Paulins Kill

| Paulinskill | |

| Country | United States |

|---|---|

| State | New Jersey |

| Counties | Sussex, Warren |

| Source | |

| - location | Fredon Township, Sussex County |

| - elevation | 750 ft (229 m) |

| - coordinates | 41°04′01″N 74°46′23″W / 41.06694°N 74.77306°W [1] |

| Mouth | Delaware River |

| - location | Knowlton Township, Warren County |

| - elevation | 262 ft (80 m) [1] |

| - coordinates | 40°55′10″N 75°05′16″W / 40.91944°N 75.08778°WCoordinates: 40°55′10″N 75°05′16″W / 40.91944°N 75.08778°W [1] |

| Length | 41.6 mi (66.9 km) [1] |

| Basin | 177 sq mi (458 km2) [2] |

| Discharge | for Blairstown, New Jersey |

| - average | 76 cu ft/s (2.15 m3/s) [3] |

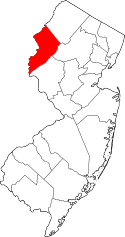

The Paulins Kill drains an area of 177 square miles (460 km2) in northwestern New Jersey and is part of the Delaware River watershed | |

The Paulinskill (also known as Lake Paulinskill or Paulinskill River) is a 41.6-mile (66.9 km)[1] tributary of the Delaware River in northwestern New Jersey in the United States. With a long-term median flow rate of 76 cubic feet of water per second (2.15 m³/s), it is New Jersey's third-largest contributor to the Delaware River, behind the Musconetcong River and Maurice River.[4] The Paulinskill drains an area of 176.85 square miles (458.0 km2) across portions of Sussex and Warren counties and 11 municipalities. The Paulinskill flows north from its source near Newton, and then turns southwest. The river sits in the Ridge and Valley geophysical province.

The Paulinskill was a conduit for the emigration of Palatine Germans who settled in northwestern New Jersey and northeastern Pennsylvania during the colonial period and the American Revolution. Remnants of their chiefly agricultural settlements are still found in local architecture, cemeteries, farms and mills, and the area remains largely rural.

Flowing through rural sections of Sussex and Warren counties, the Paulinskill is regarded as an excellent place for fly fishing. The surrounding area is used for hiking and other forms of recreation such as observing birds and other wildlife.

Course

The main branch of the Paulinskill begins to form immediately north of Newton, in the marshes that straddle the town. The headwaters start near Route 622 in Fredon Township.[1] The Paulinskill flows southwest for the rest of its journey, through Hampton and Stillwater townships in Sussex County. Trout Brook, which rises on Kittatinny Mountain, flows into the Paulinskill near Middleville in Stillwater Township. Swartswood Lake feeds Trout Brook through Keen's Mill Brook. The Paulinskill continues its course southwest, entering Warren County, where it initially forms the border between Frelinghuysen and Hardwick townships. It enters Blairstown immediately after, where it is joined by Blair Creek, named (as is the town) for John Insley Blair (1802–1899), as well as Jacksonburg Creek, Susquehanna Creek, Dilts Creek and Walnut Creek. Yards Creek, which rises at the Yards Creek reservoir in Blairstown, enters the Paulins Kill near the hamlet of Hainesburg in Knowlton Township. Finally, in Warren County its waters enter the Delaware River just south of the Delaware Water Gap at the hamlet of Columbia in Knowlton Township.[1]

After the establishment of Swartswood State Park in 1914, a dam was built in the 1920s across the Paulinskill in Stillwater Township to create Paulinskill Lake. Summer cottages were built to attract vacationers from nearby New York City. Today, Paulinskill Lake is a private, year-round residential community with over 500 homes.[5][6]

Watershed

The Paulinskill drains a portion of the Kittatinny Valley watershed. Kittatinny Valley is bordered to the northwest by the Kittatinny Ridge segment of the Ridge and Valley Appalachian Mountains, and to the southeast by the New Jersey Highlands.[7] High Point, near the northeastern end of the ridge, is the highest peak in New Jersey, reaching an elevation of 1,800 feet (550 m).[8]

The lower southern and eastern portions of the valley are drained by the Paulinskill and the Pequest River, which flow generally south to the Delaware River watershed.[9] The upper northwestern area is drained by the Big Flatbrook River to the Delaware River watershed in the south.[10] The Wallkill River drains the northeastern portion of the valley, flowing north to the Hudson River watershed.[11]

