Naïve realism (psychology)

- For the philosophy of perception, see naïve realism.

In social psychology, naïve realism is the human tendency to believe that we see the world around us objectively, and that people who disagree with us must be uninformed, irrational, or biased. Naïve realism provides a theoretical basis for several other cognitive biases, which are systematic errors in thinking and decision-making. These include the false consensus effect, actor-observer bias, bias blind spot, and fundamental attribution error, among others.

The term, as it is used in psychology today, was coined by social psychologist Lee Ross and his colleagues in the 1990s.[1][2] It is related to the philosophical concept of naïve realism, which is the idea that our senses allow us to perceive objects directly and without any intervening processes.[3] Social psychologists in the mid-20th century argued against this stance and proposed instead that perception is inherently subjective.[4]

Several prominent social psychologists have studied naïve realism experimentally, including Lee Ross, Andrew Ward, Dale Griffin, Emily Pronin, Thomas Gilovich, Robert Robinson, and Dacher Keltner. In 2010, the Handbook of Social Psychology recognized naïve realism as one of "four hard-won insights about human perception, thinking, motivation and behavior that ... represent important, indeed foundational, contributions of social psychology."[5]

Main assumptions

Lee Ross and fellow psychologist Andrew Ward have outlined three interrelated assumptions, or "tenets," that make up naïve realism. They argue that these assumptions are supported by a long line of thinking in social psychology, along with several empirical studies. According to their model, people:

- Believe that they see the world objectively and without bias.

- Expect that others will come to the same conclusions, so long as they are exposed to the same information and interpret it in a rational manner.

- Assume that others who do not share the same views must be ignorant, irrational, or biased.[1]

History of concept

Naïve realism follows from a subjectivist tradition in modern social psychology, which traces its roots back to one of the field's founders, a German-American psychologist named Kurt Lewin.[1][6] Lewin's ideas were strongly informed by Gestalt psychology, a 20th-century school of thought which focused on examining psychological phenomena in context, as parts of a whole.[7]

From the 1920s through the 1940s, Lewin developed an approach for studying human behavior which he called field theory.[8] Field theory proposes that a person's behavior is a function of the person and the environment.[9] Lewin considered a person's psychological environment, or "life space," to be subjective and thus distinct from physical reality.[4]

During this time period, subjectivist ideas also propagated throughout other areas of psychology. For example, Jean Piaget, a developmental psychologist, argued that children view the world through an egocentric lens, and they have trouble separating their own beliefs from the beliefs of others.[10]

In the 1940s and 1950s, early pioneers in social psychology applied the subjectivist view to the field of social perception. In 1948, psychologists David Kretch and Richard Krutchfield argued that people perceive and interpret the world according to their "own needs, own connotations, own personality, own previously formed cognitive patterns."[1][11][12]

Social psychologist Gustav Ichheiser expanded on this idea, noting how biases in person perception lead to misunderstandings in social relations. According to Ichheiser, "We tend to resolve our perplexity arising out of the experience that other people see the world differently than we see it ourselves by declaring that these others, in consequence of some basic intellectual and moral defect, are unable to see things 'as they really are' and to react to them 'in a normal way.' We thus imply, of course, that things are in fact as we see them, and that our ways are the normal ways."[13]

Solomon Asch, a prominent social psychologist who was also brought up in the Gestalt tradition, argued that people disagree because they base their judgments on different construals, or ways of looking at various issues.[6][14] However, they are under the illusion that their judgments about the social world are objective. "This attitude, which has been aptly described as naive realism, sees no problem in the fact of perception or knowledge of the surroundings. Things are what they appear to be; they have just the qualities that they reveal to sight and touch," he wrote in his textbook Social Psychology in 1952. "This attitude, does not, however, describe the actual conditions of our knowledge of the surroundings."[15]

Experimental evidence

"They Saw A Game"

In a seminal study in social psychology, which was published in a paper in 1954, students from Dartmouth and Princeton watched a video of a heated football game between the two schools.[16] Though they looked at the same footage, fans from both schools perceived the game very differently. The Princeton students "saw" the Dartmouth team make twice as many infractions as their own team, and they also saw the team make twice as many infractions compared to what the Dartmouth students saw. Dartmouth students viewed the game as being evenly-matched in violence, in which both sides were to blame. This study revealed that two groups perceived an event subjectively. Each team believed they saw the event objectively and that the other side's perception of the event was blinded by bias.[1]

