National Institute of Standards and Technology

|

| |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 1901 (as National Bureau of Standards) |

| Headquarters | Gaithersburg, Maryland, U.S. |

| Annual budget | $964 million (2016)[1] |

| Agency executive |

|

| Website | National Institute of Standards and Technology |

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is a measurement standards laboratory, and a non-regulatory agency of the United States Department of Commerce. Its mission is to promote innovation and industrial competitiveness.

NIST's activities are organized into laboratory programs that include Nanoscale Science and Technology, Engineering, Information Technology, Neutron Research, Material Measurement, and Physical Measurement.

Following 9/11, NIST conducted the official investigation into the collapse of the World Trade Center buildings.

Constitution

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), known between 1901 and 1988 as the National Bureau of Standards (NBS), is a measurement standards laboratory, also known as a National Metrological Institute (NMI), which is a non-regulatory agency of the United States Department of Commerce. The institute's official mission is to:[3]

Promote U.S. innovation and industrial competitiveness by advancing measurement science, standards, and technology in ways that enhance economic security and improve our quality of life.— NIST

NIST had an operating budget for fiscal year 2007 (October 1, 2006-September 30, 2007) of about $843.3 million. NIST's 2009 budget was $992 million, and it also received $610 million as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act.[4] NIST employs about 2,900 scientists, engineers, technicians, and support and administrative personnel. About 1,800 NIST associates (guest researchers and engineers from American companies and foreign countries) complement the staff. In addition, NIST partners with 1,400 manufacturing specialists and staff at nearly 350 affiliated centers around the country. NIST publishes the Handbook 44 that provides the "Specifications, tolerances, and other technical requirements for weighing and measuring devices".

Initial mandate

The Articles of Confederation, ratified by the colonies in 1781, contained the clause, "The United States in Congress assembled shall also have the sole and exclusive right and power of regulating the alloy and value of coin struck by their own authority, or by that of the respective states—fixing the standards of weights and measures throughout the United States". Article 1, section 8, of the Constitution of the United States (1789), transferred this power to Congress; "The Congress shall have power...To coin money, regulate the value thereof, and of foreign coin, and fix the standard of weights and measures".

In January 1790 President George Washington, in his first annual message to Congress stated that, "Uniformity in the currency, weights, and measures of the United States is an object of great importance, and will, I am persuaded, be duly attended to", and ordered Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson to prepare a plan for Establishing Uniformity in the Coinage, Weights, and Measures of the United States, afterwards referred to as the Jefferson report. On October 25, 1791, Washington appealed a third time to Congress, "A uniformity of the weights and measures of the country is among the important objects submitted to you by the Constitution and if it can be derived from a standard at once invariable and universal, must be no less honorable to the public council than conducive to the public convenience", but it was not until 1838 that a uniform set of standards was worked out.

In 1821, John Quincy Adams had declared "Weights and measures may be ranked among the necessities of life to every individual of human society".[5]

History

From 1830 until 1901, the role of overseeing weights and measures was carried out by the Office of Standard Weights and Measures, which was part of the United States Department of the Treasury.[6] In 1901, in response to a bill proposed by Congressman James H. Southard (R, Ohio), the National Bureau of Standards was founded with the mandate to provide standard weights and measures, and to serve as the national physical laboratory for the United States. (Southard had previously sponsored a bill for metric conversion of the United States.) [7]

President Theodore Roosevelt appointed Samuel W. Stratton as the first director. The budget for the first year of operation was $40,000. The Bureau took custody of the copies of the kilogram and meter bars that were the standards for U.S. measures, and set up a program to provide metrology services for United States scientific and commercial users. A laboratory site was constructed in Washington, D.C., and instruments were acquired from the national physical laboratories of Europe. In addition to weights and measures, the Bureau developed instruments for electrical units and for measurement of light. In 1905 a meeting was called that would be the first "National Conference on Weights and Measures".

Initially conceived as purely a metrology agency, the Bureau of Standards was directed by Herbert Hoover to set up divisions to develop commercial standards for materials and products.[7]page 133 Some of these standards were for products intended for government use, but product standards also affected private-sector consumption. Quality standards were developed for products including some types of clothing, automobile brake systems and headlamps, antifreeze, and electrical safety. During World War I, the Bureau worked on multiple problems related to war production, even operating its own facility to produce optical glass when European supplies were cut off. Between the wars, Harry Diamond of the Bureau developed a blind approach radio aircraft landing system. During the Second World War, military research and development was carried out, including development of radio propagation forecast methods, the proximity fuze and the guided bomb.

