Nine Men's Morris

|

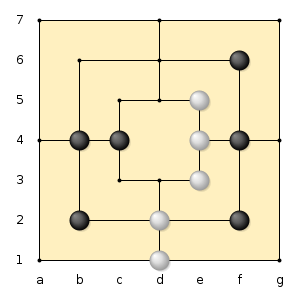

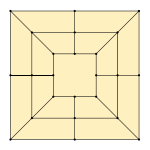

A game of Nine Men's Morris in phase two. Even if it is Black's turn, White can remove a black piece each time a mill is formed by moving e3-d3 and then back again d3-e3. | |

| Years active | > 2000 years ago to present |

|---|---|

| Genre(s) |

Board game Abstract strategy game |

| Players | 2 |

| Age range | Any |

| Setup time | < 1 minute |

| Playing time | 5–60 minutes |

| Random chance | None |

| Skill(s) required | Strategy, tactics |

| Synonym(s) |

Nine Man Morris Mill, Mills, or The Mill Game Merels or Merrills Merelles, Marelles, or Morelles Ninepenny Marl Cowboy Checkers |

Nine Men's Morris is a strategy board game for two players dating at least to the Roman Empire.[1] The game is also known as Nine Man Morris, Mill, Mills, The Mill Game, Merels, Merrills, Merelles, Marelles, Morelles and Ninepenny Marl[2] in English. The game has also been called Cowboy Checkers and is sometimes printed on the back of checkerboards. Nine Men's Morris is a solved game in which either player can force the game into a draw.[3]

Three main variants of Nine Men's Morris are Three-, Six- and Twelve-Men's Morris.

Rules

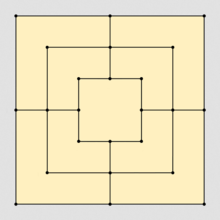

The board consists of a grid with twenty-four intersections or points. Each player has nine pieces, or "men", usually coloured black and white. Players try to form 'mills'—three of their own men lined horizontally or vertically—allowing a player to remove an opponent's man from the game. A player wins by reducing the opponent to two pieces (where he could no longer form mills and thus be unable to win), or by leaving him without a legal move.

The game proceeds in three phases:

- Placing men on vacant points

- Moving men to adjacent points

- (optional phase) Moving men to any vacant point when the player has been reduced to three men

Phase 1: Placing pieces

The game begins with an empty board. The players determine who plays first, then take turns placing their men one per play on empty points. If a player is able to place three of his pieces on contiguous points in a straight line, vertically or horizontally, he has formed a mill and may remove one of his opponent's pieces from the board and the game. Any piece can be chosen for the removal, but a piece not in an opponent's mill must be selected, if possible. After all men have been placed, phase two begins.

Phase 2: Moving pieces

Players continue to alternate moves, this time moving a man to an adjacent point. A piece may not "jump" another piece. Players continue to try to form mills and remove their opponent's pieces as in phase one. A player can "break" a mill by moving one of his pieces out of an existing mill, then moving it back to form the same mill a second time (or any number of times), each time removing one of his opponent's men. The act of removing an opponent's man is sometimes called "pounding" the opponent. When one player has been reduced to three men, phase three begins.

Phase 3: "Flying"

When a player is reduced to three pieces, there is no longer a limitation on that player of moving to only adjacent points: The player's men may "fly" (or "hop",[4][5] or "jump"[6]) from any point to any vacant point.

Some rules sources say this is the way the game is played,[5][6] some treat it as a variation,[4][7][8][9] and some don't mention it at all.[10] A 19th-century games manual calls this the "truly rustic mode of playing the game".[4] Flying was introduced to compensate when the weaker side is one man away from losing the game.

Strategy

At the beginning of the game, it is more important to place pieces in versatile locations rather than to try to form mills immediately and make the mistake of concentrating one's pieces in one area of the board.[11] An ideal position, which typically results in a win, allows a player to shuttle one piece back and forth between two mills, removing a piece every turn.

