Oval track racing

Oval track racing is a form of closed-circuit automobile racing that is contested on an oval-shaped track. An oval track differs from a road course in that the layout resembles an oval with turns in only one direction, almost universally left (counter-clockwise orientation). Oval tracks are dedicated motorsport circuits, used predominantly in North America. They often have banked turns and some, despite the name, are not precisely oval, and can have unique variances in shape.

Oval track racing is the predominant form of auto racing in the United States. According to the 2013 National Speedway Directory, the total number of oval tracks, drag strips and road courses in the United States is 1,262, with 901 of those being oval tracks and 683 of those being dirt tracks. Major forms of oval track racing include stock car racing, open-wheel racing, sprint car racing, modified car racing, midget car racing and dirt track motorcycles.

Among the most famous oval tracks in North America are the Indianapolis Motor Speedway and Daytona International Speedway. Notable ovals in other countries include Rafaela in Argentina, Motegi in Japan, Lausitzring in Germany, the Calder Park Thunderdome in Australia, Brooklands and Rockingham in the United Kingdom, Monza in Italy, and Montlhéry in France.

Track classification (size)

Oval tracks are classified based upon their size, surface, and shape. Their size can range from only a few hundred feet to over two and a half miles. Track surfaces can be dirt, concrete, asphalt, or a combination of concrete and asphalt. Some ovals in the early twentieth century had wood surfaces.

The definitions used to differentiate track sizes have changed over the years. While some tracks use terms such as "speedway" or "superspeedway" in their name, they may not meet the specific definitions used in this article.

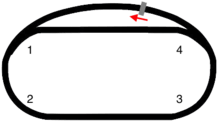

A typical oval track consists of two parallel straights, connected by two 180° turns. Although most ovals generally have only two radii curves, they are usually advertised and labeled as four 90° turns.

Short track

A short track is an oval track less than one mile (1.6 km) long, with the majority being 0.5 miles (0.8 km) or shorter. Drivers seeking careers in oval track racing generally serve their apprenticeship on short tracks before moving up to series which compete on larger tracks. Due to their short length and fast action, these tracks are often nicknamed "bullrings".

Professional-level NASCAR races on short tracks usually utilize a 500-lap or 400-lap distance. Short tracks in many cases have lights installed and routinely host night races.

Mile oval

Synonymous with the name, a 1-mile (1.61 km) oval is a popular and common length for oval track racing. The exact measurements, however, can vary by as much as a tenth of a mile and still fall into that category. Most mile ovals are relatively flat-banked, with Dover being a notable exception.

Intermediate

Also referred to with the general term of "speedway", these courses are 1 to 2 miles (1.6 to 3.2 km) in length, but the term is particularly reserved for 1.5-mile (2.4 km) tracks. Since their size allows them to compromise high speeds with sightlines, they have become commonplace in major racing series that utilize oval tracks. During the race track construction boom of the 1990s, these tracks began to be labeled with the rather derogatory term "cookie cutter" tracks, as their differences were perceived to be minimal. In 1992, Charlotte became the first intermediate track to install lights and allow for night racing. It is now commonplace for these types of tracks to host night races. Intermediate tracks usually have moderate to steep banking.

Superspeedway

A superspeedways is at least 2.0 miles (3.2 km) in length. There are seven superspeedways in the United States, the most famous being Indianapolis Motor Speedway and Daytona International Speedway, both 2.5 miles (4.0 km) long. These tracks were built in 1909 and 1959 respectively. Indianapolis Motor Speedway was built as a facility for the automotive industry to conduct research and development.[1] Daytona International Speedway was built as a replacement for the Daytona Beach Road Course, which combined the town's main street and its famous beach. Daytona hosts the Daytona 500, NASCAR's most prestigious race, while the Indianapolis Motor Speedway is home to the Indianapolis 500 and the Brickyard 400.

The longest superspeedway is the Talladega Superspeedway in Talladega, Alabama. Built in 1969, it is 2.66 miles (4.28 kilometers) long, and holds the current record for fastest speed in a stock car, lapping at an average of 216.309 mph (348.116 km/h) and reaching 228 mph (367 km/h) at the end of the backstretch.[2] Daytona and Talladega are the pinnacle of stock car superspeedway racing, where restrictor plates are mandated by the sport's ruling body to reduce the high speeds accommodated by their steep banking.

