Operation Homecoming

| Operation Homecoming | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

USAF Capt. Robert Parsels at Gia Lam Airport, repatriated during Operation Homecoming | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

Operation Homecoming was the return of 591 American prisoners of war (POWs) held by North Vietnam following the Paris Peace Accords that ended U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War.

Operation

On January 27, 1973, Henry Kissinger (then assistant to the President for national security affairs) agreed to a ceasefire with representatives of North Vietnam that provided for the withdrawal of American military forces from South Vietnam. The agreement also postulated for the release of nearly 600 American prisoners of war (POWs) held by North Vietnam and its allies within 60 days of the withdrawal of U.S. troops.[1] The deal would come to be known as Operation Homecoming and was divided into three phases. The first phase required the initial reception of prisoners at three release sites: POWs held by the Viet Cong (VC) were to be flown by helicopter to Saigon, POWs held by the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) were released in Hanoi, and the three POWs held in China were to be freed in Hong Kong. The former prisoners were to then be flown to Clark Air Base in the Philippines where they were to be processed at a reception center, debriefed, and receive a physical examination. The final phase was the relocation of the POWs to military hospitals.[2]

On Feb. 12, 1973, three C-141 transports flew to Hanoi, North Vietnam, and one C-9A aircraft was sent to Saigon, South Vietnam to pick up released prisoners of war. The first flight of 40 U.S. prisoners of war left Hanoi in a C-141A, later known as the "Hanoi Taxi" and now in a museum.

From February 12 to April 4, there were 54 C-141 missions flying out of Hanoi, bringing the former POWs home.[3] During the early part of Operation Homecoming, groups of POWs released were selected on the basis of longest length of time in prison. The first group had spent 6–8 years as prisoners of war.[4] The last POWs were turned over to allied hands on March 29, 1973 raising the total number of Americans returned to 591.

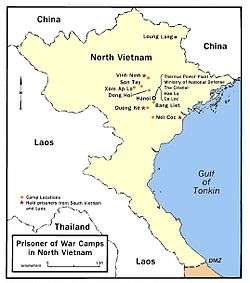

Of the POWs repatriated to the United States a total of 325 of them served in the United States Air Force, a majority of which were bomber pilots shot down over North Vietnam or Viet Cong controlled land. The remaining 266 consisted of 138 United States Naval personnel, 77 soldiers serving in the United States Army, 26 United States Marines, and 25 civilian employees of American government agencies. A majority of the prisoners were held at camps in North Vietnam, however some POWs were held in at various locations throughout Southeast Asia. A total of 69 POWs were held in South Vietnam by the Viet Cong and would eventually leave the country aboard flights from Loc Ninh, while 9 POWs were released from Laos, as well as an additional 3 from China. The prisoners returned included future politicians Senator John McCain of Arizona and Representative Sam Johnson of Texas.[5]

According to John L. Borling, a former POW returned during Operation Homecoming, stated that after being flown to Clark Air Base, hospitalized, and debriefed, many of the doctors and psychologists were amazed by the resiliency of a majority of the men. Some of the repatriated soldiers, including Borling and John McCain, did not retire from the military, but instead decided to further their careers in the armed forces.[6]

The Kissinger Twenty

The culture of the POWs held at the infamous Hanoi Hilton prison was on full display with the story that would come to be known as the “Kissinger Twenty”. One of the tenets of the agreed upon code between those held at the Hanoi Hilton stipulated that the POWs, unless seriously injured, would not accept an early release. The rule entailed that the prisoners would return home in the order that they were shot down and captured. The POWs held at the Hanoi Hilton were to deny early release because the communist government of North Vietnam could possibly use this tactic as propaganda or as a reward for military intelligence.