History

Origins of the name

The U.S. Geological Survey Board of Geographic Names decided that the official spelling of the name would be Paulins Kill in 1898.[1] Other spellings (Pawlins Kill or Paulinskill) have remained in common use. Kill is a Dutch word for "stream".[12]

Local tradition says that the Paulins Kill was named for a girl named Pauline, the daughter of a Hessian soldier. During the American Revolution, Hessian soldiers captured at the Battle of Trenton and other skirmishes within New Jersey were held as prisoners of war in the Stillwater area. Several of these Hessians are alleged to have deserted the British and taken up residence in Stillwater because of the village's predominantly German emigrant population. The assumption is that the name Paulins Kill was derived from "Pauline's Kill".[13][14] However, the fact that the name Paulins Kill is present on maps and surveys dating from the 1740s and 1750s—two and three decades before the Revolution—negates the veracity of this tradition.[15]

Two other possibilities for the naming of the Paulins Kill are more likely. First, that the wife of one of the area's first settlers, Johan Peter Bernhardt (died 1748), was named Maria Paulina and that she had died prior to the first settlement at Stillwater in 1742. However, very few records are extant detailing Bernhardt's family. The second and most likely etymological origin is that the Native American name given to the mountain on the valley's western flank, Pahaqualong (also spelled Pahaqualin, Pohoqualin and Pahaquarra) may have been corrupted and anglicized to a spelling such as "Paulins" by early white settlers or surveyors. Pahaqualong is roughly translated as "end of two mountains with stream between", from a combination of the words pe’uck meaning "water hole," qua meaning "boundary," and the suffix -onk meaning "place."[16][17] This translation is thought to refer either to the valley of the Paulins Kill itself, or to the Delaware Water Gap. Local tradition does place an Indian village named Pahaquarra near the mouth of the Paulinskill which is immediately south of the Delaware Water Gap. Likewise, the former Pahaquarry Township in Warren County derived its name from this origin.[18]

A village named Paulina located a short distance east of Blairstown on Route 94, is said to have been named "from the stream upon which it is located." William Armstrong, a local settler, built the first grist mill there along the river in 1768, and the village took root.[19]

The Paulins Kill was originally known as the Tockhockonetcong by the local Native Americans, who were likely Munsee, a tribe or phratry of the Lenni Lenape. The name Tockhockonetcong (or Tockhockonetcunk) roughly translates to "stream that comes from Tok-Hok-Nok"—Tok-hok-nok being an Indian village believed to have been within the boundaries of present-day Newton, New Jersey,[18] near which the eastern (main) branch of the Paulins Kill begins, and the Lenape roots hannek meaning "stream" and the suffix -ong denoting "place".[20]

Early settlement

The first human settlement along the Paulins Kill was by early Native Americans circa 8,000–10,000 BC at the close of the last ice age (known as the Wisconsin glaciation). At the time of the first settlement by emigrating Europeans in this region, it was populated by the Munsee tribe of the Lenni Lenape (or Delaware) Indians. Artifacts (often of stone, clay or bone) of the Native American culture are often found in nearby farm fields and at the site of their ancient villages.[21][22]

Typically, early European settlement along the Paulins Kill was by Palatine Germans who had emigrated to the New World via the port of Philadelphia from 1720 to 1800. Many had trekked north through the valley of the Delaware and settled along the Musconetcong, Pequest and Paulins Kill valleys in New Jersey and along the Lehigh River valley in Pennsylvania. Areas along the Paulins Kill generally were not settled until the 1740s and 1750s.[23] Often villages established and settled by German emigrants remained culturally German well into the Nineteenth Century, with German Lutheran and Reformed churches (often as "Union" churches) established shortly after the first settlements (as was the case in Knowlton and in Stillwater). However, by the early Nineteenth Century, many descendants of these German settlers removed to newly opened lands in the West (i.e. Ohio, the Northwest Territory, the Southern Tier of New York) and those that remained had assimilated into English-speaking culture, and the German Reformed or Lutheran Churches often became Presbyterian.[24][25] The German cultural impact of this community can still be seen in local architecture—most notably in barns and in stone houses—and in cemeteries containing intricately carved gravestones often bearing archaic German text and funerary symbols.[26] English, Scottish, and Welsh settlers located in the Paulins Kill valley throughout the latter half of the eighteenth century, often traveled north from Philadelphia, or west from Long Island, Newark, and Elizabethtown (now Elizabeth).[27][28][29][30]

