Pharmacy

| |

| Occupation | |

|---|---|

| Names | Pharmacist, Chemist, Doctor of Pharmacy, Druggist, Apothecary or simply Doctor |

Occupation type | Professional |

Activity sectors | health care, health sciences, chemical sciences |

| Description | |

| Competencies | The ethics, art and science of medicine, analytical skills, critical thinking |

Education required | Doctor of Pharmacy, Master of Pharmacy, Bachelor of Pharmacy |

Related jobs | Doctor, pharmacy technician, toxicologist, chemist, pharmacy assistant, other medical specialists |

Pharmacy is the science and technique of preparing and dispensing drugs. It is a health profession that links health sciences with chemical sciences and aims to ensure the safe and effective use of pharmaceutical drugs.

The scope of pharmacy practice includes more traditional roles such as compounding and dispensing medications, and it also includes more modern services related to health care, including clinical services, reviewing medications for safety and efficacy, and providing drug information. Pharmacists, therefore, are the experts on drug therapy and are the primary health professionals who optimize use of medication for the benefit of the patients.

An establishment in which pharmacy (in the first sense) is practiced is called a pharmacy (this term is more common in the United States) or a chemist's (which is more common in Great Britain). In the United States and Canada, drugstores commonly sell medicines, as well as miscellaneous items such as confectionery, cosmetics, office supplies, toys, hair care products and magazines and occasionally refreshments and groceries.

The word pharmacy is derived from its root word pharma, which had first been used sometime in the 15th–17th centuries. However, the original Greek roots from pharmakos imply sorcery or even poison. In addition to pharma responsibilities, the pharma offered general medical advice and a range of services that are now performed solely by other specialist practitioners, such as surgery and midwifery. The pharma (as it was referred to) often operated through a retail shop which, in addition to ingredients for medicines, sold tobacco and patent medicines. Often the place that did this was called an apothecary and several languages have this as the dominant term, though their practices are more akin to a modern pharmacy, in English the term apothecary would today be seen as outdated or only approproriate if herbal remedies were on offer to a large extent. The pharmas also used many other herbs not listed. The Greek word Pharmakeia (Greek: φαρμακεία) derives from pharmakon (φάρμακον), meaning "drug", "medicine" (or "poison").[1][n 1]

In its investigation of herbal and chemical ingredients, the work of the pharma may be regarded as a precursor of the modern sciences of chemistry and pharmacology, prior to the formulation of the scientific method.

Disciplines

The field of pharmacy can generally be divided into three primary disciplines:

The boundaries between these disciplines and with other sciences, such as biochemistry, are not always clear-cut. Often, collaborative teams from various disciplines (pharmacists and other scientists) work together toward the introduction of new therapeutics and methods for patient care. However, pharmacy is not a basic or biomedical science in its typical form. Medicinal chemistry is also a distinct branch of synthetic chemistry combining pharmacology, organic chemistry, and chemical biology.

Pharmacology is sometimes considered as the 4th discipline of pharmacy. Although pharmacology is essential to the study of pharmacy, it is not specific to pharmacy. Both disciplines are distinct.Those who wish to practice both pharmacy (patient oriented) and pharmacology (a biomedical science requiring the scientific method) receive separate training and degrees unique to either discipline.

Pharmacoinformatics is considered another new discipline, for systematic drug discovery and development with efficiency and safety.

Professionals

The World Health Organization estimates that there are at least 2.6 million pharmacists and other pharmaceutical personnel worldwide.[3]

Pharmacists

Pharmacists are healthcare professionals with specialised education and training who perform various roles to ensure optimal health outcomes for their patients through the quality use of medicines. Pharmacists may also be small-business proprietors, owning the pharmacy in which they practice. Since pharmacists know about the mode of action of a particular drug, and its metabolism and physiological effects on the human body in great detail, they play an important role in optimisation of a drug treatment for an individual.

Pharmacists are represented internationally by the International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP). They are represented at the national level by professional organisations such as the Royal Pharmaceutical Society in the UK, the Pharmaceutical Society of Australia (PSA), the Canadian Pharmacists Association (CPhA),the Pakistan Pharmacists Association (PPA), and the American Pharmacists Association (APhA), See also: List of pharmacy associations.

In some cases, the representative body is also the registering body, which is responsible for the regulation and ethics of the profession.

In the United States, specializations in pharmacy practice recognized by the Board of Pharmacy Specialties include: cardiovascular, infectious disease, oncology, pharmacotherapy, nuclear, nutrition, and psychiatry.[4] The Commission for Certification in Geriatric Pharmacy certifies pharmacists in geriatric pharmacy practice. The American Board of Applied Toxicology certifies pharmacists and other medical professionals in applied toxicology.

