Myles Standish Burial Ground

|

Standish grave site at Myles Standish Burial Ground | |

| Details | |

|---|---|

| Established | c. 1638 |

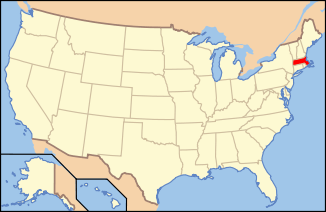

| Location | Duxbury, Massachusetts |

| Country | United States |

| Coordinates | 42°1′30.48″N 70°41′14.79″W / 42.0251333°N 70.6874417°W |

| Size | 1.5-acre (0.61 ha) |

| Number of graves | Approx. 130 |

| Website | Standish Burial Ground |

| Find a Grave | Myles Standish Burial Ground |

The Myles Standish Burial Ground (also known as Old Burying Ground or Standish Cemetery) in Duxbury, Massachusetts is, according to the American Cemetery Association, the oldest maintained cemetery in the United States.

The 1.5-acre (0.61 ha) burying ground is the final resting place of several well-known Pilgrims who arrived on the Mayflower in 1620, including Captain Myles Standish. The site was the location of Duxbury's first meeting house.[1] It was in use from approximately 1638 until 1789 at which point the cemetery was abandoned. It was reclaimed in 1887 by the Duxbury Rural Society, generating a widespread interest in locating the resting place of Duxbury's most famous colonist, Myles Standish. After two exhumations in 1889 and 1891, it was generally agreed that Standish's remains had been located and a memorial was built over his grave site.[2] The Standish grave site memorial is today the most prominent feature in the burying ground.

The burying ground is now owned and maintained by the Town of Duxbury. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2015.

History

Original use

Duxbury was settled by inhabitants of Plymouth Colony in 1627. In that year, the first land division was held and the shoreline of the present-day towns of Plymouth, Duxbury and Marshfield was divided into farmsteads. The families who settled in Duxborough, as it was then called, petitioned in 1632 to be set off as a separate town. The petition was granted in 1637 and Duxbury was permitted to build its own meeting house.[3] The meeting house was constructed on a knoll overlooking an inlet of Plymouth Bay known as Morton's Hole. The small path that once ran alongside it is now a modern road known as Chestnut Street. The town's first burying ground was located adjacent to the original meeting house. A stone marker within the burying ground designates the approximate location of the first meeting house.[4]

With the meeting house in place by 1638, the burying ground came into use shortly thereafter. The earliest graves were marked with simple fieldstones or wooden markers that have since deteriorated or vanished.[5] It is believed that most of Duxbury's 17th century residents were interred within the burying ground, however, due to the lack of markers, their exact resting places are unknown. The oldest extant carved gravestone in the cemetery is that of Captain Jonathan Alden, who died in 1697.[6] He was the youngest child of Mayflower passengers John Alden and Priscilla Mullins Alden.

The second oldest grave is that of Rev. Ichabod Wiswall, who was the second pastor of the Duxbury church from 1676 until his death in 1700. Wiswall was part of a three-man delegation, including Rev. Increase Mather, sent to London in 1691 to petition for a new charter for Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth Colonies. This effort resulted in the 1692 charter which established the Province of Massachusetts Bay, merging the two colonies.[7]

In all, there are approximately 130 marked graves in the cemetery.[8] Tradition suggests that there were once many more and, according to a 19th-century Duxbury resident, it was once possible to "jump from stone to stone from one side of the graveyard to the other."[9] With the disappearance of many stones, the existing markers are now sparsely scattered. The surviving gravestones date mostly from the 1760s and the 1770s. Only 34 stones pre-date 1750.[10]

Around 1707, the Town constructed a second meeting house "three or four rods," about 50 to 66 feet or 15 to 20 metres, to the east of the original meeting house.[11] A stone marker indicates the approximate location of the second meeting house which stood from c. 1707 to 1786 on a 0.5-acre (0.20 ha) lot adjacent to the burying ground. In 2008, the Duxbury Rural and Historical Society undertook an archaeological dig, locating the remains of the second meeting house foundation.[12] When the second meeting house became outdated, the town elected in 1785 to build a third meeting house in a location about 0.75 miles (1.21 km) from the Old Burying Ground. A new cemetery, now known as the Mayflower Cemetery, was established next to the new meeting house on Tremont Street. Consequently, the Old Burying Ground fell out of use by 1789.[13]