The area around present-day Stillwater was first settled by the family of Casper Shafer (1712–1784), a Palatine German who had emigrated to Philadelphia a few years earlier. Shafer, with his father-in-law, Johan Peter Bernhardt (?–1748), and his brother-in-law Johann Georg Windemuth (or John George Wintermute) (1711–1782), settled at Stillwater in 1742. Both Shafer and Windemuth were married to Bernhardt's daughters.[31][32] Shafer, who operated a grist mill at Stillwater starting in 1746, transported flour, fruit, and other products by flatboat down the Paulins Kill and the Delaware River to the market in Philadelphia. Most of the New Jersey shoreline and cities such as Elizabethtown and Newark were practically unknown to the German settlers along the Paulins Kill who learned of the existence of these cities only through trade with the local Lenni Lenape.[28][33]

The first road connecting Elizabethtown, and Morristown with settlements along the Delaware River, was the Military Road built by Jonathan Hampton (1711–1777) in 1755–1756.[34] This road, which crosses the Paulins Kill at present-day Baleville, in Hampton Township, was built to supply fortifications built in the Delaware valley at this time to protect New Jersey during the French and Indian War. Very few passable, large roads were built in this section of New Jersey, then largely a sparsely populated wilderness, before the creation of turnpike companies in the early decades of the Nineteenth Century. During much of the mid-eighteenth century, trade in the northwestern reaches of New Jersey was conducted through Philadelphia by way of the Delaware River.[35]

About the year 1760, Mark Thomson (1739–1803) settled in Hardwick Township (now Frelinghuysen Township) and erected a gristmill and sawmill on the Paulins Kill. The settlement that arose was later named Marksboro in his honour. Thomson, who removed to Changewater in Hunterdon County, became an officer in the Continental Army during the American Revolution, and served two terms in the House of Representatives.[28]

Commercial and industrial impact

Chiefly a pastoral river in a largely undeveloped area of New Jersey, the Paulins Kill has remained generally unaffected by industrial pollution. Dams were erected to power various small-town gristmills, sawmills, oil expellers, and fulling mills,[28] and the electrical power plant at Branchville established in 1903. Columbia, a hamlet near the mouth of the Paulins Kill in Knowlton Township, was known for a large glass manufacturing factory. In recent decades, the dams have been breached or no longer impede the flow of the river.[36]

Still, pollution reaches the Paulins Kill from nearby residential developments and farm run-off containing agricultural pesticides and fertilizers. Several farms along the banks of the Paulins Kill produce alfalfa, wheat, corn, hay (and historically, barley, buckwheat and rye). Fruit trees in orchards produce cherries, apples, plums, peaches and pears, while native wild grape vines, and blackberry bushes are also found in the valley.[35] New Jersey's Department of Environmental Protection occasionally brings civil actions against local firms that pollute in the Paulins Kill watershed, such as a $121,500 fine for a Sussex County shopping mall sewage treatment facility which discharged pollutants into a tributary of the Paulins Kill between 1996 and 1998.[37]

The New Jersey Public Interest Research Group (NJPIRG) has ranked the Paulins Kill as the seventh in a collection of rivers and creeks in a Top 30 listing of New Jersey waterways to Save[38] The Paulins Kill is home to a wide variety of amphibians, including the spotted salamander, red-spotted newt, American toad, Fowler's toad, American bullfrog and others.[39] In 2000, a public sewer and water project in Branchville, New Jersey, was suspended out of concern for dwarf wedgemussels (Alasmidonta heterodon), an endangered species, and restarted in 2002.[40]

Near Columbia, the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad built the Paulinskill Viaduct (known also as the Hainesburg Viaduct), a bridge crossing the Paulins Kill, for the Lackawanna Cut-Off rail corridor. Begun in 1908, this bridge was deemed an engineering marvel for its use of reinforced concrete. Spanning 1,100 feet (335 m) across the Paulins Kill Valley, the Viaduct rises 115 feet (35 m) above the valley floor, and opened for rail traffic in 1911.[41][42][43] It was the largest concrete viaduct in the world until 1915, when the Lackawanna Railroad opened the Tunkhannock Viaduct in Nicholson, Pennsylvania, spanning over twice the Paulinskill Viaduct's length.[44] Currently abandoned, several plans are underway by New Jersey Transit to open the route as a passenger line to Scranton, Pennsylvania.[45] This site is commonly visited by adventure-seeking individuals.[46]

