Waitangi Day

| Waitangi Day | |

|---|---|

Traditional Maori Waitangi Day celebrations at Waitangi, Bay of Islands. | |

| Official name | Waitangi Day |

| Observed by | New Zealanders |

| Type | Nationwide |

| Observances | Family meetings, hui, parades, citizenship ceremonies, Order of New Zealand honours. |

| Date | 6 February |

| Next time | 6 February 2017 |

| Frequency | annual |

Waitangi Day (named after Waitangi, where the Treaty of Waitangi was first signed) commemorates a significant day in the history of New Zealand. It is observed as a public holiday each year on 6 February to celebrate the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, New Zealand's founding document, on that date in 1840. In recent legislation, if 6 February falls on a Saturday or Sunday, the Monday that immediately follows becomes a public holiday.[1]

History

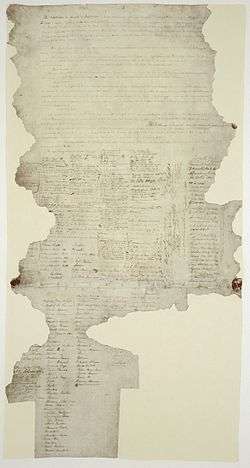

The Treaty of Waitangi was first signed on 6 February 1840, in a marquee in the grounds of James Busby's house (now known as the Treaty house) at Waitangi in the Bay of Islands by representatives acting on behalf of the British Crown and initially, more than 40 Māori chiefs. During the next seven months, copies of the treaty were carried around the country to give other chiefs the opportunity to sign.[2] The Treaty made New Zealand a part of the British Empire, guaranteed Māori rights to their land and gave Māori the rights of British subjects. There are differences between the English version and the Māori translation of the Treaty, and since 1840 this has led to debate over exactly what was agreed to at Waitangi. Māori have generally seen the Treaty as a sacred pact, while for many years Pākehā (the Māori word for New Zealanders of predominantly European ancestry) ignored it. By the early twentieth century, however, some Pākehā were beginning to see the Treaty as their nation's founding document and a symbol of British humanitarianism. Unlike Māori, Pākehā have generally not seen the Treaty as a document with binding power over the country and its inhabitants. In 1877 Chief Justice James Prendergast declared it to be a 'legal nullity', a position it held until the Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975, when it regained significant legal standing.

Early celebrations

Prior to 1934, most celebrations of New Zealand's founding as a colony were held on 29 January, the date on which William Hobson arrived in the Bay of Islands to issue the British proclamation of sovereignty. The proclamation had been prepared by colonial office officials in England. Hobson had no draft treaty. From the British perspective the proclamation was the key legal document, "what the treaty said was less important".[3] In 1932, Governor-General Lord Bledisloe and his wife purchased and presented to the nation the run-down house of James Busby, where the treaty was initially signed. The Treaty house and grounds were made a public reserve, which was dedicated on 6 February 1934. This event is considered by some to be the first Waitangi Day, although celebrations were not yet held annually. At the time, it was the most representative meeting of Māori ever held. Attendees included the Māori King Korokī Mahuta and thousands of Pākehā. Some Māori may have also been commemorating the 100th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence of New Zealand, but there is little evidence of this.

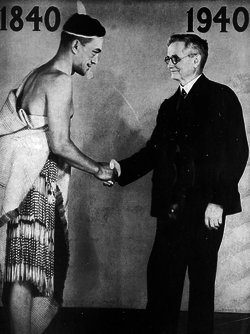

In 1940, another major event was held at the grounds, commemorating the 100th anniversary of the treaty signing. This was less well attended, partially because of the outbreak of World War II and partially because the government had recently offended the Māori King. However the event was still a success and helped raise the profile of the treaty.

Annual commemorations

Annual commemorations of the treaty signing began in 1947. The 1947 event was a Royal New Zealand Navy ceremony centring on a flagpole which the Navy had paid to erect in the grounds. The ceremony was brief and featured no Māori. The following year, a Māori speaker was added to the line-up, and subsequent additions to the ceremony were made nearly every year. From 1952, the Governor General attended, and from 1958 the Prime Minister also attended, although not every year. From the mid-1950s, a Māori cultural performance was usually given as part of the ceremony. Many of these early features remain a part of Waitangi Day ceremonies, including a naval salute, the Māori cultural performance (now usually a ceremonial welcome), and speeches from a range of Māori and Pākehā dignitaries.