Other superspeedways used by NASCAR include the Michigan International Speedway (2.0 miles), Auto Club Speedway (known as California Speedway prior to February 2008) (2.0 miles), and Pocono Raceway (2.5 miles). Auto Club Speedway and Michigan are often considered intermediate tracks due to their similarities with 1.5-mile tracks, while Pocono and Indianapolis are sometimes classified separately, as they are the only long, flat tracks on the schedule. Auto Club Speedway, which joined Indianapolis and Pocono[3] as the one of three superspeedways used in the Verizon IndyCar Series, was the site of Gil de Ferran's qualifying lap of 241.428 mph (388.541 km/h) in the CART FedEx Championship Series in 2000,[4] presently the fastest lap recorded at an official race meeting.[5] Auto Club Speedway was left off the 2016 Indy Car schedule.

The seventh superspeedway is Texas World Speedway, which is the original "sister track" to Michigan. The two-mile oval, with its 22-degree banking, was the site of Mario Andretti's closed-course record of 214.158 mph (344.654 km/h) which stood for 12 years. No major professional series have raced at TWS since the 1990s, however, the track's 1.8, 2.9 and 3.1-mile road courses are very popular with amateur racing clubs.

Track classification (shape)

While many oval tracks conform to the traditional symmetrical design, asymmetrical tracks are not uncommon.

Classical geometric shapes

| Shape | Description | Examples | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short Track | Mile Oval | Intermediate | Superspeedway | ||

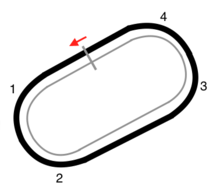

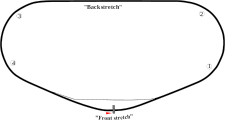

| Paper clip oval | One sub-classification of the traditional oval shape is the "paper clip" oval. The layout consists of two long straights, connected by two sharp, tight-radius turns, giving the track a shape resembling a paper clip. The courses are usually very challenging, and usually offer little banking, making the turns very slow and tight to maneuver. This is the classic layout of short tracks or mile ovals. Most short tracks are paper clips. But there exist some tracks about 1 mile length with this shape, too. | | | | |

| Rounded-off rectangle or square | One prominent, but now uncommon shape is the "rounded-off rectangle". Pursuant to its name, the track shape resembles a rectangle, with two long straights and two short straights, connected by four separate turns. The primary characteristic of a rounded-off rectangle that differentiates it from a traditional oval shape, is the presence of two "short chutes", one between turns one and two, and one between turns three and four. While most traditional ovals have two continuous 180° radii (advertised as four 90° turns), this shape actually has four distinct 90° curves. When it was first constructed, the Homestead-Miami Speedway was designed to this layout and touted as a "mini-Indy." However, at only 1.5 miles (one mile shorter than Indy), the track proved to be uncompetitive, owing largely to the sharp corners, and was soon reconfigured as a traditional oval. Indianapolis remains as the only major track to this specification. Tracks of this shape have been avoided due to grandstand sight line issues, slow corners, and dangerous impact angles. However, numerous private manufacturers' test tracks use this type of layout. The only major short track with a rectangular layout has the shape of a rounded-off square with four nearly identical straights and turns. |  Flemington Speedway, a square | - | Homestead (original design) | Ontario |

| Rounded-off trapezoid | A very rare layout is a trapezoid oval course. The difference to rounded-off rectangle is the shorter back straight and longer front straight. So, the Turns 1 und 4 are tighter than the Turns 2 and 3. | - | - | - | |

| Rounded-off triangle | The classic triangular layout is rare in oval courses, too. Technically, there are tri-ovals. In the strict sense, the modern oval tracks are called tri-oval, which rather are similar to a D. See next section. The Pocono Raceway is a triangular course with three distinct, widely varying turns. Due to its layout the "Pocono Raceway" is often described with the words: "It is an oval course, which drives like a road course." The triangle is a popular oval shape outside the United States. There are some triangular oval tracks in Canada, Germany and Mexico. |  Sanair Super Speedway, a equilateral triangle Concord Speedway | - | ||

Tri-ovals

The tri-oval is the common shape of the ovals from the construction booms of the 1960s and 1990s. The use of the tri-oval shape for automobile racing was conceived by Bill France, Sr. during the planning for Daytona. The triangular layout allowed fans in the grandstands an angular perspective of the cars coming towards and moving away from their vantage point. Traditional ovals (such as Indianapolis) offered only limited linear views of the course, and required fans to look back and forth much like a tennis match. The tri-oval shape prevents fans from having to "lean" to see oncoming cars, and creates more forward sight lines. The modern tri-ovals were often called as cookie cutters because of their (nearly) identical shape and identical kind of races.