Today

The Paulins Kill continues to maintain its rural character through both local concern and government policy. It is an excellent area for birdwatching, canoeing, hiking, hunting and fishing, and is considered to be one of the best trout streams in New Jersey.[47]

Fishing

The Paulins Kill is a popular fishing destination for various species of trout, such as rainbow trout, brown trout and brook trout. Trout are stocked each year during the spring fishing season by New Jersey's Division of Fish & Wildlife. Hardly any wild trout are found. This is due to the river getting shallow in summer and warm. The river owes its fly fishing reputation largely to the prolific populations of various species of the mayfly and caddisfly.[48] Historically, the Paulins Kill was known to be populated with American shad, but with the construction of mill dams across the river in the eighteenth and nineteenth century, the shad were unable to spawn in the river.[49] Shad can still be found in the Delaware River.[50]

Protected areas

The Paulins Kill valley contains many protected areas. Swartswood State Park, established in 1914 as the first and oldest state park in New Jersey, is on 2,272 acres (919 ha) just north of Paulins Kill Lake in Sussex County.[51] Along Kittatinny Ridge in the northern part of the watershed are parts of Worthington State Forest (west), Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area (central), and Stokes State Forests (east).[52][53][54] In addition to these state forests, the Paulins Kill valley is host to a variety of common coniferous and deciduous trees, which have been harvested for lumber in the past, including: white oak and black oak, buttonwood, eastern red cedar, eastern hemlock, American chestnut, black walnut, tamarack larch, spruce, and pine. Trees that add to the beauty of the fall foliage include maple, birch, hickory, elm, and crab apple.[55]

New Jersey's Green Acres program has targeted the Paulins Kill and its surrounding valley as an excellent natural resources for open space and farmland preservation and recreational opportunities. The state, working together with agricultural development boards in Sussex and Warren Counties, and with the Ridge and Valley Conservancy, a local nonprofit land trust, share land acquisition costs to enter tracts of real estate into the program.[56] Since 1983, several farms across New Jersey have sold development rights to the county programs. Sussex County has permanently preserved 12,242 acres (4,954 ha) of woodland and farmland.[57] Likewise, Warren County has preserved 100 farm properties, comprising over 12,200 acres (4,900 ha).[58]

In addition, four Wildlife Management Areas (WMAs) are in the Paulins Kill valley area: Bear Swamp WMA, Trout Brook WMA, White Lake WMA, and Columbia Lake WMA. Together they comprise 6,564 acres (2656 ha) of protected lands, mostly acquired through "Green Acres" funds.[59] Hunting and trapping are permitted in season in many of these protected areas. Common game animals include white-tailed deer, eastern coyote, red fox, gray fox, opossum, eastern cottontail rabbit, raccoon, gray and red squirrel, beaver, muskrat, and woodchuck or groundhog. Common game birds include ring-necked pheasant, eastern wild turkey, American crow, and Canada goose.[60]

The Paulins Kill watershed is home to a variety of other animals. Other mammals include eastern chipmunk, porcupine, black bear, striped skunk, river otter, and bobcat.[61] Common northeastern American reptiles found there include snakes such as the American copperhead, eastern diamondback rattlesnake, northern water snake, common garter snake and milk snake, and turtles, including the eastern box turtle, and common snapping turtle.[62]

Hiking

The Paulinskill Valley Trail—a network of rail trails along abandoned railroad beds of the New York, Susquehanna and Western Railroad—have been transformed and maintained for hiking, horseback riding, and other recreational uses, stretches for 27 miles (43 km) from Sparta Junction in Sussex County to Columbia in Warren County, roughly following the entire length of the river. After the New York, Susquehanna and Western decommissioned the route in 1962, the right-of-way along this corridor was purchased by the City of Newark the following year. Newark hoped to use the bed for a water pipeline connecting to the proposed dam and reservoir project on the Delaware River. However, this project—controversial from the start because of environmental concerns and the federal government's abuse of eminent domain—was canceled during the 1970s. Newark sold their claim to the corridor in 1992 to the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection for $600,000, and the Paulinskill Valley Trail was created.[63] The Appalachian Trail follows the top of Kittatinny Ridge at the northern edge of the valley.[52]