Neglect and rediscovery

In time, the original burying ground of Duxbury's first settlers became overgrown and all but forgotten. Cattle strayed over the burying ground and thick brush obscured many of the markers for most of the 19th century.[14] With the publication of The Courtship of Miles Standish by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in 1858, New Englanders began to take an increased interest in Pilgrim history.[15] Duxbury, then suffering an economic slump after the loss of the shipbuilding industry, suddenly saw new business in the form of tourism. The Old Burying Ground became the focus of new attention in the late 19th century as the community sought to explore and reclaim its colonial past.[16]

In 1887, the Duxbury Rural Society (now the Duxbury Rural and Historical Society), which had been established a few years earlier to improve and beautify the town, embarked on a major project of reclaiming the Old Burying Ground. Brush was removed, gravestones repaired and a fence built around the cemetery to ward off cattle.[17] The burying ground has been maintained as a local historic site ever since.

Myles Standish grave site

As interest in the Old Burying Ground increased during the late 19th century, visitors to Duxbury frequently inquired after the grave site of Captain Myles Standish, leader of the Pilgrim militia and one of the first settlers of Duxbury. In the 1880s, there was considerable debate as to the final resting place of Capt. Standish.[18] After much research, it was generally agreed that Standish was buried beneath two pyramidal fieldstones in the center of the Old Burying Ground. To determine for certain whether the strange stones in fact marked the Standish family plot, the Duxbury Rural Society decided to exhume the graves beneath the stones in 1889. The project was controversial and proceeded only after lengthy debate.[19] In the course of the exhumation, the skeleton of an elderly male and a young woman were discovered. A newspaper reporter present for the exhumation wrote that, "nothing definite came of the effort" and the remains were re-interred.[20]

In 1890, Rev. Eugene J.V. Huiginn came to Duxbury as a new minister of the local Episcopal Church. An avid antiquarian, Huiginn was fascinated by Pilgrim history and disappointed to find that the graves of the earliest settlers could not be decisively located.[21] He came to the conclusion that the 1889 exhumation had not adequately investigated the site and should have opened more graves. Huiginn obtained permission from the Town of Duxbury to open the graves again and, on April 25 and May 12, 1891, Huiginn and a small team excavated two different portions of the purported Standish burial plot.[22]

In the course of the 1891 investigation, the graves of four individuals were uncovered: an elderly man alleged by Huiginn to be Myles Standish, two adult women alleged to be Lora Standish (Myles Standish's daughter) and Mary Dingley Standish (Myles Standish's daughter-in-law), and a boy conjectured to be either Charles or John Standish (Myles Standish's sons) who both died young. A physician, Dr. Wilfred G. Brown of Duxbury, was present and was able to identify the gender and age at death of the subjects. These apparent ages were consistent with the historical death records of the above-mentioned members of the Standish family. These consistencies were Huiginn's primary evidence in identifying the remains of Myles Standish.[23] Other evidence included the burial of the elderly male between the two women, consistent with the fact that Standish, in his will, requested to be buried between his daughter and daughter-in-law.[24] Measurements and photographs were taken of the remains and Myles Standish was re-interred in a new pine coffin.

Huiginn led an effort, following this project, to have a substantial memorial placed over the Standish family plot. Constructed in 1893, the memorial is built around the two, small pyramidal stones which originally marked the plot and consists of a castellated stone wall with cannons mounted on each corner. Three large boulders bear the names of Myles Standish, Lora Standish and Mary Dingley Standish. The cannons, dating to 1853, were purchased from the Boston Navy Yard.

