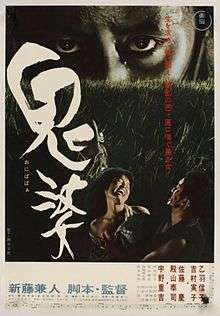

Onibaba (film)

| Onibaba | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Kaneto Shindo |

| Produced by | Toshio Konya[1] |

| Screenplay by | Kaneto Shindo |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Hikaru Hayashi[2] |

| Cinematography | Kiyomi Kuroda[2] |

| Edited by | Toshio Enoki[2] |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Toho |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 102 minutes[2] |

| Country | Japan |

| Language | Japanese |

Onibaba (鬼婆, literally Demon Hag) is a 1964 Japanese historical drama horror film. It was written and directed by Kaneto Shindo. The film is set during a civil war in the fourteenth century. Nobuko Otowa and Jitsuko Yoshimura play two women who kill soldiers to steal their possessions.

Plot

The film is set somewhere in Japan, in the mid-fourteenth century during a period of civil war. Two wounded soldiers flee from pursuers on horse in thick reeds which are taller than a man. Suddenly the soldiers are killed with spears by unseen assailants. Two women appear, take the armour and weapons, and drop the bodies in a hole. The women return to a small hut. The next day they take the armor and weapons to a merchant named Ushi (Taiji Tonoyama) and trade them for food. The merchant tells them news of a war. Ushi tries to seduce the older woman in vain. A neighbor named Hachi (Kei Satō), who has been at war, returns. The older woman (Nobuko Otowa) asks Hachi about her son, who was forced to be a soldier along with Hachi. The son is the husband of the younger woman (Jitsuko Yoshimura). Hachi tells about his experience in two fights, where general Takauji Ashikaga attacked his division. He says that the younger woman's husband had been killed in the fighting three days earlier when surrounded at the Battle of Minatogawa.

One beautiful day the three, who are out at the lake talking and minding their own business, see two samurai chasing one another and fighting on horseback. They jump in the lake and keep fighting, swimming closer to the three as they go. As one samurai comes close to them, asking for help, Hachi stabs him with his spear. He then orders the women to get the other man, whom they drown in the lake. The two then take their armour as before, sell it to Ushi, and have a good meal. Hachi seduces the young woman. She sneaks out of her hut every night to have sex with him. The older woman learns of the relationship. She tries to sleep with Hachi, then pleads with him to not take the young woman away since she cannot kill without her help.

One night, while Hachi and the young woman are together, a lost samurai in a demon --Hannya- mask (Jūkichi Uno) forces the older woman to guide him out of the swamp. She tricks him into plunging to his death in the pit where the women dispose of their victims. She climbs down and steals the samurai's possessions and, with great difficulty, his mask. Under the mask he is disfigured.

At night, the older woman dons the mask and frightens the young woman away from Hachi. During a storm, the older woman terrifies the young woman with the mask, but Hachi finds the daughter-in-law and again has sex with her in the grasses as the old woman watches from afar. Hachi returns to his hut. He finds a man in his hut. The man kills Hachi.

The older woman discovers that, after getting wet in the rain, the mask is impossible to remove. She reveals her scheming to the young woman and pleads with her to help take off the mask. The young woman agrees to remove the mask after the older woman promises not to interfere with her relationship with Hachi. The young woman breaks off the mask with a hammer. Under the mask, the older woman's face is covered with sores. The young woman thinks the older woman has turned into a demon, and runs from her; the older woman runs after her, crying out that she is a human being, not a demon. The young woman leaps over the pit, and as the older woman leaps after her the film ends.

Cast

Most of the cast consisted of members of Shindo's regular group of performers, Nobuko Otowa, Kei Satō, Taiji Tonoyama, and Jūkichi Uno. This was Jitsuko Yoshimura's only appearance in a Shindo film. The two women do not have names even in the script, but are merely described as "middle-aged woman" and "young woman".[3]

- Nobuko Otowa as Older woman

- Jitsuko Yoshimura as Younger woman

- Kei Satō as Hachi

- Taiji Tonoyama as Ushi

- Jūkichi Uno as the masked warrior

Production

The story takes place shortly after the Battle of Minatogawa which began a period of over 50 years of civil war, the Nanboku-chō period (1336 to 1392). Hachi tells of an attack from general Takauji Ashikaga, who came to power in the 1330s.

