Paris in the Belle Époque

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Paris |

|

| See also |

|

|

Paris in the Belle Époque, between 1871 and 1914, from the beginning of the Third French Republic until the First World War, saw the construction of the Eiffel Tower, the Paris Métro, the completion of the Paris Opera, and the beginning of the Basilica of Sacré-Cœur on Montmartre. Three universal expositions in 1878, 1889 and 1900 brought millions of visitors to Paris to see the latest in commerce, art and technology. Paris was the scene of the first public projection of a motion picture, and the birthplace of the Ballets Russes, Impressionism and Modern Art.

The expression Belle Époque came into use after the First World War, a nostalgic term for what seemed a simpler time of optimism, elegance and progress.

Rebuilding after the Commune

After the violent end of the Paris Commune in May 1871, the city was governed by martial law, under the strict surveillance of the national government. The government and parliament did not return to the city from Versailles until 1879, though the Senate returned earlier to its home in the Luxembourg Palace.[1]

The end of the Commune also left the city's population deeply divided. Gustave Flaubert described the atmosphere in the city in early June 1871: "One half of the population of Paris wants to strangle the other half, and the other half has the same idea; you can read it in the eyes of people passing by." [2] But that sentiment soon became secondary to the need to reconstruct the buildings that had been destroyed in the last days of the Commune. The Communards had burned the Hôtel de Ville (including all the city archives), the Tuileries Palace, the Palais de Justice, the Prefecture of Police, the Ministry of Finances, the Cour des Comptes, the State Council building at the Palais-Royal, and many others. Several streets, particularly the rue de Rivoli, had also been badly damaged by the fighting. The column in Place Vendôme had been toppled, on a suggestion from Gustave Courbet, a supporter of the Commune. On top of the reconstruction, the new government was obliged to pay 210 million francs in gold to the victorious German Empire as reparations for the disastrous Franco-Prussian War of 1870. On August 4, 1871, at the first meeting of the city council after the Commune, the new Prefect of the Seine, Léon Say, put forward a plan to borrow 350 million francs for reconstruction and to pay Germany. The city's bankers and businessmen quickly raised the money, and the reconstruction was soon underway.

The Conseil d'État and Palais de la Légion d'Honneur (Hôtel de Salm) were rebuilt in their original style. The new Hôtel de Ville was given a more picturesque Renaissance style than the original, borrowed from the Château de Chambord in the Loire Valley, with a façade decorated with statues of outstanding personages who contributed to the history and fame of Paris. The destroyed Ministry of Finance on the rue de Rivoli was replaced by a grand hotel, while the Ministry moved into the Richelieu wing of the Louvre, where it remained until 1989. The ruined Cour des Comptes on the left bank was replaced by the gare d'Orléans, also known under the name gare d'Orsay, now the Museé d'Orsay. The one difficult decision was the Tuileries Palace; built in the 16th century by Marie de' Medici, a royal and imperial residence. The interior had been entirely destroyed by the fire, but the walls were still largely intact, and remained standing for ten years, while the fate of the ruins was debated. Baron Haussmann, in retirement, appealed for a restoration of the building as an historic monument, and it was proposed to turn it into a new museum of modern art. But, in 1881, the new Chamber of Deputies, more sympathetic to the Commune than previous governments, decided that it was too much a symbol of the monarchy, and had the walls pulled down.[3]

-

Walls of the Tuileries Palace

-

The Ministry of Finance on rue de Rivoli

-

Remains of the column in Place Vendôme

-

Rue Royale and the church of the Madeleine

-

Rue de Rivoli

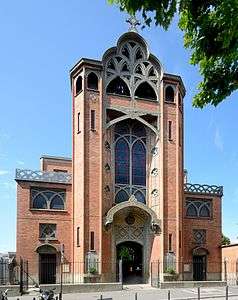

On 23 July 1873, the National Assembly endorsed the project of building a basilica at the site where the uprising of the Paris Commune had begun; it was intended to atone for the sufferings of Paris during the Franco-Prussian War and the Commune. The Basilica of Sacré-Cœur was built in the neo-Byzantine style, and paid for by public subscription. It was not finished until 1919, and quickly became one of the most recognizable landmarks in Paris.[4]

The Parisians

The population of Paris was 1,851,792 in 1872, at the beginning the Belle Époque. By 1911, it reached 2,888,107, higher than today's (2015) population. At the end of the Second Empire and the beginning of the Belle Époque, between 1866 and 1872, the population of Paris grew only 1.5 percent. The population surged by 14.09 percent between 1876 and 1881, then slowed down again to 3.3 percent between 1881 and 1886. After that it grew very slowly until the end of the Belle Époque, reaching its historic high of almost three million persons in 1921, before beginning a long decline until the early 21st century.[5]

In 1886, about one-third of the population of Paris (35.7 percent) had been born in Paris. More than half 56.3 percent) had been born in other departments of France, and about eight-percent outside France.[6] In 1891, Paris was the most cosmopolitan of European capital cities, with seventy-five foreign-born residents for every thousand inhabitants, compared with twenty-four for Saint-Petersburg, twenty-two for London and Vienna, and eleven for Berlin. The largest communities of immigrants were Belgians, Germans, Italians and Swiss, with between twenty and twenty-eight thousand persons from each country, followed by about ten thousand from Great Britain and equal number from Russia; eight thousand from Luxembourg; six thousand South Americans; and five thousand Austrians. There were 445 Africans, 439 Danes, 328 Portuguese and 298 Norwegians. Certain nationalities were concentrated in specific professions; Italians in the businesses of making ceramics, shoes, sugar and conserves; Germans in leather-working, brewing, baking and charcuterie. The Swiss and Germans were predominant in businesses making watches and clocks, and also accounted for a large proportion of the domestic servants.[7]

The remnants of old Paris aristocracy and the new aristocracy of bankers, financiers and entrepreneurs mostly had their residences in the 8th arrondissement, from the Champs-Élysées to the Madeleine), in the quartier de l'Europe and butte Chaillot; the Faubourg Saint-Honoré, the quartier Saint-Georges, from rue Vivienne and the Palais-Royal to Roule and the plain of Monceau. On the right bank, they lived in Le Marais; on the left bank, on the south of the Latin quarter, at N(Notre-Dame-des-Champs and Odéon; near Les Invalides and at the École Militaire. The less affluent shop owners lived from porte Saint-Denis to Les Halles, to the west of boulevard de Sébastopol. The middle class employees of enterprises, small businesses and government lived closer to the center, along the Grands boulevards, in the 10th arrondissement, in the 1st and 2nd arrondissements near the Bourse (Stock Exchange), in the Sentier quarter near Les Halles, and in Le Marais.[8]

Under Napoleon III, Haussmann had demolished the poorest, most crowded and historical neighborhoods in the center of the city to make room for the new boulevards and squares. The working-class Parisians had moved out of the center toward the edges of the city; particularly to Belleville and Ménilmontant in the east, to Clignancourt and Grandes Carrières to the north, and on the left bank to the area around the Gare d'Austerlitz, Javel and Grenelle, usually to neighborhoods that were close to their places of work. Small quarters of working-class Parisians still remained in the center of the city, on the sides of the Montagne Sainte-Geneviève in the Latin Quarter, near the Sorbonne and the Jardin des Plantes, and along the covered Bièvre River, where the tanneries had been located for centuries.[9]

Paris was both the richest and poorest city in France. Twenty-four percent of the wealth in France was found in the Seine department, but fifty-five percent of burials of Parisians were made in the section for those unable to pay. In 1878, two-thirds of Parisians paid less than 300 francs a year for their lodging, a very small amount at the time. An 1882 study of Parisians, based on funeral costs, concluded that twenty-seven percent of Parisians were upper or middle class, while seventy-three percent were poor or indigent. Incomes varied greatly according to the neighborhood: in the 8th arrondissement, there were eight poor persons for ten upper or middle class residents; in the 13th, 19th and 20th arrondissements, there were seven or eight poor for every well-off resident. [10]

The Apaches of Paris

Apaches was a term that was introduced by Paris newspapers in 1902 for young Parisians who engaged in petty crime and sometimes fought each other or the police. They usually lived in Belleville and Charonne. Their activities were described in lurid terms by the popular press, and they were blamed for all varieties of crime in the city. In September 1907, the newspaper Le Gaulois described an Apache as "the man who lives on the margin of society, ready to do anything, except to take a regular job, the miserable who breaks in a doorway, or stabs a passer-by for nothing, just for pleasure.[11]

Government and politics

The French national government concluded, after the Commune, that Paris was too important to be run by the Parisians alone; on April 14, 1871, just before the end of the Commune, the National Assembly, meeting in Versailles, passed a new law giving Paris a special status different from other French cities, and subordinate to the national government. All male Parisians could vote. The city was given a municipal council of eighty members, four from each arrondissement, for a term of three years. The council could meet for four sessions a year, none longer than ten days, except when considering the budget, when six weeks were allowed. There was no elected mayor. The real powers in the city remained the Prefect of the Seine and the Prefect of Police, both appointed by the national government.[12]

The first legislative elections after the Commune, on January 7, 1872, were won by the conservative candidates; Victor Hugo, running as an independent candidate on the side of the radical republicans, was soundly defeated.[13] However, the radical Republicans dominated the Paris municipal elections of 1878, winning 75 of the 80 municipal council seats. In 1879, they changed the name of many of the Paris streets and squares; Place du Château-d’Eau became Place de la République, and a statue of the Republic was placed in the center in 1883. The avenues de la Reine-Hortense, Joséphine and Roi-de-Rome were renamed Hoche, Marceau and Kléber, after generals of Napoleon I.