Pharmacy technicians

Pharmacy technicians support the work of pharmacists and other health professionals by performing a variety of pharmacy related functions, including dispensing prescription drugs and other medical devices to patients and instructing on their use. They may also perform administrative duties in pharmaceutical practice, such as reviewing prescription requests with medics's offices and insurance companies to ensure correct medications are provided and payment is received.

A Pharmacy Technician in the UK is considered a health care professional and often does not work under the direct supervision of a pharmacist (if employed in a hospital pharmacy) but instead is supervised and managed by other senior pharmacy technicians. In the UK the role of a PhT has grown and responsibility has been passed on to them to manage the pharmacy department and specialised areas in pharmacy practice allowing pharmacists the time to specialise in their expert field as medication consultants spending more time working with patients and in research. A pharmacy technician once qualified has to register as a professional on the General Pharmaceutical Council (GPhC) register. The GPhC is the governing body for pharmacy health care professionals and this is who regulates the practice of pharmacists and pharmacy technicians.

In the US, pharmacy technicians perform their duties under supervision of pharmacists. Although they may perform, under supervision, most dispensing, compounding and other tasks, they are not generally allowed to perform the role of counseling patients on the proper use of their medications.

History

The earliest known compilation of medicinal substances was the Sushruta Samhita, an Indian Ayurvedic treatise attributed to Sushruta in the 6th century BC. However, the earliest text as preserved dates to the 3rd or 4th century AD.

Many Sumerian (late 6th millennium BC – early 2nd millennium BC) cuneiform clay tablets record prescriptions for medicine.[5]

Ancient Egyptian pharmacological knowledge was recorded in various papyri such as the Ebers Papyrus of 1550 BC, and the Edwin Smith Papyrus of the 16th century BC.

In Ancient Greece, Diocles of Carystus (4th century BC) was one of several men studying the medicinal properties of plants. He wrote several treatises on the topic.[6] The Greek physician Pedanius Dioscorides is famous for writing a five volume book in his native Greek Περί ύλης ιατρικής in the 1st century AD. The Latin translation De Materia Medica (Concerning medical substances) was used a basis for many medieval texts, and was built upon by many middle eastern scientists during the Islamic Golden Age. The title coined the term materia medica.

The earliest known Chinese manual on materia medica is the Shennong Bencao Jing (The Divine Farmer's Herb-Root Classic), dating back to the 1st century AD. It was compiled during the Han dynasty and was attributed to the mythical Shennong. Earlier literature included lists of prescriptions for specific ailments, exemplified by a manuscript "Recipes for 52 Ailments", found in the Mawangdui, sealed in 168 BC. Further details on Chinese pharmacy can be found in the Pharmacy in China article.

In Japan, at the end of the Asuka period (538–710) and the early Nara period (710–794), the men who fulfilled roles similar to those of modern pharmacists were highly respected. The place of pharmacists in society was expressly defined in the Taihō Code (701) and re-stated in the Yōrō Code (718). Ranked positions in the pre-Heian Imperial court were established; and this organizational structure remained largely intact until the Meiji Restoration (1868). In this highly stable hierarchy, the pharmacists—and even pharmacist assistants—were assigned status superior to all others in health-related fields such as physicians and acupuncturists. In the Imperial household, the pharmacist was even ranked above the two personal physicians of the Emperor.[7]

There is a stone sign for a pharmacy with a tripod, a mortar, and a pestle opposite one for a doctor in the Arcadian Way in Ephesus near Kusadasi in Turkey.[8] The current Ephesus dates back to 400 BC and was the site of the Temple of Artemis, one of the seven wonders of the world.

In Baghdad the first pharmacies, or drug stores, were established in 754,[9] under the Abbasid Caliphate during the Islamic Golden Age. By the 9th century, these pharmacies were state-regulated.[10]

