Representative peer

|

| Part of a series on |

| Peerage |

|---|

|

Types |

|

Divisions |

|

History |

| House of Lords |

|

In the United Kingdom, representative peers were those peers elected by the members of the Peerage of Scotland and the Peerage of Ireland to sit in the British House of Lords. Until 1999, all members of the Peerage of England held the right to sit in the House of Lords; they did not elect a limited group of representatives. All peers who were created after 1707 as Peers of Great Britain and after 1801 as Peers of the United Kingdom held the same right to sit in the House of Lords.

Representative peers were introduced in 1707, when the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of Scotland were united into the Kingdom of Great Britain. At the time, there were 168 English and 154 Scottish peers.[1] The English peers feared that the House of Lords would be swamped by the Scottish element, and consequently the election of a small number of representative peers to represent Scotland was negotiated.[1] A similar arrangement was adopted when the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland merged into the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in January 1801.

Scotland was allowed to elect sixteen representative peers, while Ireland could elect twenty-eight.[2] Those chosen by Scotland sat for a single term, and following each dissolution new Scottish peers were elected. In contrast, Irish representative peers sat for life. Elections for Irish peers ceased when the Irish Free State came into existence as a Dominion in December 1922. However, already-elected Irish peers continued to be entitled to sit until their death. Elections for Scottish peers ended in 1963, when all Scottish peers obtained the right to sit in the House of Lords.

Under the 1999 House of Lords Act, a new form of representative peer was introduced to allow some hereditary peers to stay in the House of Lords.[3]

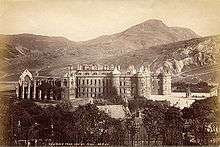

Scotland

Under articles XXII and XXIII of the Act of Union of 1707, Scottish peers were entitled to elect sixteen representative peers to the House of Lords.[4][5] Each served for one Parliament or a maximum of seven years, but could be re-elected during future Parliaments. Upon the summons of a new Parliament, the Sovereign would issue a proclamation summoning Scottish peers to the Palace of Holyroodhouse. The elections were held in the Great Gallery, a large room decorated by eighty-nine of Jacob de Wet's portraits of Scottish monarchs, from Fergus Mór to Charles II. The Lord Clerk Register would read out the Peerage Roll as indicates his presence when called. The Roll was then re–read, with each peer responding by publicly announcing his votes and the return being sent to the clerk of the crown at London.[6] The same procedure was used whenever a vacancy arose.[7]

The block voting system was used, with each peer casting as many votes as there were seats to be filled. The system, however, permitted the party with the greatest number of peers, normally the Conservatives, to procure a disproportionate number of seats, with opposing parties sometimes being left entirely unrepresented. The Lord Clerk Register was responsible for tallying the votes. The return issued by the Lord Clerk Register was sufficient evidence to admit the representative peers to Parliament; however, unlike other peers, Scottish representatives did not receive writs of summons.[8] The position and rights of Scottish peers in relation to the House of Lords remained unclear during most of the eighteenth century. In 1711, The 4th Duke of Hamilton, a peer of Scotland, was made Duke of Brandon in the Peerage of Great Britain. When he sought to sit in the House of Lords, he was denied admittance, the Lords ruling that a peer of Scotland could not sit in the House of Lords unless he was a representative peer, even if he also held a British peerage dignity.[9] They reasoned that the Act of Union 1707 had established the number of Scots peers in the House of Lords at no more and no less than sixteen.[10] In 1782, however, the House of Lords reversed the decision,[9] holding that the Crown could admit anyone it pleases to the House of Lords, whether a Scottish peer or not, subject only to qualifications such as being of full age.[10]

Under the Peerage Act 1963, all Scottish peers procured the right to sit in the House of Lords, and the system of electing representative peers was abolished.[11] Scottish as well as British and English hereditary peers lost their automatic right to sit in the Upper House with the passage of the House of Lords Act 1999. During the debate on the House of Lords Bill, a question arose as to whether the proposal would violate the Treaty of Union.[12] In suggesting that the Bill did indeed violate the Articles of Union, it was submitted that, prior to Union, the Estates of Parliament, Scotland's old, pre-Union parliament, was entitled to impose conditions, and that one fundamental condition was a guarantee of representation of Scotland in both Houses of Parliament at Westminster. It was implied, furthermore, that the Peerage Act of 1963 did not violate the requirement of Scottish representation, set out in the Article XXII of the Treaty of Union, by allowing all Scottish peers to sit in the House of Lords: as long as a minimum of sixteen seats were reserved for Scotland, the principles of the Article would be upheld.[12][13] It was further argued that the only way to rescind the requirement of Article XXII would be to dissolve the Union between England and Scotland,[13] which the House of Lords Bill did not seek to do.[11]

