Noor Inayat Khan

| Noor Inayat Khan GC Croix de guerre | |

|---|---|

Noor-un-Nisa Inayat Khan c.1943 | |

| Nickname(s) |

"Madeleine" (Callsign: Nurse) "Jeanne-Marie Renier" "Nora Baker" |

| Born |

2 January 1914 St. Petersburg, Russian Empire |

| Died |

13 September 1944 (aged 30) Dachau concentration camp, Germany |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch | Women's Auxiliary Air Force |

| Years of service | 1940–1944 |

| Rank | Assistant Section Officer |

| Unit |

Special Operations Executive Cinema |

| Battles/wars | Second World War |

| Awards |

Mentioned in dispatches |

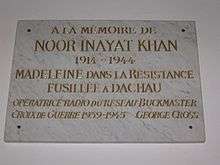

Noor-un-Nisa Inayat Khan GC (Hindustani/Urdu): نور عنایت خان, Devanagari: नूर इनायत ख़ान) (2 January 1914 – 13 September 1944) was an Allied Special Operations Executive (SOE) agent during the Second World War who was posthumously awarded the George Cross, the highest civilian decoration in the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth nations. Also known as "Nora Baker",[1] "Madeleine",[2] and "Jeanne-Marie Rennier", she was of Indian and American origin. As an SOE agent, she became the first female radio operator to be sent from Britain into occupied France to aid the French Resistance.

Early years

Inayat Khan,[2] the eldest of four children, was born on 2 January 1914 in St. Petersburg, Russia. Her siblings were Vilayat (1916–2004), Hidayat (1917–2016), and Khair-un-Nisa (1919–2011).[3] Her father, Hazrat Inayat Khan, came from a noble Indian Muslim family[3]—his mother was a descendant of the uncle of Tipu Sultan, the 18th-century ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore. He lived in Europe as a musician and a teacher of Sufism. Her mother, Pirani Ameena Begum (born Ora Ray Baker), was an American[2][3] from Albuquerque, New Mexico, who met Hazrat Inayat Khan during his travels in the United States. Ora Baker was the half-sister of American yogi and scholar Pierre Bernard, her guardian at the time she met Inayat (Hazrat is an honorific, translated as Saint).[4] Vilayat later became head of the Sufi Order International.

In 1914, shortly before the outbreak of the First World War, the family left Russia for London, and lived in Bloomsbury. Inayat Khan attended nursery at Notting Hill. In 1920 they moved to France, settling in Suresnes near Paris, in a house that was a gift from a benefactor of the Sufi movement. After the death of her father in 1927, Inayat Khan took on the responsibility for her grief-stricken mother and her younger siblings. As a young girl, she was described as quiet, shy, sensitive, and dreamy. She studied child psychology at the Sorbonne and music at the Paris Conservatory under Nadia Boulanger, composing for harp and piano. She began a career writing poetry and children's stories, and became a regular contributor to children's magazines and French radio. In 1939 her book, Twenty Jataka Tales,[5] inspired by the Jataka tales of Buddhist tradition, was published in London.[6]

After the outbreak of the Second World War, when France was overrun by German troops, the family fled to Bordeaux and, from there by sea, to England, landing in Falmouth, Cornwall, on 22 June 1940.

Women's Auxiliary Air Force

Although Inayat Khan was deeply influenced by the pacifist teachings of her father, she and her brother Vilayat decided to help defeat Nazi tyranny: "I wish some Indians would win high military distinction in this war. If one or two could do something in the Allied service which was very brave and which everybody admired it would help to make a bridge between the English people and the Indians."[7]

On 19 November 1940, she joined the Women's Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) and, as an aircraftwoman 2nd class, was sent to be trained as a wireless operator. Upon assignment to a bomber training school in June 1941, she applied for a commission in an effort to relieve herself of the boring work there, subsequently being promoted assistant section officer.

