Philip Euen Mitchell

| Sir Philip Euen Mitchell G.C.M.G. | |

|---|---|

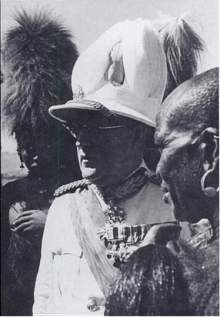

Sir Philip Euen Mitchell in Kenya, talking to tribal chiefs in 1952 | |

| 7th Governor of Uganda | |

|

In office 1935–1940 | |

| Monarch |

George V Edward VIII George VI |

| Preceded by | Bernard Henry Bourdillon |

| Succeeded by | Charles Dundas |

| 16th Governor of Fiji | |

|

In office 21 July 1942 – December 1944 | |

| Monarch | George VI |

| Preceded by | Harry Luke |

| Succeeded by | Alexander Grantham |

| 18th Governor of Kenya | |

|

In office 11 December 1944 – 21 June 1952 | |

| Monarch | George VI |

| Preceded by | Henry Monck-Mason Moore |

| Succeeded by | Sir Evelyn Baring |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

1 May 1890 London, United Kingdom |

| Died |

11 October 1964 (aged 74) Gibraltar |

| Citizenship | British |

| Spouse(s) | Margery Tyrwhitt-Drake |

| Alma mater | Trinity College, Oxford |

Sir Philip Euen Mitchell (1 May 1890 – 11 October 1964) was a British Colonial administrator who served as Governor of Uganda (1935–1940), Governor of Fiji (1942–1944) and Governor of Kenya (1944–1952).

Birth and education

Philip Euen Mitchell was born on 1 May 1890 in London to a Scottish family. His father, Captain Hugh Mitchell (1849–1937) had served in the Royal Engineers, and after retiring had studied law at the Inner Temple and had become a barrister.[1] His father had played for the Royal Engineers team in the 1872 FA Cup Final.[2] His mother, Mary Catherine née Creswell, died when he was two years old,[3] and his father moved to Gibraltar where he built up his legal practice, living at Campamento in Spain. Philip was educated by a French tutor, becoming equally fluent in English, French and Spanish. He won a scholarship to St Paul's School, London.[4]

From St Paul's, he won a classical scholarship at Trinity College, Oxford.[5] While at university he was a friend of Joyce Cary. His behaviour was often wild, risking encounters with the police or the university proctors. He was physically strong and good at most games, particularly golf.[6] He dropped out of University after two years and after losing his scholarship could not afford to return.[5]

Early career

Mitchell joined the Colonial Administrative Service in 1913.[7] He was sent to Zomba District in Nyasaland as an assistant resident. While there he learned the Nyanja language, with some difficulty since it is a Bantu language completely unrelated to European languages.[8] He served in the King's African Rifles during World War I (1914–1918).[7] During this period he became completely fluent in the Swahili language.[8] In 1922 he was promoted to District Commissioner at Tanga, a seaport on the coast of Tanganyika near the Kenyan border. In 1925, while on leave in South Africa, he married Margery Tyrwhitt-Drake.[9]

As Tanganyika Secretary for Native Affairs, in 1929 Mitchell supported cooperatives, and claimed that "in a sense every Bantu village is in fact a co-operative society". The Tanganyika government did not act on his recommendation, using lack of staff and budget as the reason.[10]

Colonial governor

Uganda

Mitchell was appointed Governor of Uganda in 1935. During the depression, capital expenditure in Uganda had been slashed, and public infrastructure and services had deteriorated. In 1936, Mitchell appointed a committee to set priorities for development and to provide for financing. He saw a need to completely review the relationship between Buganda and the government of the Protectorate. He was concerned with political reform, recognising that the eventual goal was self-government.[11] In 1937 he implemented reforms that increased the planning and budgetary capacity of the Secretariat, and introduced district-level planning teams working with the District Commissioners. All these changes had little time to show results when World War II (1939–1945) began.[12]

In mid-1940 Sir Philip was transferred to Nairobi to co-ordinate the East African war effort. In January 1941 he was appointed Chief Political Officer to General Sir Archibald Wavell, the Commander in Chief Middle East. He was given the delicate job of administering the Italian African colonies that had fallen to the British.[7] In January 1942, as Chief Political Officer for the Commander in Chief, East Africa, Major-General Sir Philip Euen Mitchell signed a treaty with the Emperor Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia. The reconquest of that country from the Italians had recently been completed.[13]

Fiji

Mitchell became Governor of Fiji, arriving there on 21 July 1942.[14] Mitchell was also British High Commissioner in the Western Pacific, and a large part of his job was to smooth out differences between the allied forces in the struggle with Japan.[15] Fiji had a mixed-race population of 210,518 of whom about 100,000 were Fijians and 90,000 Indians. Although the white and Fijian people were on good terms and often intermarried, there were tensions with the large Indian population, most of whom were descendants of indentured labourers.[14] Another issue was that, while the Fijian people were happy to belong to the British Empire, many of the Indians were in sympathy with the independence movement in India and could not be called loyal subjects. A further source of tension was that between Hindus and Muslims in the Indian community.[15]

