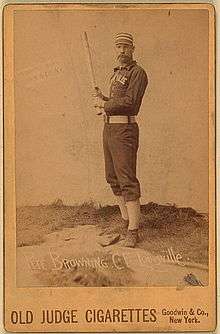

Pete Browning

| Pete Browning | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Outfielder | |||

|

Born: June 17, 1861 Louisville, Kentucky | |||

|

Died: September 10, 1905 (aged 44) Louisville, Kentucky | |||

| |||

| MLB debut | |||

| May 2, 1882, for the Louisville Eclipse | |||

| Last MLB appearance | |||

| September 30, 1894, for the Brooklyn Grooms | |||

| MLB statistics | |||

| Batting average | .341 | ||

| Home runs | 46 | ||

| Runs batted in | 659 | ||

| Teams | |||

| |||

| Career highlights and awards | |||

| |||

Louis Rogers "Pete" Browning (June 17, 1861 – September 10, 1905) was an American center and left fielder in Major League Baseball from 1882 to 1894 who played primarily for the Louisville Eclipse/Colonels, becoming one of the sport's most accomplished batters of the 1880s.

A three-time batting champion, he finished among the top three hitters in the league in each of his first seven years; only twice in his eleven full seasons did he finish lower than sixth. During the era before 1893, when the pitching distance was lengthened from 50 feet to 60 feet 6 inches, Browning ranked third among all major league players in career batting average, and fifth in slugging average. His .341 lifetime batting average remains one of the highest in major league history, and among the top five by a right-handed batter; his .345 average over eight American Association seasons was the highest mark by any player during that league's 10-year existence.

Nicknamed the "Louisville Slugger", he was enormously attentive to the bats he used, and was the first player to have them custom-made, establishing a practice among hitters which continues to the present. Playing in spite of serious medical afflictions which rendered him virtually deaf and subjected him to massive headaches, he resorted to alcohol to subdue the pain, but continued to hit well even as his drinking increased. He was also known as "The Gladiator", though sources differ as to whether the nickname applied to his struggles with ownership, the press, his drinking problem, or particularly elusive fly balls.

Early years

Born in Louisville, Kentucky, Browning was the youngest of eight children. His father, a grocer, was killed by a cyclone when Browning was thirteen years old. Young Pete remained with his mother, ultimately living in the house where he had grown up until the day he died.

He displayed considerable athletic prowess from an early age, and in 1877 began playing for a local semipro team, the Louisville Eclipse, and pitched an exhibition win against a National League team. He continued with the Eclipse into 1882, when the franchise became a member of the newly formed American Association, the first major league to rival the NL.

Professional career

Early career in Louisville

Browning quickly distinguished himself as an exceptional slugger. He led the league in both batting (.378) and slugging (.510) in its first season, also finishing in the top five in home runs, runs, hits and total bases. He was consistently among the league's top batters through 1888, winning a second batting crown in 1885 and hitting .402 in 1887. In 1884, he acquired his first custom-made bat from the Hillerich & Bradsby company, collecting three hits in his first game using it and beginning a baseball tradition.

Twice in the decade, he hit for the cycle: on August 8, 1886, and again on June 7, 1889. He also led the league in hits, total bases and on-base percentage in 1885. After suffering from mastoiditis from a young age, which caused him to lose his hearing and embarrassed him into avoiding school, resulting in essential illiteracy, he underwent the first of several surgeries to alleviate the condition in 1884, though the problem would afflict him throughout his career.

Other aspects of Browning's game were less polished; he has usually been regarded as one of the worst fielders in major league history, although some recent assessments have begun to question that view. American Gladiator, his first biography, recounted numerous "web gems" by Browning from the beginning of his career to the very end. The revised assessment is that Browning was a superb outfielder when he was sober and not suffering from the effects of mastoiditis, a serious infection of the inner ear usually contracted during childhood.