Birdwatching

Birdwatchers have sighted a variety of common and endangered species of birds that inhabit New Jersey. More common species include: American robin, barn swallow, field sparrow, blue jay, black-capped chickadee, northern cardinal, red-winged blackbird and the American goldfinch. Also sighted are several species of woodpecker, including red-headed, red-bellied, and downy, and the endangered pileated woodpecker, as well as the yellow-bellied sapsucker. Often sighted are water fowl such as the mute swan, the wood duck, and the mallard, wading birds such as the killdeer, and predators such as the red-tailed hawk. More rare birds sighted in the Paulins Kill valley include: purple martin, scarlet tanager, indigo bunting, Baltimore oriole, purple finch, and a variety of owls, notably the barn, eastern screech, great horned, snowy, barred, and northern saw-whet owl.[64]

In art, literature and popular culture

- Essayist, poet and children's author Aline Murray Kilmer (1886–1941), the widow of poet Joyce Kilmer (1886–1918) lived in Stillwater, New Jersey, for the last 13 years of her life. Her 1785 house, "Whitehall," was built along the Paulins Kill by Abraham Shafer (1754–1820), son of Casper Shafer. It is thought that the setting of her children's book, A Buttonwood Summer (1929), was inspired by Stillwater and the Paulins Kill valley.[65]

- The 1980 slasher film Friday the 13th was filmed at Camp NoBeBosCo north of Blairstown, New Jersey, in Hardwick Township. The camp's Sand Pond, which stood in for the movie's "Crystal Lake," feeds the Jacksonburg Creek, a tributary of the Paulins Kill.[66]

- Artist and Queens College professor Louis Finkelstein (1923–2000) created a painting entitled Trees at Paulinskill (c.1991–97) that was among his later pastel works and critically compared to works by French artist and Post-Impressionist painter Paul Cézanne (1839–1906).[67][68]

See also

- Geography of New Jersey

- History of New Jersey

- Kittatinny Valley State Park

- List of New Jersey rivers

- New Jersey

- Paulinskill Viaduct

- Swartswood State Park

Resources

Notes and citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Geographic Names Information System, United States Geological Survey (August 2, 1979). "Geographic Names Information System Feature Detail Report: Paulins Kill". Retrieved January 2, 2015.

- ↑ Watershed Reference Map from Flood Insurance Claims in the Delaware River Basin: Comparative Analysis of Flood Insurance Claims in the Delaware River Basin, September 2004 and April 2005 Floods, no further authorship information given, accessed August 24, 2006.

- ↑ USGS National Water Information System: Web Interface - Real-Time Data for New Jersey: Streamflow no further authorship information given, accessed August 24, 2006.

- ↑ USGS National Water Information System: Web Interface - Real-Time Data for New Jersey: Streamflow no further authorship information given, accessed October 30, 2006.

- ↑ "About the PLA". Paulinskill Lake Association. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- ↑ "Business Man's Summer Retreat" (PDF). Philadelphia Magazine. June 1951. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- ↑ "Hudson–Kittatinny Valley". Landscape Classification for the Hudson Valley Section of New Jersey (PDF) (Report). New Jersey Forest Service. May 2000. p. 9. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- ↑ "Kittatinny-Shawangunk Ridge and Valley". Landscape Classification for the Hudson Valley Section of New Jersey (PDF) (Report). New Jersey Forest Service. May 2000. p. 40. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- ↑ "Lower Kittatinny Valley". Landscape Classification for the Hudson Valley Section of New Jersey (PDF) (Report). New Jersey Forest Service. May 2000. p. 28. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- ↑ "Kittatinny-Shawangunk Ridge and Valley". Landscape Classification for the Hudson Valley Section of New Jersey (PDF) (Report). New Jersey Forest Service. May 2000. p. 40. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- ↑ "Hydrology". Landscape Classification for the Hudson Valley Section of New Jersey (PDF) (Report). New Jersey Forest Service. May 2000. p. 11. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- ↑ "A fishy name will stay the same" by Mary Ann McRae (September 6, 1996), CNN.