Special Operations Executive F Section agent

Later, Inayat Khan was recruited to join F (France) Section of the Special Operations Executive and in early February 1943 she was posted to the Air Ministry, Directorate of Air Intelligence, seconded to First Aid Nursing Yeomanry (FANY), and sent to Wanborough Manor, near Guildford in Surrey, and from there to various other SOE schools for training, including STS 5 Winterfold House, STS 36 Boarmans and STS 52 Thame Park. During her training she adopted the name "Nora Baker". Her superiors held mixed opinions on her suitability for secret warfare, and her training was incomplete. Nevertheless, her fluent French and her competency in wireless operation—coupled with a shortage of experienced agents—made her a desirable candidate for service in Nazi-occupied France. On 16/17 June 1943, cryptonymed 'Madeleine'/W/T operator 'Nurse' and under the cover identity of Jeanne-Marie Regnier, Assistant Section Officer/Ensign Inayat Khan was flown to landing ground B/20A 'Indigestion' in Northern France on a night landing double Lysander operation, code named Teacher/Nurse/Chaplain/Monk. She was met by Henri Déricourt.[8]

She travelled to Paris, and with two other women, Diana Rowden (code named Paulette/Chaplain), and Cecily Lefort (code named Alice/Teacher), joined the Physician network led by Francis Suttill (code named Prosper). Over the next month and a half, all the other Physician network radio operators were arrested by the Sicherheitsdienst (SD), along with hundreds of Resistance personnel associated with Prosper. Colonel Maurice Buckmaster, head of F Section, later claimed that in spite of the danger, Inayat Khan rejected an offer to return to Britain, although it was certainly in SOE's interest that she stay in the field in the aftermath of the round-up of their largest network. As the only remaining wireless operator still at large in Paris, Inayat Khan continued to transmit to London messages from agents of what remained of the Prosper/Physician circuit, a network she also worked to keep intact despite the mass arrests of its members. She was now the most wanted British agent in Paris with SD officers sent out to look for her at subway stations, and an accurate description of her widely circulated among German security officers. With wireless detection vans in close pursuit, Inayat Khan could transmit for only twenty minutes at one time in one place, but constantly moving from place to place, she managed to escape capture while maintaining wireless communication with London: "She refused to abandon what had become the most important and dangerous post in France and did excellent work."[9]

Capture and imprisonment

Inayat Khan was betrayed to the Germans, either by Henri Déricourt or by Renée Garry. Déricourt (code name Gilbert) was an SOE officer and former French Air Force pilot who had been suspected of working as a double agent for the Sicherheitsdienst. Garry was the sister of Henri Garry, Inayat Khan's organiser in the Cinema network (later renamed Phono).[10] Allegedly paid 100,000 francs, Renée Garry's actions have been attributed by some to jealousy due to Garry's suspicion that she had lost the affections of SOE agent France Antelme to Inayat Khan.

On or around 13 October 1943, Inayat Khan was arrested and interrogated at the SD Headquarters at 84 Avenue Foch in Paris. Though SOE trainers had expressed doubts about her gentle and unworldly character, on her arrest she fought so fiercely that SD officers were afraid of her. She was thenceforth treated as an extremely dangerous prisoner. There is no evidence of her being tortured, but her interrogation lasted over a month. During that time, she attempted escape twice. Hans Kieffer, the former head of the SD in Paris, testified after the war that she did not give the Gestapo a single piece of information, but lied consistently.[11] However other sources indicate that she chatted amiably with an out-of-uniform Alsatian interrogator, and provided personal details that enabled the SD to answer random checks in the form of questions about her childhood and family.[12]