Public holiday

Waitangi Day was proposed as a public holiday by the New Zealand Labour Party in their 1957 party manifesto. After Labour won the election they were reluctant to create a new public holiday, so the Waitangi Day Act was passed in 1960 making it possible for a locality to substitute Waitangi Day as an alternative to an existing public holiday. In 1963, after a change in government, Waitangi Day was substituted for Auckland Anniversary Day as the provincial holiday in Northland.

Waitangi Day underwent 'Mondayisation' in legislation enacted in 2013, shifting the public holiday to Monday if it falls on the weekend.[1]

New Zealand Day

In 1971 the Labour shadow minister of Māori Affairs, Matiu Rata, introduced a private member's bill to make Waitangi Day a national holiday, to be called New Zealand Day. This was not passed into law. After the 1972 election of the third Labour government under Norman Kirk, it was announced that from 1974 Waitangi Day would be a national holiday known as New Zealand Day. The New Zealand Day Act 1973 was passed in 1973.

For Norman Kirk, the change was simply an acceptance that New Zealand was ready to move towards a broader concept of nationhood. Diplomatic posts had for some years marked the day, and it seemed timely in view of the country's increasing role on the international stage that the national day be known as New Zealand Day. At the 1974 celebrations, the Flag of New Zealand was flown for the first time at the top of the flagstaff at Waitangi, rather than the Union Flag, and a replica of the flag of the United Tribes of New Zealand was also flown.

The election of the third National government in 1975 led to the day being renamed Waitangi Day because the new Prime Minister, Rob Muldoon, did not like the name "New Zealand Day" and many Māori felt the new name debased the Treaty of Waitangi.[4] Another Waitangi Day Act was passed in 1976 to change the name of the day back to Waitangi Day.

Controversy and protest

Although this is New Zealand's national day, the commemoration has normally been the focus of protest by Māori activists and other activists and is often marred by controversy. There has been opposition to the Treaty as far back as the first meeting at Waitangi on February 4, 1840; with a number of chiefs such as Moka Te Kainga-mataa, Rewa and Te Kemara challenging the Crown's right to rule. One of these was Ngapuhi (Patukeha) chief, Moka Te Kainga-mataa, who specifically referred to the terms and conditions of the Treaty, focussing on the authority that the Crown would have in relation to land transactions. Moka forced Hobson to reiterate what he had proclaimed a week earlier at the Christ Church on January 30, 1840, and by doing this, he was attempting to test Hobson's word, to put any of his doubts to rest. As a result of the discussion, Moka refused point-blank to sign the Treaty, despite two of his brothers and the majority of his peers having done so on February 6, 1840. Rewa was a reluctant signatory and quickly decided that he would not support the Treaty; travelling as far as Opotiki with his brother Moka, in order to persuade other chiefs not to sign - thus Moka could be viewed as being the first Maori activist. Fast forward to 1971, and Waitangi and Waitangi Day had become a focus of protest concerning treaty injustices, with Nga Tamatoa leading early protests. Activists initially called for greater recognition of the Treaty, but by the early 1980s, protest groups were also arguing that the treaty was a fraud with which Pākehā had conned Māori out of their land. Attempts were made by groups including the Waitangi Action Committee to halt the celebrations.[5] This led to major confrontations between police and protesters, sometimes resulting in dozens of arrests. When the treaty gained greater official recognition in the mid-1980s, emphasis switched back to calls to honour the treaty, and protesters generally returned to the aim of raising awareness of the treaty and what they saw as its neglect by the state.