Counsel for the Government held a different view. It was noted that the Peerage Act 1963 explicitly repealed the portions of the Articles of Union relating to elections of representative peers, and that no parliamentary commentators had raised doubts as to the validity of those repeals. As Article XXII had been, or at least purportedly, repealed, there was nothing specific in the Treaty that the bill transgressed. It was further asserted by the Government that Article XXII could be repealed because it had not been entrenched. Examples of entrenched provisions are numerous: England and Scotland were united "forever",[14] the Court of Session was to remain "in all time coming within Scotland as it is now constituted",[15] and the establishment of the Church of Scotland was "effectually and unalterably secured".[16] Article XXII, however, did not include any words of entrenchment, making it "fundamental or unalterable in all time coming".[17]

Further, the Government pointed out that, even if the election of Scottish peers were entrenched, Parliament could amend the provision under the doctrine of Parliamentary sovereignty. Though the position of the Church of Scotland was "unalterably" secured, the Universities (Scotland) Act 1853 repealed the requirement that professors declare their faith before assuming a position.[18] In Ireland, the Church of Ireland was entirely disestablished in 1869,[19][20] though the Articles of Union with Ireland had clearly entrenched the establishment of that body. In December 1922, the Union with most of Ireland was dissolved upon the creation of the Irish Free State,[21] though Great Britain and all of Ireland were supposedly united "forever." It was therefore suggested that Parliament could, if it pleased, repeal an Article of Union as well amend as any underlying principle.

The Privileges Committee unanimously found that the Articles of Union would not be breached by the House of Lords Bill if it were enacted.[16] The bill did receive Royal Assent, and from 1999, hereditary peers have not had the automatic right to sit in Parliament.[22]

Ireland

Under the Acts of Union in 1800, Irish peers were allowed to elect twenty-eight representative peers, each of whom could serve for life.[2] The Chamber of the Irish House of Lords, located in Parliament House on College Green in central Dublin, housed the first election, attended by the peers or their proxies. The Clerk of the Crown in Ireland was responsible for electoral arrangements; each peer voted by an open and public ballot. The results of the first election were announced by the Clerk of the Crown and published in both The Dublin Gazette and The London Gazette.[23] After the Union, new elections were held whenever vacancies occurred due to the death of any peer. The Lord Chancellor of Great Britain—the presiding officer of the House of Lords—certified the vacancy,[24] while the Lord Chancellor of Ireland directed the Clerk of the Crown to issue ballots to Irish peers. The ballots were returned to the Clerk of the Crown in Ireland, who was responsible for determining the victor.[25]

Ireland was further represented in the House of Lords by four Lords Spiritual, who sat in rotation for terms lasting one session each. At any one time, an Archbishop and three Bishops represented Ireland, with the seats passing according to a fixed rotation, except that those Lords Spiritual who were also elected to serve as representative peers would be omitted.[4][26] The rotation was changed by the Church Temporalities Act of 1833, which merged many dioceses and degraded the archbishoprics of Tuam and Cashel to bishoprics.[27] Following its disestablishment in 1871 by the Irish Church Act 1869, the Church of Ireland ceased to send spiritual representatives to the Lords.[28]

Following the establishment of the Irish Free State in December 1922, Irish peers ceased to elect representatives, although those already elected were allowed to serve for life; the last of the temporal peers, The 4th Earl of Kilmorey (a peer from an Ulster family), died in 1961.[29] Disputes then arose as to whether representative peers could still be elected. The Act establishing the Irish Free State was silent on the matter, although the Irish Free State (Consequential Provisions) Act 1922 had abolished the office of Lord Chancellor of Ireland,[30] whose involvement was required in the election process; the office of Clerk of the Crown had also been abolished in Ireland. Various Irish peers petitioned the House of Lords for a restoration of their right to elect representatives. In 1962, the Joint Committee on House of Lords Reform rejected such plans.[31] In the next year, when the Peerage Act 1963 (which, among other things, gave all peers in the Peerage of Scotland the right to sit in the House of Lords) was being considered, an amendment to similarly allow Irish peers to attend was defeated, ninety to eight. Instead, the new Act gave all Irish peers the right to stand for election to the House of Commons, and to vote at parliamentary elections.[11]

In 1965, the 8th Earl of Antrim (another peer from Ulster) and other Irish peers petitioned the House of Lords, arguing that the right to elect representative peers had never been formally abolished. The House of Lords ruled against the Irish peers. Lord Reid, a Lord of Appeal in Ordinary, based his ruling on the Act of Union, which stated that representative peers sat "on the part of Ireland."[31] He reasoned that, since the island had been divided into the Irish Free State and Northern Ireland, there was no such political entity called "Ireland" which the representative peers could be said to represent. Lord Reid wrote, "A statutory provision is impliedly repealed if a later enactment brings to an end a state of things the continuance of which is essential for its operation."[32] In contrast, Lord Wilberforce, another Lord of Appeal in Ordinary, disagreed that a major enactment such as the Act of Union could be repealed by implication.[31] He argued instead on the basis that the Irish Free State Act 1921—which was silent on the election of representative peers—abolished the posts of Lord Chancellor of Ireland and Clerk of the Crown in Ireland. The Lord Chancellor of Ireland was responsible for calling elections of representative peers, and the Clerk of the Crown in Ireland was responsible for sending peers their ballots. Since these offices had been abolished; Lord Wilberforce argued against any mechanism by which Irish peers could be elected. Here too, the petitioners lost.[31]