False consensus effect

A 1977 study conducted by Ross and colleagues provided early evidence for a cognitive bias called the false consensus effect, which is the tendency for people to overestimate the extent to which others share the same views.[17] This bias has been cited as supporting the first two tenets of naïve realism.[1][5] In the study, students were asked whether they would wear a sandwich-board sign, which said "Eat At Joe's" on it, around campus. Then they were asked to indicate whether they thought other students were likely to wear the sign, and what they thought about students who were either willing to wear it or not. The researchers found that students who agreed to wear the sign thought that the majority of students would wear the sign, and they thought that refusing to wear the sign was more revealing of their peers' personal attributes. Conversely, students who declined to wear the sign thought that most other students would also refuse, and that accepting the invitation was more revealing of certain personality traits.

Hostile media effect

A phenomenon, referred to as the hostile media effect, demonstrates that partisans can view neutral events subjectively according to their own needs and values, and make the assumption that those who interpret the event differently are biased. For a study in 1985, pro-Israeli and pro-Arab students were asked to watch real news coverage on the 1982 Sabra and Shatila massacre, a massive killing of Palestinian refugees (Vallone, Lee Ross and Lepper, 1985).[5][18] Researchers found that partisans from both sides perceived the coverage as being biased in favor of the opposite viewpoint, and believed that the people in charge of the news program held the ideological views of the opposite side.

"Musical Tapping" study

More empirical evidence for naïve realism came from psychologist Elizabeth Newton's "musical tapping study" in 1990. For the study, participants were designed either as "tappers" or as "listeners." The tappers were told to tap out the rhythm of a well-known song, while the "listeners" were asked to try to identify the song. While tappers expected that listeners would guess the tune around 50 percent of the time, the listeners were able to identify it only around 2.5 percent of the time. This provided support for a failure in perspective-taking on the side of the tappers, and an overestimation of the extent to which others would share in "hearing" the song as it was tapped.[1]

Wall-Street Community Game

In 1993, Ross and Steven Samuels asked dorm resident advisors to nominate students to participate in a study, and to indicate whether those students were likely to cooperate or defect in the first round of the classic decision-making game called the Prisoner's Dilemma. The game was introduced to subjects in one of two ways: it was either referred to as the "Wall Street Game" or as the "Community Game." The researchers found that students in the "Community Game" condition were twice as likely to cooperate, and that it did not seem to make a difference whether students were previously categorized as "cooperators" versus "defectors." This experiment demonstrated that the game's label exerted more power on how the students played the game than the subjects' personality traits. Furthermore, the study showed that the dorm advisors did not make sufficient allowances for subjective interpretations of the game.[1]

Consequences

Naïve realism causes people to exaggerate differences between themselves and others. Psychologists believe that it can spark and exacerbate conflict, as well as create barriers to negotiation through several different mechanisms.[11]

Bias blind spot

One consequence of naïve realism is referred to as the bias blind spot, which is the ability to recognize cognitive and motivational biases in others while failing to recognize the impact of bias on the self. In a study conducted by Pronin, Lin, and Ross (2002), Stanford students completed a questionnaire about various biases in social judgment.[19] They indicated how susceptible they thought they were to these biases compared to the average student. The researchers found that the participants consistently believed that they were less likely to be biased than their peers. In a follow-up study, students answered questions about their personal attributes (e.g. how considerate they were) compared to those of other students. The majority of students saw themselves as falling above average on most traits, which provided support for a cognitive bias known as the better-than-average effect. Next, the students learned that 70 to 80 percent of people fall prey to this bias. When asked about the accuracy of their self-assessments, 63 percent of the students argued that their ratings had been objective, while 13 percent of students indicated they thought their ratings had been too modest.[20]