The first round of POWs to be released in February 1973 mostly included injured soldiers in need of medical attention. Following the first release, twenty prisoners were then moved to a different section of the prison, but the men knew something was wrong as several POWs with longer tenures were left in their original cells. After discussions the twenty men agreed that they should not have been the next POWs released as they estimated it should have taken another week and a half for most of their discharges and came to the conclusion that their early release would likely be used for North Vietnamese propaganda. Consequently, in adherence with their code, the men did not accept release by refusing to follow instructions or put on their clothes. Finally, on the fifth day of protest Colonel Norm Gaddis, the senor American officer left at the Hanoi Hilton, went to man’s cell and gave them a direct order that they would cooperate. The men followed orders, but with the stipulation that no photographs were to be taken of them.

It turned out that when Henry Kissinger went to Hanoi after the first round of releases the North Vietnamese gave him a list of the next 112 men scheduled to be sent home. They asked Kissinger to select twenty more men to be released early as a sign of good will. Unaware of the code agreed upon by the POWs, Kissinger ignored their shot down dates and circled twenty names at random.[7]

Aftermath

Overall, Operation Homecoming did little to satisfy the American public’s need for closure on the war in Vietnam. After Operation Homecoming, the U.S. still listed about 1,350 Americans as prisoners of war or missing in action and sought the return of roughly 1,200 Americans reported killed in action and body not recovered.[8] These missing personnel would become the subject of the Vietnam War POW/MIA issue for years to come. As of November 2015, the Department of Defense still claimed there were 516 unaccounted for U.S. Army personnel, of which 21 are believed to have been prisoners who died while in captivity but whose remains have never been recovered.[9]

In addition, the return of the nearly 600 POWs further polarized the sides of the American public and media. A large number of Americans viewed the recently freed POWs as heroes of the nation returning home, reminiscent of the celebrations following World War II. Others approached the situation with apprehension, questioning if treating these men as heroes served to distort and obscure the truth about the war. A majority of the POWs returned in Operation Homecoming were in fact bomber pilots shot down over enemy territory carrying out the campaign of waged against civilian targets located in Vietnam and Laos. Some felt these men deserved to be treated as war criminals or left in the North Vietnamese prison camps.[10] No matter the opinion of the public, the media became infatuated with the men returned in Operation Homecoming who were bombarded with questions concerning life in the VC and NVA prison camps. Topics included a wide range of inquiries about sadistic guards, secret communication codes among the prisoners, testimonials of faith, and debates over celebrities and controversial figures.[11]

The Army, Navy, Air Force, Marines, and the U.S. Department of State each had liaison officers dedicated to prepare for the return of American POWs well in advance of their actual return. These liaison officers worked behind the scenes traveling around the United States assuring the returnees' well being. They also were responsible for debriefing POWs to discern relevant intelligence about MIAs and to discern the existence of war crimes committed against them.[12][13] Each POW was also assigned their own escort to act as a buffer between “past trauma and future shock”.[14] However, access to the former prisoners was screened carefully and most interviews and statements given by the men were remarkably similar, leading many journalists to believe that the American government and military had coached them beforehand. Izvestia, a Russian news service, even accused the Pentagon of brainwashing the men involved in order to use them as propaganda, while some Americans claimed the POWs were collaborating with the communists or had not done enough to resist pressure to divulge information under torture.[15] The former prisoners were slowly reintroduced, issued their back pay, and attempted to catch up on social and cultural events that were now history. Many of the returned POWs struggled to become reintegrated with their families and the new American culture as they had been held in captivity for anywhere between a year to almost ten years. The men had missed events including the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy, the race riots that broke out in cities from coast to coast in 1968, the political demonstrations and anti-war protests, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin walking on the moon, and the release of The Godfather.[16]

The returning of POWs was often a mere footnote following most other wars in U.S. history, yet those returned in Operation Homecoming provided the country with an event of drama and celebration. Operation Homecoming initially ignited a torrent of patriotism that had not been seen at any point during the Vietnam War. Overall, the POWs were warmly received as if to atone for the collective American guilt for having ignored and protested the majority of soldiers who had served in the conflict and already returned home.[17] The joy brought by the repatriation of the 591 Americans did not last for long due to other major news stories and events. By May 1973, the Watergate scandal dominated the front page of most newspapers causing the American public’s interest to wane in any story related to the war in Vietnam. Correspondingly, Richard Nixon and his administration began to focus on salvaging his presidency rather than saving the world from communism.[18]

