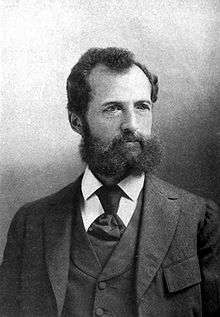

Ottmar Mergenthaler

| Ottmar Mergenthaler | |

|---|---|

Ottmar Mergenthaler | |

| Born |

11 May 1854 Hachtel |

| Died |

28 October 1899 (aged 45) Baltimore |

| Cause of death | Tuberculosis |

| Nationality | Naturalized German-American |

| Occupation | Inventor |

| Known for | Linotype |

| Height | 5'9" |

| Awards |

Elliott Cresson Medal (1889) John Scott Medal (1891) |

Ottmar Mergenthaler (May 11, 1854 – October 28, 1899) was a German-born inventor who has been called a second Gutenberg, as Mergenthaler invented the linotype machine, the first device that could easily and quickly set complete lines of type for use in printing presses. This machine revolutionized the art of printing.

Life and career

Mergenthaler was born in Hachtel, Württemberg, Germany. He was the third son of a school teacher, Johann Georg Mergenthaler, from Hohenacker near the city of Waiblingen.[1]

He was apprenticed to a watchmaker in Bietigheim before emigrating to the United States in 1872 to work with his cousin August Hahl in Washington, D.C. Mergenthaler eventually moved with Hahl's shop to Baltimore, MD. In 1881, Mergenthaler became Hahl's business partner.[2]

In 1876 he was approached by James O. Clephane, who sought a quicker way of publishing legal briefs,[3] via Charles T. Moore, who held a patent on a typewriter for newspapers which did not work and asked Mergenthaler to construct a better model. Mergenthaler recognized that Moore's design was faulty and two years later he assembled a machine that stamped letters and words on cardboard. Although a fire destroyed all his designs and models, he started to work on the invention again as he wrote to himself "more books — more education for all. At home we had no money for school books..."

He found a supporter in Whitelaw Reid of the New York Tribune. Another fifty patents were required before Mergenthaler could show a more or less usable model to the New York Tribune on July 3, 1886. While he was riding on a train, the idea came to him: why a separate machine for casting and another for stamping? Why not stamp the letters and immediately cast them in metal in the same machine? By 1884 the idea of assembling metallic letter molds, called matrices, and casting molten metal into them, all within a single machine, was applied.[4] Mergenthaler reportedly got the idea for the brass matrices that would serve as molds for the letters from wooden molds used to make "Springerle," which are German Christmas cookies. His first attempt proved the idea feasible, and a new company was formed, then fights with shareholders and unions followed with the press even in Germany attacking him. Finally success came with many honors, including a trip to his old home town.[5]

In the printing office of the New York Tribune the machine was immediately used on the daily paper and a large book. The book, the first ever composed with the new Linotype method was titled The Tribune Book of Open-Air Sports.[6]

Initially, The Mergenthaler Linotype Company was the only company producing linecasting machines, but around 1914 a linecasting machine would be produced by the competition — The Intertype Company — using the same matrices as the Linotype, only where Mergenthaler prided themselves on intricately formed cast-iron parts on their machine, Intertype machined many of their similar parts from steel and aluminum.

During the 1970s and 1980s, linotype and similar "hot metal" typesetting machines were retired and replaced with phototypesetting equipment and later computerized typesetting and page composition systems.

Today most operating linotype machines can be found in newspaper museums, producing printing slugs for use together with handset type. However, The Saguache Crescent and its publisher Ray Coombs still use a linotype machine to produce a weekly newspaper much as it has for 134 years.[7]

In 1878, Mergenthaler became a naturalized citizen of the United States. He died of tuberculosis in Baltimore in 1899.

Legacy

An operational Linotype machine is on display at the Baltimore Museum of Industry, in the museum's print shop. Baltimore's vocational high school, Mergenthaler Vocational Technical Senior High School, which opened in 1953, is named after him, although it is commonly referred to simply as "MERVO".

Mergenthaler Hall on the Homewood Campus of the Johns Hopkins University was constructed in 1940–41 with donations by Eugene and Mrs. Ottmar Mergenthaler, son and widow of Ottmar Mergenthaler.

See also

References

- ↑ Kahan, Basil (1999), Ottmar Mergenthaler: The Man and his Machine : A Biographical Appreciation of the Inventor on His Centennial, New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll, ISBN 1-58456-007-X.

- ↑ Tsaniou, Styliani. "Ottmar Mergenthaler." In Immigrant Entrepreneurship: German-American Business Biographies, 1720 to the Present, vol. 3, edited by Giles R. Hoyt. German Historical Institute. Last modified July 26, 2013.

- ↑ "Linotype at 50". Time. July 13, 1936. Retrieved 2009-01-07.

- ↑ The World Book Encyclopedia, 1972.

- ↑ Hutchins, Olga (2011-11-30). "Ottmar Mergenthaler". Baltimore: Zion Lutheran Church of the City of Baltimore.

- ↑ Nelson, Randy F (1981), The Almanac of American Letters, Los Altos, CA: William Kaufmann, p. 286, ISBN 0-86576-008-X.

- ↑ Deam, Jenny (August 13, 2013), The Los Angeles Times, p. A13.

External links

- Baltimore History Site

- Linotype – Chronik eines Firmennamens [Linotype – Chronologie of a Company Name]: ebook on the Linotype machine

- Overview of Mergenthaler's life

- Ottmar Mergenthaler at Find a Grave

- Iles, George (1912), Leading American Inventors, New York: Henry Holt & Co, pp. 393–432

- Ottmar Mergenthaler at 159 West Lanvale Street - Explore Baltimore Heritage