The advances made in the Middle East in botany and chemistry led medicine in medieval Islam substantially to develop pharmacology. Muhammad ibn Zakarīya Rāzi (Rhazes) (865–915), for instance, acted to promote the medical uses of chemical compounds. Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi (Abulcasis) (936–1013) pioneered the preparation of medicines by sublimation and distillation. His Liber servitoris is of particular interest, as it provides the reader with recipes and explains how to prepare the `simples’ from which were compounded the complex drugs then generally used. Sabur Ibn Sahl (d 869), was, however, the first physician to initiate pharmacopoedia, describing a large variety of drugs and remedies for ailments. Al-Biruni (973–1050) wrote one of the most valuable Islamic works on pharmacology, entitled Kitab al-Saydalah (The Book of Drugs), in which he detailed the properties of drugs and outlined the role of pharmacy and the functions and duties of the pharmacist. Avicenna, too, described no less than 700 preparations, their properties, modes of action, and their indications. He devoted in fact a whole volume to simple drugs in The Canon of Medicine. Of great impact were also the works by al-Maridini of Baghdad and Cairo, and Ibn al-Wafid (1008–1074), both of which were printed in Latin more than fifty times, appearing as De Medicinis universalibus et particularibus by 'Mesue' the younger, and the Medicamentis simplicibus by 'Abenguefit'. Peter of Abano (1250–1316) translated and added a supplement to the work of al-Maridini under the title De Veneris. Al-Muwaffaq’s contributions in the field are also pioneering. Living in the 10th century, he wrote The foundations of the true properties of Remedies, amongst others describing arsenious oxide, and being acquainted with silicic acid. He made clear distinction between sodium carbonate and potassium carbonate, and drew attention to the poisonous nature of copper compounds, especially copper vitriol, and also lead compounds. He also describes the distillation of sea-water for drinking.[11]

In Europe pharmacy-like shops began to appear during the 12th century. In 1240 emperor Frederic II issued a decree by which the physician's and the apothecary's professions were separated.[12] The first pharmacy in Europe (still working) was opened in 1241 in Trier, Germany.

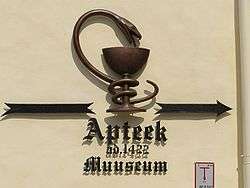

In Europe there are old pharmacies still operating in Dubrovnik, Croatia, located inside the Franciscan monastery, opened in 1317; and in the Town Hall Square of Tallinn, Estonia, dating from at least 1422. The oldest is claimed to have been set up in 1221 in the Church of Santa Maria Novella in Florence, Italy, which now houses a perfume museum. The medieval Esteve Pharmacy, located in Llívia, a Catalan enclave close to Puigcerdà, also now a museum, dates back to the 15th century, keeping albarellos from the 16th and 17th centuries, old prescription books and antique drugs.

Types of pharmacy practice areas

Pharmacists practice in a variety of areas including community pharmacies, hospitals, clinics, extended care facilities, psychiatric hospitals, and regulatory agencies. Pharmacists can specialize in various areas of practice including but not limited to: hematology/oncology, infectious diseases, ambulatory care, nutrition support, drug information, critical care, pediatrics, etc.

Community pharmacy

A pharmacy (commonly the chemist in Australia, New Zealand and the UK; or drugstore in North America; retail pharmacy in industry terminology; or Apothecary, historically) is the place where most pharmacists practice the profession of pharmacy. It is the community pharmacy where the dichotomy of the profession exists—health professionals who are also retailers.

Community pharmacies usually consist of a retail storefront with a dispensary where medications are stored and dispensed. According to Sharif Kaf al-Ghazal, the opening of the first drugstores are recorded by Muslim pharmacists in Baghdad in 754.[9][13]

In most countries, the dispensary is subject to pharmacy legislation; with requirements for storage conditions, compulsory texts, equipment, etc., specified in legislation. Where it was once the case that pharmacists stayed within the dispensary compounding/dispensing medications, there has been an increasing trend towards the use of trained pharmacy technicians while the pharmacist spends more time communicating with patients. Pharmacy technicians are now more dependent upon automation to assist them in their new role dealing with patients' prescriptions and patient safety issues.

Pharmacies are typically required to have a pharmacist on-duty at all times when open. It is also often a requirement that the owner of a pharmacy must be a registered pharmacist, although this is not the case in all jurisdictions, such that many retailers (including supermarkets and mass merchandisers) now include a pharmacy as a department of their store.

Likewise, many pharmacies are now rather grocery store-like in their design. In addition to medicines and prescriptions, many now sell a diverse arrangement of additional items such as cosmetics, shampoo, office supplies, confections, snack foods, durable medical equipment, greeting cards, and provide photo processing services.

Hospital pharmacy

Pharmacies within hospitals differ considerably from community pharmacies. Some pharmacists in hospital pharmacies may have more complex clinical medication management issues whereas pharmacists in community pharmacies often have more complex business and customer relations issues.