| Shape | Description | Examples | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short Track | Mile Oval | Intermediate | Superspeedway | ||

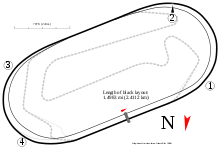

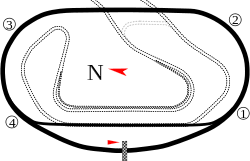

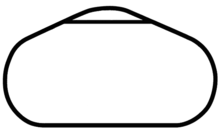

| Tri-oval | A tri-oval resembles an isosceles triangle with rounded-off corners. The circuits typically have a straight backstretch, while the main straightaway where the pit area and most grandstands are located, has a "tri-oval" curve (sometimes characterized as a fifth curve) that makes the mainstretch skewed. Tri-ovals have become preferable to track builders as they offer superior sightlines. Generally on tri-ovals the start-finish line is located on the apex of the tri-oval curve. Two exceptions are Talladega and Walt Disney World Speedway, where the start-finish line are located on the straight between the curve and turn one. | Wisconsin International Raceway |  The Kansas Speedway | | |

| Quad-oval | A tri-oval with a "double dogleg" is often called a "quad-oval". A quad-oval is very similar to a tri-oval in sightlines and layout. One specific feature is that the start-finish line segment actually falls on a straight section, rather than along a curve. The shape has become a signature for Speedway Motorsports, which owns all major quad-ovals in the United States. The Calder Park Thunderdome in Melbourne, Australia, is also an example of a quad-oval speedway, though since its opening in 1987 it has generally been referred to as a tri-oval. | - | | - | |

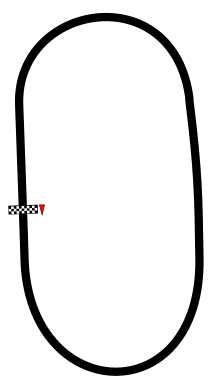

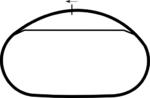

| D-shaped oval | A variation of tri-oval is the "D-shaped oval". Similar to a tri-oval, a D-shaped oval has a straight backstretch, but a long, sweeping frontstretch, giving the circuit a layout resembling the letter D. The shape originated with a pair of sister tracks built in the 1960s: Michigan International Speedway and Texas World Speedway. Initially, this design has been used only for superspeedways. But there are now some short tracks with this shape, too. | | | - | |

Unique shapes

There are a lot of oval tracks, which neither have a classical geometric shape nor still represent a modern tri-oval in the strict sense. While these courses still technically fall under the category of ovals, their unique shape, flat corners, hard braking zones, or increased difficulty, often produces driving characteristics similar to those of a road course.

| Shape | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Egg-shape | There are some tracks, which were planned as a classic ovals, but had to be built for reasons of space in egg shape. An egg-shaped oval substantially corresponds to the classical form, however, the two straights are non-parallel arranged. A straight line is slightly longer than the other and the two curves have different radii. | |

| Dogleg | Some oval tracks have minor variations, such as kinks or doglegs. A "dogleg" is a defined as a soft curve down one of the straights, either inward or outward, which skews the oval into a non-symmetric or non-traditional shape. While the extra curve would seemingly give the oval five turns, the dogleg is normally omitted from identification, and the ovals are still labeled with four turns. | |

| Kidney-bean-shape | A Kidney-bean-shape had a unique right-hand dogleg. Apart from that the track is largely classical or Egg shaped. | |

Concentric oval track / legends oval

Some facilities feature several ovals track of different sizes, often sharing part of the same front straightaway. The now defunct Ascot Speedway featured 1/2 mile and 1/4 mile dirt oval tracks, and Irwindale Speedway features 1/2 mile and 1/3 mile concentric paved oval tracks. Pocono Raceway once had a 3/4 mile oval which connected to the mainstrech, and circled around the garage area.

In 1991, Charlotte Motor Speedway connected the quad oval start-finish straight to the pit lane with two 180 degree turns, resulting in a concentric 1/4-mile oval layout. The 1/4-mile layout became a popular venue for legends car racing. The name "legends oval" was derived from this use. They have also seen use with go-karts, short track stock cars, and other lower disciplines. This idea was adopted by numerous tracks including Texas Motor Speedway, Atlanta Motor Speedway, Kentucky Speedway, Las Vegas Motor Speedway, and Iowa Speedway which has a 1/8 mile version.

Perhaps the most unusual concentric oval facility is Dover Speedway-Dover Downs. The one-mile oval track encompasses a 0.625-mile harness racing track inside.

