Nerium

| Nerium | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nerium oleander in flower | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Eudicots |

| (unranked): | Asterids |

| Order: | Gentianales |

| Family: | Apocynaceae |

| Subfamily: | Apocynoideae |

| Tribe: | Wrightieae |

| Genus: | Nerium L. |

| Species: | N. oleander |

| Binomial name | |

| Nerium oleander L. | |

| Synonyms[1][2] | |

| |

Nerium oleander /ˈnɪəriəm ˈoʊliː.ændər/[3] is an evergreen shrub or small tree in the dogbane family Apocynaceae, toxic in all its parts. It is the only species currently classified in the genus Nerium. It is most commonly known as oleander, from its superficial resemblance to the unrelated olive Olea.[Note 1] It is so widely cultivated that no precise region of origin has been identified, though southwest Asia has been suggested. The ancient city of Volubilis in Morocco may have taken its name from the Berber name oualilt for the flower.[4] Oleander is one of the most poisonous commonly grown garden plants.

Description

Oleander grows to 2–6 m (6.6–19.7 ft) tall, with erect stems that splay outward as they mature; first-year stems have a glaucous bloom, while mature stems have a grayish bark. The leaves are in pairs or whorls of three, thick and leathery, dark-green, narrow lanceolate, 5–21 cm (2.0–8.3 in) long and 1–3.5 cm (0.39–1.38 in) broad, and with an entire margin filled with minute reticulate venation web typical to Eudicots. The flowers grow in clusters at the end of each branch; they are white, pink to red,[Note 2] 2.5–5 cm (0.98–1.97 in) diameter, with a deeply 5-lobed fringed corolla round the central corolla tube. They are often, but not always, sweet-scented.[Note 3] The fruit is a long narrow capsule 5–23 cm (2.0–9.1 in) long, which splits open at maturity to release numerous downy seeds.

Habitat and range

N. oleander is either native or naturalized to a broad area from Mauritania, Morocco, and Portugal eastward through the Mediterranean region and the Sahara (where it is only found sporadically), to the Arabian peninsula, southern Asia, and as far east as Yunnan in southern parts of China.[5][6][7][8] It typically occurs around stream beds in river valleys, where it can alternatively tolerate long seasons of drought and inundation from winter rains. Nerium oleander is planted in many subtropical and tropical areas of the world. On the East Coast of the US, it grows as far north as Virginia Beach, Virginia, while in California and Texas it is naturalized as a median strip planting. Because of its durability, Oleander was planted prolifically on Galveston Island in Texas after the disastrous Hurricane of 1900. They are so prolific that Galveston is known as the 'Oleander City'; an annual Oleander festival is hosted every spring.[9] Oleander can be grown successfully outdoors in southern England, particularly in London and mild coastal regions of Dorset and Cornwall.[10]

Ecology

Some invertebrates are known to be unaffected by oleander toxins, and feed on the plants. Caterpillars of the polka-dot wasp moth (Syntomeida epilais) feed specifically on oleanders and survive by eating only the pulp surrounding the leaf-veins, avoiding the fibers. Larvae of the common crow butterfly (Euploea core) also feed on oleanders, and they retain or modify toxins, making them unpalatable to would-be predators such as birds, but not to other invertebrates such as spiders and wasps.

The flowers require insect visits to set seed, and seem to be pollinated through a deception mechanism. The showy corolla acts as a potent advertisement to attract pollinators from a distance, but the flowers are nectarless and offer no reward to their visitors. They therefore receive very few visits, as typical of many rewardless flower species.[11][12] Fears of honey contamination with toxic oleander nectar are therefore unsubstantiated.

Ornamental gardening

Oleander is a vigorous grower in warm subtropical regions, where it is extensively used as an ornamental plant in parks, along roadsides, and as a windbreak. It will tolerate occasional light frost down to −10 °C (14 °F).,[8] though the leaves may be damaged. The toxicity of Oleander renders it deer-resistant. The plant is tolerant of poor soils, salt spray, and sustained drought, although it will flower and grow more vigorously with regular water. Nerium Oleander also responds well to heavy pruning, which should be done in the autumn or early spring to keep plants from becoming unruly.

In cold-winter climates Oleander can be grown in greenhouses and conservatories, or as potted indoor plants that can be kept outside in the summer. Oleander flowers are showy, profuse, and often fragrant, which makes them very attractive in many contexts. Over 400 cultivars have been named, with several additional flower colors not found in wild plants having been selected, including red, pink, yellow, and salmon; white and a variety of pinks are the most common. Double flowered cultivars like 'Mrs Isadore Dyer' or 'Mont Blanc' are enjoyed for their large, rose-like blooms and strong fragrance. Many dwarf cultivars have also been developed, which grow to only about 10' at maturity. In most Mediterranean climates they can be expected to bloom from April through October, with their heaviest bloom usually in May or June.