Because of the complexity of medications including specific indications, effectiveness of treatment regimens, safety of medications (i.e., drug interactions) and patient compliance issues (in the hospital and at home) many pharmacists practicing in hospitals gain more education and training after pharmacy school through a pharmacy practice residency and sometimes followed by another residency in a specific area. Those pharmacists are often referred to as clinical pharmacists and they often specialize in various disciplines of pharmacy. For example, there are pharmacists who specialize in hematology/oncology, HIV/AIDS, infectious disease, critical care, emergency medicine, toxicology, nuclear pharmacy, pain management, psychiatry, anti-coagulation clinics, herbal medicine, neurology/epilepsy management, pediatrics, neonatal pharmacists and more.

Hospital pharmacies can often be found within the premises of the hospital. Hospital pharmacies usually stock a larger range of medications, including more specialized medications, than would be feasible in the community setting. Most hospital medications are unit-dose, or a single dose of medicine. Hospital pharmacists and trained pharmacy technicians compound sterile products for patients including total parenteral nutrition (TPN), and other medications given intravenously. This is a complex process that requires adequate training of personnel, quality assurance of products, and adequate facilities. Several hospital pharmacies have decided to outsource high risk preparations and some other compounding functions to companies who specialize in compounding. The high cost of medications and drug-related technology, combined with the potential impact of medications and pharmacy services on patient-care outcomes and patient safety, make it imperative that hospital pharmacies perform at the highest level possible.

Clinical pharmacy

Pharmacists provide direct patient care services that optimizes the use of medication and promotes health, wellness, and disease prevention.[14] Clinical pharmacists care for patients in all health care settings, but the clinical pharmacy movement initially began inside hospitals and clinics. Clinical pharmacists often collaborate with physicians and other healthcare professionals to improve pharmaceutical care. Clinical pharmacists are now an integral part of the interdisciplinary approach to patient care. They often participate in patient care rounds for drug product selection.

The clinical pharmacist's role involves creating a comprehensive drug therapy plan for patient-specific problems, identifying goals of therapy, and reviewing all prescribed medications prior to dispensing and administration to the patient. The review process often involves an evaluation of the appropriateness of the drug therapy (e.g., drug choice, dose, route, frequency, and duration of therapy) and its efficacy. The pharmacist must also monitor for potential drug interactions, adverse drug reactions, and assess patient drug allergies while designing and initiating a drug therapy plan.[15]

Ambulatory care pharmacy

Since the emergence of modern clinical pharmacy, ambulatory care pharmacy practice has emerged as a unique pharmacy practice setting. Ambulatory care pharmacy is based primarily on pharmacotherapy services that a pharmacist provides in a clinic. Pharmacists in this setting often do not dispense drugs, but rather see patients in office visits to manage chronic disease states.

In the U.S. federal health care system (including the VA, the Indian Health Service, and NIH) ambulatory care pharmacists are given full independent prescribing authority. In some states such North Carolina and New Mexico these pharmacist clinicians are given collaborative prescriptive and diagnostic authority.[16] In 2011 the board of Pharmaceutical Specialties approved ambulatory care pharmacy practice as a separate board certification. The official designation for pharmacists who pass the ambulatory care pharmacy specialty certification exam will be Board Certified Ambulatory Care Pharmacist and these pharmacists will carry the initials BCACP.[17]

Compounding pharmacy

Compounding is the practice of preparing drugs in new forms. For example, if a drug manufacturer only provides a drug as a tablet, a compounding pharmacist might make a medicated lollipop that contains the drug. Patients who have difficulty swallowing the tablet may prefer to suck the medicated lollipop instead.

Another form of compounding is by mixing different strengths (g,mg,mcg) of capsules or tablets to yield the desired amount of medication indicated by the physician, physician assistant, Nurse Practitioner, or clinical pharmacist practitioner. This form of compounding is found at community or hospital pharmacies or in-home administration therapy.

Compounding pharmacies specialize in compounding, although many also dispense the same non-compounded drugs that patients can obtain from community pharmacies.

Consultant pharmacy

Consultant pharmacy practice focuses more on medication regimen review (i.e. "cognitive services") than on actual dispensing of drugs. Consultant pharmacists most typically work in nursing homes, but are increasingly branching into other institutions and non-institutional settings.[18] Traditionally consultant pharmacists were usually independent business owners, though in the United States many now work for several large pharmacy management companies (primarily Omnicare, Kindred Healthcare and PharMerica). This trend may be gradually reversing as consultant pharmacists begin to work directly with patients, primarily because many elderly people are now taking numerous medications but continue to live outside of institutional settings. Some community pharmacies employ consultant pharmacists and/or provide consulting services.

