Multiple-prism dispersion theory

The first description of multiple-prism arrays, and multiple-prism dispersion, was given by Newton in his book Opticks.[1] Prism pair expanders were introduced by Brewster in 1813.[2] A modern mathematical description of the single-prism dispersion was given by Born and Wolf in 1959.[3] The generalized multiple-prism dispersion theory was introduced by Duarte and Piper[4][5] in 1982.

Generalized multiple-prism dispersion equations

The generalized mathematical description of multiple-prism dispersion, as a function of the angle of incidence, prism geometry, prism refractive index, and number of prisms, was introduced as a design tool for multiple-prism grating laser oscillators by Duarte and Piper,[4][5] and is given by

which can also be written as

using

Also,

Here, is the angle of incidence, at the mth prism, and its corresponding angle of refraction. Similarly, is the exit angle and its corresponding angle of refraction. The two main equations give the first order dispersion for an array of m prisms at the exit surface of the mth prism. The plus sign in the second term in parentheses refers to a positive dispersive configuration while the minus sign refers to a compensating configuration.[4][5] The k factors are the corresponding beam expansions, and the H factors are additional geometrical quantities. It can also be seen that the dispersion of the mth prism depends on the dispersion of the previous prism (m - 1).

These equations can also be used to quantify the angular dispersion in prism arrays, as described in Isaac Newton's book Opticks, and as deployed in dispersive instrumentation such as multiple-prism spectrometers. A comprehensive review on practical multiple-prism beam expanders and multiple-prism angular dispersion theory, including explicit and ready to apply equations (engineering style), is given by Duarte.[7]

More recently, the generalized multiple-prism dispersion theory has been extended to include positive and negative refraction.[8] Also, higher order phase derivatives have been derived using a Newtonian iterative approach.[9] This extension of the theory enables the evaluation of the Nth higher derivative via an elegant mathematical framework. Applications include further refinements in the design of prism pulse compressors and nonlinear optics.

Single prism dispersion

For a single generalized prism (m = 1), the generalized multiple-prism dispersion equation simplifies to[3][10]

If the single prism is a right-angled prism with the beam exiting normal to the output face, that is equal to zero, this equation reduces to[7]

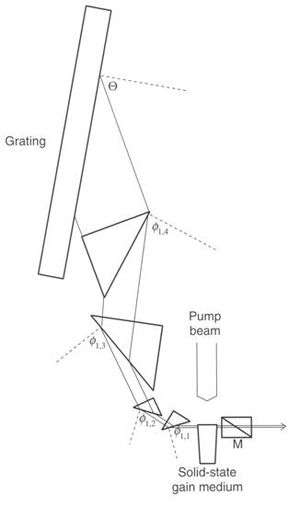

Intracavity dispersion and laser linewidth

The first application of this theory was to evaluate the laser linewidth in multiple-prism grating laser oscillators.[4] The total intracavity angular dispersion plays an important role in the linewidth narrowing of pulsed tunable lasers through the equation[4][7]

where is the beam divergence and the overall intracavity angular dispersion is the quantity in parentheses (elevated to –1). Although originally classical in origin, in 1992 it was shown that this laser cavity linewidth equation can also be derived from interferometric quantum principles.[11]

For the special case of zero dispersion from the multiple-prism beam expander, the single-pass laser linewidth is given by[7][10]

where M is the beam magnification provided by the beam expander that multiplies the angular dispersion provided by the diffraction grating. In practice, M can be as high as 100-200.[7][10]

When the dispersion of the multiple-prism expander is not equal to zero, then the single-pass linewidth is given by[4][7]

where the first differential refers to the angular dispersion from the grating and the second differential refers to the overall dispersion from the multiple-prism beam expander (given in the section above).[7][10]

Further applications

In 1987 the multiple-prism angular dispersion theory was extended to provide explicit second order equations directly applicable to the design of prismatic pulse compressors.[12] The generalized multiple-prism dispersion theory is applicable to:

- Amici prisms[13][14]

- laser microscopy,[15][16]

- narrow-linewidth tunable laser design,[17]

- prismatic beam expanders[4][5]

- prism compressors for femtosecond pulse lasers.[18][19][20]

See also

References

- ↑ I. Newton, Opticks (Royal Society, London, 1704).