Track classification (banking)

Oval tracks usually have slope in both straight and in curves, but the slope on the straights is less, circuits without any slope are rare to find, low-slope are usually old or small tracks, high gradient are more common in new circuits.

Circuits like Milwaukee Mile and Indianapolis Motor Speedway are approximately 9° tilt in curves are considered low slope, superspeedways like Talladega has up to 33° tilt in curves, Daytona has up to 32°, both are considered high inclination. Charlotte and Dover are the intermediate with the highest bank, 24° tilt. Bristol is the short oval with up to 36° (later cut to 26° to 28°).

Comparison banking and size

Combined road course

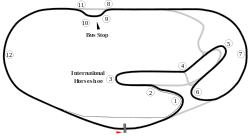

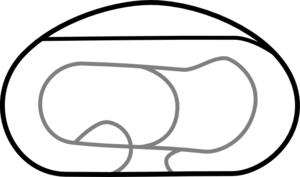

_track_map--Combined_road_and_Thunderdome_(oval)_course.svg.png)

A "Combined road course" is an oval track racing facility that features a road course in the infield (or outfield), that is usually linked to the oval circuit. This type of course allows the facility to be used for road racing. A typical combined road course consists of the oval portion of the track, utilizing the same start/finish line, and same pit area, but a mid-course diversion to a winding road circuit in the infield (or outfield). At some point, the circuit leads back to the main oval, and completes the rest of the lap. On some of the faster ovals, a chicane is present on long back-straights, to keep speeds down, and create additional braking/passing zones. Some more complex facilities feature a stand-alone road course layout(s) in the infield not directly linked to the oval layout, or otherwise utilizing only a short portion of the oval.

Combined road courses combine the high speed characteristics of ovals with the technical precision of road courses. It allows road racing disciplines the unique experience of being held in the stadium style atmosphere of an oval superspeedway. Numerous combined road courses saw widespread use with sports cars in the 1970s and early 1980s. However, their use has since diminished considerably, since most layouts lacked the desirable topography and competitive challenges of natural road courses. In addition, most combined road course circuits offer poor sightlines for fans sitting in the grandstands. Oftentimes the challenging infield portion is obscured or not visible at all from the grandstands that line the circumference of the oval track, so many fans choose to view from the ground level inside the infield - leaving the grandstands mostly empty and unsightly.

Many combined road course layouts have been abandoned, or are only used for testing and amateur race meets. Since 1962, the most famous race continuously held on a combined road course has been the 24 Hours of Daytona.

In some rare examples, the combined road course layout is run in the opposite direction as the oval circuit. For instance, at Indianapolis the oval is run counter-clockwise, but the combined road course used during the Grand Prix is run clockwise. However the Moto GP races were run counter-clockwise, with some reconfigured corners to fix corner apex problems. Michigan was also an example of a clockwise combined road course. Another example is the Adelaide International Raceway in Australia which combines a 2.41 km (1.50 mi) road course with an 0.805 km (0.500 mi) speedway bowl. The Bowl forms a permanent part of the road course and also runs clockwise. At many tracks, multiple configurations are available for the combined road course layout(s).

An example of an outfield combined road course can be seen at the Calder Park Raceway in Melbourne, Australia. The Calder Park complex has a 1.119 mi (1.801 km) high-banked oval speedway called the Thunderdome as well as a separate road course. The road course and the oval can be linked via two short roads that connect the front straight of the road course to the back straight of the oval. As they are separate tracks, this creates a unique situation where different races can actually be run on both the oval and the full road course at the same time. Also unique is that unlike most combined circuits which utilise the oval track's start/finish line and pits, in the case of Calder Park it is the road course start/finish line and pits that are used. Unfortunately this configuration was only used twice (both in 1987) and has not been used for major motor racing since hosting Round 9 of the 1987 World Touring Car Championship.

Oval racing

Pack racing

Pack racing is a phenomenon found on fast, high-banked superspeedways. It occurs when the vehicles racing are cornering at their limit of aerodynamic drag, but within their limit of traction. This allows drivers to race around the track constantly at wide open throttle. Since the vehicles are within their limit of traction, drafting through corners will not hinder a vehicle's performance. As cars running together are faster than cars running individually, all cars in the field will draft each other simultaneously in one large pack. In stock car racing this is often referred to as "restrictor plate racing" because NASCAR mandates that each car on its two longest high-banked ovals, Talladega and Daytona, use an air restrictor to reduce horsepower.