The main principle of consultant pharmacy is developed by Hepler and Strand in 1990.[19][20]

Internet pharmacy

Since about the year 2000, a growing number of Internet pharmacies have been established worldwide. Many of these pharmacies are similar to community pharmacies, and in fact, many of them are actually operated by brick-and-mortar community pharmacies that serve consumers online and those that walk in their door. The primary difference is the method by which the medications are requested and received. Some customers consider this to be more convenient and private method rather than traveling to a community drugstore where another customer might overhear about the drugs that they take. Internet pharmacies (also known as online pharmacies) are also recommended to some patients by their physicians if they are homebound.

While most Internet pharmacies sell prescription drugs and require a valid prescription, some Internet pharmacies sell prescription drugs without requiring a prescription. Many customers order drugs from such pharmacies to avoid the "inconvenience" of visiting a doctor or to obtain medications which their doctors were unwilling to prescribe. However, this practice has been criticized as potentially dangerous, especially by those who feel that only doctors can reliably assess contraindications, risk/benefit ratios, and an individual's overall suitability for use of a medication. There also have been reports of such pharmacies dispensing substandard products.[21]

Of particular concern with Internet pharmacies is the ease with which people, youth in particular, can obtain controlled substances (e.g., Vicodin, generically known as hydrocodone) via the Internet without a prescription issued by a doctor/practitioner who has an established doctor-patient relationship. There are many instances where a practitioner issues a prescription, brokered by an Internet server, for a controlled substance to a "patient" s/he has never met. In the United States, in order for a prescription for a controlled substance to be valid, it must be issued for a legitimate medical purpose by a licensed practitioner acting in the course of legitimate doctor-patient relationship. The filling pharmacy has a corresponding responsibility to ensure that the prescription is valid. Often, individual state laws outline what defines a valid patient-doctor relationship.

Canada is home to dozens of licensed Internet pharmacies, many of which sell their lower-cost prescription drugs to U.S. consumers, who pay one of the world's highest drug prices.[22] In recent years, many consumers in the US and in other countries with high drug costs, have turned to licensed Internet pharmacies in India, Israel and the UK, which often have even lower prices than in Canada.

In the United States, there has been a push to legalize importation of medications from Canada and other countries, in order to reduce consumer costs. While in most cases importation of prescription medications violates Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulations and federal laws, enforcement is generally targeted at international drug suppliers, rather than consumers. There is no known case of any U.S. citizens buying Canadian drugs for personal use with a prescription, who has ever been charged by authorities.

Veterinary pharmacy

Veterinary pharmacies, sometimes called animal pharmacies, may fall in the category of hospital pharmacy, retail pharmacy or mail-order pharmacy. Veterinary pharmacies stock different varieties and different strengths of medications to fulfill the pharmaceutical needs of animals. Because the needs of animals, as well as the regulations on veterinary medicine, are often very different from those related to people, veterinary pharmacy is often kept separate from regular pharmacies.

Nuclear pharmacy

Nuclear pharmacy focuses on preparing radioactive materials for diagnostic tests and for treating certain diseases. Nuclear pharmacists undergo additional training specific to handling radioactive materials, and unlike in community and hospital pharmacies, nuclear pharmacists typically do not interact directly with patients.

Military pharmacy

Military pharmacy is an entirely different working environment due to the fact that technicians perform most duties that in a civilian sector would be illegal. State laws of Technician patient counseling and medication checking by a pharmacist do not apply.

Pharmacy informatics

Pharmacy informatics is the combination of pharmacy practice science and applied information science. Pharmacy informaticists work in many practice areas of pharmacy, however, they may also work in information technology departments or for healthcare information technology vendor companies. As a practice area and specialist domain, pharmacy informatics is growing quickly to meet the needs of major national and international patient information projects and health system interoperability goals. Pharmacists in this area are trained to participate in medication management system development, deployment and optimization.

Specialty pharmacy

Specialty pharmacies supply high cost injectable, oral, infused, or inhaled medications that are used for chronic and complex disease states such as cancer, hepatitis, and rheumatoid arthritis.[23] Unlike a traditional community pharmacy where prescriptions for any common medication can be brought in and filled, specialty pharmacies carry novel medications that need to be properly stored, administered, carefully monitored, and clinically managed.[24] In addition to supplying these drugs, specialty pharmacies also provide lab monitoring, adherence counseling, and assist patients with cost-containment strategies needed to obtain their expensive specialty drugs.[25] It is currently the fastest growing sector of the pharmaceutical industry with 19 of 28 newly FDA approved medications in 2013 being specialty drugs.[26]

