

- ↑ Grove

- ↑ Eastman

- ↑ Britannica

- ↑ Commentary by Stuart Cary Welch

- ↑ Diamind, Maurice. "Mughal Painting Under Akbar the Great" Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ↑ Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila S. (2009). The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. 1. Oxford University Press. p. 380. ISBN 978-0-19-530991-1.

- ↑ Britannica

- ↑ Basawan & Chitra (c.1590-95). "The Submission of the rebel brothers Ali Quli and Bahadur Khan-Akbarnama". Akbarnama. Check date values in:

|date=(help)

References

- Beach, Milo Cleveland, Early Mughal painting, Harvard University Press, 1987, ISBN 0-674-22185-0, ISBN 978-0-674-22185-7

- Eastman, Alvan C. "Mughal painting." College Art Association . 3.2 (1993): 36. Web. 30 Sep. 2013.

- "Grove", Oxford Art Online, "Indian sub., §VI, 4(i): Mughal ptg styles, 16th–19th centuries", restricted access.

- "Mughal Painting." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Academic Online Edition. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2013.Web. 30 Sep 2013.

- Titley, Norah M., Persian Miniature Painting, and its Influence on the Art of Turkey and India, 1983, University of Texas Press, 0292764847

- Sarafan, Greg, "Artistic Stylistic Transmission in the Royal Mughal Atelier", Sensible Reason, LLC, 2007, SensibleReason.com

Further reading

- Kossak, Steven. (1997). Indian court painting, 16th-19th century. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0870997831

- Painting for the Mughal Emperor (The Art of the Book 1560-1660) by Susan Stronge (ISBN 0-8109-6596-8)

- Fiction in Mughal Miniature Painting by Prof. P. C. Jain and Dr. Daljeet

- Painting the Mughal Experience by Som Prakash Verma, 2005 (ISBN 0-19-566756-5)

- Chitra, Die Tradition der Miniaturmalerei in Rajasthan by K.D. Christof & Renate Haass, 1999 (ISBN 978-3-89754-231-0)

- Welch, Stuart Cary; et al. (1987). The Emperors' album: images of Mughal India. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0870994999.

- Welch, Stuart Cary (1985). India: art and culture, 1300-1900. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9780944142134.

- Artistic Stylistic Transmission in the Royal Mughal Atelier by Greg Sarafan, J.D., 2007

External links

- Indian Court Painting, 16th-19th Century from the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- National Museum, Delhi - Mughal paintings

- San Diego Museum of Art

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mughal miniatures. |