The burning of the Tuileries Palace by the Commune meant there was no longer a residence for the French head of state. The Élysée Palace was chosen as the new residence in 1873. It had been built between 1718 and 1722 by the architect Armand-Claude Mollet for Louis Henri de La Tour d'Auvergne, comte d'Évreux, then had been purchased in 1753 by Lous XV for his mistress, the Marquise de Pompadour. During the Consulate, it was owned by Joachim Murat, one of Napoleon's marshals. In 1805, Napoleon made it one of his imperial residences, and it became the official presidential residence when his nephew, Louis-Napoléon, future emperor, became President of the Second Republic, and remained so to this day. During the Bourbon Restoration the Élysée gardens were a popular amusement park. The Élysée palace had no large room for ceremonial events, so a large ballroom was added during Third Republic.

The most memorable Parisian civic event during the period was the funeral of Victor Hugo in 1885. Hundreds of thousands of Parisians lined the Champs Élysées to see the passage of his coffin. The Arc de Triomphe was draped in black. The remains of the writer were placed in the Panthéon, formerly the Church of Saint-Geneviève, which had been turned into a mausoleum for great Frenchmen during the Revolution of 1789, then turned back into a church in April 1816, during the Bourbon Restoration. After several changes during the 19th century, it was secularized again in 1885 on the occasion of Victor Hugo's funeral.[14]

Social unrest, anarchists and the Boulanger crisis

The Belle Époque was spared the violent uprisings which had brought down two French regimes in the 19th century, but it had its share of political and social conflict and occasional violence. Labor unions and strikes had been legalized during the regime of Napoleon III. The first labor union congress in Paris took place in October 1876,[15] and the socialist party had recruited many members among the Paris workers. On May 1, 1890, the socialists organized the first and unauthorized celebration of May Day, the international day of labor, leading to confrontations between police and demonstrators.

The majority of political violence came from the anarchist movement of the 1890s. The first attack was organized by an anarchist named Ravachol who set off bombs at three residences of wealthy Parisians. On April 25, he set off a bomb at the restaurant Véry at the Palais-Royal, and was arrested. On November 8, anarchists planted a bomb in the office of the Compagnie Minière et Métallurgique, a mining company, on the Avenue de l'Opéra. The police found the bomb, but when it was taken to the police headquarters it exploded, killing six persons. On December 6, an anarchist named Auguste Vaillant set off a bomb in the building of the National Assembly, wounding forty-six persons. On February 12, 1894, an anarchist named Émile Henry set off a bomb at the café of the Hôtel Terminus next to the Gare Saint-Lazare, killing one person and wounding seventy-nine.[16]

Another political crisis shook Paris beginning on December 2, 1887, when the President of the Republic, Jules Grévy, was forced to resign when it was discovered that he had been selling the nation's highest award, the Légion d'honneur. A popular general, Georges Ernest Boulanger, had his name put forward as a potential new leader. He became known as "the man on horseback" because of images of him on his black horse. He was supported by ardent nationalists, who wanted a war with Germany to take back Alsace and Lorraine, lost in the 1870 Franco-Prussian War. Monarchist politicians began to promote Boulanger as a potential new leader, who could dissolve the parliament, become President, bring back the lost provinces and restore the French monarchy. Boulanger was elected to parliament in 1888, and his followers urged him to go to the Élysée Palace and declare himself president; but he refused, saying that he could win the office legally in a few months. The wave of enthusiasm for Boulanger quickly faded away, he went into voluntary exile, and the government of the Third Republic remained firmly in place.[17]

The Police

The Paris police force was completely re-organized after the fall of Napoleon III and the Commune; the sergents de ville were replaced by the 'Gardiens de la paix publique (Guardians of the Public Peace), which by June 1871 had 7,756 men, under the authority of the Prefect of Police, named by the national government. Following a series of anarchist bombings in 1892, the number was increased to 7,000 guardians, 950 sous-brigadiers and 80 brigadiers. In 1901, under the prefect Louis Lépine, in order to keep up with the technology of the time, a unit of policemen on bicycles (called the hirondelles after the brand of the bicycles), was formed, numbering 18 per arrondissement, and reaching 600 by 1906 for the whole city. A unit of river police, the Brigade fluviale, was organized in 1900 for the Universal Exposition, as well as a unit of traffic police, who wore a symbol of a Roman chariot embroidered on the sleeve of their uniform. The first six motorcycle policemen appeared on the streets in 1906.[18]

In addition to the Gardiens de la paix publique (Gardiens de la paix, for short), Paris was guarded by the Garde républicaine (Republican Guard), under the military command of the Gendarmerie nationale. Gendarmes had been a particular target of the Commune; 33 had been taken hostages and were executed by a (Communard) firing squad on rue Haxo on May 23, 1871, in the last days of the Commune. In June 1871, they provided security in the damaged city. They numbered 6,500 men in two regiments, plus a unit of cavalry and a dozen cannon. The number was reduced in 1873 to 4,000 men in a single regiment, called the Légion de la Garde républicaine (Legion of the Republican Guard), with its headquarters on the quai de Bourbon, and the troops quartered in several barracks around the city. The Republican Guard was given the duty of providing security for the President of the Republic at the Élysée Palace, the National Assembly and the Senate, at the prefecture of police, and also at the Opéra, theaters, public balls, racetracks, and other public places. A unit of bicyclists was formed on June 6, 1907. When World War I began, the entire unit of Paris gendarmes was mobilized and fought at the front during war; 222 of them lost their lives. [19]

By a decree of 29 June 1912, to assure the sûreté (security) of Paris by fighting organized crime (Apaches, bande à Bonnot), a criminal section called the Brigade criminelle was created.[20]

Religion

Paris in the Belle Époque saw a long and sometimes bitter dispute between the Catholic Church and governments of the Third Republic. During the Commune, the Church had been particularly targeted for attack; 24 priests and the Archbishop of Paris had been taken hostages and were shot by firing squads in the final days of the Commune. The new government after 1871 was conservative and Catholic, and, through the Ministère des Cultes, provided substantial funding for the Church establishment, and approved the building (without government funds) of the Basilica of Sacré-Cœur on Montmartre as an act of expiation for the events of 1870-1871. The anti-clerical Republicans took power in 1879, and one of their leaders, Jules Ferry, declared: "My objective is to organize humanity without God and without kings." [21] In March 1880, the Assembly outlawed religious congregations not authorized by the State, and on 30 June had the police expel the Jesuits from their building at 33 rue de Sèvres. 260 monasteries and convents were closed in Paris and the rest of France. A new law was passed declaring that all public education should be non-religious (laïque) and obligatory. In 1883, new laws were passed forbidding public prayers, and forbidding soldiers to attend religious services in uniform. In 1881, twenty-seven cadets from the École spéciale militaire de Saint-Cyr (Military Academy of Saint-Cyr) were expelled for attending a mass at church of Saint-Germain-des-Prés. The law against working on Sunday was repealed in 1880 (it was reinstated in 1906 to assure workers a day of rest), and in 1885 divorce was authorized.