Due to the demand for clinicians who can properly manage these specific patient populations, the Specialty Pharmacy Certification Board has developed a new certification exam to certify specialty pharmacists. Along with the 100 question computerized multiple-choice exam, pharmacists must also complete 3,000 hours of specialty pharmacy practice within the past three years as well as 30 hours of specialty pharmacist continuing education within the past two years.[27]

Issues in pharmacy

Separation of prescribing from dispensing

In most jurisdictions (such as the United States), pharmacists are regulated separately from physicians. These jurisdictions also usually specify that only pharmacists may supply scheduled pharmaceuticals to the public, and that pharmacists cannot form business partnerships with physicians or give them "kickback" payments. However, the American Medical Association (AMA) Code of Ethics provides that physicians may dispense drugs within their office practices as long as there is no patient exploitation and patients have the right to a written prescription that can be filled elsewhere. 7 to 10 percent of American physicians practices reportedly dispense drugs on their own.[28]

In some rural areas in the United Kingdom, there are dispensing physicians[29] who are allowed to both prescribe and dispense prescription-only medicines to their patients from within their practices. The law requires that the GP practice be located in a designated rural area and that there is also a specified, minimum distance (currently 1.6 kilometres) between a patient's home and the nearest retail pharmacy. This law also exists in Austria for general physicians if the nearest pharmacy is more than 4 kilometers away, or where none is registered in the city.

In other jurisdictions (particularly in Asian countries such as China, Malaysia, and Singapore), doctors are allowed to dispense drugs themselves and the practice of pharmacy is sometimes integrated with that of the physician, particularly in traditional Chinese medicine.

In Canada it is common for a medical clinic and a pharmacy to be located together and for the ownership in both enterprises to be common, but licensed separately.

The reason for the majority rule is the high risk of a conflict of interest and/or the avoidance of absolute powers. Otherwise, the physician has a financial self-interest in "diagnosing" as many conditions as possible, and in exaggerating their seriousness, because he or she can then sell more medications to the patient. Such self-interest directly conflicts with the patient's interest in obtaining cost-effective medication and avoiding the unnecessary use of medication that may have side-effects. This system reflects much similarity to the checks and balances system of the U.S. and many other governments.

A campaign for separation has begun in many countries and has already been successful (as in Korea). As many of the remaining nations move towards separation, resistance and lobbying from dispensing doctors who have pecuniary interests may prove a major stumbling block (e.g. in Malaysia).

The future of pharmacy

In the coming decades, pharmacists are expected to become more integral within the health care system. Rather than simply dispensing medication, pharmacists are increasingly expected to be compensated for their patient care skills.[30] In particular, Medication Therapy Management (MTM) includes the clinical services that pharmacists can provide for their patients. Such services include the thorough analysis of all medication (prescription, non-prescription, and herbals) currently being taken by an individual. The result is a reconciliation of medication and patient education resulting in increased patient health outcomes and decreased costs to the health care system.[31]

This shift has already commenced in some countries; for instance, pharmacists in Australia receive remuneration from the Australian Government for conducting comprehensive Home Medicines Reviews. In Canada, pharmacists in certain provinces have limited prescribing rights (as in Alberta and British Columbia) or are remunerated by their provincial government for expanded services such as medications reviews (Medschecks in Ontario). In the United Kingdom, pharmacists who undertake additional training are obtaining prescribing rights and this is because of pharmacy education. They are also being paid for by the government for medicine use reviews. In Scotland the pharmacist can write prescriptions for Scottish registered patients of their regular medications, for the majority of drugs, except for controlled drugs, when the patient is unable to see their doctor, as could happen if they are away from home or the doctor is unavailable. In the United States, pharmaceutical care or clinical pharmacy has had an evolving influence on the practice of pharmacy.[32] Moreover, the Doctor of Pharmacy (Pharm. D.) degree is now required before entering practice and some pharmacists now complete one or two years of residency or fellowship training following graduation. In addition, consultant pharmacists, who traditionally operated primarily in nursing homes are now expanding into direct consultation with patients, under the banner of "senior care pharmacy."[33]

In addition to patient care, pharmacies will be a focal point for medical adherence initiatives. There is enough evidence to show that integrated pharmacy based initiatives significantly impact adherence for chronic patients. For example, a study published in NIH shows "pharmacy based interventions improved patients' medication adherence rates by 2.1 percent and increased physicians' initiation rates by 38 percent, compared to the control group".[34]