Variants

Three Men's Morris

Three Men's Morris, also called "Nine Holes", is played on the points of a grid of 2×2 squares, or in the squares of a grid of 3×3 squares as in tic-tac-toe. The game is for two players; each player has three men. The players put one man on the board in each of their first three plays, winning if a mill is formed (as in tic-tac-toe). After that, each player moves one of his men, according to one of the following rules versions:

- To any empty position

- To any adjacent empty position

A player wins by forming a mill.[12]

H. J. R. Murray calls version No. 1 "Nine Holes", and version No. 2 "Three Men's Morris" or "The Smaller Merels".

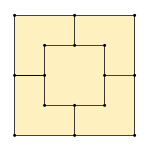

Six Men's Morris

Six Men's Morris gives each player six pieces and is played without the outer square of the board for Nine Men's Morris. Flying is not permitted.[13] The game was popular in Italy, France and England during the Middle Ages but was obsolete by 1600.[13]

This board is also used for Five Men's Morris (also called "Smaller Merels"). Seven Men's Morris uses this board with a cross in the center.

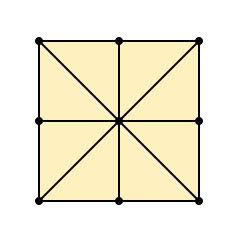

Twelve Men's Morris

Twelve Men's Morris adds four diagonal lines to the board and gives each player twelve pieces. This means the board can be filled in the placement stage; if this happens the game is a draw. This variation on the game is popular amongst rural youth in South Africa where it is known as Morabaraba and is now recognized as a sport in that country. H. J. R. Murray also calls the game "the larger merels".

This board is also used for Eleven Men's Morris.

Lasker Morris

This variant (also called Ten Men's Morris) was invented by Emanuel Lasker, chess world champion from 1894 to 1921. It is based on the rules of Nine Men’s Morris, but there are two differences: 1) Each player gets ten pieces; 2) Pieces can be moved in the first phase already. This means each player can choose to either place a new piece or to move one of his pieces already on the board. This variant is more complex than Nine Men's Morris and draws are less likely.[14]

History

According to R. C. Bell, the earliest known board for the game includes diagonal lines and was "cut into the roofing slabs of the temple at Kurna in Egypt" c. 1400 BCE.[13] However, Friedrich Berger writes that some of the diagrams at Kurna include Coptic crosses, making it "doubtful" that the diagrams date to 1400 BCE. Berger concludes, "certainly they cannot be dated."[1]

One of the earliest mentions of the game may be in Ovid's Ars Amatoria.[1][13] In book III (c. 8 CE), after discussing Latrones, a popular board game, Ovid wrote:

There is another game divided into as many parts as there are months in the year. A table has three pieces on either side; the winner must get all the pieces in a straight line. It is a bad thing for a woman not to know how to play, for love often comes into being during play.

Berger believes the game was "probably well known by the Romans", as there are many boards on Roman buildings, even though dating them is impossible because the buildings "have been easily accessible" since they were built. It is possible that the Romans were introduced to the game via trade routes, but this cannot be proven.[1]

_-_stol_za_mlin_i_%C5%A1ah.jpg)

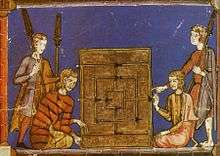

The game peaked in popularity in medieval England.[4] Boards have been found carved into the cloister seats at the English cathedrals at Canterbury, Gloucester, Norwich, Salisbury and Westminster Abbey.[13] These boards used holes, not lines, to represent the nine spaces on the board—hence the name "nine holes"—and forming a diagonal row did not win the game.[15] Another board is carved into the base of a pillar in Chester Cathedral in Chester.[16] Giant outdoor boards were sometimes cut into village greens. In Shakespeare's 17th century work A Midsummer Night's Dream, Titania refers to such a board: "The nine men's morris is filled up with mud" (A Midsummer Night's Dream, Act II, Scene I).

Some authors say the game's origin is uncertain.[4] It has been speculated that its name may be related to Morris dances, and hence to Moorish, but according to Daniel King, "the word 'morris' has nothing to do with the old English dance of the same name. It comes from the Latin word merellus, which means a counter or gaming piece."[10] King also notes that the game was popular among Roman soldiers.

In some European countries, the design of the board was given special significance as a symbol of protection from evil,[1] and "to the ancient Celts, the Morris Square was sacred: at the center lay the holy Mill or Cauldron, a symbol of regeneration; and emanating out from it, the four cardinal directions, the four elements and the four winds."[4]

Related games

- Achi, from Ghana, is played on a Three Men's Morris board with diagonals. Each player has four pieces, which can only move to adjacent spaces.[17]

- Kensington is a similar game in which two players take turns placing pieces and try to arrange them in certain ways.

