Orc (Blake)

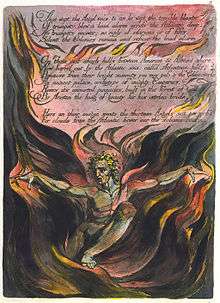

Orc is a proper name for one of the characters in the complex mythology of William Blake. Unlike the medieval sea beast, or Tolkien's humanoid monster, his Orc is a positive figure, the embodiment of rebellion, and stands opposed to Urizen, the embodiment of tradition.

In Blake's illuminated book America a Prophecy, Orc is described by his mythic opponent, "Albion's Angel" as the "Lover of Wild Rebellion, and transgressor of God's Law". He symbolizes the spirit of rebellion and freedom, which provoked the French Revolution.

Background

The name Orc is possibly an anagram of the word cor (heart), in that he was stated in Blake's myth to be born of Enitharmon's heart, or orca (whale) because he sometimes takes the form of a whale. Orcus is also the Latin word for Hell, and Orc is presented as a rebellious, Luciferian character. He was created to serve as Blake's analysis of the revolutions in the United States and France.[1]

Character

In Blake's myth, Orc is seen as the first child of Los with Enitharmon and sometimes either replaced in that position by another or not mentioned as a child at all. In the Four Zoas, the children of Los represent a just form of wrath, pity, frustrated desire and logic, which serve as an analysis of Orc's being. Orc's creation was based on the split between Los and Enitharmon, and he transformed from a worm into the form of a serpent. Based on Orc's relationship with Enitharmon, there is a split between him and Los. Los uses the Chains of Jealousy to bind Orc upon a mountain, and Orc becomes part of the rock. While bound, his imagination is able to exist in a cave located in Urizen's kingdom, which wakes up Urizen. When Urizen seeks out Orc, Orc is freed as he changes into a serpent. The form is corrupted and he is turned into a satanic image. Orc spends his time rebelling against Urizen, and it is only when Urizen stops fighting Orc that Orc is able to become Luvah.[4]

Orc is a force of revolution, revival, and of passion who is the polar opposite to Urizen, the cruel and tyrannous god. Orc is the force of new life in the cycle and Urizen represents the older version of Orc that dies at the end of the cycle. As such, Orc and Urizen appear in their evolution from one to the other in the "Seven Eyes of God", or the seven historical cycles of Blake's myth. Each cycle is divided into three phases, which begins with Orc's birth and then describes Orc's binding, which is connected to the time in a human's life where they are at their imaginative greatness. This is followed by the creation of abstract religion and a view of the universe as mechanical. This is then followed by rationalism, which led to Aristotle, Bacon, Locke and other empirical-based scientists. The second phase is where Urizen takes over the fallen world, which is represented by the Enlightenment in the seventh cycle. This leads to materialism, the death of the soul, and warfare. This phase ends with prophets declaring that Orc will appear. The third phase describes an Orc's crucifixion and a return of human life to nature.[5]

The character Orc is connected to the Biblical serpent, the image of being hanged on a dead tree, and to the sun. Of the latter, Orc's hair is like the sun and connects Orc to other stories, including that of Samson or of the death of the god Balder. Likewise, the tree image is similar to Odin's being speared and hanged upon a gallows-tree as a sacrifice. Since Odin is the a hanged god and a tyrant, the image further connects the image of Orc with that of Urizen. Another image connected to Orc is that of the spear, a phallic symbol connected to the imagination. Orc uses the spear to attack Urizen, and the image also connects Orc to both Jesus and Odin as sacrifices to themselves. Like Jesus, Orc is also born around the winter solstice, a time when the sun is unable to warm the cold earth.[6]

Orc is also connected to the inner workings of the human self. After Blake renounced the Orc men, the revolutionary leaders who he thought were like Orc, he distrusted all hero worship. Likewise, Blake believed that the imagination, represented by Orc, was purely mental and could not have the same form as a physical thing. Instead, it was part of the divine energy in man. As such, Orc is an internal life cycle that ends with a rebirth of the self. In general, Orc represented the freedom of the self in a Promethean manner, which connects Orc to Milton's version of Satan. In Blake's version, the true Satan was God, who created the physical reality, and the Satan/Orc figure represents the human desire which is transformed into accepting of law and reason. As such, Blake dismisses Milton's epic as lacking a hero and keeps Orc from being seen as a heroic figure.[7]