Some New Zealand politicians and commentators, such as Paul Holmes, have felt that Waitangi Day is too controversial to be a national day and have sought to replace it with Anzac Day.[6] Others, for example the United Future Party's Peter Dunne, have suggested that the name of the day be changed back to New Zealand Day.[7]

Recent protests

Several hundred protesters often gather at Waitangi to reflect the long-standing frustrations Māori have fostered since the Treaty's signing. Although not part of the Government celebrations, Māori sovereignty activists often fly the Tino Rangatiratanga flag from the flagstaff. Attempts at vandalism of the flagstaff are often an objective of these protests, carrying on a tradition that dates from the 19th century when Hone Heke chopped down the British flagstaff in nearby Russell. In 2004, protesters succeeded in flying the Tino Rangatiratanga flag above the other flags on the flagstaff by flying it from the top of a nearby tree. Some commentators described this gesture as audacious and bold.

| Wikinews has related news: |

Because of the level of protest and threats that had previously occurred at Waitangi, the previous Prime Minister Helen Clark did not attend in 2000. The official celebrations were shifted from Waitangi to Wellington in 2001. Some Māori felt that this was an insult to them and to the Treaty. In 2003 and 2004, the anniversary was again officially commemorated at the Treaty house at Waitangi. In 2004 Leader of the Opposition Don Brash was hit with mud as he entered the marae.[8]

On 5 February 2009, the day before Waitangi Day, as current Prime Minister John Key was being escorted onto a marae, he was challenged by Wikitana and John Junior Popata, nephews of then Māori Party MP Hone Harawira.[9] Both admitted to assault and were sentenced to 100 hours of community service.[10] In 2011 Wikitana and John again heckled Key as he entered the marae.[11] A wet T-shirt thrown at Queen Elizabeth II[12] and other attacks on various Prime Ministers at Waitangi on 6 February have resulted in a large police presence as well as the large contingent of the armed forces. In 2016 a nurse protesting against the signing of a trade agreement threw a rubber dildo at Steven Joyce, the MP representing the Prime Minister, who had refused to attend, having been denied normal speaking rights. The woman was arrested but later released.[13]

Celebrations

At Waitangi

Celebrations at Waitangi often commence the previous day, 5 February, at the Ngapuhi Te Tii marae, where political dignitaries are welcomed onto the marae and hear speeches from the local iwi. These speeches often deal with the issues of the day, and vigorous and robust debate occurs.

At dawn on Waitangi Day, the Royal New Zealand Navy raises the New Zealand Flag, Union Flag and White Ensign on the flagstaff in the treaty grounds. The ceremonies during the day generally include a church service and cultural displays such as dance and song. Several waka and a navy ship also re-enact the calling ashore of Governor Hobson to sign the treaty. The day closes with the flags being lowered by the Navy in a traditional ceremony.

Elsewhere in New Zealand

In recent years, communities throughout New Zealand have been celebrating Waitangi Day in a variety of ways. These often take the form of public concerts and festivals. Some marae use the day as an open day and an educational experience for their local communities, giving them the opportunity to experience Māori culture and protocol. Other marae use the day as an opportunity to explain where they see Māori are and the way forward for Māori in New Zealand. Another popular way of celebrating the day is at concerts held around the country. Since the day is also Bob Marley's birthday, reggae music is especially popular. Wellington has a long running "One Love" festival that celebrates peace and unity. Another such event is "Groove in the Park", held in the Auckland Domain before 2007 and at Western Springs subsequently. Celebrations are largely muted in comparison to those seen on the national days of most countries. There are no mass parades, nor truly widespread celebrations. As the day is a public holiday, and coincides with the warmest part of the New Zealand summer, many people take the opportunity to spend the day at the beach – an important part of New Zealand culture.

Elsewhere in the world

In London, UK, which has one of the largest New Zealand expatriate populations, the occasion is celebrated by the Waitangi Day Ball, held by the New Zealand Society UK. The focus of the event is a celebration of New Zealand's unity and diversity as a nation. The Ball also hosts the annual UK New Zealander of the Year awards, cultural entertainment from London-based Māori group Ngāti Rānana and fine wine and cuisine from New Zealand. A service is also held by the society at the church of St Lawrence Jewry.[14]

Another tradition has arisen in recent years to celebrate Waitangi Day. On the closest Saturday to 6 February, Kiwis participate in a pub crawl using the London Underground's Circle Line.[15] Although the stated aim is to consume one drink at each of the 27 stops, most participants stop at a handful of stations, usually beginning at Paddington and moving anti-clockwise towards Temple. At 4 pm, a large-scale haka is performed at Parliament Square as Big Ben marks the hour. Participants wear costumes and sing songs such as "God Defend New Zealand", all of which is in stark contrast to the much more subdued observance of the day in New Zealand itself.

