National Malaria Eradication Program

In the United States, the National Malaria Eradication Program (NMEP) was launched on 1 July 1947. This federal program — with state and local participation — had succeeded in eradicating malaria in the United States by 1951.[1]

History

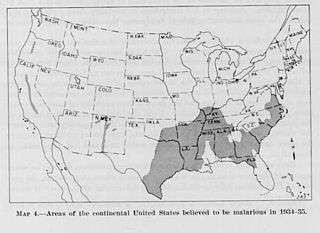

Prior to the establishment of the NMEP, malaria had been endemic across much of the United States. By the 1930s, it had become concentrated in 13 southeastern states. (For example, in the Tennessee River Valley it had a prevalence of about 30% in 1933.)

A national malaria eradication effort was originally proposed by Louis Laval Williams. The NMEP was directed by the federal Communicable Disease Center (now the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or CDC[2]) created in 1946 and based in Atlanta, Georgia. It was a cooperative undertaking by federal, state and local health agencies. The Program had evolved from the Office of Malaria Control in War Areas, which had been created in 1942 to suppress malaria near military bases in the United States during World War II. The CDC’s first director – Justin M. Andrews -- was also Georgia’s chief malariologist.

The new agency was a branch of the U.S. Public Health Service and Atlanta was chosen as its headquarters because malaria was locally endemic. Offices were located on the sixth floor of the Volunteer Building on Peachtree Street. With an annual budget of about $1 million, some 59% of its personnel were engaged in mosquito abatement and habitat control.[3] Among its 369 employees, the main jobs at CDC at this time were entomology and engineering. In 1946, there were only seven medical officers on duty and an early organization chart was drawn, somewhat fancifully, in the shape of a mosquito.[4]

During the CDC's first few years, more than 6,500,000 homes were sprayed with the insecticide DDT. DDT was applied to the interior surfaces of rural homes or entire premises in counties where malaria was reported to have been prevalent in recent years. In addition, wetland drainage, removal of mosquito breeding sites, and DDT spraying (occasionally from aircraft) were all pursued. In 1947, some 15,000 malaria cases were reported. By the end of 1949, over 4,650,000 housespray applications had been made and the United States was declared free of malaria as a significant public health problem. By 1950, only 2,000 cases were reported. By 1951, malaria was considered eliminated altogether from the country and the CDC gradually withdrew from active participation in the operational phases of the program, shifting its interest to surveillance. In 1952, CDC participation in eradication operations ceased altogether.

A major international effort along the lines of the NMEP — the Global Malaria Eradication Programme (1955–1969), administered by the World Health Organization — was unsuccessful.

References

Citations and notes

- ↑ Horton, Richard (2011), “Stopping Malaria: The Wrong Road”, The New York Review of Books, 24 February issue.

- ↑ The agency now called the CDC has had a welter of names over the years: Office of National Defense Malaria Control Activities (1942); Office of Malaria Control in War Areas (1942–1946); Communicable Disease Center (1946–1967); National Communicable Disease Center (1967–1970); Center for Disease Control (1970–1980); Centers for Disease Control (1980–1992) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1992 to present).

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, The History of Malaria, an Ancient Disease, Atlanta, GA, 2004.

- ↑ "Our History - Our Story". About CDC. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. April 26, 2013. Archived from the original on 19 June 2015.

Other sources

- Humphreys, Margaret (2001), Malaria: Poverty, Race, and Public Health in the United States, Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Daniel Sledge and George Mohler (2013), "Eliminating Malaria in the American South," American Journal of Public Health.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2010), “Elimination of Malaria in the United States (1947 — 1951)”.