False polarization

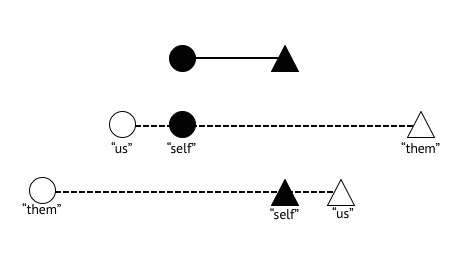

When an individual does not share our views, the third tenet of naïve realism attributes this discrepancy to three possibilities. The individual either has been exposed to a different set of information, is lazy or unable to come to a rational conclusion, or is under a distorting influence such as bias or self-interest.[1] This gives rise to a phenomenon called false polarization, which involves interpreting others' views as more extreme than they really are, and leads to a perception of greater intergroup differences (see Fig. 1).[6] People assume that they perceive the issue objectively, carefully considering it from multiple views, while the other side processes information in top-down fashion.[21] For instance, in a study conducted by Robinson et al. in 1996, pro-life and pro-choice partisans greatly overestimated the extremity of the views of the opposite side, and also overestimated the influence of ideology on others in their own group.[22]

Reactive devaluation

The assumption that others' views are more extreme than they are can create a barrier for conflict resolution. In a sidewalk survey conducted in the 1980s, pedestrians evaluated a nuclear arms' disarmament proposal (Stillinger et al., 1991).[23] One group of participants was told that the proposal was made by American President Ronald Reagan, while others thought the proposal came from Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev. The researchers found that 90 percent of the participants who thought the proposal was from Reagan supported it, while only 44 percent in the Gorbachev group indicated their support. This provided support for a phenomenon called reactive devaluation, which involves dismissing a concession from an adversary on the assumption that the concession is either motivated by self-interest or less valuable.[11]

See also

- List of cognitive biases

- Attribution theory

- Naïve cynicism

- Depressive realism

- Egocentric bias

- False-consensus effect

- Bias blind spot

- Curse of knowledge

- Hindsight bias

- Hostile media effect

- Attitude polarization

- Reactive devaluation

- Fundamental attribution error

- Empathy gap

- Confirmation bias

- Theory of mind

- False-belief task

- Spotlight effect

- Actor-observer bias

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Ross, L., & Ward, A. (1996). Naive realism in everyday life: Implications for social conflict and misunderstanding. In T. Brown, E. S. Reed & E. Turiel (Eds.), Values and Knowledge (pp. 103–135). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- ↑ Griffin, D., & Ross, L. (1991). Subjective construal, social inference, and human misunderstanding. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (pp. 319–359). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. doi:10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60333-0

- ↑ Nuttall, John (2002). An Introduction to Philosophy. Maiden, MA: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-7456-1663-6.

- 1 2 Hergenhahn, B. (2008). An Introduction to the History of Psychology. Cengage Learning. ISBN 0-495-50621-4.

- 1 2 3 Ross, L.; Lepper, M.; Ward, A., History of Social Psychology: Insights, Challenges, and Contributions to Theory and Application. In Fiske, S. T., In Gilbert, D. T., In Lindzey, G., & Jongsma, A. E. (2010). Handbook of Social Psychology. Vol.1. Hoboken, N.J: Wiley. doi:10.1002/9780470561119.socpsy001001

- 1 2 3 Robinson, Robert J.; Keltner, Dacher; Ward, Andrew; Ross, Lee (1995). "Actual versus assumed differences in construal: "Naive realism" in intergroup perception and conflict". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 68 (3): 404–417. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.68.3.404.

- ↑ Gestalt psychology. (2015). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved from http://www.britannica.com/science/Gestalt-psychology

- ↑ "Field Theory." International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences. 1968. Retrieved November 17, 2015 from Encyclopedia.com

- ↑ Lewin, Kurt (1939). "Field Theory and Experiment in Social Psychology: Concepts and Methods". American Journal of Sociology. 44 (6): 868–896. doi:10.1086/218177.

- ↑ Piaget, J. (1926) The Language and Thought of the Child. New York: Harcourt, Brace.

- 1 2 3 Molouki, S., & Pronin, E. (2015). Self and other. In E. Borgida & J. A. Bargh (Eds.), APA Handbook of Personality and Social Psychology, Volume 1: Attitudes and Social Cognition. Washington, DC: APA. doi:10.1037/14341-013

- ↑ Kretch, D.; Crutchfield, R.S. (1948). Theory and Problems of Social Psychology. New York: McGraw Hill. p. 94.