Therapeutic efficacy

Drugs derived from N. oleander have been investigated as a treatment for cancer, unsuccessfully.[13][14] According to the American Cancer Society, the trials conducted so far have produced no evidence of benefit, while they did cause adverse side effects.[15]

Toxicity

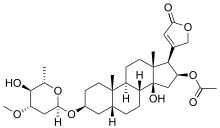

Oleander has historically been considered a poisonous plant because some of its compounds may exhibit toxicity, especially to animals, when consumed in large amounts. Among these compounds are oleandrin and oleandrigenin, known as cardiac glycosides, which are known to have a narrow therapeutic index and can be toxic when ingested.

Toxicity studies of animals administered oleander extract concluded that rodents and birds were observed to be relatively insensitive to oleander cardiac glycosides.[16] Other mammals, however, such as dogs and humans, are relatively sensitive to the effects of cardiac glycosides and the clinical manifestations of "glycoside intoxication".[16][17][18]

However, despite the common "poisonous" designation of this plant, very few toxic events in humans have been reported. According to the Toxic Exposure Surveillance System, in 2002, 847 human exposures to oleander were reported to poison centers in the United States.[19] Despite this exposure level, from 1985 through 2005, only three deaths were reported. One cited death was apparently due to the ingestion of oleander leaves by a diabetic man.[20] His blood indicated a total blood concentration of cardiac glycosides of about 20 μg/l, which is well above the reported fatal level. Another study reported on the death of a woman who self-administered "an undefined oleander extract" both orally and rectally and her oleandrin tissue levels were 10 to 39 μg/g, which were in the high range of reported levels at autopsy.[21] And finally, one study reported the death of a woman who ingested oleander 'tea'.[22] Few other details were provided.

In contrast to consumption of these undefined oleander-derived materials, no toxicity or deaths were reported from topical administration or contact with N. oleander or specific products derived from them. In reviewing oleander toxicity, Lanford and Boor[23] concluded that, except for children who might be at greater risk, "the human mortality associated with oleander ingestion is generally very low, even in cases of moderate intentional consumption (suicide attempts)".[23]

Toxicity studies conducted in dogs and rodents administered oleander extracts by intramuscular injection indicated that, on an equivalent weight basis, doses of an oleander extract with glycosides 10 times those likely to be administered therapeutically to humans are still safe and without any "severe toxicity observed".[24]

In South Indian states such as Tamil Nadu and in Sri Lanka the seeds of related plant with similar local name (Kaneru(S) කණේරු) Cascabela thevetia produce a poisonous plum with big seeds. As these seeds contain cardenolides, swallowing them is one of the preferred methods for suicides in villages.

Effects of poisoning

Ingestion of this plant can affect the gastrointestinal system, the heart, and the central nervous system. The gastrointestinal effects can consist of nausea and vomiting, excess salivation, abdominal pain, diarrhea that may contain blood, and especially in horses, colic.[7] Cardiac reactions consist of irregular heart rate, sometimes characterized by a racing heart at first that then slows to below normal further along in the reaction. Extremities may become pale and cold due to poor or irregular circulation. The effect on the central nervous system may show itself in symptoms such as drowsiness, tremors or shaking of the muscles, seizures, collapse, and even coma that can lead to death.

Oleander sap can cause skin irritations, severe eye inflammation and irritation, and allergic reactions characterized by dermatitis.[25]

Treatment

Poisoning and reactions to oleander plants are evident quickly, requiring immediate medical care in suspected or known poisonings of both humans and animals.[25] Induced vomiting and gastric lavage are protective measures to reduce absorption of the toxic compounds. Charcoal may also be administered to help adsorb any remaining toxins.[7] Further medical attention may be required depending on the severity of the poisoning and symptoms. Temporary cardiac pacing will be required in many cases (usually for a few days) until the toxin is excreted.

Digoxin immune fab is the best way to cure an oleander poisoning if inducing vomiting has no or minimal success, although it is usually used only for life-threatening conditions due to side effects.

Drying of plant materials does not eliminate the toxins. It is also hazardous for animals such as sheep, horses, cattle, and other grazing animals, with as little as 100 g being enough to kill an adult horse.[26] Plant clippings are especially dangerous to horses, as they are sweet. In July 2009, several horses were poisoned in this manner from the leaves of the plant.[27] Symptoms of a poisoned horse include severe diarrhea and abnormal heartbeat. There is a wide range of toxins and secondary compounds within oleander, and care should be taken around this plant due to its toxic nature. Different names for oleander are used around the world in different locations, so, when encountering a plant with this appearance, regardless of the name used for it, one should exercise great care and caution to avoid ingestion of any part of the plant, including its sap and dried leaves or twigs. The dried or fresh branches should not be used for spearing food, for preparing a cooking fire, or as a food skewer. Many of the oleander relatives, such as the desert rose (Adenium obesum) found in East Africa, have similar leaves and flowers and are equally toxic.