The new Municipal Council of Paris, also dominated by radical republicans, had little formal power, but it took many symbolic measures against the Church. Nuns and other religious figures were forbidden to have official positions in hospitals, statues were put up to honor Voltaire and Diderot, and the Panthéon was secularized in 1885 to receive the remains of Victor Hugo. Several of the streets of Paris were renamed for republican and socialist heroes, including Auguste Comte (1885), François-Vincent Raspail (1887 ); Armand Barbès (1882); and Louis Blanc (1885). Specifically forbidden by the Catholic Church, cremation was authorized at the Père Lachaise cemetery. In 1899, the Dreyfus Affair divided Parisians (and the whole of France) even more; the Catholic newspaper La Croix published virulent anti-Semitic articles against the army officer.[22]

The new National Assembly of 1901 had a strongly anti-clerical majority. At the urging of the socialist members, the Assembly officially voted the separation of Church and State on December 9, 1905. The budget of 35 million francs a year given to the Church was cut off, and disputes took place over the official residences of the clergy. On December 17, the police evicted the Archbishop of Paris from his official residence at 127 rue de Grenelle; the Church responded by banning midnight masses in the city. A law of 1907 finally resolved the issue of property; churches built before that date, including the cathedral of Notre Dame, became the property of the French state, while the Catholic Church was given the right to use them for religious purposes. Despite the cutoff of government assistance, the Catholic Church was able to build 24 new churches, including 15 in the suburbs of Paris between 1906 and 1914. Official relations between Church and State were almost non-existent to the end of the Belle Époque.[23]

The Jewish community in Paris had grown from 500 in 1789, or one percent of the Jewish community in France, to 30,000 in 1869, or 40 percent. Beginning in 1881, there were new waves of immigration from Eastern Europe, bringing 7 to 9,000 new arrivals each year, and French-born Jews in the 3rd and 4th arrondissements were soon outnumbered by new arrivals, whose numbers increased from 16 percent of the population in those arrondissements to 61 percent. The pogroms in the Russian Empire between 1905 and 1914 provoked a new wave of immigrants arriving in Paris. The community faced a strong current of antisemitism, exemplified by the Dreyfus Affair. With the arrival of the great number of Ashkenazi Jews from Eastern Europe and Russia, the Paris community became more and more secular and less religious.[24]

There was no mosque in Paris until after the First World War. In 1920, the National Assembly voted to honor the memory of the estimated one hundred thousand Muslims from the French colonies in the Maghreb and black Africa who died for France during the war, and gave a credit of 500,000 francs to build the Grand Mosque of Paris.[25]

The Economy

The economy of Paris suffered an economic crisis in the early 1870s, followed by a long, slow recovery; then a period of rapid growth beginning in 1895 until the First World War. Between 1872 and 1895, in the capital, 139 large enterprises closed their doors, particularly textile and furniture factories, those in the metallurgy sector, and printing houses, four industries which for sixty years had been the major employers in the city. Most of these enterprises had employed, each, between 100 and 200 workers. Half of the large enterprises on the center of the city's right bank moved out, in part because of the high cost of real estate, and also to get better access to transportation on the river and railroads. Several moved to less-expensive areas at the edges of the city, around Monparnasse and La Salpêtriére, while others went to the 18th arrondissement, La Villette and the Canal Saint-Denis, to be closer to the river ports and the new railroad freight yards, to Picpus and Charonne in the southeast, or near Grenelle and Javel in the southwest. The total number of enterprises in Paris dropped from 76,000 in 1872 to 60,000 in 1896, while in the suburbs their number grew from 11,000 to 13,000. In the heart of Paris, many workers were still employed in traditional industries such as textiles (18,000 workers), garment production (45,000 workers), and in the new industries which required highly skilled workers, such as mechanical and electrical engineering, and automobile manufacturing.[26]

Cars, airplanes and movies

Three major new French industries were born in and around Paris at almost the same time, taking advantage of the abundance of skilled engineers and technicians, and money from Paris banks. They produced the first French automobiles, aircraft, and motion pictures. In 1898, Louis Renault and his brother Marcel built their first automobile, and founded a new company to produce them. They established their first factory at Boulogne-Billancourt, just outside the city, and made the first French truck in 1906 In 1908, they built 3,595 cars, making them the largest car manufacturer in France. They received an important contract to make taxicabs for the largest Paris taxi company. When the first World War began in 1914, the Renault taxis of Paris were mobilized to carry French soldiers to the front at the First Battle of the Marne.

The French aviation pioneer Louis Blériot also established a company, Blériot Aéronautique, on boulevard Victor-Hugo in Neuilly, where he manufactured the first French airplanes. On 25 July 1909, he became the first man to fly across the English Channel. Blériot moved his company to Buc, near Versailles, where he established a private airport and a flying school. In 1910, he built the Aérobus, one of the first passenger aircraft, which could carry seven persons, the most of any aircraft of the time.

The Lumière Brothers had given the first projected showing of a motion picture La Sortie de l'usine Lumière, at the Salon Indien du Grand Café of the Hôtel Scribe, boulevard des Capucines, on December 28, 1895. A young French entrepreneur, Georges Méliés, attended the first showing, and asked the Lumière brothers for a iicense to make films. The Lumière Brothers politely declined, telling him that the cinema was for scientific purposes, and had no commercial value. Méliés persisted, and established his own small studio in 1897 in Montreuil, just east of Paris. He became a producer, director, scenarist, set designer and actor, and made hundreds of short films, including the first science-fiction film, A Trip to the Moon (Le Voyage dans la Lune), in 1902. Another French cinema pioneer and producer Charles Pathé, also built a studio in Montreuil, then moved to rue des Vignerons in Vincennes, east of Paris. His chief rival in the early French film industry, Léon Gaumont, opened his first studio at about the same time at rue des Alouettes in the 19th arrondissement, near the Buttes-Chaumont.[27]

Commerce and the department stores

.jpg)

The Belle Époque in Paris was the golden age of the Grand magasin, or department store. The first modern department store in the city, Le Bon Marché, was originally a small variety store with a staff of twelve when it was taken over by Aristide Boucicaut in 1852. Boucicaut expanded it, and by deft discount pricing, advertising, and innovative marketing (a mail order catalog, seasonal sales, fashion shows, gifts to customers, entertainment for children) turned it into a hugely successful enterprise, with a staff of eleven hundred employees and income which increased from 5 million francs in 1860 to 20 million in 1870, to reach 72 million at the time of his death in 1877. He built an enormous new building near the site of the original shop on the left bank, with an iron structure designed with the help of the engineering firm of Gustave Eiffel.

The success of Bon Marché inspired many competitors; the Grands Magasins du Louvre opened in 1855 with an income of 5 million francs, against 41 million by 1875, and 2400 employees in 1882. The Bazar de l'Hôtel de Ville (BHV) opened in 1857, and moved in a larger store in 1866. Printemps was founded in 1865 by a former department head of Bon Marché; La Samaritaine was opened in 1870; La Ville de Saint-Denis (the first building in France to have an elevator) in 1869; and Galeries Lafayette by Alphonse Kahn in 1895.[28]

High Fashion and luxury goods

At the beginning of the Belle Époque, the industry of haute couture (high fashion) was dominated by the House of Worth. Charles Worth had designed the clothes of the Empress Eugénie during the Second Empire, and turned high fashion into a veritable industry. His shop at at 7 rue de la Paix helped make that street the center of fashion. By 1900, there were more than twenty houses of haute couture in Paris, led by designers including the sons of Charles Worth, as well as Jeanne Paquin (1869-1936), Paul Poiret, Georges Doeuillet, Margaine-Lacroix, Redfern, Raudnitz, Rouff, Callot Sœurs, Blanche Lebouvier and others. Most of these houses had fewer than fifty employees, but the top six or seven firms each had between four hundred and nine hundred employees. They were concentrated on rue de la Paix and around Place Vendôme, with a few on the nearby Grands Boulevards. At the 1900 Exposition universelle, an entire building was devoted to fashion designers. The first fashion show with models had taken place in London in 1908; the idea was quickly copied in Paris. Jeanne Lanvin became a member of the Chambre syndicale de la haute couture (Syndicate of fashion designers) in 1909. Coco Chanel opened her first shop in Paris in 1910, but her fame as a designer came after the First World War.[29]

The growth of the department stores and tourism created a much larger market for luxury goods, such as perfumes,watches and jewelry. The perfumer François Coty (1874-1934) began making scents in 1904, and achieved his first success selling through department stores. He discovered the importance of elegant bottles in marketing perfume, and commissioned Baccarat and René Lalique to design bottles in the Art nouveau style. He also realized the desire of middle class consumers to have luxury goods, and sold a range of less-expensive perfumes. He also invented the fragrance set, a box of perfume, powder soap, cream and cosmetics with the same scent. He was so successful that in 1908 he built a new laboratory and factory, La Cité des Parfums ("The City of Perfume"), at Suresnes in the Paris suburbs. It had 9,000 employees and made one hundred thousand bottles of perfume a day.[30]:24

The watchmaker Louis-François Cartier opened a shop in Paris in 1847. In 1899, his grandchildren moved the shop to the rue de la Paix, and made the shop international, opening branches in London (1902), Moscow (1908) and New York (1909). His grandson Louis Cartier (1874-1942) designed one of the first purpose-built wristwatches for the Brazilian aviation pioneer Alberto Santos-Dumont, who made the first aircraft flight in Paris in 1906. The "Santos watch" went on sale in 1911, and was a huge success for the company.