The petitioners failed to raise the status of Northern Ireland as part of the United Kingdom. Burke's Peerage & Baronetage suggests that if this fact had been foremost, Lord Wilberforce's arguments relating to the removal of the electoral mechanism for the election could be rebutted, as the Lord Chancellor of Ireland and the Clerk of the Crown in Ireland did have replacements in Northern Ireland. The reason for excluding the arguments relating to Northern Ireland from the petition "was that leading counsel for the petitioning Irish peers was convinced that the members of the Committee for Privileges were with him on what he considered was his best argument and did not want to alienate them by introducing another point."[31] To prevent further appeals on the matter, Parliament repealed, as a part of the Statute Law (Repeals) Act 1971, the sections of the Acts of Union relating to the election of Irish representative peers.[31]

House of Commons

After the Union of England and Scotland in 1707, Scottish peers, including those who did not sit as representative peers, were excluded from the House of Commons.[33] Irish peers were more favoured and not subjected to the same restrictions. Irish members not nominated as representative peers were allowed serve in Parliament as a representative of a constituency in Great Britain, although not in Ireland,[34] provided they gave up their privileges as a peer.[35] Lord Curzon, for example, specifically requested an Irish peerage so he would not be debarred from sitting in the House of Commons.

The Peerage Act 1963 allowed all Scottish peers to sit in the House of Lords;[36] it also permitted all Irish peers to sit in the House of Commons for any constituency in the United Kingdom, as well as to vote in parliamentary elections, without being deprived of the remaining privileges of peerage.[11]

Hereditary "representative peers"

During the passage of the House of Lords Bill in 1999, controversy surrounding House of Lords reform remained,[37] and the Bill was conceived as a first stage of Lords reform.[38] The "Weatherill" amendment—so called since it was proposed by former House of Commons Speaker Bernard Weatherill—provided for a number of hereditary peers to remain as members of the House of Lords, during the first stage of Lords reform.[39] It could then be reviewed during the next stage of the reform, when the system of appointed life peerages came under examination. In exchange for the House not delaying the passage of the Bill into law, the Government agreed to this amendment, and it then became part of the House of Lords Act 1999, and 92 hereditary peers were allowed to remain.[40]

The ninety-two peers are made up of three separate groups. Fifteen 'office-holders' comprise Deputy Speakers and Deputy Chairmen, and are elected by the House, while seventy-five party and Crossbench members are elected by their own party or group.[3] In addition, there are two royal appointments: the Lord Great Chamberlain,[3] currently the Marquess of Cholmondeley, is appointed as the Queen's representative in Parliament, while the post of Earl Marshal[3] remains purely hereditary; the office has been held since 1672 by the Dukes of Norfolk and is responsible for ceremonies such as the State Opening of Parliament.[41]

Notes

- 1 2 Lord Nicholls of Birkenhead. "Opinions of the Committee". Select Committee on Privileges Second Report. Retrieved 7 April 2007.

- 1 2 May, Erskine (1862). The Constitutional History of England since the Accession of George III 1760–1860. Boston: Crosby & Nichols. p. 228.

- 1 2 3 4 "Membership: Types of Member" (PDF). House of Lords. 2009. p. 2. Retrieved 31 January 2013.

- 1 2 May, Thomas Erskine (1851). A practical treatise on the law, privileges, proceedings and usage of Parliament. Butterworths. pp. 6–8, 15. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- ↑ Price, Jacob M (December 1961). "The Sixteen Peers of Scotland: An Account of the Elections of the Representative Peers of Scotland, 1707–1959 by James Fergusson". The Journal of Modern History. 33 (4): 439. doi:10.1086/238935.

- ↑ Connell, Arthur (1827). A Treatise on the Election Laws in Scotland: To which is Added an Historical Inquiry Concerning the Municipal Constitutions of Towns and Boroughs. pp. 17–8.

- ↑ Wight, Alexander (1806). "The Scottish Peers". An Inquiry into the Rise and Progress of Parliament, Chiefly in Scotland. 1. W. Creech & J. Murray. p. 127.

- ↑ "House of Lords Hansard for 29 Apr 1999 (pt 16)". House of Lords Hansard. Retrieved 7 April 2007.