There would be a third exhumation of the remains of Myles Standish. Some of his descendants, unhappy with the fact that Standish had been re-interred in a pine coffin, requested the construction of a vault beneath the memorial to better preserve their ancestor's remains.[25] In 1931, they were granted permission by the Town to excavate the site. On this occasion there was a very large crowd present. Standish's remains were placed in a copper box, which in turn was placed in a cement chamber beneath the memorial. A copper tube containing time capsule material was also placed within the chamber.[26]

20th century markers

In 1930, the Alden Kindred of America, a non-profit organization composed of descendants of John and Priscilla Alden, placed slate gravestones to mark the approximate location of the resting places of John Alden, who died in 1687, and Priscilla Mullins Alden, who died around 1680. The markers were erected close to other Alden family stones, including that of their son Jonathan Alden, presuming that John and Priscilla were buried nearby.[27]

Descendants of George Soule, another passenger of the Mayflower, placed a marker in 1971 at the supposed location of Soule's grave, near other Soule family markers.

In 1977, the American Cemetery Association placed a plaque at the entrance to the burying ground proclaiming it, "The Oldest Maintained Cemetery in the United States."

Notable burials

- John Alden, Pilgrim

- Priscilla Alden, Pilgrim

- George Soule, Pilgrim

- Myles Standish, Pilgrim

- Ichabod Wiswall, third minister of Duxbury church

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Myles Standish Burial Ground. |

- Burial Hill

- Cole's Hill

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Plymouth County, Massachusetts

References

- ↑ Huiginn, Eugene Joseph Vincent The Graves of Myles Standish and Other Pilgrims (1892) (accessed July 18, 2009 on Google Books).

- ↑ Browne, Patrick T.J. and Forgit, Norman R. Duxbury...Past and Present. Duxbury: Duxbury Rural and Historical Society (2009), 38.

- ↑ Winsor, Justin. History of the Town of Duxbury. Boston: Crosby & Nichols (1849), 173.

- ↑ Wentworth, Dorothy. Settlement and Growth of Duxbury, 1628-1870. Duxbury: Duxbury Rural and Historical Society (2000) 3rd edition, 20.

- ↑ Pillsbury, Katherine H. Duxbury, A Guide. Duxbury: Duxbury Rural and Historical Society (1999), 34.

- ↑ Pillsbury, 36.

- ↑ Winsor, 113.

- ↑ "Standish Burial Grounds Decedent Locator". Town of Duxbury Cemetery Department. Retrieved January 22, 2010.

- ↑ Wentworth, 22.

- ↑ "Standish Burial Grounds Decedent Locator". Retrieved January 22, 2010.

- ↑ Wentworth, 21.

- ↑ "Archaeological Dig a Great Success" (PDF). The Lamplighter: The Newsletter of the Duxbury Rural and Historical Society. Fall 2008. Retrieved January 22, 2010.

- ↑ "Standish Burial Grounds Decedent Locator". Retrieved January 22, 2010.

- ↑ Browne and Forgit, 38.

- ↑ Pillsbury, 37.

- ↑ Pillsbury, 37.

- ↑ Browne and Forgit, 38.

- ↑ Huiginn, Eugene Joseph Vincent. The Graves of Myles Standish and Other Pilgrims. Beverly: Published by the author (1914), 14.

- ↑ Browne and Forgit, 40-41.

- ↑ Huiginn, 119.

- ↑ Huiginn, 14.

- ↑ Huiginn, 121.

- ↑ Huiginn, 130-145.

- ↑ Huiginn, 194.

- ↑ Browne and Forgit, 41.

- ↑ Browne and Forgit, 41.

- ↑ Pillsbury, 36

Images

Myles Standish's skull discovered in the Standish gravesite at Myles Standish Burial Ground during an investigation of the grave

Myles Standish's skull discovered in the Standish gravesite at Myles Standish Burial Ground during an investigation of the grave Myles Standish grave in 1914

Myles Standish grave in 1914- Myles Standish grave

- John Alden and Priscilla Alden graves

- George Soule grave

External links

Coordinates: 42°01′30″N 70°41′15″W / 42.02513°N 70.68739°W