The story of Onibaba was inspired by the Shin Buddhist parable of yome-odoshi-no men (嫁おどしの面) (bride-scaring mask) or niku-zuki-no-men (肉付きの面) (mask with flesh attached), in which a mother used a mask to scare her daughter from going to the temple. She was punished by the mask sticking to her face, and when she begged to be allowed to remove it, she was able to take it off, but it took the flesh of her face with it.[4]

Kaneto Shindo wanted to film Onibaba in a field of susuki grass. He sent out assistant directors to find suitable locations.[5] Once a location was found near a river bank at Inba-Numa in Chiba, they put up prefabricated buildings to live in.[6] Filming started on 30 June 1964 and continued for three months.[7]

They had a rule that if somebody left they would not get any pay, to keep the crew motivated to continue. Shindo included dramatized scenes of the dissatisfaction on the set as part of the 2000 film By Player.

To film night scenes inside the huts, they would put up screens to block the sun, and changing the shot would require setting the screens in a completely different spot.[8]

Kaneto Shindo said that the effects of the mask on those who wear it are symbolic of the disfigurement of the victims of the Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the film reflecting the traumatic effect of this visitation on post-war Japanese society.[5]

The film contains some sequences filmed in slow motion.[9]

The scenes of the older woman descending in to the hole had to be shot using an artificial "hole" built above ground with scaffolding, since holes dug in the ground at the location site would immediately fill with water.[7]

Score

Onibaba's score is by Shindo's long-term collaborator Hikaru Hayashi. The background and title music consists of Taiko drumming combined with jazz.[10][11]

Release

Onibaba was released in Japan on November 21, 1964 where it was distributed by Toho.[2] The film was released in the United States by Toho International with English subtitles on February 4, 1965.[2] An English-dubbed version was produced by Toho, but any actual release of it is undetermined.[2] On the films initial theatrical release in the United Kingdom, the film was first rejected by the BBFC on its first submission, and then released in a heavily edited form after its second submission."[12]

Home media

It was released as a Region 1 DVD on March 16, 2004 in the Criterion Collection.[11] A Region 2 DVD was released in 2005 as part of the Masters of Cinema series.

Reception

From a contemporary review, the Monthly Film Bulletin" noted that "Shindo obviously likes to milk his situations for all they are worth-and then some." noting that "Onibaba has the same striking surface as [Ningen and The Naked Island]." and that the film "has the same tendency to fall apart if examined too closely".[13] The review praised Kuroda's "fine photography" but noted that nothing else "in the film quite matches this opening among the reeds, or its aftermath in the ruthless stripping of the victims and disposal of their corpses, except perhaps the encounter between the old woman and the General."[13]

A. H. Weiler of the New York Times described the film's raw qualities as "neither new nor especially inventive to achieve his stark, occasionally shocking effects. Although his artistic integrity remains untarnished, his driven rustic principals are exotic, sometimes grotesque figures out of medieval Japan, to whom a Westerner finds it hard to relate."[14] The review noted that Shindo's "symbolism, which undoubtedly is more of a treat to the Oriental than the Occidental eye and ear, may be oblique, but his approach to amour is direct...the tale is abetted by Hiyomi Kuroda's cloudy, low-key photography and Hikaru Kuroda's properly weird background musical score. But despite Mr. Shindo's obvious striving for elemental, timeless drama, it is simply sex that is the most impressive of the hungers depicted here."[14]

Critics disagree on the genre of the film. While Onibaba is regarded a "period drama" by David Robinson,[15] or "stage drama" by Japanese film scholar Keiko I. McDonald,[16] Phil Hardy included it in his genre compendium as a horror film,[17] and Chuck Stephens describes it as an erotic-horror classic.[18] Writing for Sight & Sound, Michael Brooke noted that "Onibaba's lasting greatness and undimmed potency lie in the fact that it works both as an unnervingly blunt horror film (and how!) and as a far more nuanced but nonetheless universal social critique that can easily be applied to an parallel situation"[12]

Peter Bradshaw in The Guardian says "Onibaba is a chilling movie, a waking nightmare shot in icy monochrome, and filmed in a colossal and eerily beautiful wilderness".[4] He comments on the photography "The action of the movie is interspersed with brilliantly composed, almost abstract compositions of the wasteland itself" and summarizes "Onibaba deserves something more than cult status." Jonathan Rosenbaum describes it as "creepy, interesting, and visually striking".[19]

Keiko I. McDonald says that the film contains elements of the Noh theatre. She notes that the han'nya mask "is used to demonize the sinful emotions of jealousy and its associative emotions" in Noh plays, and that the differing camera angles at which the mask is filmed in Onibaba are similar to the way in which a Noh performer uses the angle of the mask to indicate emotions.[20] Other reviewers also speculate about Noh influences on the film.[21][22]

References

- ↑ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 214.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Galbraith IV 2008, p. 215.