- ↑ Northwestern New Jersey—A History of Somerset, Morris, Hunterdon, Warren, and Sussex Counties, Vol. 1. (A. Van Doren Honeyman, ed. in chief, Lewis Historical Publishing Co., New York, 1927), 499

- ↑ Snell, James P. (1881) History of Sussex and Warren Counties, New Jersey, With Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of Its Prominent Men and Pioneers. (Philadelphia: Everts & Peck, 1881), 379.

- ↑ Labelled "Tockhockonetkunk or Pawlings Kill" on an untitled map of Jonathan Hampton (1758) in the collection of the New Jersey Historical Society, Newark, New Jersey; also Documents Relating to the Colonial, Revolutionary and Post-Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey. [Title Varies]. Archives of the State of New Jersey, 1st–2nd series. 47 volumes. Newark, New Jersey, 1880–1949, passim.

- ↑ Decker, Amelia Stickney, That Ancient Trail (Trenton, New Jersey: Privately printed, 1942), 151

- ↑ Anthony and Brinton, op. cit.

- 1 2 Snell, op. cit., 23

- ↑ Snell, op. cit., 688.

- ↑ Anthony, A. S., Rev. and Brinton, Daniel G. Lenape-English Dictionary. (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: The Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1883).

- ↑ Schrabisch, Max. Indian habitations in Sussex County, New Jersey Geological Survey of New Jersey, Bulletin No. 13. (Union Hill, New Jersey: Dispatch Printing Company, 1915)

- ↑ Archaeology of Warren and Hunterdon counties Geological Survey of New Jersey, Bulletin No. 18. (Trenton, N.J., MacCrellish and Quigley co., state printers, 1917).

- ↑ Chambers, Theodore Frelinghuysen. The early Germans of New Jersey: Their History, Churches, and Genealogies. (Dover, New Jersey, Dover Printing Company, 1895), passim.

- ↑ Schaeffer, Casper, M.D. and Johnson, William M. Memoirs and Reminiscences: Together with Sketches of the Early History of Sussex County, New Jersey. (Hackensack, New Jersey: Privately Printed, 1907). 42–43, 46–47

- ↑ Chambers, op. cit., passim.

- ↑ Viet, Richard F. "John Solomon Teetzel and the Anglo-German Gravestone Carving Tradition of 18th century Northwestern New Jersey" in Markers XVII (Richard E. Meyer, ed.), Journal of the Association for Gravestone Studies, XVII: 124–161 (2000).

- ↑ Schaeffer, Casper, M.D. and Johnson, William M. Memoirs and Reminiscences: Together with Sketches of the Early History of Sussex County, New Jersey. (Hackensack, New Jersey: Privately Printed, 1907). passim.

- 1 2 3 4 Snell, op. cit., passim.

- ↑ Armstrong, William C. Pioneer Families of Northwestern New Jersey (Lambertville, New Jersey: Hunterdon House, 1979), passim

- ↑ Stickney, Charles E. Old Sussex County families of the Minisink Region from articles in the Wantage Recorder (compiled by Virginia Alleman Brown) (Washington, N.J. : Genealogical Researchers, 1988), passim.

- ↑ Wintermute, Jacob Perry. Wintermute Family History. (Columbus, Ohio: Champlin Press, 1900)

- ↑ Wintermute, Leonard. Windemuth Family Heritage. (Baltimore, Maryland: Gateway Press, 1996).

- ↑ Schaeffer and Johnson. op. cit., 33.

- ↑ Military Trail at Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area website, no further authorship information given, accessed October 29, 2006.

- 1 2 Schaeffer and Johnson, loc. cit.

- ↑ Branchville, New Jersey - History, no further authorship information given, accessed October 29, 2006.

- ↑ NJ DEP Attains Settlement Over Water Pollution Violations affecting Paulinskill River (Press Release) at NJDEP website, no further authorship information given, accessed October 29, 2006.

- ↑ "Defend New Jersey's Waters Release List of Top 30 Waterways To Save" in Jersey Coast Anglers Association Newsletter, January 2002

- ↑ New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection: Division of Fish and Wildlife: Amphibians of New Jersey, no further authorship information given, accessed December 20, 2006.