Many worried that Homecoming hid the fact that people were still fighting and dying on the battlefields of Vietnam and caused the public to forget about the over 50,000 American lives the war had already cost.[19] Veterans of the war had similar thoughts concerning Operation Homecoming with many stating that the ceasefire and returning of prisoners brought no sense of an ending or closure.[20]

Remembrance

The plane used in the transportation of the first group of prisoners of war, a C-141 commonly known as the Hanoi Taxi (serial number 66-0177), has been altered several times since February 12, 1973. Nevertheless, the aircraft has been maintained as a flying tribute to the POWs and MIAs of the Vietnam War and is now housed at the National Museum of the United States Air Force.[21] The Hanoi Taxi was officially retired at Wright Patterson Air Force Base on May 6, 2006, just a year after it was used to evacuate the areas devastated by Hurricane Katrina.

Operation Homecoming has been largely forgotten by the American public, yet ceremonies commemorating the 40th anniversary were held at United States military bases and other locations throughout Asia and the United States.[22]

Notes

- ↑ Kutler, Stanley I. (1996). Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. p. 442. ISBN 0-13-276932-8. OCLC 32970270.

- ↑ Olson, James S. (2008). In Country: The Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War. New York: Metro Books. p. 427. ISBN 978-1-4351-1184-4. OCLC 317495523.

- ↑ Donna Miles (12 February 2013). "Operation Homecoming for Vietnam POWs Marks 40 Years". American Forces Press Service. U.S. Department of Defense. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

- ↑ "Operation Homecoming". National Museum of the U.S. Air Force. United States Air Force. 28 April 2009. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

- ↑ "Operation Homecoming for Vietnam POWs marks 40 years".

- ↑ Borling, John (2013). Taps on the Walls: Poems from the Hanoi Hilton. Chicago: Master Wings Publishing LLC, , an imprint of the Pritzker Military Library. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-61565905-3. OCLC 818738145.

- ↑ Fretwell, Peter and Taylor Baldwin Kiland (2013). Lessons from the Hanoi Hilton: Six Characteristics of High-Performance Teams. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. p. 111-114. ISBN 978-1-61251-217-4. OCLC 813910294.

- ↑ "Vietnam War Accounting History". Defense Prisoner of War/Missing Personnel Office. Retrieved 2008-11-22.

- ↑ "Operation Homecoming: Repatriation of American Prisoners of War in Vietnam Described".

- ↑ Killen, Andreas (2006). 1973 Nervous Breakdown: Watergate, Warhol, and the Birth of Post-Sixties America. New York: Bloomsbury. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-59691-059-1. OCLC 61453885.

- ↑ Killen, 80.

- ↑ Senate Select Committee - XXIII

- ↑ Vietnam War Internet Project

- ↑ Killen, 84.

- ↑ Killen, 84-85.

- ↑ "See the Emotional Return of Vietnam Prisoners of War in 1973".

- ↑ Botkin, Richard (2009). Ride the Thunder: A Vietnam War Story of Honor and Triumph. Los Angeles: WND. p. 500. ISBN 9781935071051. OCLC 318413266.

- ↑ Botkin, 503.

- ↑ Killen, 97.

- ↑ Killen, 103-104.

- ↑ "Operation Homecoming Part 2: Some History".

- ↑ "Vietnam War POWs Come Home – 40th Anniversary".

Sources

| Vietnam War timeline |

|---|

|

↓ Viet Cong created │ 1955 │ 1956 │ 1957 │ 1958 │ 1959 │ 1960 │ 1961 │ 1962 │ 1963 │ 1964 │ 1965 │ 1966 │ 1967 │ 1968 │ 1969 │ 1970 │ 1971 │ 1972 │ 1973 │ 1974 │ 1975 |