After being used primarily as an infielder in his first three seasons, playing every position except catcher over that span, he was shifted to the outfield on a permanent basis in 1885. While the inferior equipment of the time is somewhat of a mitigating factor, Browning's playing record presented various evidence against any hidden defensive prowess. So did his unusual habit of playing the infield while standing on one leg, which he claimed to have adopted in order to avoid collisions with other players; however, some sources have noted that his probable rationale was to gain an advantage against baserunners he could not hear by aiming one leg toward them, and that he continued to do so in the outfield because he couldn't hear his teammates on either side. An oft-reported story, possibly apocryphal, features one of Browning's managers claiming that the team would be better off with a wooden statue of an Indian in the outfield, since there was at least a slim chance that a batted ball might strike the statue and rebound back in the direction of the field. Indeed, he led league outfielders in errors in both 1886 and 1887. Browning's baserunning was also considered sub-par, exacerbated by his refusal to slide.

Later career

Browning lost his appetite for playing in Louisville during a hellish 1889 season. That year, the luckless franchise (by now known as the Colonels) finished last in the league with 27 wins and 111 losses, 66.5 games behind the top club. The season included not only a major league record 26-game losing streak, but also a narrow escape from the Johnstown Flood and the sport's first-ever strike. In the dispute, Browning was one of six players who refused to take the field as a protest against a series of heavy fines assessed by team owner Mordecai Davidson. The game took place as scheduled with the assistance of three local amateurs, and the striking players returned to work before the next contest. Browning finished the season with a .256 average, the first time he was not among the league's top three hitters. He left the American Association after eight seasons with a .345 career average, which would stand as the best mark by any player with more than one season in the league; Tip O'Neill ranks second at .343.

As a result of these events, as well as other labor disputes throughout the sport, Browning — along with nearly all the game's stars — chose to jump to the Players' League for the 1890 season, and played for the Cleveland Infants. The American Association had long been considered inferior to the NL, but in that season Browning proved that he was indeed among the game's top hitters by winning his third batting title with a .373 mark. The league dissolved after its sole season, and Browning spent the remaining four years of his career bouncing around between franchises in the NL. He spent time with the Pittsburgh Pirates (1891) and Cincinnati Reds (1891–92), then was back with the Colonels, who had joined the NL in a league merger (1892–93), before ending his major-league career in 1894 with a handful of appearances for the St. Louis Browns and Brooklyn Bridegrooms in the National League. (He began the 1894 season playing minor-league ball for "Kelly's Killers" of Allentown, Pa. in the Pennsylvania State League. The team was managed by future Hall-of-Famer Mike "King" Kelly.)

His last professional season was in 1896 with the Columbus Buckeyes in the Western League.

In the years before 1893, among players with at least 2500 career at bats, his batting average of .341 ranked behind only Dan Brouthers (.343) and Dave Orr (.342), with his slugging mark of .467 trailing only those of Brouthers (.520), Orr (.502), Roger Connor (.488) and Sam Thompson (.468). His recognized career hit total through 1893 ranked 10th in major league history to that point. Brouthers, a five-time champion, was the only other major league player to win more than two batting titles in the 19th century.

Personal life

Browning was tormented for his entire life by mastoiditis, which can result in deafness, vertigo, facial palsy, and brain damage. As a result, he lost his hearing at a young age, and was faced with frequent bouts of crippling head pain. The deafness had led Browning to drop out of school at an early age, so that he went through life as a virtual illiterate, and in order to deaden the physical pain resulting from his condition, he began drinking heavily in his youth. The drinking quickly spiraled out of control; he often appeared on the field while drunk, and was suspended for the final two months of the 1889 season for drunkenness, along with other shorter suspensions at different times. He was unable to stop, however, frequently stating, "I can't hit the ball until I hit the bottle."

Browning was a man of eccentric personal habits, particularly in relation to his bats. He spoke to them, and gave each one a name, often that of a Biblical figure. In the belief that any individual bat contained only a certain number of hits, he would periodically "retire" bats, keeping vast numbers of the retired ones in the home he shared with his mother. These bats were 37 inches long and 48 ounces in weight, enormous even by the standards of the time. He also habitually stared at the sun, thinking that by doing so, he would strengthen his eyes. He also "cleansed" his eyes when travelling by train by sticking his head out the window in an effort to catch cinders in them. Browning also computed his average on his cuffs on a regular basis, and was not above announcing to all when his train arrived at a depot that he was the champion batter of the American Association.