Appearances

In America a Prophecy (1793), Orc is described as a threat to the British colonies in America and to society. The angel of Albion sees Orc as an antichrist figure, and Orc views the prince of Albion as a dragon. During the work, Orc has an apocalyptic vision where the empire is destroyed and the oppressors of the world are stopped. Following the vision, Orc is able to get the Americans to rise up in revolution and they begin to attack their oppressors through a mental revolution.[10] In Europe a Prophecy (1794), Orc is connected to the revolution in France but it is Los who calls the people to revolution.[11] In The Song of Los, Orc provokes thought within the second half, "Asia", which unsettles the kings of earth, and Orc is described as raging across Europe.[12] In these continental works, Los and Orc are seen as describing an apocalypse that would result in freedom.[13]

In The Book of Urizen, the African civilization ends along with the third cycle, describing Adam and Eve, ending. Orc, symbolized as the serpent in the Garden of Eden, is cursed. This is followed in The Book of Ahania of a new cycle beginning in Asia, which parallels Exodus. Within the Israeli civilization, an Orc and an Urizen figure battles against each other with Orc representing a pillar of fire that guides the Israelites during the night while Urizen is a pillar of cloud that seeks to mislead them. Urizen is able to win over the Israelites by giving them the ten commandments and moral laws. These commandments are attacked by Orc in America a Prophecy.[14]

Later in Vala, Orc describes the divided aspects of the soul, which, in Blake's mythological system, God has a twofold essence that is capable of good and evil. This idea parallels Blake's personal belief that there was a division within himself.[15] In this later work, Orc is born during the winter solstice and Urizen begins to search for him. Urizen, during this time, becomes witness to the life cycles of which Orc is a part. When Urizen finally reaches Orc, the view of the Orc cycle is described in a deistic manner, a perspective which is arguably the opposite of Blake's own theological convictions. Urizen, believing that Orc is connected to chaos, seeks predictability and order. He seeks to do so by creating laws which enslave humankind. Urizen crucifies Orc, in the form of a serpent, and war spreads over the land.[16]

In The Four Zoas this is overridden: there the parents produce the four sons Rintrah, Palamabron, Bromion and Theotormon. This is a double-dialectical analysis, rather than an inconsistency as such.

On the other hand Orc is connected to Luvah in The Four Zoas VIII.

Notes

- ↑ Damon 1988 p. 309

- ↑ Morris Eaves, Robert N. Essick, and Joseph Viscomi (eds.). "Notes on "Europe a Prophecy, copy B, object 2 (Bentley 2, Erdman ii, Keynes ii)"". William Blake Archive. Retrieved January 31, 2014.

- ↑ Morris Eaves, Robert N. Essick, and Joseph Viscomi (eds.). "Europe a Prophecy, copy B, object 2 (Bentley 2, Erdman ii, Keynes ii)". William Blake Archive. Retrieved January 31, 2014.

- ↑ Damon 1988 pp. 309–310

- ↑ Frye 1990 pp. 209–211

- ↑ Frye 1990 pp. 214–215, 220

- ↑ Frye 1990 pp. 218–219

- ↑ Morris Eaves, Robert N. Essick, and Joseph Viscomi (eds.). "Notes on:A Large Book of Designs, copy A, object 2 (Bentley 85.2, Butlin 262.3)". William Blake Archive. Retrieved January 13, 2014.

- ↑ Morris Eaves, Robert N. Essick, and Joseph Viscomi (eds.). "A Large Book of Designs, copy A, object 2 (Bentley 85.2, Butlin 262.3)". William Blake Archive. Retrieved January 13, 2014.

- ↑ Bentley 2003 pp. 138–139

- ↑ Bentley 2003 pp. 151–152

- ↑ Bentley 2003 pp. 155

- ↑ Bentley 2003 p. 160

- ↑ Frye 1990 p. 213

- ↑ Bentley 2003 p. 271

- ↑ Frye 1990 pp. 221–223

References

- Bentley, G. E. (Jr). The Stranger From Paradise. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003.

- Damon, S. Foster. A Blake Dictionary. Hanover: University Press of New England, 1988.

- Frye, Northrop. Fearful Symmetry. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990.