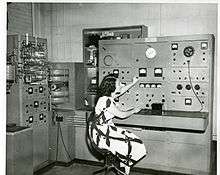

In 1948, financed by the Air Force, the Bureau began design and construction of SEAC, the Standards Eastern Automatic Computer. The computer went into operation in May 1950 using a combination of vacuum tubes and solid-state diode logic. About the same time the Standards Western Automatic Computer, was built at the Los Angeles office of the NBS and used for research there. A mobile version, DYSEAC, was built for the Signal Corps in 1954.

The "National Bureau of Standards" became the National Institute of Standards and Technology in 1988.[6]

Metric system

The Congress of 1866 legalized the use of the metric system through the passage of U.S. code 1952 Ed., Title 15, Ch 6, sections 204 and 205.[8] On May 20, 1875, 17 out of 20 countries signed a document known as the Metric Convention or the Treaty of the Meter, which established the International Bureau of Weights and Measures under the control of an international committee elected by the General Conference on Weights and Measures.[9]

Organization

NIST is headquartered in Gaithersburg, Maryland, and operates a facility in Boulder, Colorado. NIST's activities are organized into laboratory programs and extramural programs. Effective October 1, 2010, NIST was realigned by reducing the number of NIST laboratory units from ten to six.[10] NIST Laboratories include:[11]

- Center for Nanoscale Science and Technology (CNST)

- Communications Technology Laboratory (CTL)

- Engineering Laboratory (EL)

- Information Technology Laboratory (ITL)

- NIST Center for Neutron Research (NCNR)

- Material Measurement Laboratory (MML)

- Physical Measurement Laboratory (PML)

Extramural programs include:

- Hollings Manufacturing Extension Partnership (MEP), a nationwide network of centers to assist small and mid-sized manufacturers to create and retain jobs, improve efficiencies, and minimize waste through process improvements and to increase market penetration with innovation and growth strategies;

- Technology Innovation Program (TIP), a grant program where NIST and industry partners cost share the early-stage development of innovative but high-risk technologies;

- Baldrige Performance Excellence Program, which administers the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award, the nation's highest award for performance and business excellence.

NIST's Boulder laboratories are best known for NIST‑F1, which houses an atomic clock. NIST‑F1 serves as the source of the nation's official time. From its measurement of the natural resonance frequency of cesium—which defines the second—NIST broadcasts time signals via longwave radio station WWVB near Fort Collins, Colorado, and shortwave radio stations WWV and WWVH, located near Fort Collins and Kekaha, Hawaii, respectively.[12]

NIST also operates a neutron science user facility: the NIST Center for Neutron Research (NCNR). The NCNR provides scientists access to a variety of neutron scattering instruments, which they use in many research fields (materials science, fuel cells, biotechnology, etc.).

The SURF III Synchrotron Ultraviolet Radiation Facility is a source of synchrotron radiation, in continuous operation since 1961. SURF III now serves as the U.S. national standard for source-based radiometry throughout the generalized optical spectrum. All NASA-borne, extreme-ultraviolet observation instruments have been calibrated at SURF since the 1970s, and SURF is used for measurement and characterization of systems for extreme ultraviolet lithography.

The Center for Nanoscale Science and Technology (CNST) performs research in nanotechnology, both through internal research efforts and by running a user-accessible cleanroom nanomanufacturing facility. This "NanoFab" is equipped with tools for lithographic patterning and imaging (e.g., electron microscopes and atomic force microscopes).

Committees

NIST has seven standing committees:

- Technical Guidelines Development Committee (TGDC)

- Advisory Committee on Earthquake Hazards Reduction (ACEHR)

- National Construction Safety Team Advisory Committee (NCST Advisory Committee)

- Information Security and Privacy Advisory Board (ISPAB)

- Visiting Committee on Advanced Technology (VCAT)

- Baldrige National Quality Program Board of Overseers (BNQP Board of Overseers)

- Manufacturing Extension Partnership National Advisory Board (MEPNAB)

Projects

Measurements and standards

As part of its mission, NIST supplies industry, academia, government, and other users with over 1,300 Standard Reference Materials (SRMs). These artifacts are certified as having specific characteristics or component content, used as calibration standards for measuring equipment and procedures, quality control benchmarks for industrial processes, and experimental control samples.

Handbook 44

NIST publishes the Handbook 44 each year after the annual meeting of the National Conference on Weights and Measures (NCWM). Each edition is developed through cooperation of the Committee on Specifications and Tolerances of the NCWM and the Weights and Measures Division (WMD) of the NIST. The purpose of the book is a partial fulfillment of the statutory responsibility for "cooperation with the states in securing uniformity of weights and measures laws and methods of inspection".