Pharmacy journals

See also

- American Society for Pharmacy Law

- Apothecary

- Bachelor of Pharmacy, Master of Pharmacy, Doctor of Pharmacy

- Classification of Pharmaco-Therapeutic Referrals

- Clinical pharmacy

- Consultant pharmacist

- Evidence-based pharmacy in developing countries

- History of pharmacy

- Hospital pharmacy

- International Pharmaceutical Federation

- International Pharmaceutical Students’ Federation

- List of pharmacies

- List of pharmacy associations

- List of pharmacy organizations in the United Kingdom

- List of pharmacy schools in the United States

- List of pharmacy schools

- Nuclear pharmacy

- Online pharmacy

- Pharmaceutical company

- Pharmaceutics

- Pharmaceutical industry

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacogenomics

- Pharmacognosy

- Pharmacology

- Pharmaconomist

- Pharmacy Automation - The Tablet Counter

- Pharmacy residency

- Pharmacy informatics

- Professional Further Education in Clinical Pharmacy and Public Health

- Raeapteek (one of the oldest continuously run pharmacies in Europe)

- Telepharmacy

Symbols

The two symbols most commonly associated with pharmacy in English-speaking countries are the mortar and pestle and the ℞ (recipere) character, which is often written as "Rx" in typed text. The show globe was also used until the early 20th century. Pharmacy organizations often use other symbols, such as the Bowl of Hygieia which is often used in the Netherlands, conical measures, and caduceuses in their logos. Other symbols are common in different countries: the green Greek cross in France, Argentina, the United Kingdom, Belgium, Ireland, Italy, Spain, and India, the increasingly rare Gaper in the Netherlands, and a red stylized letter A in Germany and Austria (from Apotheke, the German word for pharmacy, from the same Greek root as the English word 'apothecary').

Rod of Asclepius, the internationally recognised symbol of medicine

Rod of Asclepius, the internationally recognised symbol of medicine Green cross and Bowl of Hygieia used in Europe (with the exception of Germany and Austria) and India

Green cross and Bowl of Hygieia used in Europe (with the exception of Germany and Austria) and India Simple green cross, also used in Europe and India

Simple green cross, also used in Europe and India Red "A" (Apotheke) sign, used in Germany

Red "A" (Apotheke) sign, used in Germany Similar red "A" sign, used in Austria

Similar red "A" sign, used in Austria The mortar and pestle, used in the United States and Canada

The mortar and pestle, used in the United States and Canada A hanging Show globe, formerly used in the United States

A hanging Show globe, formerly used in the United States The Gaper, formerly used in the Netherlands

The Gaper, formerly used in the Netherlands The symbol used on medical prescriptions, from the Latin Recipe

The symbol used on medical prescriptions, from the Latin Recipe

Notes and references

- Notes

- References

- ↑ φάρμακον. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ↑ "PY 1314 Vn + frr. (Cii)". DĀMOS: Database of Mycenaean at Oslo. University of Oslo.Raymoure, K.A. "pe-re". Minoan Linear A & Mycenaean Linear B. Deaditerranean."The Linear B word pa-ma-ko". Palaeolexicon. Word study tool of ancient languages.

- ↑ World Health Organization. World Health Statistics 2011 - Table 6: Health workforce, infrastructure and essential medicines. Geneva, 2011. Accessed 21 July 2011.

- ↑ Board of Pharmacy Specialties, Current Specialties

- ↑ John K. Borchardt (2002). "The Beginnings of Drug Therapy: Ancient Mesopotamian Medicine". Drug News & Perspectives. 15 (3): 187–192. doi:10.1358/dnp.2002.15.3.840015. ISSN 0214-0934. PMID 12677263.

- ↑ Edward Kremers, Glenn Sonnedecker (1986). "Kremers and Urdang's History of pharmacy". Amer. Inst. History of Pharmacy. p.17. ISBN 0931292174

- ↑ Titsingh, Isaac. (1834) Annales des empereurs du japon, p. 434.

- ↑ has photos

- 1 2 Hadzovic, S (1997). "Pharmacy and the great contribution of Arab-Islamic science to its development". Medicinski Arhiv (in Croatian). 51 (1-2): 47–50. ISSN 0025-8083. OCLC 32564530. PMID 9324574.

- ↑ al-Ghazal, Sharif Kaf (October 2003). "The valuable contributions of Al-Razi (Rhazes) in the history of pharmacy during the Middle Ages" (PDF). Journal of the International Society for the History of Islamic Medicine. 2 (4): 9–11. ISSN 1303-667X. OCLC 54045642.

- ↑ Levey M. (1973), ‘ Early Arabic Pharmacology’, E. J. Brill; Leiden.

- ↑ History of Pharmacy Web Pages - Sweden´s oldest pharmacies

- ↑ Sharif Kaf al-Ghazal, Journal of the International Society for the History of Islamic Medicine, 2004 (3), pp. 3-9 [8].