Although Inayat Khan did not talk about her activities under interrogation, the SD found her notebooks. Contrary to security regulations, she had copied out all the messages she had sent as an SOE operative (this may have been due to her misunderstanding what a reference to filing meant in her orders, and also the truncated nature of her security course due to the need to insert her into France as soon as possible). Although she refused to reveal any secret codes, the Germans gained enough information from them to continue sending false messages imitating her. London failed to properly investigate anomalies which would have indicated the transmissions were sent under enemy control, in particular the change in the 'fist' (the style of the operator's Morse transmission) though according to M. R. D. Foot, the Sicherheitsdienst were quite adept at faking operators' fists.[12] As a WAAF signaller, Inayat Khan had been nicknamed 'Bang Away Lulu' because of her distinctively heavy-handed style, which was said to be a result of chilblains.[13]

As a result of London's errors, three more agents sent to France were captured by the Germans at their parachute landing, among them Madeleine Damerment, who was later executed.[14] Sonya Olschanezky ('Tania'), a locally recruited SOE agent had learnt of Inayat Khan's arrest and sent a message to London through her fiancé, Jacques Weil, telling Baker Street of her capture and warning HQ to suspect any transmissions from 'Madelaine'. Colonel Maurice Buckmaster ignored the message as unreliable because he did not know who Olschanezky was. As a result, German transmissions from Inayat Khan's radio continued to be treated as genuine, leading to the unnecessary deaths of SOE agents, including Olschanezky herself, who was executed at Natzweiler-Struthof concentration camp on 6 July 1944. When Vera Atkins investigated the deaths of missing SOE agents, she initially confused Inayat Khan with Olschanezky (they were similar in appearance), who was unknown to her, believing that Inayat Khan had been killed at Natzweiler, correcting the record only when she discovered Inayat Khan's fate at Dachau.[15]

On 25 November 1943, Inayat Khan escaped from the SD Headquarters, along with fellow SOE agents John Renshaw Starr and Leon Faye, but was recaptured in the vicinity. There was an air raid alert as they escaped across the roof. Regulations required a count of prisoners at such times and their escape was discovered before they could get away. After refusing to sign a declaration renouncing future escape attempts, Inayat Khan was taken to Germany on 27 November 1943 "for safe custody" and imprisoned at Pforzheim in solitary confinement as a "Nacht und Nebel" ("Night and Fog": condemned to "Disappearance without Trace") prisoner, in complete secrecy. For ten months, she was kept there shackled at her hands and feet.[16]

She was classified as "highly dangerous" and shackled in chains most of the time. As the prison director testified after the war, Inayat Khan remained uncooperative and continued to refuse to give any information on her work or her fellow operatives, although in her despair at the appalling nature of her confinement, other prisoners could hear her crying at night. However, by the ingenious method of scratching messages on the base of her mess cup, she was able to inform another inmate of her identity, giving the name of Nora Baker and the London address of her mother's house.[9]

Execution

On 11 September 1944, Inayat Khan and three other SOE agents from Karlsruhe prison, Yolande Beekman, Eliane Plewman, and Madeleine Damerment, were moved to the Dachau Concentration Camp. In the early morning hours of 13 September 1944, the four women were executed by a shot to the back of the head. Their bodies were immediately burned in the crematorium. An anonymous Dutch prisoner contended, in 1958, that Inayat Khan was cruelly beaten by an SS officer named Wilhelm Ruppert before being shot from behind.[17] Her last word has been recorded as, "Liberté". She was survived by her mother and three siblings.[18][19]

Honours and awards

Inayat Khan was posthumously awarded the George Cross in 1949, and a French Croix de Guerre with silver star (avec étoile de vermeil). As she was still considered "missing" in 1946, she could not be recommended for a Member of the Order of the British Empire,[20] but was Mentioned in Despatches instead in October 1946.[21] Inayat Khan was the third of three Second World War FANY members to be awarded the George Cross, Britain's highest award for gallantry not in the face of the enemy.[18]

At the beginning of 2011, a campaign was launched to raise £100,000 for a bronze bust of her in central London close to her former home.[22] It was claimed that this would be the first memorial in Britain to either a Muslim or an Asian woman,[23] but Inayat Khan had already been commemorated on the FANY memorial in St Paul's Church, Wilton Place, Knightsbridge, London,[24] which lists the 52 members of the Corps who gave their lives on active service.

