Perim

Perim (Arabic: بريم [Barīm]), also called Mayyun in Arabic, is a volcanic island in the Strait of Mandeb at the south entrance into the Red Sea, off the south-west coast of Yemen and belonging to Yemen. The island of Perim divides the strait of Mandeb into two channels.

The island was occupied by Great Britain from 1857 to 1967.

Etymology

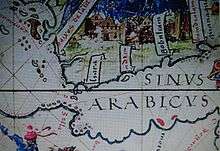

Perim is called the island of Diodorus (Diodori insula) by Pliny the Elder[1] and by the author of the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea.[2] Perim possibly derives from the Arab term Barim (chain) associated with the history of the Straits and one of its Arab names, the other Arab name being Mayyun. The Portuguese called it Majun or Meho (from Mayyun), although Albuquerque had solemnly named the island Vera Cruz in 1513. On many British and French maps of the 17th and 18th century the island is called Babelmandel, as the Straits are. Some early 19th century navigation guides still call it the island of Bab-el-Mandeb although they may mention that it is also called Perim.[3] By the time the British permanently occupied the island in 1857, the name Perim had come into general usage.

Geography

Perim island is an eroded fragment of the southwest flank of a late Miocene volcano whose center was on the southwesternmost tip of Arabia. The volcano is the westernmost of the east-west line of six central vent volcanoes (the Aden line) that extends 200 km (125 mi) along the coast of Arabia from Perim to Aden. It is believed that the volcanism is related to an eastward-propagating rift produced before the most recent stage of sea-floor spreading in the Gulf of Aden.[4]

Perim is crab-shaped, 5.63 km (3.5 mi) long and 2.85 km (1.77 mi) wide.[5] It has a surface area of 13 km2 (5.0 sq mi) and rises to an altitude of 65 m (213 ft). Perim encloses a deep and comparatively large natural harbour on the southwestern coast. The fishing village of Mayyun is located at the bottom of the bay.

The island divides the 32 km (20 mi) wide Bab-el-Mandeb into two: the Large Strait, with an average width of 17 km (11 mi), and the Small Strait, varying from 5 km to 2.5 km (3 mi to 1.5 mi) in width. The Large Strait is generally deep water varying from about 100 fathoms or more in the middle channel to about 3 to 6 fathoms close to the coastal reefs. The depth of the Small Strait varies from 12 to 15 ½ fathoms and is free from navigational changes in the fairway but strong and irregular tidal streams make navigation hazardous.[6] There has been frequent shipwrecks in the vicinity of Perim, particularly in the Small Strait.

The absence of fresh water on the island has always been one of the major difficulties impeding permanent settlement. Although there are occasional heavy rains, there may be stretches of eight months or more without rain; the long-term average rainfall (in 1821–1912) was about 60 mm per year.[7] Vegetation is very scarce.

History

The straits of Bab-el-Mandeb were probably witness to the earliest migrations of modern humans (not including other hominins) out of Africa roughly 60,000 years ago. It is presumed that at this time, the oceans were much lower and the straits were much shallower or dry, allowing a series of emigrations along the southern coast of Asia.

Despite its sheltered natural harbour and strategic location at the entrance of the Red Sea, Perim was largely bypassed by history until the middle of the 19th century, in good part because the bare, waterless volcanic island could not easily sustain human and animal life for any length of time. The logistics of continuously bringing in and stocking water on that scorching speck of land did not favor permanent settlement. As a result, only fishermen and pearl divers lived there seasonally, building reed huts with material brought from elsewhere.

In 1513, Albuquerque, as part of the Portuguese bid to seize control of the trade routes to the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf, attacked Aden near the entrance to the Red Sea but failed to capture the fortified city. Having failed in his main objective, he nonetheless sailed for the Red Sea. The Red Sea pilots of those days lived on an island close to Perim and one was secured by sending forward as a decoy an Indian-built ship. The passage of the first Portuguese ship through the Bab-el-Mandeb was the occasion for much ceremony. After having spent some time at the island of Kamaran in preparation for an attack on Jeddah that, due to contrary winds, could not be carried out, the fleet left Kamaran on its return journey. On the way, Perim, which Albuquerque named Vera Cruz, was inspected and pronounced unfit for a fortress due to lack of water.[8]

During the following years, the Portuguese tried several more times to conquer Aden and gain the mastery of the Red Sea, harassing shipping and battling the Egyptian Mamluk, then Ottoman navies, which gradually gained the upper hand. These actions as well as the sending of an annual fleet to blockade the Bab-el-Mandeb and prevent Indian merchant ships from entering the Red Sea most likely involved frequent use of Perim’s natural harbour. By the time the Ottomans captured Aden from its local ruler in 1538, the Red Sea was fast becoming a Turkish lake. The Ottoman fleet remained in firm control of the Red Sea, the Bab-el-Mandeb and Aden until the 1630s when the Turks were expelled from Yemen and the south half of the Red Sea.[9]

A French naval squadron may have used Perim's natural harbor in the course of a punitive expedition against nearby Mocha in 1737.[10] In 1799, the island was briefly occupied by the British East India Company in preparation for the invasion of Egypt.