He remained a lifelong bachelor, though his affection for prostitutes was a matter of much discussion in the newspapers. He was the uncle of film director Tod Browning.[1]

After his retirement as a player, Browning worked as a cigar salesman and owned a bar, which ultimately failed; but his physical condition continued to deteriorate due to the mastoiditis and resulting complications. He remained a popular Louisville figure until June 7, 1905, when he was declared insane and committed to a local asylum (Lakeland). A sister released him two weeks later, but a month after that, he was in the hospital, suffering from a general physical collapse.

He died in Louisville on September 10 of that year at age 44. The specific cause of death was listed as asthenia (a weakening of the body), a cover-all medical term used by doctors of that time. However, he no doubt suffered from a wide variety of serious physical complaints. In addition to the mastoiditis, he was afflicted with cancer, advanced cirrhosis of the liver, alcohol-related brain damage, and according to some sources, paresis. Some sources erroneously report that he died in an insane asylum; he was in Lakeland Asylum a short time before he died. He is buried in historic Cave Hill Cemetery in Louisville.

Historical impact

Browning was an important figure in baseball's history. In addition to his accomplishments as a player, which have made him a popular candidate for the Baseball Hall of Fame, his legacy is expressed in the game in other ways as well. Browning is probably best remembered today as the inspiration behind the Hillerich & Bradsby company's popular "Louisville Slugger" line of baseball bats. He was the first player to purchase a bat from the company, and they adopted the name a few years later to honor his patronage and capitalize on his fame.

Browning's decision to sign with Pittsburgh in 1891 is noteworthy, as this transaction helped cement the team's new nickname of "Pirates". When the Players' League collapsed, its members were supposed to return to their franchises from the prior season. Pittsburgh, though, signed several players who were theoretically under the control of other clubs, starting with second baseman Lou Bierbauer. Other franchises decried these acts of "piracy", and the name stuck.

The strike by Browning and his Louisville teammates is also important in that it was the first labor action in what was ultimately a long series of disputes between players and management, prefacing the formation and collapse of the Players' League.

In 1984, a new grave marker was dedicated for Pete Browning, one that correctly spelled his name and listed all his major baseball achievements. The new marker was the idea of Philip Von Borries, who wrote the copy for the new marker and who also co-designed the marker. The ceremonies, jointly held by the city of Louisville and the Hillerich & Bradsby Company, came during the company's centennial celebration of their famed Louisville Slugger bat (of which Browning is the namesake).

There is a Browning's Restaurant & Brewery adjacent to Louisville Slugger Field.

The Nineteenth Century Committee of the Society for American Baseball Research named Browning the Overlooked 19th Century Baseball Legend for 2009 — a 19th-century player, manager, executive or other baseball personality not yet inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York.

See also

- List of Major League Baseball career stolen bases leaders

- List of Major League Baseball batting champions

- List of Major League Baseball annual doubles leaders

- Hitting for the cycle

External links

- Career statistics and player information from Baseball-Reference, or Baseball-Reference (Minors)

- Browning's entry in the Society for American Baseball Research's baseball biography project

- Grave of Pete Browning, with GPS coordinates Cave Hill Cemetery

References

- ↑ Kleber, John. "Louis Rodgers 'Pete' Browning", in The encyclopedia of Louisville, University Press of Kentucky, 2001, p. 137. ISBN 0-8131-2100-0

- Baseball: The Biographical Encyclopedia (2000). Kingston, New York: Total/Sports Illustrated. ISBN 1-892129-34-5.

- American Gladiator: The Life and Times Of Pete Browning (2007). Philip Von Borries. Bangor, Maine: Booklocker.com. ISBN 978-1-60145-272-6.

- AMERIDI (American Diamonds): An American Baseball Reader (2008). Philip Von Borries. Bangor, Maine: Booklocker.com. ISBN 978-1-60145-411-9.

- JockBio.com: Two-part biography of Pete Browning. Philip Von Borries. 2004.

- Biography of Pete Browning. Philip Von Borries. SABR biography project.