-

Costume for roller skating at the Bal Bullier (1876)

-

Bicycling costumes (1898)

-

Designs by Paul Poiret (1908)

-

Evening theater dress by Jeanne Paquin (1914)

Tourism, hotels and railroad stations

The industry of mass tourism and large luxury hotels had arrived in Paris under Napoleon III, driven by new railroads and the huge crowds that had come for the first international expositions. The expositions and the crowds grew even larger during the Belle Époque; twenty-three million visitors came to Paris for the 1889 exposition, and the 1900 exposition welcomed forty-eight million visitors. The Grand Hôtel on the boulevard des Capucines had opened in 1862; the Grand Hôtel du Louvre, built for the 1855 universal exposition, opened in 1855. More luxury hotels appeared near the train stations and in the city center during the Belle Époque; the Hôtel Continental opened in 1878 on the rue de Rivoli on the site of the old Ministry of Finance, which had been burned by the Paris Commune. The Hôtel Ritz on Place Vendôme opened in 1898, and the Hôtel de Crillon on the Place de la Concorde opened in 1909.[31]

The growing number of visitors also required the enlargement of the main train stations to handle all the passengers. Gare Saint-Lazare had been covered with a forty-meter high shed between 1851 and 1853; it was further enlarged for the 1889 exposition, and a new hotel, the Terminus, built next to it. The station and its huge shed became a popular subject for painters, among them Claude Monet, during the period. A brand-new station, the Gare d'Orsay, designed by Victor Laloux, for the Compagnie d'Orléans opened on 4 July 1900; it was the first station designed for electrified trains. The line was not profitable, and the station was almost demolished in 1971, but between 1980 and 1986 it was turned into the Musée d'Orsay. Gare Montparnasse, serving western France, had been built between 1848-52. It was also enlarged between 1898 and 1900 to serve the growing number of passengers. Gare de l'Est and Gare du Nord were both expanded, and Gare de Lyon was completely rebuilt between 1895 and 1902, and given a new restaurant in the ornate style of the period, Le buffet de la Gare de Lyon, renamed the Train Bleu in 1963. [32]

From the fiacre to the taxicab

In the first part of the Belle Époque, the fiacre was the most common form of public transport for individuals; it was a box-line small horse-drawn coach with driver carrying two passengers which could be hired by the hour or by the distance of the trip. In 1900, there were about ten thousand fiacres in service in Paris; half belonged to a single company, the Compagnie générale des voitures de Paris; the other five thousand belonged to about five hundred small companies. The first two automobile taxis entered service in 1898, at a time when there were just 1,309 automobiles in Paris. The number remained very small at first; there were just eighteen in service during the 1900 Exposition, only eight in 1904, and 39 in 1905. However, by the end of 1905, the automobile taxi began to take off; there were 417 on the streets of Paris in 1906, and 1,465 at the end of 1907. Most were made by the Renault company, in their factory on the Île Seguin, an island on the Seine between Boulogne-Billancourt and Sèvres. There were four large taxi companies; the largest, the Compagnie française des automobiles de place owned more than a thousand taxis. Beginning 1898, the automobile taxis were equipped with a meter to measure the distance and calculate the fare. First called a taxamètre, it was renamed taximètre on 17 October 1904, which gave birth to the name "taxi". In 1907, Renault began building three thousand specially-built taxis; some were exported to London, and others to New York. Those which went into service in New York were named "taxi cabriolets", which was shortened in America to "taxicab". By 1913, there were seven thousand taxis on the streets of Paris.[33]

The omnibus, the tramway and the metro

At the beginning of the Belle Époque, the horse-drawn omnibus was the primary means of public transport. In 1855, Haussmann had consolidated ten private omnibus companies into a single company, the C.G.O. (Compagnie générale des Omnibus) and gave it the monopoly on public transport. The coaches of the CGO carried twenty-four to twenty-six passengers and ran on thirty-one different lines. The omnibus system was overwhelmed by the number of visitors at the 1867 Exposition, so in 1873 the city began to develop a new system of tramways. The omnibus continued to run, with larger cars that could carry forty passengers in 1880, and then, in 1888-89, a lighter vehicle which could carry thirty passengers, called an omnibus à impériale. The horse-drawn tramway gradually replaced the horse-drawn omnibus. In 1906, the first motorized omnibuses began to run on Paris streets. The last horse-drawn omnibus run took place on January 11, 1913 between Saint-Sulpice and La Villette.[34]

The horse-drawn tramway, running on a track flush with the street, had been introduced in New York in 1832. A French engineer living in New York, Loubat, brought the idea to Paris and opened the first tramway line in Paris, between place de la Concorde and the barrière de Passy in November 1853. He extended the line, known as the Chemin de fer américain, all the way across Paris from Boulogne to Vincennes in 1856. But then it was purchased by the CGO, the main omnibus line, and remained simply a curiosity. Only in 1873 did the tramway begin to gain importance, when the CGO lost its monopoly on city transport and two new companies, Tramways Nord and Tramways Sud, one financed by Belgian banks and the other by British banks, began operating from the center of Paris to the suburbs. The CGO responded by opening two new lines, one from the Louvre to Vincennes, the other following the line of fortifications around the city. By 1878, forty different lines were operating, half by the CGO. The companies tried a brief experiment with steam-powered tramways in 1876, but abandoned them in 1878. The electric-powered tramway, in service in Berlin since 1881, did not arrive in Paris until 1898, with a line from Saint-Denis to the Madeleine.[35]

When the 1900 Universal Exposition was announced in 1898, with the anticipation of millions of visitors coming to Paris, most of the public transport in Paris was still horse-drawn; forty-eight lines of omnibuses and thirty-four tramway lines still used horses, while there were just thirty-six lines of electric tramways. The last horse-drawn tramways were replaced with electric trams in 1914.

Other cities were also well ahead of Paris in introducing underground or elevated metropolitan railways: London (1863), New York (1868), Berlin (1878), Chicago (1892), Budapest (1896) and Vienna (1898) all had them before Paris. The reason for the delay was a fierce battle between the French railway companies and national government, which wanted a metropolitan system based on the existing railroad stations, that would bring passengers in from the suburbs (like the modern RER); and the Municipal Council of Paris, which wanted an independent underground metro, only in the twenty arrondissements, which would support the tramways and omnibuses on the streets. The plan of the municipality won and was approved on 30 March 1898; it called for six lines totaling sixty-five kilometers of track. They chose the Belgian method of construction, with the lines just under the surface of the street, rather than the deep tunnels of the London system.

The first line, which connected Porte de Vincennes with the Grand Palais and the other exposition sites, was built the most rapidly in just twenty months, opening on July 19, 1900, just three months after the opening the exposition. It carried more than sixteen million passengers between July and December. Line 2, between Porte Dauphine and Nation, opened in April 1903, and the modern line six was finished at the end of 1905. The earliest lines used viaducts to cross over the Seine, at Bercy, Passy and Austerlitz. The first line under the Seine, line four between Châtelet and the left bank, was built between 1905 and 1909. By 1914, the metro was carrying five hundred million passengers a year.[36]

Constructing Paris

Monuments

Most of the monuments of the period belonged to the Universal Expositions; the Eiffel Tower, Grand Palais, Petit Palais, and the Pont Alexandre III. The chief architectural legacy of the Third Republic was a large number of new schools and local city halls, all inscribed with the slogans of the Republic, and statues of allegorical symbols of the Republic, scientists, writers and political figures placed in parks and squares. The largest monument was an allegorical statue of the Republic, placed in the center of the Place du Château-d'Eau, renamed in 1879 Place de la République. It was an enormous bronze figure 9.5 meters high of the Republic holding an olive branch and standing on a pedestal 15 meters high. Allegorical statues of Liberty, Equality and Fraternity. A plaster version was placed on the pedestal on July 14, 1880, and the final bronze version was dedicated on July 14, 1883. On July 14, 1880, Place du Trône was renamed Place de la Nation, and a group of statues by Dalou, called Triumph of the Republic, was placed in the center; in the middle was Marianne, in a chariot drawn by two lions, surrounded by allegorical figures of Liberty, Work, Justice and Abundance. A plaster version was put in place in 1889, and the bronze version in 1899. A 29-meter tall monument with a statue of another republican hero, Leon Gambetta, surmounted by a pylon crowned by an eagle, was placed in the cour Napoléon of the Louvre in 1888. It was taken down in 1954 to clear the view of the Louvre; then, in 1982 it was put back up, without the pylon and eagle, on Square Édouard-Vaillant (20th arrondissement) by the socialist president François Mitterrand.[37]