Folklore

The alleged toxicity of the plant makes it the center of an urban legend documented on several continents and over more than a century. Often told as a true and local event, typically an entire family, or in other tellings a group of scouts, succumbs after consuming hot dogs or other food roasted over a campfire using oleander sticks.[28]

Garden history

In his book Enquiries into Plants of circa 300 BC, Theophrastus described (among plants that affect the mind) a shrub he called onotheras, which modern editors render oleander; "the root of onotheras [oleander] administered in wine", he alleges, "makes the temper gentler and more cheerful".

The plant has a leaf like that of the almond, but smaller, and the flower is red like a rose. The plant itself (which loves hilly country) forms a large bush; the root is red and large, and, if this is dried, it gives off a fragrance like wine.

In another mention, of "wild bay" (Daphne agria), Theophrastus appears to intend the same shrub.[29]

Oleander was a very popular ornamental shrub in Roman peristyle gardens; it is one of the flora most frequently depicted on murals in Pompeii and elsewhere in Italy. These murals include the famous garden scene from the House of Livia at Prima Porta outside Rome, and those from the House of the Wedding of Alexander and the Marine Venus in Pompeii.[30]

Willa Cather, in her book The Song of the Lark, mentions oleander in this passage:

This morning Thea saw to her delight that the two oleander trees, one white and one red, had been brought up from their winter quarters in the cellar. There is hardly a German family in the most arid parts of Utah, New Mexico, Arizona, but has its oleander trees. However loutish the American-born sons of the family may be, there was never one who refused to give his muscle to the back-breaking task of getting those tubbed trees down into the cellar in the fall and up into the sunlight in the spring. They may strive to avert the day, but they grapple with the tub at last.[31]

Oleander is the official flower of the city of Hiroshima, having been the first to bloom following the atomic bombing of the city in 1945.[32]

It is the provincial flower of Sindh province.

Gallery

N. oleander, found in Tamil Nadu, Chennai

N. oleander, found in Tamil Nadu, Chennai N. oleander bud, found in Tamil Nadu, Chennai

N. oleander bud, found in Tamil Nadu, Chennai N. oleander, found in Tamil Nadu, Chennai

N. oleander, found in Tamil Nadu, Chennai N. oleander, found in Tamil Nadu, Chennai

N. oleander, found in Tamil Nadu, Chennai.jpg) Oleander white flowers, Guntur

Oleander white flowers, Guntur Nerium indicum Mill in China

Nerium indicum Mill in China Oleanders by Vincent van Gogh (oil on canvas, 1888)

Oleanders by Vincent van Gogh (oil on canvas, 1888)

See also

- List of ineffective cancer treatments

- List of plants poisonous to equines

- List of poisonous plants

- Tibesti-Jebel Uweinat montane xeric woodlands

- Yellow oleander

Notes

- ↑ Cf. oleaster

- ↑ The "Yellow Oleander" is Thevetia peruviana.

- ↑ In the past, scented plants were sometimes treated as the distinct species N. odorum, but the character is not constant and it is no longer regarded as a separate taxon.

References

- ↑ "World Checklist of Selected Plant Families, entry for Nerium oleander". Retrieved May 18, 2014.

- ↑ "World Checklist of Selected Plant Families, entry for Nerium". Retrieved May 18, 2014.

- ↑ Sunset Western Garden Book, 1995:606–607

- ↑ "Archaeological Site of Volubilis". African World Heritage Fund. Retrieved 2013-05-12.

- ↑ Pankhurst, R. (editor). Nerium oleander L. Flora Europaea. Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. Retrieved on 2009-07-27.

- ↑ Bingtao Li, Antony J. M. Leeuwenberg, and D. J. Middleton. "Nerium oleander L.", Flora of China. Harvard University. Retrieved on 2009-07-27.

- 1 2 3 INCHEM (2005). Nerium oleander L. (PIM 366). International Programme on Chemical Safety: INCHEM. Retrieved on 2009-07-27

- 1 2 Huxley, A.; Griffiths, M.; Levy, M. (eds.) (1992). The New RHS Dictionary of Gardening. Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-47494-5.

- ↑ http://oleander.org/oleander-history/

- ↑ http://www.telegraph.co.uk/gardening/gardeningadvice/3350060/Gardening-advice-Thorny-problems.html

- ↑ HERRERA, J. (1991). The reproductive biology of a riparian Mediterranean shrub, Nerium oleander L.(Apocynaceae). Botanical journal of the Linnean Society, 106(2), 147-172.

- ↑ Shmida, A., Ivri, Y., and Cohen, D. The enigma of the oleander. Eretz VeTeva, January–February 1995 (in Hebrew).