- ↑ "Branchville Sewer Plant May Still Be Built" by Jamie Goldenbaum in New Jersey Herald (April 16, 2002)

- ↑ Cunningham, John T. Railroad Wonder: The Lackawanna Cut-Off (Newark, New Jersey: Newark Sunday News, 1961). NO ISBN

- ↑ Richman, Steven M. The Bridges Of New Jersey: Portraits Of Garden State Crossings (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2005). ISBN 0-8135-3510-7

- ↑ "Touring the Lackawanna Cut-Off" by Don Barnicle and Paula Williams in Skylands Magazine, accessed October 29, 2006.

- ↑ History and Heritage of Civil Engineering: "Tunkhannock Viaduct" at the American Society of Civil Engineers website (ASCE.org), accessed October 29, 2006.

- ↑ Lackawanna Cutoff Project, New Jersey Transit, (www.NJTransit.com), no further authorship information given, (April 2005), accessed October 29, 2006. Archived November 13, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Weird New Jersey Magazine, 2001 Weekly Story Archives, by "Myke L.", no further authorship information given, accessed October 29, 2006. Archived May 17, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Trout Fishing in New Jersey - The Good 'Ole Days are Now!" by Jim Sciascia at New Jersey Division of Fish & Wildlife website, accessed October 29, 2006.

- ↑ Music to a Hare's Ears by Henry Bell in Skylands Magazine, accessed October 29, 2006.

- ↑ Cummings, Warren D. Sussex County: A History (Newton, New Jersey: Newton Rotary Club, 1964). transcribed http://archiver.rootsweb.com/th/read/NJSUSSEX/2002-09/1032918263, accessed October 26, 2006.

- ↑ Fishing for Shad on the Delaware at Delaware River Recreation, no further authorship information given, accessed October 29, 2006.

- ↑ Swartswood State Park, official website, no further authorship information given, accessed December 20, 2006

- 1 2 Worthington State Forest, official website, no further authorship information given, accessed December 20, 2006

- ↑ National Park Service: Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area, official website, no further authorship information given, accessed December 20, 2006

- ↑ Stokes State Forest, official website, no further authorship information given, accessed December 20, 2006

- ↑ Schaeffer and Johnson, op. cit., 45 ff.

- ↑ State Acquisitions Current Projects, Green Acres Program, NJ Department of Environmental Protection no further authorship information given, accessed August 24, 2006. Archived August 27, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Preserved Farmland in Sussex County (NJ), spreadsheet from the County of Sussex (New Jersey) no further authorship information given, accessed October 30, 2006.

- ↑ Preserved Farms in Warren County Hit 100 (2004 Press Release) Warren County (NJ), no further authorship information given, accessed October 30, 2006.

- ↑ New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection: Wildlife Management Areas, no further authorship information given, accessed December 20, 2006.

- ↑ New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection: Division of Fish and Wildlife: Small Game Hunting in New Jersey, no further authorship information given, accessed December 20, 2006.

- ↑ New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection: Division of Fish and Wildlife: Mammals of New Jersey, no further authorship information given, accessed December 20, 2006.

- ↑ New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection: Division of Fish and Wildlife: Reptiles of New Jersey, no further authorship information given, accessed December 20, 2006.

- ↑ Paulinskill Valley Trail at Rails-to-Trail Conservancy, no further authorship information given, accessed August 24, 2006. Archived September 9, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection: Division of Fish and Wildlife: Birds of New Jersey, no further authorship information given, accessed December 20, 2006.

- ↑ Letter from Kenton Kilmer to Aline Kilmer (addressed to c/o Bob Holliday), November 18, 1929. quoted in Hillis, John. Joyce Kilmer: A Bio-Bibliography. Master of Science (Library Science) Thesis. Catholic University of America. (Washington, DC: 1962). NO ISBN.

- ↑ Friday the 13th Filming Locations, no further authorship information given, accessed December 16, 2006.

- ↑ Gael Mooney on Finkelstein, accessed December 21, 2006.

- ↑ "Louis Finkelstein: The Late Pastels in the Context of His Artistic Thinking" at Lori Bookstein Fine Art, accessed December 21, 2006.

Books and printed materials

- Armstrong, William C. Pioneer Families of Northwestern New Jersey (Lambertville, New Jersey: Hunterdon House, 1979). NO ISBN (Privately printed). Reprinted version.