Mitchell proposed that the islanders should be given greater power, but to his surprise found that the Fijians preferred the status quo, at least for the time being. Their reason was that they needed more time to develop experience in local government, or they would be dominated by the Indians. Mitchell nevertheless intended that Fiji should be put on course towards self-government, and wrote to the Colonial Office describing his views on how this would be achieved, and on the program for post-war reconstruction. Nothing was done about his recommendations during his term in office.[16]

Even while the Gilbert and Ellice Islands were under Japanese occupation, Mitchell was in charge of planning for the colony`s future after the British regained control. At first, he was in favour of merging the colony with Fiji, since he felt it was too small to be viable on its own. The Colonial Office would not accept this proposal. Later he moved to the idea that the Gilbert and Ellice Islands would have to remain as a Native Territory, but wanted the islanders to be trained so they could take on their own administration as far as possible.[17]

Kenya

Mitchell was Governor of Kenya from 11 December 1944 until 1952. In February 1952, he received Princess Elizabeth on a visit just before her father died and she ascended the throne as Queen Elizabeth II.[18]

Death

Mitchell died at the Royal Naval Hospital in Gibraltar on 11 October 1964 from heart failure, aged 74.[19]

Attitudes

Talking after his retirement of the lack of planning in the early days in East Africa, Mitchell said "there was no colonial policy, for Secretaries of State changed every eighteen months or so; so no one ever disciplined a Governor and no Secretary of State would ever force a row with settlers".[20] However, Mitchell had a paternalistic attitude towards Africans, considering that they needed help from white settlers to become civilised. In The Agrarian Problem in Kenya he said of Africans: "They are a people who, however much natural ability and however admirable attributes they may possess, are without a history, culture or religion of their own and in that they are, as far as I know, unique in the modern world.[21] Once progressive, by 1947 Mitchell had become highly conservative. In May that year he wrote to Arthur Creech Jones, Secretary of State for the Colonies, saying Britain's task was "to civilise a great mass of human beings who are at present in a very primitive moral, cultural and social state".[22]

References

- ↑ Frost 1992, p. 1.

- ↑ Collett 2003, p. 528.

- ↑ Mitchell 2012, pp. 123–124.

- ↑ Frost 1992, p. 2.

- 1 2 Frost 1992, pp. 2–4.

- ↑ Fisher 1988, pp. 52–53.

- 1 2 3 Lowry 2006, p. 59.

- 1 2 Frost 1992, p. 6.

- ↑ Frost 1992, p. 9.

- ↑ Schuknecht 2011, p. 273.

- ↑ Apter 1997, p. 208ff.

- ↑ Apter 1997, p. 223.

- ↑ Blaustein, Sigler & Beede 1977, p. 220.

- 1 2 Frost 1992, p. 158.

- 1 2 Frost 1992, p. 159.

- ↑ Frost 1992, pp. 159–160.

- ↑ Macdonald 2001, pp. 160–161.

- ↑ Kenya, A Preview...

- ↑ Frost 1992, p. 264.

- ↑ Karanja 2009, p. 43.

- ↑ Ogot & Ochieng 1995, p. 10.

- ↑ Muoria-Sal & Muoria 2009, p. 47.

Bibliography

- Apter, David Ernest (1997). The political kingdom in Uganda: a study of bureaucratic nationalism. Routledge. ISBN 0-7146-4696-2.

- Blaustein, Albert P.; Sigler, Jay A.; Beede, Benjamin R. (1977). Independence documents of the world, Volume 1. Brill Archive. ISBN 0-379-00794-0.

- Collett, Mike (2003). The Complete Record of the FA Cup. Sports Books. ISBN 1-899807-19-5.

- Fisher, Barbara (1988). Joyce Cary remembered: in letters and interviews by his family and others. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-389-20812-4.

- Frost, Richard (1992). Enigmatic proconsul: Sir Philip Mitchell and the twilight of empire. The Radcliffe Press. ISBN 1-85043-525-1. Retrieved 12 April 2011.

- Karanja, James (2009). The Missionary Movement in Colonial Kenya: The foundation of Africa Inland Church. Cuvillier Verlag. ISBN 3-86727-856-3.

- "Kenya, A Preview of Royal Duties". Life. 32 (7). 18 February 1952. ISSN 0024-3019.

- Lowry, Robert (2006). Fortress Fiji: holding the line in the Pacific War, 1939–1945. Robert Lowry. ISBN 0-9775129-0-8.

- Macdonald, Barrie (2001). Cinderellas of the Empire: towards a history of Kiribati and Tuvalu. [email protected]. ISBN 982-02-0335-X.

- Mitchell, Andy (2012). First Elevens: The Birth of International Football. Andy Mitchell Media. ISBN 978-1475206845.

- Muoria-Sal, Wangari; Muoria, Henry (2009). Writing for Kenya: the life and works of Henry Muoria. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-17404-4.

- Ogot, Bethwell A.; Ochieng, William Robert (1995). Decolonization and independence in Kenya. Ohio State University Press. ISBN 0-8214-1051-2.

- Schuknecht, Rohland (2011). British Colonial Development Policy After the Second World War: The Case of Sukumaland, Tanganyika. LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 3-643-10515-0.