- ↑ American College of Clinical Pharmacy. The definition of clinical pharmacy. Pharmacotherapy 2008;28(6):816-817.

- ↑ Burke JM, Miller WA, Spencer AP, et al. (2008). "Clinical pharmacist competencies" (PDF). Pharmacotherapy. 28 (6): 806–815. doi:10.1592/phco.28.6.806.

- ↑ Knapp, KK; Okamoto, MP; Black, BL (2005). "ASHP survey of ambulatory care pharmacy practice in health systems--2004". American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 62 (3): 274–84. PMID 15719585.

- ↑ BPS Approves Ambulatory Care Designation; Explores New Specialties in Pain and Palliative Care, Critical Care and Pediatrics

- ↑ American Society of Consultant Pharmacists, Frequently Asked Questions

- ↑ Strand LM (1990). "Pharmaceutical care and patient outcomes: notes on what it is we manage". Top Hosp Pharm Manage. 10 (2): 77–84. PMID 10128568.

- ↑ Hepler CD, Strand LM (1990). "Opportunities and responsibilities in pharmaceutical care". Am J Hosp Pharm. 47 (3): 533–43. PMID 2316538.

- ↑ Protecting Patients from Counterfeit and Other Substandard Drugs/Supply Chain Threats

- ↑ London Free Press Regional News Archive, Canada Internet Pharmacy Merged In $3.8 Million Deal

- ↑ NBCH Action Brief: Specialty Pharmacy. Specialty Pharmacy December, 2013. Accessed 27 October 2014.

- ↑ Wild, D. Specialty Pharmacy Continuum Carving a Specialty Niche Within the ACO Model." Volume 1 (Summer Issue). August, 2012.

- ↑ Shane, RR (15 August 2012). "Translating health care imperatives and evidence into practice: the "Institute of Pharmacy" report.". American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 69 (16): 1373–83. doi:10.2146/ajhp120292. PMID 22855102.

- ↑ "Health Care Cost Drivers: Spotlight on Specialty Drugs" (PDF). September 2014. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- ↑ Specialty Pharmacy Certification Board

- ↑ American Association of State Compensation Insurance Funds, Prepackaged Drugs in Workers' Compensation

- ↑ British Medical Association, briefing on dispensing doctors, 30 January 2009

- ↑ American College of Clinical Pharmacy, Evidence of the Economic Benefit of Clinical Pharmacy Services: 1996–2000

- ↑ American Pharmacy Student Alliance (APSA)

- ↑ American College of Clinical Pharmacy, Clinical Pharmacy Defined

- ↑ American Society of Consultant Pharmacists, What is a Senior Care Pharmacist?

- ↑ Brennan, Troyen A.; Dollear, Timothy J.; Hu, Min; Matlin, Olga S.; Shrank, William H.; Choudhry, Niteesh K.; Grambley, William (2012-01-01). "An integrated pharmacy-based program improved medication prescription and adherence rates in diabetes patients". Health Affairs (Project Hope). 31 (1): 120–129. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0931. ISSN 1544-5208. PMID 22232102.

References

- Watkins Elizabeth Siegel (2009). "From History of Pharmacy to Pharmaceutical History". Pharmacy in History. 51 (1): 3–13.

- (Japanese) Asai,T. (1985). Nyokan Tūkai. Tokyo: Kōdan-Sha.

- (French) Titsingh, Isaac, ed. (1834). [Siyun-sai Rin-siyo/Hayashi Gahō, 1652], Nipon o daï itsi ran; ou, Annales des empereurs du Japon. Paris: Oriental Translation Fund of Great Britain and Ireland....Click link for digitized, full-text copy of this book (in French)

- High Performance Pharmacy - A landmark study in hospital pharmacy performance based on an extensive literature review and the collective experience of the Health Systems Pharmacy Executive Alliance.

External links

| Look up pharmacy in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Pharmacy |

| Wikiversity has learning materials about Pharmacy |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pharmacy. |

- Navigator History of Pharmacy Collection of internet resources related to the history of pharmacy

- Soderlund Pharmacy Museum - Information about the history of the American Drugstore

- The Lloyd Library Library of botanical, medical, pharmaceutical, and scientific books and periodicals, and works of allied sciences

- American Institute of the History of Pharmacy American Institute of the History of Pharmacy—resources in the history of pharmacy

- International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP) Federation representing national associations of pharmacists and pharmaceutical scientists. Information and resources relating to pharmacy education, practice, science and policy

- Pharmaboard German association of pharmacy students