Perim under British rule

In 1856, seeing in the French-sponsored Suez Canal project a devious trick to promote French power at Britain’s expense, Prime Minister Palmerston agreed to the occupation of Perim as one of many options to counter assumed French political and military ambitions in Egypt and the Red Sea. In December 1856, Lord Elphinstone, the governor of Bombay, wrote to the Resident of Aden that "on the subject of Perim, [..] we have been directed to occupy the island, and that it is the intention of Her Majesty's government that a lighthouse should be built there." He added that since the island had already been taken possession of in the name of the East India Company in 1799, it was considered as a part of the dependencies of India, and therefore no formalities of any kind was necessary. The Resident immediately proceeded to organize a small landing party for the peaceful occupation of the uninhabited island. [11] The actual decision to occupy might have been precipitated by an unfounded report that the French, who were said to have been surveying the area for some time, had dispatched a frigate from Réunion to annex the island.[12][13] The declared reason for the occupation however was the urgent need to erect a lighthouse at the entrance of the notoriously dangerous Bab el Mandeb and indeed, after much bickering about the location and other factors, an 11-meter high lighthouse was finally built and inaugurated on 1 April 1861. This important light was not to prevent the treacherous waters around Perim to continue to claim more than their fair share of vessels wrecked in the Red Sea.[14][15]

Perim was attached to Aden, itself a dependency of the Bombay Presidency, British India. For the next two decades, the only sign of British occupation was the lighthouse and a small detachment from the Aden garrison. Otherwise, the barren waterless island was left to the few fishermen and Somali herders who went there.[16] Occasional proposals by an Aden coaling company to open a branch on the island did not materialize.

Perim’s turn in fortune came with Aden’s slowness in solving a growing problem. While Aden offered the appearance of one of the finest natural harbours in the world, this became less so from the mid-19th century onward when iron and steel-built ships of greater and greater draught were being built. Starting in the 1860s, many of the larger steamers had to stay well off Aden Harbour, making the process of coaling and taking in provisions both time-consuming and hazardous.[17] This deficiency was not to be overcome until dredging and re-dredging projects began in earnest in the early 1890s.[18]

In 1881, a complete outsider, Hinton Spalding of London, was granted permission to start a coaling station on Perim, whose vast and deep inner harbour could accommodate vessels of any draught. With the backing of a number of large ship-owners, including some who had been vociferously complaining about the increasing hurdle of coaling at Aden, he launched the Perim Coal Company (PCC) and on 29 August 1883 the first steamer was coaled in Perim Harbour. This marked the beginning of a struggle between Aden and Perim for the Red Sea coaling business that was to be waged with varying degrees of success and animosity by the two ports until the mid-1930s.[19]

During those 50 years, Perim was to be entirely geared to coaling: the harbour, roads, coolie accommodations, all were laid out for this sole purpose and no other interests or activities were allowed to hinder the coaling. As for Perim’s lack of water, it was no more a drawback than at Aden: both ports supplied water from condensers to the ships, since Aden water, delivered from out of town, was considered too brackish for the purpose. Before long the PCC was also able to grab the lion’s share of the salvage business due to it being very near the most dangerous waters in the area.[20]

In the first decade after World War I, competition from Perim reached a peak to the point that between 1923 and 1927 more coal was being loaded aboard passing steamers than at Aden.[21] However, Perim’s decline came fast upon this crowning success due to its failure to grab a share of the fast-growing oil fuel business which was being quickly cornered by Aden. The older coal-burning steamers were fast being retired from the late 1920s onward and with them went Perim’s fortune.[21] The PCC went bankrupt in 1935 and Perim slipped back into insignificance.

Perim's rare distraction from its coaling activities occurred in 1916 when Turkish forces attempted to seize the island by surprise but were pushed back.

British withdrawal and aftermath

The British presence continued until 1967 when the island became part of the People's Republic of South Yemen. Prior to the handover of Perim to the new Republic, the British government had put forward before the United Nations a proposal for the internationalisation of the island[22][23] as a way to ensure continued security of passage and navigation in the Bab-el-Mandeb. Upon the refusal of the proposal, the British government declared that, “in view of the negative reaction of the United Nations to the proposal for the internationalisation of Perim, the British had consulted the people who had confirmed their wish to remain with South Arabia, accordingly, Perim would be part of the new Republic”.[23]

