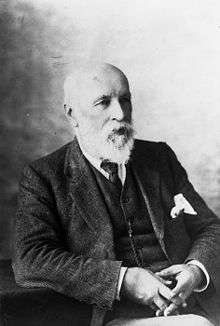

Percy Smith (ethnologist)

Stephenson Percy Smith (11 June 1840 – 19 April 1922) was a New Zealand ethnologist and surveyor. He founded The Polynesian Society.

Biography

Early life and career as a surveyor

Percy Smith (as he was known) was born in Beccles, Suffolk, the eldest son of Hannah Hursthouse and John Stephenson Smith, a merchant and later a civil servant. Smith emigrated to New Zealand with his family in February 1850. Percy Smith attended school at New Plymouth and later Omata, leaving to help on the family farm in 1854. Interested in the natural world and the landscape of the Taranaki Region, Smith took lessons in painting from John Gully, a landscape artist. In 1855, aged 14, he joined the provincial survey department, helping to survey the land around New Plymouth, spending long periods in the bush and coming into frequent contact with Māori. Following two years of training, he was made assistant surveyor. While still in his teens, he began a series of expeditions in his spare time, joining a party to scale Mount Taranaki in 1857, for example, and undertaking a journey in 1858 up the Mōkau River to Taupo, Lakes Rotomahana and Tarawera, the Tongariro-Ruapehu area, returning via Rangitikei and Wanganui. This expedition was over 1000 kilometres (600 miles) on foot, horse, and canoe.

During his service in the local militia, Smith also witnessed at first hand the conflict leading up to the Taranaki wars. In March 1858 he saw the fighting at Waitara, where he was employed to make sketches of the stockades. In 1859 was transferred to the Auckland district where he worked with the Land Purchase Department, surveying newly acquired government land in the Kaipara and Northern Wairoa. In April 1860 he was instructed to return at once to Kaipara, where he acted as an interpreter and intermediary to persuade Ngāti Whātua to help in the defence of Auckland against a rumoured attack from the Waikato tribes. Smith was then employed in laying out the boundaries of blocks at Coromandel and in the survey of military settlements in the Waikato.

Smith married Mary Anne Crompton on 23 April 1863. They remained in Auckland until 1865, when he was transferred back to Taranaki as district surveyor. There his main duties were the survey of lands confiscated from the Māori. In the following decade, he surveyed territories in various parts of New Zealand. In 1868 he was undertaking a survey of Pitt Islands in the Chathams at the time when Te Kooti escaped on the Rifleman to Poverty Bay. Smith was appointed the first geodesical surveyor and chief surveyor of the provincial district of Auckland in the department of the surveyor general in 1877 and assistant surveyor-general in 1882. Immediately after the eruption of Mount Tarawera in 1886, he made visits to the region and reported his findings in The Eruption of Tarawera (1886).

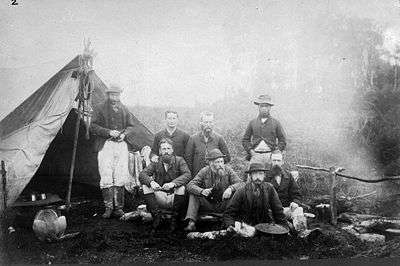

In 1887, he joined an expedition to the Kermadec Islands to confirm New Zealand possession and to report on the group, which he did in The Kermadec Islands: Their Capabilities and Extent (1887). His career as a surveyor reached its peak when he was appointed as Surveyor-General of New Zealand in January 1889.

Work as an ethnologist

In the course of his surveying expeditions, Smith took advantage of any opportunity to collect and record information on the traditional history and culture of the Māori, material which would later form the foundation for his work as a Polynesian scholar. Not until he retired from the civil service was he able to give his unrestricted attention to these studies. By now a recognised scholar of the Māori language, Percy Smith was regarded by his contemporaries as a leading Pākehā authority on Māori history and traditions. To provide a focal point for ethnological research in New Zealand, he called a meeting in Wellington in January 1892 to establish the Polynesian Society, becoming its first secretary and treasurer. He was also the first co-editor of the Journal of the Polynesian Society, alongside Edward Tregear. Smith was to be the main contributor to the Journal until his death 30 years later, during which time he also published a lengthy series of studies of Māori history. In 1897 undertook a six-month tour of the Pacific, promoting the Polynesian Society and gathering material in support of his thesis regarding the history of the Polynesians. The tour was 'a seminal event' in Smith's ethnological career and he gained access to a number of manuscripts from Rarotonga and other places. Using these manuscripts gathered in Polynesia and other sources from New Zealand, Smith constructed an elaborate history of the Polynesians from a purported Aryan origin in India,[3] a history originally published in volumes 7 and 8 (1898–1899) of the Journal of the Polynesian Society (Walker et al. 2000:viii-ix).[4] This study was republished in book form as Hawaiki, the Original Home of the Maori (1921), later reprinted in a number of editions. Hawaiki had a tremendous impact on the popular view of Māori history, becoming the authorised version until relatively recent times when its authenticity came under scrutiny in the writings of David Simmons (1976) and M.P.K. Sorrensen (1979).