Streets and boulevards

The construction of the new boulevards and streets begun by Napoleon III and Haussmann had been much criticized by Napoleon's opponents near the end of the Second Empire, but the government of the Third Republic continued his projects. The avenue de l'Opéra, boulevard Saint-Germain, avenue de la République, boulevard Henry-IV and avenue Ledru-Rollin were all completed essentially as Haussmann had planned them by 1889. After 1889, the pace of construction slowed down; boulevard Raspail was finished, rue Réaumur was extended, and several new streets were created on the left bank; rue de la Convention, rue de Vouillé, rue d'Alésia, and rue de Tolbiac. On the right bank, rue Étienne-Marcel was the last of the Haussmann projects to be completed before the First World War.[36]

While the streets planned by Haussmann were completed, the strict uniformity of façades and building heights imposed by Haussmann was gradually modified. Buildings became much larger and deeper, with two apartments on each floor facing the street and others facing only onto the courtyard. The new buildings often had ornamental rotundas or pavilions on the corners, and highly ornamental roof designs and gables. In 1902, maximum building heights were increased to 52 meters. With the advent of elevators, the most desirable apartments were no longer on the lowest floors, but on the highest floors, where there was more light, nicer view and less noise. With the arrival of automobiles and the beginning of traffic noise on the streets, the bedrooms moved to the back of the apartment, onto the courtyard. .[38]

The façades also changed from the strict symmetry of Haussmann: bay and bow windows appeared, and undulating façades. Eclectic façades became popular, mixing Louis XIV, Lous XV and Louis XVI styles, and then, with the Art nouveau, floral patterns. The most striking examples of the new architecture were the Castel Béranger on rue La Fontaine and the Hôtel Lutetia. Between 1898 and 1905, the city organized eight competitions for the most imaginative building façades; variety was given precedence over uniformity. .[38]

Architecture

.jpg)

The architectural style of theBelle Époque was eclectic, and sometimes combined elements of several different styles. While the structures of the new buildings were resolutely modern, using iron frames and reinforced concrete, the façades ranged from the Romano-Byzantine style of the Basilica of Sacré-Cœur on Montmartre, to the strange neo-Moorish Palais du Trocadéro, to the nouveau Renaissance style of the new Hôtel de Ville, to the exuberant reinvention of French of the 17th and 18th centuries classicism in the Grand Palais and Petit Palais and the Gare d'Orsay, decorated with domes, colonnades, mosaics and statuary. The most innovative buildings of the period were the Gallery of Machines at the 1889 exposition, and the new railroad stations and department stores: their classical exteriors concealed very modern interiors, with large open spaces and large glass skylights made possible by the new engineering techniques of the period. The Eiffel Tower shocked many traditional Parisians, both because of its appearance and because it was the first building in Paris taller than the cathedral of Notre-Dame.

The Art nouveau became the outstanding style of the period, particularly associated with the metro station entrances designed by Hector Guimard, and with a handful of buildings, including Guimard's Castel Béranger (1889) at 14 rue La Fontaine and the Hôtel Mezzara (1910) in the 16th arrondissement.[39] The enthusiasm for Art nouveau metro station entrances did not last long; in 1904 it was replaced at the Opera metro by a less exuberant "modern" style. Beginning in 1912, all the Guimard metro entrances were replaced with functional entrances without decoration.[40]

A revolutionary new building material, reinforced concrete, appeared at the beginning of the 20th century and quietly began to change the face of Paris. The first church built in the new material was Saint-Jean-de-Montmartre, at 19 rue des Abbesses at the foot of Montmartre. The architect was Anatole de Baudot, a student of Viollet-le-Duc. The nature of the revolution was not evident, because Baudot faced the concrete with brick and ceramic tiles in a colorful Art nouveau style, with stained glass windows in the same style.

The Théâtre des Champs-Élysées (1913) is another architectural landmark of the period, one of the few Paris buildings in the Art deco style. Designed by Auguste Perret, it was also built of reinforced concrete, and decorated by some of the leading artists of the era; bas-reliefs on the façade by Antoine Bourdelle, a dome by Maurice Denis, and paintings in the interior by Édouard Vuillard. It was the setting in 1913 for one of the major musical events of the Belle Époque, the first season of the Ballets Russes and the premiere of Igor Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring.

-

.jpg)

The Romano-Byzantine style Basilica of Sacré-Cœur (1873-1919)

-

The Gallery of Machines from the 1889 Universal Exposition

-

The Castel Béranger by Hector Guimard (1899)

-

The Grand Palais (1900)

-

The Church of Saint-Jean-de-Montmartre (1894-1904), the first church built of reinforced concrete

-

The Théâtre des Champs-Élysées (1913), in the Art deco style

Bridges

Eight new bridges were put across the Seine during the Belle Époque. The pont Sully, built in 1876, replaced two foot bridges which had connected the Île Saint-Louis to the right and left bank. The pont de Tolbiac was built in 1882], connecting the left bank with Bercy. The Pont Mirabeau, made famous in a poem by Apollinaire, was dedicated in 1895. Three bridges were built for the 1900 Exposition: the pont Alexandre-III, dedicated by the Czar Nicholas II of Russia in 1896, which connected the left bank with the grand exposition halls of the Grand Palaisand Petit Palais; the passerelle Debilly, a foot bridge which linked two sections of the Exposition; and a railroad bridge between Grenelle and Passy. Two more bridges were dedicated in 1905; the pont de Passy (now the pont de Bir-Hakeim), and the viaduc d'Austerlitz, crossed by the metro.[41]

Parks, gardens and squares

The work of creating parks, squares and promenades continued in the Second Empire style, managed by Jean-Charles Alphand, who had been the head of department of parks and promenades under Haussmann, and was elevated to the post of Director of Public Works of Paris, a position he held until his death in 1891. He was also the director of works of the 1889 universal exposition, responsible for building the Exposition's gardens and pavilions.[42] At the beginning of the Belle-Époque, Alphand finished several of the projects begun under Haussmann: Parc Montsouris, Square Boucicaut (1873), and square Popincourt (later renamed Parmentier, and still later Maurice-Gardette), which replaced a demolished slaughterhouse, and opened in 1872. His first major project of the Belle Époque was the Jardins du Trocadéro, the site of the 1878 Paris International Exposition, surrounding the enormous palais de Trocadéro, the main building of the Exposition. He filled the park with fountains, gardens and statues (the statues can now be seen on the parvis of the Musée d'Orsay), and a grotto. the park also displayed the full-sized head of the Statue of Liberty, before the statue was completed and shipped to New York. The grotto and much of the park are still as they were. The park was used again in the 1889 Exposition and, once again, with new fountains and a new palace, in the 1937 Paris Exposition.[42]

During the 1878 Exposition, Alphand had used the Champ de Mars as the site of a huge iron-framed exhibit hall, 725 meters long, surrounded by gardens. For the 1889 exposition, the same site was occupied by the Eiffel Tower and the huge Gallery of Machines, plus two large exhibit halls, the Palace of Liberal Arts and the Palace of Fine Arts. The two palaces were designed by Jean-Camille Formigé, the chief architect of Paris. The two palaces and the Gallery of Machines were demolished after the Exposition, but in 1909 Formigé was given the task of transforming the Exposition site around the Eiffel Tower into a park, with broad lawns, promenades and groves of trees, in the form it is today.[42]

Between 1895 and 1898, Formigé created another Belle Époque landmark, the Serres d'Auteuil, a complex of large greenhouses designed to grow trees and plants for all the gardens and parks of Paris. The largest structure, one hundred meters long, was designed to grow tropical plants. The greenhouses still exist today and are open to the public.

Other than the parks of the Expositions, no other large Paris parks were created in the Belle Époque, but several squares of about one hectare each were created. They all had the same basic design; with a bandstand in the center, a fence, groves of trees and flower beds, and often also had statues. These included Square Édouard-Vaillant in the 20th arrondissement (1879), Square Samuel-de-Champlain in the 20th arrondissement (1889), Square des Épinettes in the 17th arrondissement (1893), Square Scipion in the 5th arrondissement (1899), Square Paul-Painlevé in the 5th arrondissement (1899) and Square Carpeaux in the 18th arrondissement (1907).[42]

The best-known and most picturesque park of the period is that composed of Squares Willette and Nadar, on the slope directly below the Basilica of Sacré-Cœur on Montmartre. It was begun by Formigé in 1880, but not completed until 1927 by another architect, Léopold Béviére, after the death of Formigé in 1926. The park features terraces and slopes dropping eighty meters from the Basilica to the street below, and has one of the best-known views in Paris.