NIST has been publishing various forms of what is now the Handbook 44 since 1918 and began publication under the current name in 1949. The 2010 edition conforms to the concept of the primary use of the SI (metric) measurements recommended by the Omnibus Foreign Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988.[13][14]

Homeland security

National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is currently developing government-wide identification card standards for federal employees and contractors to prevent unauthorized persons from gaining access to government buildings and computer systems.

World Trade Center Collapse Investigation

In 2002 the National Construction Safety Team Act mandated NIST to conduct an investigation into the collapse of the World Trade Center buildings 1 and 2 and the 47-story 7 World Trade Center. The "World Trade Center Collapse Investigation", directed by lead investigator Shyam Sunder,[15] covered three aspects, including a technical building and fire safety investigation to study the factors contributing to the probable cause of the collapses of the WTC Towers (WTC 1 and 2) and WTC 7. NIST also established a research and development program to provide the technical basis for improved building and fire codes, standards, and practices, and a dissemination and technical assistance program to engage leaders of the construction and building community in implementing proposed changes to practices, standards, and codes. NIST also is providing practical guidance and tools to better prepare facility owners, contractors, architects, engineers, emergency responders, and regulatory authorities to respond to future disasters. The investigation portion of the response plan was completed with the release of the final report on 7 World Trade Center on November 20, 2008. The final report on the WTC Towers—including 30 recommendations for improving building and occupant safety—was released on October 26, 2005.[16]

Election technology

NIST works in conjunction with the Technical Guidelines Development Committee of the Election Assistance Commission to develop the Voluntary Voting System Guidelines for voting machines and other election technology.

People

Four scientific researchers at NIST have been awarded Nobel Prizes for work in physics: William D. Phillips in 1997, Eric A. Cornell in 2001, John L. Hall in 2005 and David J. Wineland in 2012, which is the largest number for any U.S. government laboratory. All four were recognized for their work related to laser cooling of atoms, which is directly related to the development and advancement of the atomic clock. In 2011 Dan Shechtman was awarded the Nobel Prize in chemistry for his work on quasicrystals in the Metallurgy Division from 1982 to 1984. In addition, John Cahn was awarded the 2011 Kyoto Prize for Materials Science. Other notable people who have worked at NIST include:

- Milton Abramowitz

- James S. Albus

- Ferdinand Brickwedde

- Lyman James Briggs

- Edgar Buckingham

- John W. Cahn

- William Coblentz

- Ronald Colle

- Philip J. Davis

- Hugh L. Dryden

- Jack Edmonds

- Ugo Fano

- Charlotte Froese Fischer

- Tim Foecke

- John C. Garand

- Katharine Blodgett Gebbie

- Douglas Hartree

- Magnus Hestenes

- Russell A. Kirsch

- Cornelius Lanczos

- Wilfrid Mann

- William C. Martin

- William Meggers

- Christopher Monroe

- James G. Nell

- Frank W. J. Olver

- Ward Plummer

- Jacob Rabinow

- Richard Saykally

- Dan Shechtman

- Charlotte Moore Sitterly

- Irene Stegun

- Bill Stone

Directors

Since 1989, the director of NIST has been a Presidential appointee and is confirmed by the United States Senate,[17] and since that year the average tenure of NIST directors has fallen from 11 years to 2 years in duration. Since the 2011 reorganization of NIST, the director also holds the title of Undersecretary of Commerce for Technology. Fifteen individuals have officially held the position (in addition to three "acting" directors who served on a temporary basis ). They are:

- Samuel W. Stratton, 1901–1922

- George K. Burgess, 1923–1932

- Lyman J. Briggs, 1932–1945

- Edward U. Condon, 1945–1951

- Allen V. Astin, 1951–1969

- Lewis M. Branscomb, 1969–1972

- Richard W. Roberts, 1973–1975

- Ernest Ambler, 1975–1989

- John W. Lyons, 1990–1993

- Arati Prabhakar, 1993–1997

- Raymond G. Kammer, 1997–2000

- Karen Brown (acting), 2000–2001

- Arden L. Bement, Jr., 2001–2004

- Hratch Semerjian (acting), 2004–2005

- William Jeffrey, 2005–2007

- James Turner (acting), 2007–2008

- Patrick D. Gallagher, 2008–2014

- Willie E. May,[2] 2014–present

Controversy

The Guardian and the New York Times reported that NIST allowed the National Security Agency (NSA) to insert a cryptographically secure pseudorandom number generator called Dual EC DRBG into NIST standard SP 800-90 that had a backdoor that the NSA can use to covertly decrypt material that was encrypted using this pseudorandom number generator.[18] Both papers report[19][20] that the NSA worked covertly to get its own version of SP 800-90 approved for worldwide use in 2006. The leaked document states that "eventually, NSA became the sole editor". The reports confirm suspicions and technical grounds publicly raised by cryptographers in 2007 that the EC-DRBG could contain an kleptographic backdoor (perhaps placed in the standard by NSA).[21]