Latter years

Smith retired in October 1900, and from that time onwards he dedicated himself increasingly to his research, although in 1902 he was appointed as Government Resident in Niue Island after its annexation by New Zealand. He spent five months on Niue, arranging the administrative and legal systems and drafting the constitution. At the same time, however, he gathered material on the ethnology and language of the island for two further publications. In 1904 appeared one of his most enduring studies, The Wars of the Northern Against the Southern Tribes, which was revised as The Maori Wars of the Nineteenth Century.

A few years later, Smith published History and Traditions of the Maoris of the West Coast, North Island (1910), a monumental study of the traditional history of the regions with which he was best acquainted.

He died at his home in New Plymouth, on 19 April 1922.

Legacy

The assessment of Smith's contribution, unreservedly generous at his death, has changed somewhat in recent decades. In 1966, The Encyclopaedia of New Zealand was generally positive, with some qualification. "His careful recording of traditional material, cross checked as far as possible by varying tribal histories, left an invaluable contribution... Although they can now be amplified or corrected on points of detail, the structure is substantially unchanged. In his studies on Maori origins he was more uncritical and framed hypotheses on what now seems slender linguistic and traditional evidence. The nevertheless high standard, for the period, of his own work and its publication provided a touchstone for later amplification which is being revised only today by more developed archaeological and critical techniques" (Bagnall 1966:266).

Smith's biography (first published in 1993) in the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography is more forthright, stating that "In some areas, particularly his account of the origins of the Maori and their arrival in New Zealand, Smith's interpretation has not survived the light cast on it by later historical and archaeological research. Scholars have criticised Smith's use of his source materials and his editing of Maori traditions for publication.... Smith's careers in surveying and ethnology were characterised by hard work and dedication, and he received recognition for both in his lifetime. Although it is now generally accepted that much of his work on the Maori is unreliable, his research nevertheless provided a basis for the development of professional ethnology in New Zealand. As a successful civil servant and respected scholar he was perhaps one of New Zealand's most prolific intellectuals of the late nineteenth century, and was a major contributor to the scientific debate over the origins and nature of the Maori" (G.M. Byrnes 2006).

Historian Rāwiri Taonui, writing in 2006 for the website Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, accuses Smith of falsification: "The Great Fleet theory was the result of a collaboration between the 19th-century ethnologist S. Percy Smith and the Māori scholar Hoani Te Whatahoro Jury. Smith obtained details about places in Rarotonga and Tahiti during a visit in 1897, while Jury provided information about Māori canoes in New Zealand. Smith then 'cut and pasted' his material, combining several oral traditions into new ones. Their joint work was published in two books, in which Jury and Smith falsely attributed much of their information to two 19th-century tohunga, Moihi Te Mātorohanga and Nēpia Pōhūhū" (Taonui 2006).

Notes

- ↑ Photograph by kind permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand, Reference number: 1/2-005564-F.

- ↑ Photograph by kind permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand, Reference number: 1/2-061056-F.

- ↑ Smith used the methods pioneered by Abraham Fornander to derive a similar history for the Hawaiians.

- ↑ In the same period, Smith published The Peopling of the North, the Maori history of the Ngāti Whātua tribe, (1898).

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Percy Smith (ethnologist). |

- teara.govt.nz, A. G. Bagnall, 'Smith, Stephenson Percy (1840–1922)' in A. H. McLintock (editor), Encyclopaedia of New Zealand, 3 Volumes. (Government Printer: Wellington), 1966, III:265–266.

- dnzb.govt.nz, G. M. Byrnes, 'Smith, Stephenson Percy 1840 – 1922'. Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, updated 7 April 2006. URL: *D.R. Simmons, The Great New Zealand Myth: a study of the discovery and origin traditions of the Maori (Reed: Wellington) 1976.

- M. P. K. Sorrensen, Maori Origins and Migrations. The genesis of some Pakeha myths (Auckland University Press: Auckland), 1979.

- teara.govt.nz/NewZealanders/MaoriNewZealanders/CanoeTraditions/en, R. Taonui. 'Canoe traditions', Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 3 April 2006. URL:

- R. Walter, R. Moeka'a, History and Traditions of Rarotonga by Te Ariki Tara 'Are, (Auckland: The Polynesian Society) 2000.