In many other countries with a New Zealand expatriate population, Waitangi Day is celebrated privately. The day is officially celebrated by all New Zealand embassies and High Commissions.

For Waitangi Day 2007, Air New Zealand commissioned a number of New Zealanders living in Los Angeles and Southern California to create a sand sculpture of a silver fern on the Santa Monica Beach creating a stir in the surrounding area.[16]

At the Kingston Butter Factory in Kingston, Queensland, Australia, Te Korowai Aroha (Cloak of Love) Association[17] have been holding Waitangi Day Celebrations since 2002, with an excess of 10,000 expats, Logan City Council representatives and Indigenous Australians coming together to commemorate in a peaceful alcohol- and drug-free occasion.

On the Gold Coast, in Australia, where there is a large New Zealand expatriate population, Waitangi Day is celebrated by around 10,000 people at Carrara Stadium. It is called the "Waitangi Day and Pacific Islands Festival". It not only embraces Waitangi day, but Pacific Islander culture. In 2009, iconic Kiwi bands Herbs and Ardijah featured, as well as local singers and performers. up to 5,000 people.

Waitangi Day is both commemorated and celebrated by upwards of 5,000 Kiwis resident in Sydney. Major 'Waitangi Day' celebrations have been happening on the closest weekend to the day, for many years and have grown from strength to strength, with the most attended Waitangi event being held at Holroyd Gardens, Merrylands. This day sees cultural performances, bands, a myriad of food stalls and 'hangi' for those missing New Zealand. February 6, 2015, saw the inaugural 'Waitangi Day Commemoration' held at Nurragingy Reserve on Friday 6 February 2015, where the focus is more on the document itself, the Treaty process and the significance to Maori and Kiwi today. It was co-hosted by the Blacktown City Council and the New South Wales Maori Wardens.

See also

References

- 1 2 "Extra public holidays voted in". 3 News NZ. 17 April 2013.

- ↑ "Creating the Treaty of Waitangi". Te Ara - The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- ↑ Before Hobson.pp 159-260 T. Simpson. Blythswood Press.2015.

- ↑ Waitangi Day at NZhistory.net.nz

- ↑ Hazlehurst, Kayleen M. (1995), ‘Ethnicity, Ideology and Social Drama: The Waitangi Day Incident 1981’ in Alisdair Rogers and Steven Vertovec, eds, The Urban Context: Ethnicity, Social Networks and Situational Analysis, Oxford and Washington D.C., p.83; Walker, Ranginui (1990), Ka Whawhai Tonu Matou: Struggle without End, Auckland, p.221.

- ↑ Paul Holmes (11 February 2012). "Waitangi Day a complete waste". New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ↑ "United Future press release". UnitedFuture. 5 February 2007.

- ↑ "Mud thrown at Brash at marae". The New Zealand Herald. 5 February 2004. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- ↑ Trevett, Claire (6 February 2009). "Elders condemn attack on PM". The New Zealand Herald.

- ↑ "Brothers sentenced for assaulting John Key". The New Zealand Herald. NZPA. 12 June 2009. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- ↑ Yvonne Tahana & Claire Trevett (5 February 2011). "Harawira proud of nephew's protest". The New Zealand Herald. with NZPA. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- ↑ David V. James; Paul E. Mullen; Michele T. Pathé; J. Reid Meloy; Frank R. Farnham; Lulu Preston & Brian Darnley (2008). "Attacks on the British Royal Family: The Role of Psychotic Illness" (PDF). J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 36: 59–67.

- ↑ TVNZ. One News. 5 Feb 2016.

- ↑ "St Lawrence Jewry February 2016 Newsletter" (PDF). Company of Distillers. February 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ↑ Ben, Machell (13 February 2006) "And another thing... Boozing with Maoris and inflatable sheep". The Times, Retrieved 13 June 2011

- ↑ YouTube.com, Waitangi Day in Los Angeles

- ↑ WhereIlive.com.au, Kiwi occasion fun for all

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Waitangi Day. |

- A history of Waitangi Day at NZHistory.net.nz

- WaitaingiTribunal.govt.nz, Introducing the Treaty.