Street lighting

At the beginning of the Belle Époque Paris was lit by a constellation of thousands of gaslights, which were often admired by foreign visitors, and helped give the city its nickname Ville-Lumiére, the "City of Light". In 1870, there were 56,573 used exclusively to light the city streets.[43] The gas was produced by ten enormous factories around the edge of the city, located near the circle of fortifications, and was distributed in pipes installed under the new boulevards and streets. The street lights ere placed every twenty meters on the Grands Boulevards. At a predetermined minute after nightfall, a small army of 750 allumeurs in uniform, carrying long poles with small lamps at the end, went out into the streets, turned on a pipe of gas inside each lamppost, and lit the lamp. The entire city was illuminated within forty minutes. The Arc de Triomphe was crowned with a ring of gaslights, and the Champs-Élysées was lined with ribbons of white light.[43]

One of the major urban innovations in Paris was the introduction of electric street lights, to coincide with the Universal Exposition of 1878. The first streets lit were the Avenue de l'Opéra and the Place de l'Étoile, around the Arc de Triomphe. In 1881, electric street lights were added along the Grands Boulevards. Electric lighting came much more slowly for residences and businesses in some Paris neighborhoods. While in 1905 electric lights lined the Champs Élysées, there was no electric lines for households in the 20th arrondissement.[44]

The Paris Universal Expositions

The three universal expositions that took place in Paris during the Belle Époque attracted millions of visitors from around the world, and displayed the newest innovations in science and technology, from the telephone and phonograph to electric street lighting.

The 1878 Universal Exposition

The Universal Exposition of 1878, from May 1 to November 10, 1878, was designed to show the recovery of France from the 1870 Franco-German War and from the destruction of the Paris Commune. It took place on both sides of the Seine, in the Champ de Mars and heights of Trocadéro, where the first Palais de Trocadéro was built. Many of the buildings were made of new inexpensive material, called staff, composed of jute fiber, plaster of Paris, and cement. The main exposition hall was an enormous rectangular structure, the Palace of Machines, where the Eiffel Tower is located today. Inside Alexander Graham Bell displayed his new telephone, and Thomas Edison presented his phonograph. The head of the newly finished Statue of Liberty was displayed, before it was sent to New York to be attached to the body. Important congresses and conferences took place on the margins of the Exposition, including the first Congress on intellectual property, led by Victor Hugo, whose proposals led eventually to the first copyright laws, and a conference on education for the blind, which led to the adoption of the Braille system of reading for the blind. The Exposition attracted thirteen million visitors, and was a financial success.

The 1889 Universal Exposition

The Universal Exposition of 1889 took place from May 6 until October 31, 1889, and celebrated the centenary of the beginning of the French Revolution; one of the structures was a replica of the Bastille. It took place on the Champ de Mars, the hill of Chaillot, and along the Seine at the Quai d'Orsay, The most memorable feature was the Eiffel Tower, 300 meters tall when it opened (now 324 with the addition of broadcast antennas), which served as the gateway to the Exposition.[45] The Eiffel Tower remained the world's tallest structure until 1930,[46] It was not popular with everyone; its modern style was denounced in a public letter by many of France’s most prominent cultural figures, including Guy de Maupassant, Charles Gounod and Charles Garnier.[47] The largest structure was the iron-framed Gallery of Machines, at the time the largest covered interior space in the world. Other popular exhibits included the first musical fountain, lit with colored electric lights, changing in time to music. Buffalo Bill and sharpshooter Annie Oakley drew large crowds to their Wild West Show at the Exposition.[48] The Exposition welcomed 23 million visitors, [49]

The 1900 Universal Exposition

The Universal Exposition of 1900 took place from April 15 until November 12, 1900. It celebrated the turn of the century, and was by far the largest in scale of the Expositions; its sites included the Champ de Mars, Chaillot, the Grand Palais and the Petit Palais. Beside the Eiffel Tour, it featured the world’s largest ferris wheel, the Grande Roue de Paris, one hundred metres high, carrying sixteen hundred passengers in forty cars. Inside the exhibit hall, Rudolph Diesel demonstrated his new engine, and the first escalator was on display. The Exposition coincided with the 1900 Paris Olympics, the first time that the Olympic games were held outside of Greece. The Exposition popularized a new artistic style, the Art nouveau, to the world.[50] Two architectural legacies of the Exposition, the Grand Palais and Petit Palais, are still in place.[51] Though it was a great popular success, attracting an estimated forty-eight million visitors, the 1900 exposition lost money, and was the last such exposition in Paris on such a grand scale.[49]

Restaurants, cafés, and brasseries

Paris was already famous for its restaurants in the first half of the 19th century, particularly the Café Riche, the Maison dorée and the Café Anglais on the Grands Boulevards, where the wealthy personalities of Balzac's novels would dine. The Second Empire had added more luxury restaurants, particularly in the center near the new grand hotels: Durand at the Madeleine; Voisin at rue Cambon and rue Saint-Honoré; Magny on rue Mazet; and Foyot near the Luxembourg Gardens; and Maire, at the corner of the boulevards de Strasbourg and Saint-Denis, where lobster thermidor was invented. During the Belle Époque, many more prestigious restaurants could be found, particularly around the Madeleine and on the Champs-Élysées. They included Laurent, Fouquet's and the Pavillon de l'Élysée on the Champs-Élysées; the Tour d'Argent on the quai de la Tournelle; Prunier on rue Duphot; Drouant on place Gaillon; Lapérouse on the quai des Grands-Augustins; Lucas Carton at the Madeleine, and Weber on rue Royale. The most famous restaurant of the period, Maxim's, also opened its doors on the rue Royale. Two luxury restaurants were found by the lakes in the Bois de Boulogne; the Pavillon d'Armenonville and the Cascade.[52]

For those with more modest budgets, there was the Bouillon, a type of restaurant begun by a butcher named Duval in 1867, which served simple and inexpensive food, and were popular with students and visitors. One from this period, Chartier, near the Grands Boulevards, still exists.

A new type of restaurant, called a brasserie, appeared in Paris during the 1867 Universal Exposition. The name originally meant a place that brewed beer, but in 1867 it was a type of café where young women in the national costumes of different countries served different drinks of those countries, including beer, ale, chianti, and vodka. The idea was continued after the Exposition by the brasserie de l'Espérance on rue Champollion, on the left bank, and then was imitated by others. By 1890, there were forty two brasseries on the left bank, with names including the brasserie des Amours, the brasserie de la Vestale, the brasserie des Belles Marocaines, and the brasserie des Excentriques Polonais (brasserie of the eccentric Poles), and they were often used as a place to meet prostitutes.[52]

Sports

Paris played a central role in the organization of international sports, and in the professionalization of sports. The first efforts to revive the Olympic Games were led a French educator and historian, Pierre de Coubertin. The first meeting to organize the games took place at the Sorbonne in 1894, resulting in the creation of the International Olympic Committee and the holding of the first modern Olympic Games in Athens in 1896. The second games, the first Olympics held outside of Greece, were the 1900 Summer Olympics in Paris, from May 14 until October 28, 1900, organized in conjunction with the Paris Universal Exposition of 1900. There were 19 sports included in the event, and women competed in the Olympics for the first time. The swimming events took place in the Seine. Some of the sports were unusual by modern standards; they included automobile and motorcycle racing, cricket, croquet, underwater swimming, tug-of-war, and shooting live pigeons.

Cycling also became an important professional sport, with the opening in 1903 of the first cycling stadium, the Vélodrome d'hiver, on the site of the demolished Palace of Machinery from the 1900 Exposition on the Champ de Mars. The first stadium was demolished and moved in 1910 to boulevard de Grenelle. The first Tour de France, the most famous of all French cycling events, took place in 1903, with the finish line at the Parc des Princes stadium.

In September 1901, Paris hosted the first European lawn tennis championship in 1901, and on June 1, 1912, hosted the first world championship of tennis, at the stadium of the Faisanderie in the Domaine national de Saint-Cloud.

The first championship of France in football took place in 1914, with six teams competing. It was won by the team Standard Athletic Club of Paris; the team had one French player and ten British players. The first rugby match between England and France took place on March 26, 1906 at the Parc des Princes, with the victory of England.