Soon after independence in November 1967, South Yemen extended its territorial waters to 12 miles, which would include the waters between Perim and the mainland. Despite fears expressed by the British government and others, there was to be no interference with international shipping,[24] until 1971 when the new radical Marxist government of what was now the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY) allowed a group of PFLP guerillas to attack an Israel-bound tanker in the Bab-el-Mandeb from Perim. During the October War, South Yemeni artillery on Perim, along with Egyptian naval units, imposed an undeclared blockade at the southern entrance of the Red Sea. However, after the 1973 blockade, there were to be no further cases of interference with international shipping.[25] The PDRY established close political and military ties with the Soviet Union which resulted in Soviet naval forces gaining access to the former British naval base at Aden as well as to the islands of Perim and Socotra. This strong Soviet military presence faded rapidly after the 1986 military coup in South Yemen and the advent of Perestroika under Mikhail Gorbachev.[26]

Yemen-Djibouti Bridge Project

A $200-billion mega-project for the construction of a transcontinental bridge linking Yemen and Djibouti via Perim Island, the Bridge of the Horns, was announced in 2008 by a Dubai-based company, Al Noor Holding Investments. At around 28.5 kilometres (17.7 mi), it would be one of the longest bridges in the world and its suspension portion the longest. However, following the Dubai financial crisis of 2009, which put a brake to Dubai-sponsored billion-dollar projects of dubious economic value,[27] and the increase of both terrorist and piracy activities in the region, little has been heard of the Bridge of the Horns since the June 2010 announcement that the start of Phase I, the 3.5-km long bridge between the mainland of Yemen and Perim, was delayed until a framework agreement between Djibouti and Yemen was signed.[28]

References

- ↑ http://www.trismegistos.org/geo/authors_georef_list.php?tm=3616

- ↑ Captain, F. M. Hunter, An Account of the British Settlement of Aden in Arabia, London, 1877, p. 191.

- ↑ India Directory, or Directions for Sailing to and from the East Indies,[...], London 1836.

- ↑ Abstract of article "Perim Island, a volcanic remnant at the southern entrance to the Red Sea", by D.I.J. Mallick, Geological Magazine, Vol. 127, Issue 04/July 1990

- ↑ Perim Island: The Last Colonial Outpost

- ↑ Ali A. Hakim, The Middle Eastern States and the Law of the Sea, Manchester University Press, 1979, p. 12.

- ↑ Peter Pickering & Ingleby Jefferson (2012), Rainfall, section of Perim Island - The Last Colonial Outpost. Forum Gallery Aden. Accessed on 2012-07-06.

- ↑ R.S.Whiteway, The Rise of Portuguese Power in India, 1497-1550, London, 1899, pp. 153-157. https://archive.org/details/riseportuguesep00whitgoog

- ↑ R. J. Gavin, Aden under British Rule, 1839-1967, Barnes and Noble, New York, 1975, pp. 15-17.

- ↑ Some British historians reported that the French occupied and even annexed the island in 1737 but a French naval historian found nothing about such an occupation in the logbook of the expedition. Henri Labrousse, Récits de la Mer Rouge et de l'Océan Indien, Paris, Economica, 1992, p. 74.

- ↑ R. L. Playfair, "The true story of the occupation of Perim", in The Asiatic Quarterly Review, London, July–October 1886, p. 149.

- ↑ R. J. Gavin, Aden Under British Rule, 1839–1967, Harper & Row Publishers Inc, New York, 1975, p. 95 (also note 20)

- ↑ Contemporary French archives indicate that neither the French government nor the French navy showed interest in Perim. Nevertheless, the episode gave birth to a Royal Navy urban legend according to which during the frigate's stopover in Aden, the French captain and officials were wined and dined until they were too intoxicated to set sail, giving time to the British to quickly dispatch a vessel to Perim to hoist the British flag. C. R. Low, History of the Indian Navy (1613-1863), Volume 2, p. 385-386.

- ↑ Gavin, pp. 94-95.

- ↑ Peter Pickering & Ingleby Jefferson (2012), Perim Lighthouse, section of Perim Island - The Last Colonial Outpost.

- ↑ Gavin, p. 178.

- ↑ Gavin, pp. 181-182.

- ↑ Gavin, p. 184.

- ↑ Gavin, p. 183.

- ↑ Gavin, p. 181.

- 1 2 Gavin, p. 291.

- ↑ Fred Halliday, Revolution and Foreign Policy, the Case of South Yemen, 1967-1987. Cambridge University Press, 1990, p. 11.

- 1 2 Hakim, pp. 17-18.

- ↑ Hakim, pp. 14-15.

- ↑ Halliday, pp. 175-176

- ↑ Melvin A. Goodman, Gorbachev's Retreat: The Third World, Praeger, 1991, pp. 87-88.

- ↑ The proposed bridge would link two of the poorest and most politically unstable regions of the world: Yemen and the Horn of Africa. The project is totally unsupported by Saudi Arabia and therefore the bridge and the hundreds of kilometers of projected roads through chronically unstable, terrorism-prone Yemen, would lead nowhere.

- ↑ http://basementgeographer.com/bridge-of-the-horns-cities-of-light-will-they-ever-actually-be-built/

- The Times, London, 1799, 1857, 1858, 1963

Coordinates: 12°40′N 43°25′E / 12.66°N 43.42°E