- Cawley, James S. and Cawley, Margaret. Exploring the Little Rivers of New Jersey (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1942, 1961, 1971, 1993). ISBN 0-8135-0684-0

- Chambers, Theodore Frelinghuysen. The early Germans of New Jersey: Their History, Churches, and Genealogies (Dover, New Jersey, Dover Printing Company, 1895). NO ISBN (Pre-1964)

- Cummings, Warren D. Sussex County: A History (Newton, New Jersey: Newton Rotary Club, 1964). NO ISBN (Privately printed).

- Cunningham, John T. Railroad Wonder: The Lackawanna Cut-Off (Newark, New Jersey: Newark Sunday News, 1961). NO ISBN (Pre-1964).

- Documents Relating to the Colonial, Revolutionary and Post-Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey [Title Varies]. Archives of the State of New Jersey, 1st-2nd series. 47 volumes. (Newark, New Jersey: 1880–1949). NO ISBN (pre-1964)

- Gleason, June Benore. Historical Paulinskill Valley, New Jersey: Blairstown's neighbors. (Blairstown, New Jersey: Blairstown Press, 1949). NO ISBN (Pre-1964)

- Honeyman, A. Van Doren (ed.). Northwestern New Jersey—A History of Somerset, Morris, Hunterdon, Warren, and Sussex Counties Volume 1. (Lewis Historical Publishing Co., New York, 1927). NO ISBN (pre-1964)

- Richman, Steven M. The Bridges Of New Jersey: Portraits Of Garden State Crossings. (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2005). ISBN 0-8135-3510-7

- Schaeffer, Casper M.D. (and Johnson, William M.). Memoirs and Reminiscences: Together with Sketches of the Early History of Sussex County, New Jersey. (Hackensack, New Jersey: Privately Printed, 1907). NO ISBN (Pre-1964)

- Schrabisch, Max. Indian habitations in Sussex County, New Jersey Geological Survey of New Jersey, Bulletin No. 13. (Union Hill, New Jersey: Dispatch Printing Company, 1915). NO ISBN (Pre-1964)

- Schrabisch, Max. Archaeology of Warren and Hunterdon counties Geological Survey of New Jersey, Bulletin No. 18. (Trenton, N.J., MacCrellish and Quigley co., state printers, 1917). NO ISBN (Pre-1964)

- Snell, James P. History of Sussex and Warren Counties, New Jersey, With Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of Its Prominent Men and Pioneers. (Philadelphia: Everts & Peck, 1881). NO ISBN (Pre-1964)

- Stickney, Charles E. Old Sussex County families of the Minisink Region from articles in the Wantage Recorder (compiled by Virginia Alleman Brown) (Washington, N.J. : Genealogical Researchers, 1988). NO ISBN (Privately printed).

- Viet, Richard F. "John Solomon Teetzel and the Anglo-German Gravestone Carving Tradition of 18th century Northwestern New Jersey" in Markers XVII (Richard E. Meyer, ed.), Journal of the Association for Gravestone Studies, XVII: 124–161 (2000).

- Wintermute, Jacob Perry. Wintermute Family History. (Columbus, Ohio: Champlin Press, 1900). NO ISBN. [Reprinted: Salem, Massachusetts: Higginson Book Company, NO ISBN] (Pre-1964)

- Wintermute, Leonard. Windemuth Family Heritage. (Baltimore, Maryland: Gateway Press, 1996). NO ISBN (Privately printed).

Maps and atlases

- Map of Jonathan Hampton (1758) in the collection of the New Jersey Historical Society, Newark, New Jersey.

- Hopkins, Griffith Morgan. Map of Sussex County, New Jersey. (1860) [Reprinted by the Sussex County Historical Society: Netcong, New Jersey: Esposito (Jostens), 2004.]

- Beers, Frederick W. County Atlas of Warren, New Jersey: From actual surveys by and under the direction of F. W. Beers (New York: F.W. Beers & Co. 1874). [Reprinted by Warren County Historical Society: Harmony, New Jersey: Harmony Press, 1994].

- Hagstrom Morris/Sussex/Warren counties atlas (Maspeth, New York: Hagstrom Map Company, Inc. 2004).

- United States Geological Survey topographical map "Newton East" and "Newton West" (New Jersey).

External links

- Paulinskill Valley Trail Committee

- Map of The Paulinskill

- U.S. Geological Survey: NJ stream flow-gauging stations