Paris also hosted several of the world's earliest automobile races; the first, in 1894, was the Paris-Rouen race, organized by the newspaper Le Petit Journal. The first Paris-Bordeaux race took place on June 10–12, 1895, and the first race from Paris to Monte-Carlo in 1911.[53]

Science and technology

.png)

Scientists in Paris played a leading role in many of major scientific developments of the period, particularly in bacteriology and physics. Louis Pasteur (1822-1895) was a pioneer in vaccination, microbacterial fermentation and pasteurization. He developed the first vaccines against rabies (1885) and anthrax, and the process for stopping bacterial growth in milk and wine. He founded the Pasteur Institute in 1888 to carry on his work, and his tomb is located at the Institute.[54]

The physicist Henri Becquerel (1852-1908), while studying the fluorescence of uranium salts, discovered radioactivity in 1896, and in 1903 was awarded the Nobel Prize in physics for his discovery. Pierre Curie (1859-1906) and Marie Curie (1867-1934) jointly carried on Becquerel's work, discovering radium and polonium (1898). They jointly received the Nobel Prize for physics in 1903. Marie Curie became the first female professor at the University of Paris, and won the Nobel Prize for chemistry in 1911. She was the first woman to be buried in the Panthéon.[54]

The neon light was used for the first time in Paris on December 3, 1910 in the Grand Palais. The first outdoor neon advertising sign was put up on Boulevard Montmartre in 1912.[20]

The Arts

Literature

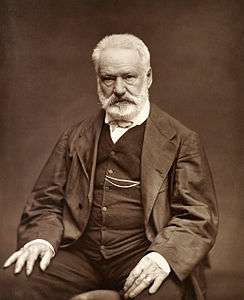

During the Belle Époque Paris was the home and inspiration for some of France's most famous writers. Victor Hugo was sixty-eight when he returned to Paris from Brussels in 1871 and took up residence on Avenue d'Eylau (now Avenue Victor Hugo) in the 16th arrondissement. He failed to be re-elected to the National Assembly, but in 1876 he was elected to the French Senate.[55] It was a difficult period for Hugo; his daughter Adèle was placed in an insane asylum, and he his longtime mistress, Juliette Drouet, died in 1883. When Hugo died May 28, 1885 at the age of eighty-three, hundreds of thousands of Parisians lined the streets to pay tribute as his coffin was taken to the Panthéon, on 1 June 1885.

Émile Zola was born in Paris in 1840, the son of an Italian engineer. He was raised by his mother in Aix-en-Provence, then returned to Paris in 1858 with his friend Paul Cézanne to attempt a literary career. He worked as a mailing clerk for the publisher Hachette, and began attracting literary attention in 1865 with his novels in the new style of naturalism. He described in intimate details the workings of Paris department stores, markets, apartment buildings and other institutions, and the lives of the Parisians. By 1877, he had become famous and wealthy from his writing. He took a central role in the Dreyfus affair, helping win justice for Alfred Dreyfus, a French artillery officer of Alsatian Jewish background, who had falsely been accused of treason.

Guy de Maupassant (1850-1893) moved to Paris in 1881 and worked as a clerk for the French Navy, then for the Ministry of Public Education, as he wrote short stories and novels at a furious pace. He became famous, but also became ill and depressed, then paranoid and suicidal, dying at the asylum of Saint-Esprit in Passy in 1893.

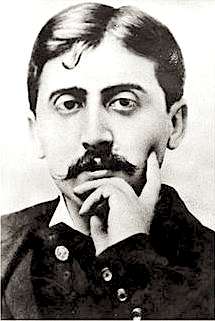

Other writers who made a mark in the Paris literary world of the Third Republic's Belle Époque included Anatole France (1844-1924); Paul Claudel (1868-1955); Alphonse Allais (1854-1905); the poet Guillaume Apollinaire (1880-1918); Maurice Barrès (1862-1923); René Bazin (1853-1932); Colette (1873-1954); the poet and novelist François Coppée (1842-1908); Alphonse Daudet (1840-1897); Alain Fournier (1886-1914), author of Le Grand Meaulnes (1913)- his only published novel-, who died on the battlefield in September 1914; André Gide (1869-1951); Pierre Louÿs (1870-1925); Maurice Maeterlinck (1862-1949), a Belgian poet and essayist; the symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé (1840-1898), who had a literary salon every Tuesday including the leading artists and writers of Paris; Octave Mirbeau (1848-1917); Anna de Noailles (1876-1933), poet and novelist; Charles Péguy (1873-1914), killed at the front on 5 September 1914; Marcel Proust (1871-1922), born in the first year of the Belle Époque, completed in 1913 the first part of In Search of Lost Time, begun in 1902; Jules Renard (1864-1910); Arthur Rimbaud (1854-1891), the young poet with whom Verlaine had a passionate but disastrous affair; Romain Rolland (1866-1944); Edmond Rostand (1868-1918), author of the world-renowned Cyrano de Bergerac; Paul Verlaine (1844-1890). Paris was also the home of one of the greatest Russian writers of the period, Ivan Turgenev.

-

Guy de Maupassant (1888)

-

Paul Verlaine (1893)

-

Stéphane Mallarmé (1896)

-

Marcel Proust (1900)

-

Emile Zola (1902)

Music

Paris composers during the period had a major impact on European music, moving it away from romanticism toward impressionism in music and modernism.

Camille Saint-Saëns (1835-1921) was born in Paris on rue du Jardinet in the 6th arrondissement, and was admitted to the Paris Conservatoire when he was thirteen. When he finished the Conservatory, he became organist at the church of Saint-Merri, and later at La Madeleine. During the Belle Époque he lived on rue Monsieur-le-Prince in the Latin Quarter. His most famous works included the Danse Macabre, the opera Samson et Dalila (1877), the Carnival of the Animals (1877), and his Symphonie No. 3 "avec orgue" in C minor, op. 78 (1886). On 25 February 1871, he co-founded with Romain Bussine the Société nationale de musique, to promote French contemporary and chamber music. His students included Maurice Ravel and Gabriel Fauré, two of the foremost French composers of before and after World War I.[56]

Georges Bizet (1838-1875), born in Paris, was admitted to the Paris Conservatoire when he was only ten years old. He finished his most famous work, Carmen, written for the Opéra-Comique, in 1874. Even before opening, Carmen was criticized as immoral, the musicians complained that it could not be played, and the singers complained that it could be not be sung. The reviews were unfavorable, and the audience cold; and when Bizet died in 1875, he considered it a failure. Nonetheless, Carmen became one of the best-known and beloved operas in the repertoire, worldwide.[57]

The most famous French composer of the late Belle Époque in Paris was Claude Debussy (1862-1918). He was born at Saint-Germain-en-Laye, near Paris, and entered the Conservatory in 1872. He became part of the Parisian literary circle of the symbolist poet Mallarmé, and an admirer of Wagner, then went on to experiment with impressionism in music, atonal music and chromaticism. His most famous works included Clair de Lune (1890), La Mer (1905) and the opera Pelléas et Mélisande (1903-1905). He lived at 23 square de l'Avenue-Foch in the 16th arrondissement from 1905 until his death in 1918.[58]

The most revolutionary composer to work in Paris was the Russian-born Igor Stravinsky. He first achieved international fame with three ballets commissioned by the impresario Sergei Diaghilev and first performed in Paris by Diaghilev's Ballets Russes: The Firebird (1910), Petrushka (1911) and The Rite of Spring (1913). The last of these transformed the way in which subsequent composers thought about rhythmic structure.

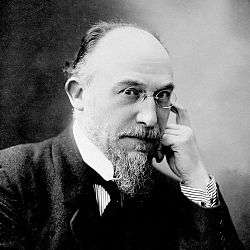

Other influential composers in Paris during the period included Jules Massenet (1842-1912), author of the operas Manon and Werther; and Eric Satie (1866-1925), who, after leaving the Conservatory, made his living as a pianist at Le Chat Noir, a cabaret on Montmartre. His most famous works were the Gymnopédies (1888).[59]

-

Georges Bizet (1875)

-

Camille Saint-Saëns (about 1880)

-

Jules Massenet (1880)

-

Igor Stravinsky, as drawn by Picasso (1920)

Painting

Paris was the home and the frequent subject of the impressionists, who tried to capture the city's light, its colors, and its motion. While they painted in many different places, they and future artists survived and flourished because of the support of Paris art dealers, such as Ambroise Vollard and Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, and wealthy patrons, including Gertrude Stein,

The first exhibit of tho impressionists took place from April 15 to May 15, 1874 in the studio of the photographer Nadar. It was open to any painter who could pay a fee of sixty francs. Claude Monet showed the painting, "Impression: Sunrise" (Impression, soleil levant), which gave the movement its name. Other artists who took part included Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Berthe Morisot, Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro, and Paul Cezanne.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901) spent much of his short life in Montmartre, painting and drawing the dancers in cabarets. He produced 737 canvases in his lifetime, thousands of drawings and a series of posters made for the cabaret Moulin Rouge. Many other artists lived and worked in Montmartre where rent was low and the atmosphere congenial. In 1876, Auguste Renoir rented space at 12 rue Cartot to paint Bal du moulin de la Galette, showing a popular ball at Montmartre on a Sunday afternoon. Maurice Utrillo lived at the same address from 1906 to 1914, and Raoul Dufy shared an atelier there from 1901 to 1911. The building is now the Musée de Montmartre.[60]