The unveiling of the bronze bust by HRH The Princess Royal took place on 8 November 2012 in Gordon Square Gardens, London.[25][26]

Inayat Khan is commemorated on a stamp issued by the Royal Mail on 25 March 2014 in a set of stamps about "Remarkable Lives".[27]

George Cross citation

The announcement of the award of the George Cross was made in the London Gazette of 5 April 1949. The full citation reads:[9]

The KING has been graciously pleased to approve the posthumous award of the GEORGE CROSS to:—Assistant Section Officer Nora INAYAT-KHAN (9901), Women's Auxiliary Air Force.

Assistant Section Officer Nora INAYAT-KHAN was the first woman operator to be infiltrated into enemy occupied France, and was landed by Lysander aircraft on 16th June, 1943. During the weeks immediately following her arrival, the Gestapo made mass arrests in the Paris Resistance groups to which she had been detailed. She refused however to abandon what had become the principal and most dangerous post in France, although given the opportunity to return to England, because she did not wish to leave her French comrades without communications and she hoped also to rebuild her group. She remained at her post therefore and did the excellent work which earned her a posthumous Mention in Despatches.

The Gestapo had a full description of her, but knew only her code name "Madeleine". They deployed considerable forces in their effort to catch her and so break the last remaining link with London. After 3 months, she was betrayed to the Gestapo and taken to their H.Q. in the Avenue Foch. The Gestapo had found her codes and messages and were now in a position to work back to London. They asked her to co-operate, but she refused and gave them no information of any kind. She was imprisoned in one of the cells on the 5th floor of the Gestapo H.Q. and remained there for several weeks during which time she made two unsuccessful attempts at escape. She was asked to sign a declaration that she would make no further attempts, but she refused and the Chief of the Gestapo obtained permission from Berlin to send her to Germany for "safe custody". She was the first agent to be sent to Germany.

Assistant Section Officer INAYAT-KHAN was sent to Karlsruhe in November 1943, and then to Pforzheim where her cell was apart from the main prison. She was considered to be a particularly dangerous and unco-operative prisoner. The Director of the prison has also been interrogated and has confirmed that Assistant Section Officer INAYAT-KHAN, when interrogated by the Karlsruhe Gestapo, refused to give any information whatsoever, either as to her work or her colleagues.

She was taken with three others to Dachau Camp on the 12 September 1944. On arrival, she was taken to the crematorium and shot.

Assistant Section Officer INAYAT-KHAN displayed the most conspicuous courage, both moral and physical over a period of more than 12 months.

| George Cross | ||||

| 1939–1945 Star | France and Germany Star | War Medal with Mention in Dispatches |

Croix de Guerre (avec étoile de vermeil) | |

In popular culture

Film

In September 2012, producers Zafar Hai and Tabrez Noorani obtained the film rights to the biography Spy Princess: The Life of Noor Inayat Khan by Shrabani Basu.[28]

Literature

- On 6, September 2010, American poet Stacy Ericson posted a poem entitled "Resistance", dedicated to Noor Inayat Khan and providing a link back to Khan's biography. This may have been the first poem dedicated to Noor Inayat Khan and refers to the isolation and fear shared by those in resistance to oppressive regimes.[29]

- On 3 March 2013, Irfanulla Shariff, an American poet, posted a poem on the internet, "A Tribute To The Illuminated Woman of World War II", dedicated to Inayat Khan. It fully illustrates the life story of this remarkable heroic woman of World War II.[30]

Television

- A Man Called Intrepid (first airdate February 1979), is a six-hour, fact-based miniseries broadcast in Canada on CTV and in the US on NBC which starred David Niven as its protagonist Sir William Stephenson, and Barbara Hershey as Inayat Khan. The following deviations from facts are noted:

- Her capture was attributed to German diligence in sweeping for transmissions, not to betrayal by Déricourt or Garry

- The torture was managed by "Colonel Juergen", a composite character partly based on Wilhelm Ruppert; it is unlikely that a single German military officer would have been in four locations: Paris Gestapo, Karlsruhe prison, Dachau and the Oslo branch of SD (even sequentially)

- During the escape attempt by Khan and Starr (unnamed), Khan reached her transmitter only to discover that she had been set up by Juergen, and that Starr was his plant

- When the fake transmissions were sent in her name, Khan managed to signal her (fictitious) handler and lover Evan Michaelian (played by Michael York) that she was compromised, by giving an incorrect answer to a question which related to a secret she had revealed to him (and Michaelian was able to then tell Stephenson and SOE to retaliate with faked replies)

- Juergen arranged another escape attempt on the route from Karlsruhe to Dachau, and she was executed alone (no mention of Beekman, Plewman, and Damerment) after not being taken in. Also Juergen wept after her execution (which was not likely from Ruppert)

- While Ruppert was executed on 29 May 1946 by the American forces in Germany, Juergen was killed in 1945 in Oslo Harbour by the second of two bombs planted by Michaelian who thus (possibly inadvertently) avenged her execution

- In 2014, PBS aired a 60-minute biographical docudrama entitled Enemy of the Reich: The Noor Inayat Khan Story,[31] executive produced by Alex Kronemer and Michael Wolfe of Unity Productions Foundation[32] and directed by Robert H. Gardner. Grace Srinivasan played the title role.[33]

References

- ↑ "Noorunissa Inayat-Khan". The Message of Hazrat Inayat Khan. 2016. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Noor-un-nisa Inayat Khan". Sufi Order International. 2009. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Tomb of Hazrat Inayat Khan". Delhi Information. 2016. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- ↑ Claims that Ora Ray Baker was related to Christian Science founder Mary Baker Eddy require corroboration.

- ↑ Inayat Khan, Noor (1985). Twenty Jātaka Tales. Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions International. ISBN 9780892813230.

- ↑ Tonkin, Boyd (20 February 2006). "Noor Anayat Khan: The princess who became a spy". The Independent. London, UK. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- ↑ Visram, Rozina (1986). Ayahs, Lascars and Princes: The Story of Indians in Britain 1700–1947. London, UK: Pluto Press. p. 142. ISBN 9780745300740.

- ↑ Brown, Anthony Cave (2007). Bodyguard of Lies. Globe Pequot Press. p. 551. ISBN 978-1-59921-383-5.

- 1 2 3 The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 38578. p. 1703. 5 April 1949.

- ↑ Foot, M. R. D. (2004) [1966]. SOE in France (Revised ed.). London, UK: Whitehall History Publications. pp. 297–299. ISBN 9780714655284.

- ↑ "Timewatch: The Princess Spy". BBC Two. 19 May 2006. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- 1 2 Foot, M. R. D. (1984). SOE: The Special Operations Executive 1940–46. BBC. pp. 138–140. ISBN 9780563201939.

- ↑ Escott, Beryl E. (1991). Mission Improbable : A salute to RAF women of SOE in wartime France. Sparkford, Somerset: P. Stephens. ISBN 9781852602895.

- ↑ "HS 9/836/5: Noor Inayat Khan (1914–44)". The National Archives. 12 May 2003. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- ↑ Helm (2005), pp. 295–296.

- ↑ Visram, Rozina (1986). Ayahs, Lascars and Princes: The Story of Indians in Britain 1700–1947. London, UK: Pluto Press. p. 143. ISBN 9780745300740.

- ↑ Basu, Shrabani (2006). Spy Princess: The Life of Noor Inayat Khan. Sutton Publishing. pp. xx–xxi. ISBN 9780750939652.