NIST responded to the allegations, stating that "NIST works to publish the strongest cryptographic standards possible" and that it uses "a transparent, public process to rigorously vet our recommended standards".[22] The agency stated that "there has been some confusion about the standards development process and the role of different organizations in it...The National Security Agency (NSA) participates in the NIST cryptography process because of its recognized expertise. NIST is also required by statute to consult with the NSA."[23] Recognizing the concerns expressed, the agency reopened the public comment period for the SP800-90 publications, promising that "if vulnerabilities are found in these or any other NIST standards, we will work with the cryptographic community to address them as quickly as possible”.[24]

Publications

The Journal of Research of the National Institute of Standards and Technology is the flagship scientific journal at NIST. It has been published since 1904.

See also

- AD-X2

- Advanced Encryption Standard process

- Inorganic Crystal Structure Database

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO)

- ISO/IEC 17025 - used by testing and calibration laboratories

- International System of Units, see International Bureau of Weights and Measures

- National Software Reference Library

- NIST hash function competition

- Smart Grid Interoperability Panel

- Technical Report Archive & Image Library for NIS-digitized series

- WWV (radio station)

References

- ↑ "2016 Appropriations Increase NIST Funding 166 percent". NIST. 2016. Retrieved 2016-01-13.

- 1 2 "Senate Confirms May as 15th NIST Director". NIST. 5 May 2015. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ↑ NIST General Information. Retrieved on August 21, 2010.

- ↑ "NIST Budget, Planning and Economic Studies". National Institute of Standards and Technology. October 5, 2010. Retrieved October 6, 2010.

- ↑ NBS special publication 447-Retrieved 2011-09-28

- 1 2 Records of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), National Archives and Records Administration website, (Record Group 167), 1830-1987.

- 1 2 John Perry, The Story of Standards, Funk and Wagnalls, 1953, Library of Congress Cat. No. 55-11094, p. 123

- ↑ NIST history page 41-Retrieved 2011-09-28

- ↑ International standards: page 22; -Retrieved 2011-09-28

- ↑ NIST Strengthens Laboratory Mission Focus with New Structure

- ↑ NIST Laboratories. National Institute of Standards and Technology. Retrieved on May 10, 2016.

- ↑ . NIST. Retrieved on March 18, 2014.

- ↑ Handbook 44- "Forward; page 5" Retrieved: 2011-09-28

- ↑ 100th Congress (1988) (Jun 16, 1988). "H.R. 4848". Legislation. GovTrack.us. Retrieved September 28, 2011.

Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988

- ↑ Eric Lipton (August 22, 2008). "Fire, Not Explosives, Felled 3rd Tower on 9/11, Report Says". New York Times.

- ↑ "Final Reports of the Federal Building and Fire Investigation of the World Trade Center Disaster". National Institute of Standards and Technology. October 2005.

- ↑ "2012 Plum Book". Government Printing Office. 2012. Retrieved 2016-12-02.

- ↑ Konkel, Frank (6 September 2013). "What NSA's influence on NIST standards means for feds". FCW. 1105 Government Information Group. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- ↑ James Borger; Glenn Greenwald (6 September 2013). "Revealed: how US and UK spy agencies defeat internet privacy and security". The Guardian. The Guardian. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- ↑ Nicole Perlroth (5 September 2013). "N.S.A. Able to Foil Basic Safeguards of Privacy on Web". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- ↑ Schneier, Bruce (15 November 2007). "Did NSA Put a Secret Backdoor in New Encryption Standard?". Wired. Condé Nast. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- ↑ Byers, Alex. "NSA encryption info could pose new security risk - NIST weighs in". Politico. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- ↑ Perlroth, Nicole. "Government Announces Steps to Restore Confidence on Encryption Standards". New York Times. Retrieved 11 September 2013.

- ↑ Office of the Director, NIST (10 September 2013). "Cryptographic Standards Statement". National Institute of Standsards in Technology. Retrieved 11 September 2013.

External links

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: National Institute of Standards and Technology |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to National Institute of Standards and Technology. |

- Main NIST website

- NIST in the Federal Register

- NIST Publications Portal

- The Official U.S. Time

- NIST Standard Reference Materials

- NIST Center for Nanoscale Science and Technology (CNST)

- NIST Scientific and Technical Data

- NIST Digital Library of Mathematical Functions

- Manufacturing Extension Partnership

- Historic technical reports from the National Bureau of Standards (and other Federal agencies) are available in the Technical Report Archive and Image Library (TRAIL)