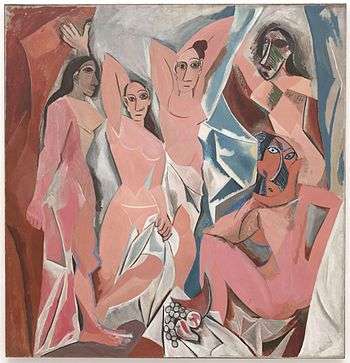

A new generation of artists arrived in Montmartre at the turn of the century. Drawn by the reputation of Paris as the world capital of art. Pablo Picasso came from Barcelona in 1900, sharing an apartment with the poet Max Ernst, and began by painting the cabarets and prostitutes of the neighborhood. Amedeo Modigliani and other artists lived and worked in a building called Le Bateau-Lavoir during the years 1904–1909: where in 1909 Picasso painted one of his most important masterpieces, Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. Led by Picasso and Georges Braque, the artistic movement cubism was born in Paris.[61]

Henri Matisse came to Paris in 1891 to study at the Académie Julien in the class of painter Gustave Moreau, who advised him to copy paintings in the Louvre and to study Islamic Art, which Matisse did. He also made the acquaintance of Raoul Dufy, Cézanne, Georges Rouault and Paul Gaugin, and began to paint in the style of Cézanne. Matisse visited Saint-Tropez in 1905, and when he returned to Paris, he painted a revolutionary work, Luxe, Calme et Volupté, using bright colors and bold dabs of paint.[61] Matisse and artists such as André Derain, Raoul Dufy, Jean Metzinger, Maurice de Vlaminck and Charles Camoin revolutionized the Paris art world with "wild", multi-colored, expressive landscapes and figure paintings that the critics called Fauvism. Henri Matisse's two versions of The Dance (1909) signified a key point in the development of modern painting.[62]

The Paris Salon, which had established the reputations and measured the success of painters throughout the Second Empire, continued to take place under the Third Republic until 1881, when a more radical French government denied it official sponsorship. It was replaced by a new Salon sponsored by the Société des Artistes Français, In December 1890, the leader of the society, William-Adolphe Bouguereau, propagated the idea that the new Salon should be an exhibition of young, yet not awarded, artists. Ernest Meissonier, Puvis de Chavannes, Auguste Rodin and others rejected this proposal and made a secession. They created the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts and its own exhibition, immediately referred to in the press as the Salon du Champ de Mars [63] or the Salon de la Société Nationale des Beaux–Arts;[64] it was soon also widely known as the Nationale. In 1903, in response to what many artists at the time felt was a bureaucratic and conservative organization, a group of painters and sculptors led by Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Auguste Rodin organized the Salon d'automne.

-

Claude Monet by Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1875)

-

.jpg)

Self-portrait of Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1876)

-

Henri Matisse (1913)

Sculpture

The Belle Époque was a golden age for sculptors; the government of the Third Republic commissioned very few monumental buildings, but did commission a large number of statues to French writers, scientists, artists and political figures, which soon filled the city's parks and squares. The most prominent sculptor of the period was Auguste Rodin (1840-1917). Born in Paris into a working-class family, he was rejected for entry into the Ecole des Beaux-Arts and rejected by the Paris Salon. He had to struggle for many years to win recognition, supporting himself as a decorator and later as a designer for the Sèvres porcelain factory. He gradually won attention for his design for the Gates of Hell, for a museum of decorative art which was never built; its plan included what became his most famous work, The Thinker. He was commissioned by the city of Calais to make a monument, The Burghers of Calais (1884), commemorating a marking event that took place in that city in 1347, during the Hundred Years' War. He was also commissioned to make a monument to Balzac (now on boulevard Raspail), which caused a scandal and made him a celebrity. Rodin's work was exhibited near the 1900 Exposition, which won him many foreign clients. In 1908, he moved from Meudon to Paris, renting the ground floor of a private mansion in the 7th arrondissement, the Hôtel Biron, now Musée Rodin. By the time of his death, he was the most famous sculptor in France, perhaps in the world.[65]

Other more traditional sculptors whose work won acclaim in Paris during the Belle Époque included Jules Dalou, Antoine Bourdelle (also a former assistant of Rodin), and Aristide Maillol. Their works decorated theaters, parks, and were featured at the International Expositions. The more avant-garde artists organized themselves into the Société des Artistes indépendants, holding annual Salons, which helped set the course of modern art. At the turn of the century, Paris attracted sculptors from around the world. Constantin Brancusi (1876-1957) moved from Bucharest to Munich to Paris, where he was admitted, in 1905, to the École des beaux-arts. He worked for two months in the workshop of Rodin, but left, declaring that "Nothing grows under big trees", and went in his own direction into modernism. Brancusi won fame at the 1913 Salon des indépendants and became one of the pioneers of modern sculpture.[66]

The flood of 1910

.jpg)

The Paris flood of 1910 reached the height of 8.5 meters on the scale measuring the river's level on the pont de la Tournelle. The Seine rose above its banks and flooded along the course it had followed in prehistoric times; the water reached as far as the gare Saint-Lazare and the place du Havre. It was the second-highest flood recorded in the history of Paris (the highest was 8.1 meters in 1658), and was the third major flood of the Belle Époque (the others were in 1872 and 1876), but it received much more attention than earlier floods, largely because of the advent of photography and the international press. Postcards and other images of the flood spread around the world. The municipal authorities made a special survey of the city to measure exactly its extent. It also demonstrated the vulnerability of the city's new infrastructure: the flood stopped the Paris Metro, and shut down the city's electricity and telephone system. Afterwards, new dams were constructed along the Seine and its major tributaries. No comparable floods have taken place since. [67]

The end of the Belle Époque

On June 28, 1914 the news reached Paris of the assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria by Serbian nationalists in Sarajevo. Austria declared war on Serbia on 28 July, and following the terms of their alliances, Germany joined Austria, while Russia, Britain and France declared against Austria and Germany on August 1. 1914. On the day before the declaration of war, the leader of the French socialists, Jean Jaurès, was assassinated by a mentally-disturbed man in the café du Croissant near the headquarters of the socialist newspaper L'Humanité, in Montmartre. The new war was supported by both French nationalists, who saw an opportunity to gain back Alsace and Lorraine from Germany; and by most on the left, which saw an opportunity to overthrow the regimes in Germany and Austria. Parisian men of military age were ordered to report to mobilization points in the city; only one percent did not appear.[68]

The German army rapidly approached Paris. On August 30, a German plane dropped three bombs on the rue des Récollets, the quai de Valmy and the rue des Vinaigriers, killing one woman. Planes dropped bombs on August 31 and September 1. On September 2, a bulletin of the military governor of Paris announced that the French government had left the city "in order to give a new impulsion to the defense of the nation." On September 6, six hundred Parisian taxis were called upon to carry soldiers to the front lines of the First Battle of the Marne. The offensive of the Germans was stopped and their army pulled back. Parisians were urged to leave the city; by September 8, the population of the city had fallen to 1,800,000, or 63 percent of the population in 1911. For the Parisians, four more years of war and hardship lay ahead. The Belle Époque had become just a memory.[68]

Chronology

1871-1899

- 1872

- Population: 1,850,000 [69]

- 13 January – opening of the École libre des sciences politiques, or Sciences-Po.

- 1873

- 24 July – Law passed supporting the construction of the Basilica of Sacré-Cœur on Montmartre, financed by private contributions.

- 1874

- French government returns to Paris. MacMahon, first president of the French Third Republic moves into the Élysée Palace.

- 7 May – Société de l'histoire de Paris et de l'Île-de-France founded at the École nationale des chartes.[70]

- 15 April – First Paris exhibit by Impressionist painters in the studio of the photographer Nadar. [71]

- 12 August – Opening of canal bringing the water of the Vannes river to Paris.

- 1875

The Grand stairway of the Paris Opera (1875)

The Grand stairway of the Paris Opera (1875)- 5 January – Opening of the Palais Garnier opera house.

- 3 March: Premiere of Bizet's opera Carmen.

- 15 June – first stone placed of the Basilica of Sacré-Cœur.

- 1877

- Population: 1,985,000 [69]

- 1878

- 1 May – Opening of the Exposition Universelle (1878) held at the Trocadero Palace and on the Champ de Mars.

- 30 May – The first test of electric lighting on the avenue de l'Opéra and the Place de l'Etoile. [72]

- 1879

- July – Installation of first telephone system in Paris.

- 1880