- 1 2 Hamilton, Alan (13 May 2006). "Exotic British spy who defied Gestapo brutality to the end". The Times. London, UK. p. 26.

- ↑ Helm, Sarah (7 August 2005). "The Gestapo Killer Who Lived Twice". Sunday Times Magazine. p. 9.

- ↑ "George Cross, George Medal and the Medal of the Order of the British Empire (military): Air Ministry recommendation to the Selection Committee and correspondence (Assistant Section Officer Nora Inayat-Khan, Women's Auxiliary Air Force)", T 351/47, National Archives, Kew.

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 37744. p. 4905. 27 September 1946.

- ↑ Milmo, Cahal (4 January 2011). "Honoured at last, the Indian heroine of Churchill's spy squad". The Independent. Retrieved 4 January 2011.

- ↑ Talwar, Divya (11 January 2011). "Churchill's Asian spy princess comes out of the shadows". BBC News. Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- ↑ "Women's Transport Service". stephen-stratford.co.uk.

- ↑ "Unveiling of the Memorial for Noor Inayat Khan". Noor Inayat Khan Memorial Trust. 8 November 2012. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- ↑ Hutton, Alice (15 November 2012). "Princess Anne unveils bust of forgotten wartime spy whose last word as she faced a firing squad was 'Liberté'". Camden New Journal. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- ↑ "Remarkable Lives Stamp Set at Royal Mail Shop". Royal Mail. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- ↑ Deng, Olivia (5 October 2012). "Shrabani Basu's Spy Princess is optioned by Hollywood". Asia Pacific Arts.

- ↑ Ericson, Stacy (6 September 2010). "Shorter poems — Resistance". stacyericsonauthor.info. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- ↑ Shariff, Irfanulla. "A Tribute To The Illuminated Woman of World War II". Poem Hunter. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- ↑ "One Woman, Many Surprises: Pacifist Muslim, British Spy, WWII Hero". NPR.org. 6 September 2014. Retrieved 26 May 2016.

- ↑ "Enemy of the Reich – The Noor Inayat Khan Story". Unity Productions Foundation. 2016. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- ↑ "Grace Srinivasan". IMDb. Retrieved 26 May 2016.

Further reading

- Marks, Leo (1998). Between Silk and Cyanide: A Codemaker's Story 1941–1945. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-684-86780-X.

- Basu, Shrabani (2006). Spy Princess: The Life of Noor Inayat Khan. Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-3965-6.

- Fuller, Jean Overton (1988). Noor-un-nisa Inayat Khan: Madeleine. East-West Publications. ISBN 9780214653056.

- Binney, Marcus (2003). The Women Who Lived For Danger: The Women Agents of SOE in the Second World War. Coronet Books. ISBN 9780060540876.

- Helm, Sarah (2005). A Life in Secrets: The Story of Vera Atkins and the Lost Agents of SOE. Abacus. ISBN 9780316724975.

- Foot, M. R. D. (2004) [1966]. S.O.E. in France. Frank Cass Publishers. OCLC 227803.

- Baldwin, Shauna Singh (2004). The Tiger Claw. Knopf Canada. ISBN 0-676-97621-2.

- Joffrin, Laurent (2004). La princesse oubliée [All That I Have] (in French). ISBN 0434010634.

- Stevenson, William (1976). A Man Called Intrepid. London, UK: Book Club Associates. ISBN 0151567956.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Noor Inayat Khan. |

- Perrin, Nigel (2016). "Noor Inayat Khan". Special Operations Executive (SOE) Agents in France.

- "Noor Inayat Khan". BBC History. 2015.

- Bari, Shahida (2015). "The Documentary, Codename: Madeleine". BBC World Service.

- "Muslim 'Spy Princess' Honoured in London". aquila-style.com. 12 November 2012.

- Basu, Shrabani (20 February 2006). "Noor Anayat Khan: The princess who became a spy". The Independent.