- ↑ Ichheiser, G. (1949) Misunderstandings in Human Relations: A study in false social perception. American Journal of Sociology, Supplement to the September issue, pp.1–72.

- ↑ Asch, S. E. (1940). "Studies in the Principles of Judgments and Attitudes: II. Determination of Judgments by Group and by Ego Standards". The Journal of Social Psychology. 12 (2): 433–465. doi:10.1080/00224545.1940.9921487.

- ↑ Asch, Solomon (1952). Social Psychology. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, Inc. pp. 46–47.

- ↑ Hastorf, Albert H.; Cantril, Hadley (1954). "They saw a game; a case study". The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 49 (1): 129–134. doi:10.1037/h0057880.

- ↑ Ross, Lee; Greene, David; House, Pamela (1977). "The "false consensus effect": An egocentric bias in social perception and attribution processes". Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 13 (3): 279–301. doi:10.1016/0022-1031(77)90049-x.

- ↑ Vallone, Robert P.; Ross, Lee; Lepper, Mark R. (1985). "The hostile media phenomenon: Biased perception and perceptions of media bias in coverage of the Beirut massacre". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 49 (3): 577–585. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.49.3.577. PMID 4045697.

- ↑ Pronin, Emily; Lin, Daniel Y.; Ross, Lee (2002). "The Bias Blind Spot: Perceptions of Bias in Self Versus Others". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 28 (3): 369–381. doi:10.1177/0146167202286008.

- ↑ Moskowitz, G.B. Social Cognition: Understanding Self and Others. NY, NY: The Guilford Press, 2005.

- ↑ Pronin, E., Puccio, C. T., & Ross, L. (2002). Understanding misunderstanding: Social psychological perspectives. In T. Gilovich, D. Griffin & D. Kahneman (Eds.), Heuristics and Biases: The Psychology of Intuitive Judgment. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511808098.038

- ↑ Jost, John T.; Major, Brenda (2001). The Psychology of Legitimacy: Emerging Perspectives on Ideology, Justice, and Intergroup Relations. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-78699-7.

- ↑ Ross, Lee (1995). "Reactive Devaluation in Negotiation and Conflict Resolution." In Kenneth Arrow, Robert Mnookin, Lee Ross, Amos Tversky, Robert B. Wilson (Eds.). Barriers to Conflict Resolution. New York: WW Norton & Co.

Further reading

- Ross, L., & Ward, A. (1995). Psychological barriers to dispute resolution. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. 27. , (pp. 255–304). San Diego, CA, US: Academic Press, ix, 317 pp. doi:10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60407-4

- Lilienfeld, Scott O. (2010) 50 Great Myths of Popular Psychology: Shattering Widespread Misconceptions About Human Behavior. Chichester, West Sussex; Wiley-Blackwell.

- Pronin, Emily; Gilovich, Thomas; Ross, Lee (2004-07-01). "Objectivity in the eye of the beholder: divergent perceptions of bias in self versus others"Psychological Review 111 (3): 781–799. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.111.3.781, ISSN 0033-295X. PMID 15250784.

- Liberman, V., et al. (2011) Naïve realism and capturing the "wisdom of dyads," Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2011.10.016

- Keltner, Dacher; Robinson, Robert J. (1993). "Imagined Ideological Differences in Conflict Escalation and Resolution". International Journal of Conflict Management. 4 (3): 249–262. doi:10.1108/eb022728.

- Liberman, Varda; Samuels, Steven M.; Ross, Lee (2004-09-01). "The Name of the Game: Predictive Power of Reputations versus Situational Labels in Determining Prisoner's Dilemma Game Moves". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 30 (9): 1175–1185. doi:10.1177/0146167204264004. ISSN 0146-1672. PMID 15359020.

- Ross, Lee (2014). "Barriers to agreement in the asymmetric Israeli–Palestinian conflict." Dynamics of Asymmetric Conflict, 7 (2–3): 120–136. doi:10.1080/17467586.2014.970565. ISSN 1746-7586.

- Ross, Lee; Nisbett, Richard E. (2011). The Person and the Situation: Perspectives of Social Psychology. Pinter & Martin Publishers. ISBN 978-1-905177-44-8.