- Luk Tsut K'i ("Six Man Chess") in Canton and Tapatan in the Philippines are equivalent to Three Men's Morris played on a board with diagonals.[18]

- Morabaraba, almost equivalent to Twelve Men's Morris. However, rather than men, the counters are called "cows." It is played competitively internationally in competitions run by the International Wargames Federation.

- Shax is played on the board of Nine Men's Morris, but with somewhat different rules and with twelve pieces per player instead of nine.

- Fangqi is played on a seven-by-seven grid. Players move pieces one point at a time along the grid, attempting to form four-by-four squares and removing one of the opponent's pieces after forming a square. It is played in northwest China and Xinjiang.

- Tic-tac-toe uses a three-by-three board, on which players place pieces (or make marks) in turn until one player wins by forming an orthogonal or diagonal line or until the board is full and the game is drawn.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Berger, Friedrich (2004). "From circle and square to the image of the world: a possible interpretation for some petroglyphs of merels boards" (PDF). Rock Art Research. 21 (1): 11–25. Retrieved 2007-01-12.

- ↑ Hone, William (1826). The Every-Day Book. London: Hunt and Clarke. ASIN B0010SXPN0.

- ↑ Gasser, Ralph (1996). "Solving Nine Men's Morris" (PDF). Games of No Chance. 29: 101–113. Retrieved 2015-06-01.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mohr, Merilyn Simonds (1997). The New Games Treasury. Houghton Mifflin. pp. 30–32. ISBN 1-57630-058-7.

- 1 2 Wood, Clement; Gloria Goddard (1940). The Complete Book of Games. Garden City, New York: Garden City Books. pp. 342–43.

- 1 2 Foster, R. F. (1946). Foster's Complete Hoyle: An Encyclopedia of Games. J. B. Lippincott Company. pp. 568–69.

- ↑ Ainslie, Tom (2003). Ainslie's Complete Hoyle. Barnes & Noble Books. pp. 404–06. ISBN 0-7607-4159-X.

- ↑ Morehead, Albert H.; Richard L. Frey; Geoffrey Mott-Smith (1956). The New Complete Hoyle. Garden City, New York: Garden City Books. pp. 647–649.

- ↑ Grunfeld, Frederic V. (1975). Games of the World. Holt, Rinehart and Winston. pp. 59–61. ISBN 0-03-015261-5.

- 1 2 King, Daniel (2003). Games. Kingfisher plc. pp. 10–11. ISBN 0-7534-0816-3.

- ↑ Vedar, Erwin A.; Wei Tu; Elmer Lee. "Nine Men's Morris". GamesCrafters. University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2006-12-31.

- ↑ Murray, H. J. R. (1913). A History of Chess (Reissued ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 614. ISBN 0-19-827403-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bell, R. C. (1979). Board and Table Games from Many Civilizations, volume 1. New York City: Dover Publications. pp. 90–92. ISBN 0-486-23855-5.

- ↑ http://www.althofer.de/stahlhacke-lasker-morris-2003.pdf

- ↑ "Nine Holes". Row Games. Elliott Avedon Museum and Archive of Games. 2005-09-12. Retrieved 2007-01-09.

- ↑ Hickey, Julia (2005). "The Hidden Treasures of Chester Cathedral". TimeTravel-Britain.com. Retrieved 2007-01-13.

- ↑ Bell, R. C. (1979). Board and Table Games from Many Civilizations, volume 2. New York City: Dover Publications. pp. 55–56. ISBN 0-486-23855-5.

- ↑ Culin, Stewart (October–December 1900). "Philippine Games". American Anthropologist, New Series (PDF). 2 (4): 643–656. doi:10.1525/aa.1900.2.4.02a00040. JSTOR 659313.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Morris games. |

- "What Planet is This?" by Sean B. Palmer

- Nine Men's Morris at BoardGameGeek

Variants

- Three Men's Morris at BoardGameGeek

- Six Men's Morris at BoardGameGeek

- Twelve Men's Morris at BoardGameGeek