- 1 2 Debrett, John (1839). Debrett's Peerage of England, Scotland, and Ireland. London: J. G. & F. Rivington. p. 358.

- 1 2 Connell, Arthur (1827). A treatise on the election laws in Scotland. Edinburgh: William Blackwood. pp. 9–11. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 "Peerage Act 1963". The Committee Office, House of Lords. Retrieved 7 April 2007.

- 1 2 Lord Slynn Hadley. "Select Committee on Privileges Second Report". The Committee Office, House of Lords. Retrieved 7 April 2007.

- 1 2 Richard S. Keen. "Case for the Lord Gray". The Committee Office, House of Lords. Retrieved 23 February 2010.

- ↑ "Treaty of Union 1707". The Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707. School of History at the University of St Andrews. 1706. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- ↑ "Union With England Act 1707". The Committee Office, House of Lords. Retrieved 7 April 2007.

- 1 2 "Appendix 3 'Case for Her Majesty's Government'". Select Committee on Privileges Second Report. Retrieved 7 April 2007.

- ↑ Hector L. MacQueen, Scott Wortley (September 1998). "House of Lords reform and the Treaty of Union". University of Edinburgh. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ↑ "Union with Scotland Act 1706". Select Committee on Privileges Second Report. The Committee Office, House of Lords. Retrieved 7 April 2007.

- ↑ Hunt, Jocelyn (2003). Britain, 1846–1919. Routledge. p. 225.

- ↑ Evan, Anna Laura (1929). The disestablishment of the Church of Ireland in 1869. Lancaster: James & Naomi.

- ↑ "Early Irish Law and Brehon law". Courts Service of Ireland. Retrieved 7 April 2007.

- ↑ "Different types of Lords". About Parliament. Parliament of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ↑ Finnelly, William (1830). The Law and Practice of Elections in England, Scotland, and Ireland. London: A. Maxwell. pp. 161–3.

- ↑ Finnelly, (1830), p 164

- ↑ May, A practical treatise ... of Parliament (1851), p 169

- ↑ Malcomson (2002), p. 325

- ↑ "A Brief History - Reformation (1536) - Disestablishment (1871)". Diocese of Dublin and Glendalough. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- ↑ "A Brief History - Disestablishment (1871) - Modern Times". Diocese of Dublin and Glendalough. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ↑ Gadd, R.P. "A short account of the peerage of Ireland". The Heraldry Society. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- ↑ Brigid Hadfield (1998). "The Northern Ireland Act 1998 and the Act of Union". BBC NI. Retrieved 7 April 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Lysaght, Charles (1999). "The Irish Peers and the House of Lords". 106th Edition. Burke's Peerage & Baronetage. Archived from the original on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 7 April 2007.

- ↑ Brigid Hadfield (1998). "The Belfast Agreement, Sovereignty and the State of the Union". BBC NI. Retrieved 7 April 2007.

- ↑ Stephenson, Charles (2006). The Admiral's Secret Weapon: Lord Dundonald And the Origins of Chemical Warfare. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. p. 35. ISBN 1-84383-280-1.

- ↑ Ruvigny, Melville H. (1910). The Nobilities of Europe. London: Melville and Company. p. 1. ISBN 1-4021-8561-8.

- ↑ "Act of Union (Ireland) 1800 (c.38)". The UK Statute Law Database. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- ↑ "Legislation affecting the House of Lords: Legislation affecting the House of Lords". Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ↑ "Hansard, Vol 604 No 127 Cols 1399–1422". 27 July 1999. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ↑ "HC Hansard, Vol 321 Col 874". 2 December 1998. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ↑ Michael White and Lucy Ward (12 May 1999). "Suspicious peers back reform". The Guardian.

- ↑ "Annual Report and Accounts 1999–2000". United Kingdom Parliament. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ↑ "Earl Marshal". Official Royal posts. The Royal Household. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

Sources

- Farnborough, Thomas. Erskine. May, 1st Baron. (1863) Constitutional History of England since the Accession of George the Third. Volume 1 Boston: Crosby and Nichols.

- Lysaght, Charles. (1999). "The Irish Peers and the House of Lords - The Final Chapter." Burke's Peerage & Baronetage. 106th ed. London: Fitzroy Dearborn.

- Malcomson, A.P.W. "The Irish Peerage and the Act of Union, 1800–1971". Cambridge University Press, 9 April 2002.

- Documents on Irish Foreign Policy Series: Anglo-Irish Treaty: Text of. Anglo-Irish Treaty, 6 December 1921. The National Archives of Ireland. Retrieved 2007-04-07

- Briefing Paper: Membership of House of Lords (pdf). House of Lords, 2009. Retrieved 2013-01-31

- Peerage (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th ed. London: Cambridge University Press.

- Privileges - First Report. House of Lords, 18 October 1999. Retrieved 2007-04-07