- ↑ Henary, HA; Kurzrock, R; Falchook, GS; et al. (2011). "Final Results of a First-in-Human Phase 1 Trial of PBI-05204, and Inhibitor of AKT, FGF-2, NF-Kb and P70S6K in Advanced Cancer Patients". J Clin Oncol. 29 (supplement; abstract 3023).

- ↑ Newman, R. A.; Yang, P.; Pawlus, A. D.; Block, K. I. (2008). "Cardiac Glycosides as Novel Cancer Therapeutic Agents". Molecular Interventions. 8 (1): 36–49. doi:10.1124/mi.8.1.8. PMID 18332483.

- ↑ "Oleander Leaf". American Cancer Society. Retrieved April 2013. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - 1 2 Szabuniewicz M, Schwartz WL, McCrady JD, et al. (1972). "Experimental oleander poisoning and treatment". Southwestern Vet. 25 (2): 105–114.

- ↑ Szabuniewicz, M., Schwartz, W.L., McCrady, J.D., Russell, L.H. and Camp, B.J. (1971) Treatment of experimentally induced oleander poisoning. Arch. Int. Pharmacodyn. Ther. 189, 12–21.

- ↑ Hougen, T.J., Lloyd, B.L. and Smith, T.W. (1979) Effects of inotropic and arrhythmogenic digoxin doses and of digoxin-specific antibody on myocardial monovalent cation trans-port in the dog. Circ. Res. 44, 23–31.

- ↑ Watson, William A., et al. 2003. 2002 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers Toxic Exposure Surveillance System. American Journal of Emergency Medicine 21 (5): 353-421.

- ↑ Wasfi, Ibrahim A.; Zorob, Omar; Al Katheeri, Nawal A.; Al Awadhi, Anwar M. (2008). "A fatal case of oleandrin poisoning". Forensic Science International. 179 (2–3): e31–6. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2008.05.002. PMID 18602779.

- ↑ Blum, L. M. & F. Reiders (1987). "Oleandrin distribution in a fatality from rectal and oral Nerium oleander extract administration". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 11 (5): 219–221. doi:10.1093/jat/11.5.219. PMID 3682781.

- ↑ Haynes, B. E., H. A. Bessen & W. D. Wightman (1985). "Oleander tea: herbal draught of death". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 14 (4): 350–353. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(85)80103-7. PMID 4039113.

- 1 2 S. D. Langford & P. J. Boor (1996). "Oleander toxicity: an examination of human and animal toxic exposures". Toxicology. 109 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1016/0300-483X(95)03296-R. PMID 8619248.

- ↑ Rhodes JW. Non-GLP Single Dose Lethality Assessment of Nerium Oleander (NOI) by Intramuscular Administration in the Rat. Southwest Research Institute Project 12-7547-029.

- 1 2 Goetz, Rebecca. J. (1998). "Oleander". Indiana Plants Poisonous to Livestock and Pets. Cooperative Extension Service, Purdue University. Retrieved on 2009-07-27.

- ↑ Knight, A. P. (1999). "Guide to Poisonous Plants: Oleander". Colorado State University. Retrieved on 2009-07-27.

- ↑ Trevino, Monica. 2009. Dozens of horses poisoned at California farm. CNN: Crime. Retrieved on 2009-08-03

- ↑ Mikkelson, Barbara (2011-07-31). "Oleander Poisoning: snopes.com". Snopes.com. Retrieved 2015-11-29.

- ↑ Theophrastus. Inquiry into Plants, A. F. Hort, tr. Loeb Classical Library. pp. I.9.3, IX.19.1.

- ↑ Farrar, Linda (1998).'Ancient Roman Gardens,' 141-2,143-9.

- ↑ Cather, Willa (1915). "IV". The Song of the Lark. Project Gutenberg. p. 26.

- ↑ http://arnoldia.arboretum.harvard.edu/pdf/articles/892.pdf

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nerium. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Nerium |

- Clemson University: Oleander Facts. Retrieved on 2009-07-27.

- International Oleander Society: Information on Oleander toxicity. Retrieved on 2009-07-27.

- Barcelona Botanic Gardens: Plants of North Africa. Retrieved on 2009-07-27.

- Erwin, Van den Enden. 2004. Illustrated Lecture Notes on Tropical Medicine. Medical problems caused by plants: Plant Toxins, Cardiac Glycosides. Prince Leopold Institute of Tropical Medicine. Retrieved on 2009-07-27.

- Desai, Umesh R. Cardiac glycosides. Virginia Commonwealth University. School of Pharmacy. Retrieved on 2009-07-27.

- Snopes: Legend of Oleander-poisoning at Campfire. Retrieved on 2009-07-27.

- Distribution over the world, University of Helsinki