- ↑ D. Brewster, A Treatise on New Philosophical Instruments for Various Purposes in the Arts and Sciences with Experiments on Light and Colours (Murray and Blackwood, Edinburgh, 1813).

- 1 2 M. Born and E. Wolf, Principles of Optics, 7th Ed. (Cambridge University, Cambridge, 1999).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 F. J. Duarte and J. A. Piper, "Dispersion theory of multiple-prism beam expanders for pulsed dye lasers", Opt. Commun. 43, 303–307 (1982).

- 1 2 3 4 F. J. Duarte and J. A. Piper, "Generalized prism dispersion theory", Am. J. Phys. 51, 1132–1134 (1982).

- ↑ F. J. Duarte, T. S. Taylor, A. Costela, I. Garcia-Moreno, and R. Sastre, Long-pulse narrow-linewidth disperse solid-state dye laser oscillator, Appl. Opt. 37, 3987-3989 (1998).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 F. J. Duarte, Tunable Laser Optics (Elsevier Academic, New York, 2003) Chapter 4.

- ↑ F. J. Duarte, Multiple-prism dispersion equations for positive and negative refraction, Appl. Phys. B 82, 35-38 (2006).

- ↑ F. J. Duarte, Generalized multiple-prism dispersion theory for laser pulse compression: higher order phase derivatives, Appl. Phys. B 96, 809-814 (2009).

- 1 2 3 4 F. J. Duarte, Narrow-linewidth pulsed dye laser oscillators, in Dye Laser Principles (Academic, New York, 1990) Chapter 4.

- ↑ F. J. Duarte, Cavity dispersion equation: a note on its origin, Appl. Opt. 31, 6979-6982 (1992).

- ↑ F. J. Duarte, "Generalized multiple-prism dispersion theory for pulse compression in ultrafast dye lasers", Opt. Quantum Electron. 19, 223–229 (1987)

- ↑ F. J. Duarte, Tunable organic dye lasers: physics and technology of high-performance liquid and solid-state narrow-linewidth oscillators, Progress in Quantum Electronics 36, 29-50 (2012).

- ↑ F. J. Duarte, Tunable laser optics: applications to optics and quantum optics, Progress in Quantum Electronics 37, 326-347 (2013).

- ↑ B. A. Nechay, U. Siegner, M. Achermann, H. Bielefeldt, and U. Keller, Femtosecond pump-probe near-field optical microscopy, Rev. Sci. Instrum. 70, 2758-2764 (1999).

- ↑ U. Siegner, M. Achermann, and U. Keller, Spatially resolved femtosecond spectroscopy beyond the diffraction limit, Meas. Sci. Technol. 12, 1847-1857 (2001).

- ↑ F. J. Duarte, Tunable Laser Optics, 2nd Edition (CRC, New York, 2015) Chapter 7.

- ↑ L. Y. Pang, J. G. Fujimoto, and E. S. Kintzer, Ultrashort-pulse generation from high-power diode arrays by using intracavity optical nonlinearities, Opt. Lett. 17, 1599-1601 (1992).

- ↑ K. Osvay, A. P. Kovács, G. Kurdi, Z. Heiner, M. Divall, J. Klebniczki, and I. E. Ferincz, Measurement of non-compensated angular dispersion and the subsequent temporal lengthening of femtosecond pulses in a CPA laser, Opt. Commun. 248, 201-209 (2005).

- ↑ J. C. Diels and W. Rudolph, Ultrashort Laser Pulse Phenomena, 2nd Ed. (Elsevier Academic, New York, 2006).