The results of pack racing may vary. As drivers are forced to race in a confined space, overtaking is very common as vehicles may travel two and three abreast. This forces drivers to use strong mental discipline in negotiating traffic. There are drawbacks, however. Should an accident occur at the front of the pack, the results could block the track in a short amount of time. This leaves drivers at the back of the pack with little time to react and little room to maneuver. The results are often catastrophic as numerous cars may be destroyed in a single accident. This type of accident is often called "The Big One".[6]

Comparison with road racing

Oval track racing requires different tactics than road racing. While the driver doesn't have to shift gears nearly as frequently, brake as heavily or as often, or deal with turns of various radii in both directions as in road racing, drivers are still challenged by negotiating the track. Where there is generally one preferred line around a road course, there are many different lines which can work on an oval track. The preferred line depends on many factors including track conditions, car set-up, and traffic. The oval track driver must choose which line to use each time he approaches a corner. On a short track in a 25 lap feature race, a driver might not run any two laps with the same line. Both types of racing place physical demands on the driver. A driver in an IndyCar race at Richmond International Raceway may be subject to as many lateral g-forces (albeit in only one direction) as a Formula One driver at Istanbul Park.

Weather also plays a different role in each discipline. Road racing offers a variety of fast and slow corners that allow the use of rain tires. Paved oval tracks generally don't run with a wet track surface. Dirt ovals will sometimes support a light rain. Some tracks (e.g., Evergreen Speedway in Monroe, WA) have "rain or shine" rules requiring races to be run in rain.

Safety has also been a point of difference between the two. While a road course usually has abundant run-off areas, gravel traps, and tire barriers, oval tracks usually have a concrete retaining wall separating the track from the fans. Innovations have been made to change this, however. The SAFER barrier was created to provide a less dangerous alternative to a traditional concrete wall. The barrier can be retrofitted onto an existing wall or may take the place of a concrete wall completely.

Oval track construction booms

There have been two distinct oval race track construction "booms" in the United States. The first took place in the 1960s, and the second took place in the mid-to-late 1990s. The majority of tracks from the 1960s boom and the 1990s boom have survived, but some tracks failed to achieve long term financial success. Incidentally, these two booms loosely coincided with the similar construction boom of the baseball/football cookie-cutter stadiums of the 1960s and 1970s, and the subsequent sport-specific stadium construction boom that began in the 1990s.

Tracks built during the 1960s boom

- Daytona International Speedway (1959)

- Charlotte Motor Speedway (1960)

- Atlanta Motor Speedway (1960)

- North Carolina Motor Speedway (1965; demoted to primarily a test facility since 2005)

- Dover International Speedway (1966)

- Michigan International Speedway (1968)

- Texas World Speedway (1969; hosting primarily amateur racing and testing since 1981)

- Talladega Superspeedway (1969)

- Ontario Motor Speedway (1970; demolished 1980)

- Pocono Raceway (1971)

Tracks built during the 1990s boom

- Homestead-Miami Speedway (1995)

- Walt Disney World Speedway (1996; demolished 2015–2016)

- Las Vegas Motor Speedway (1996)

- Texas Motor Speedway (1996)

- Gateway International Raceway (1997)

- Pikes Peak International Raceway (1997; hosting only non-major events since 2008)

- Auto Club Speedway (1997)

- Memphis International Raceway (1998)

- Chicago Motor Speedway (1999; demolished in 2009)

- Kentucky Speedway (2000)

- Kansas Speedway (2001)

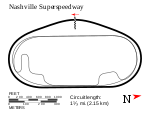

- Nashville Superspeedway (2001; closed 2011)

- Chicagoland Speedway (2001)

See also

References

- ↑ Indystar.com"History of the Indianapolis 500" Retrieved November 19, 2007

- ↑ NASCAR.com – Rusty Wallace hits 228 mph (367 km/h) in Talladega trial – June 10, 2004

- ↑ "IndyCar returns to Pocono for 1st time since 1989". Sports Illustrated. April 10, 2013. Retrieved April 11, 2013.

- ↑ "De Ferran wins pole, sets record". Las Vegas Sun. October 28, 2000. Archived from the original on November 10, 2013.

- ↑ Webster, George. "PRN — Performance Racing News — Who holds the world's closed course record? A.J. Foyt | PRN — Performance Racing News". Prnmag.com. Retrieved February 22, 2012.

- ↑ CNNSI"Hangin' Back" retrieved November 17, 2007

.svg.png)

_map.svg.png)

_track_map--Thunderdome_Speedway.svg.png)

_-_Speedway.svg.png)