- ↑ Shindo 1993, p. 242

- 1 2 Bradshaw, Peter (15 October 2010). "Sex, death and long grass in Kaneto Shindo's Onibaba". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- 1 2 Shindo, Kaneto (Director) (2008-05-15). Onibaba, DVD Extra: Interview with the director (DVD). Criterion Collection.

- ↑ Shindo, Kaneto (2008). Ikite iru kagiri Watashi no Rirekisho [While I live: my resume] (in Japanese). Nihon Keizai Shimbunsha. ISBN 978-4-532-16661-8.

- 1 2 Shindo 1993, pp. 149–187

- ↑ Kuroda, Kiyomi (Cinematography) (2008-05-15). Onibaba, DVD Extra: Making of feature (DVD). Criterion Collection.

- ↑ McDonald 2006, p. 113: a sudden slowing in the shot

- ↑ Film 4. "Onibaba (1964) - Film Review from Film4". Film 4. Retrieved 3 September 2012.

- 1 2 "The Criterion Collection: Onibaba by Kaneto Shindo".

- 1 2 Brooke, Michael (April 2013). "Onibaba". Sight & Sound. Vol. 23 no. 4. British Film Institute. p. 115.

- 1 2 Milne, T.M. (1966). "Onibaba (The Hole), Japan, 1964". Monthly Film Bulletin. Vol. 33 no. 384. British Film Institute. pp. 180–181.

- 1 2 Weiler, A.H. (February 10, 1965). "The Hole (1964) Onibaba at Toho". New York Times. Retrieved 3 September 2012.

- ↑ Robinson, David (1975). World cinema: a short history. Methuen Young Books. p. 340. ISBN 978-0416183306.

- ↑ McDonald 2006, p. 109: Onibaba strikes us as kind of stage drama taking its cues from folklore

- ↑ Hardy, Phil (1996). The Aurum Film Encyclopedia: Horror. Aurum Press. p. 165.

- ↑ Stephens, Chuck (March 15, 2004). "Black Sun Rising". Criterion Collection. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- ↑ Rosenbaum, Jonathan. "Onibaba". Chicago Reader. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- ↑ McDonald 2006, p. 116

- ↑ Lowenstein, Adam (2005). Shocking Representation: Historical Trauma, National Cinema, and the Modern Horror Film. Columbia University Press. p. 101.: "Shindo's use of the hannya mask and reliance on heavy drumming punctuated by human cries for Onibaba's score […] are direct quotations of Noh style."

- ↑ Cuntz, Vera. "SheDevils - Kaneto Shindôs Onibaba & Kuroneko" (in German). Ikonen magazin. Retrieved 9 September 2012.: "Die Filme [Onibaba and Kuroneku] folgen in ihrer Schauspielkunst, Erzählstruktur und Inhalt den klassischen japanischen Nô-Stücken." ("These Films [Onibaba and Kuroneku] follow classic Japanese Noh Plays in the ways of acting, narrative structure and content.")

Bibliography

- Galbraith IV, Stuart (2008). The Toho Studios Story: A History and Complete Filmography. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 1461673747.

- Shindo, Kaneto (8 November 1993). Shindō Kaneto no sokuseki: sei to sei. 3. Iwanami Shoten. ISBN 4-00-003763-3.

- McDonald, Keiko (2006). Reading a Japanese film: Cinema in context. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0824829933.

- Thompson, Nathaniel (2006). DVD Delirium: The International Guide to Weird and Wonderful Films on DVD; Volume 3. Godalming, England: FAB Press. pp. 407–408. ISBN 1-903254-40-X.

External links

- Onibaba at AllMovie

- Onibaba at the Internet Movie Database

- Onibaba at the Japanese Movie Database

- Onibaba at Rotten Tomatoes

- Kei Satō's home movies of the production of Onibaba on YouTube