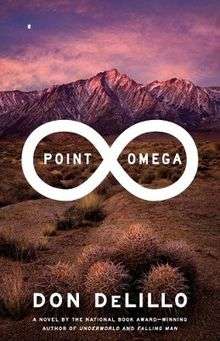

Point Omega

First edition | |

| Author | Don DeLillo |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Scribner |

Publication date | 2010 |

| Media type | Print (hardback) |

| Pages | 117 |

| ISBN | 978-1-4391-6995-7 |

| 813/.54 22 | |

| LC Class | PS3554.E4425 P65 2010 |

| Preceded by | Falling Man |

Point Omega is a short novel by the American author Don DeLillo that was published in hardcover by Scribner's on February 2, 2010. It is DeLillo's fifteenth novel published under his own name and his first published work of fiction since his 2007 novel Falling Man.

Plot

According to the Scribner 2010 catalog[1] made available on October 12, 2009, Point Omega concerns the following:

In the middle of a desert "somewhere south of nowhere," to a forlorn house made of metal and clapboard, a secret war advisor has gone in search of space and time. Richard Elster, seventy-three, was a scholar - an outsider - when he was called to a meeting with government war planners. This was prompted by an article he wrote explicating and parsing the word "rendition". They asked Elster to conceptualize their efforts - to form an intellectual framework for their troop deployments, counterinsurgency, orders for rendition. For two years he read their classified documents and attended secret meetings. He was to map the reality these men were trying to create "Bulk and swagger," he called it. He was to conceptualize the war as a haiku. "I wanted a war in three lines..."

At the end of his service, Elster retreats to the desert, where he is joined by a filmmaker intent on documenting his experience. Jim Finley wants to make a one-take film, Elster its single character - "Just a man against a wall."

The two men sit on the deck, drinking and talking. Finley makes the case for his film. Weeks go by. And then Elster's daughter Jessie visits - an "otherworldly" woman from New York - who dramatically alters the dynamic of the story. Jessie is strange and detached but Elster adores her. Elster explains how she is of high intelligence and remarks that she can determine what people are saying in advance of hearing the words by reading lips. Jim is sexually drawn to her but nothing happens except his watching her as a voyeur would. After the most pointed of such behavior Jessie disappears without a trace. Line two of the haiku structure (see below) winds up with the disbelief and grieving over Jessie; there are attempts to find her; there are references to a boyfriend or acquaintance named (maybe) Dennis. Jessie's mother had sent her to the desert to get away from this man. In light of this devastating event, all the men's talk, the accumulated meaning of conversation and connection, is thrown into question. What is left is loss, fierce and incomprehensible.[1]

The novel is structured like a haiku to provide the illusion of self-contained meaning. Lines one and three take place on September 3 and then September 4. The viewpoint is that of an anonymous man watching a work of conceptual art (24 Hour Psycho) that involves Psycho slowed down, broken down so that it takes 24 hours to play. The man mostly stands against a wall in the exhibition room and obsesses about the details and concepts of the work in hopes of willfully losing himself in Psycho (a kind of self-rendition). He attends the exhibition every day, all day. In Line one, Elster and Jim make a brief appearance. The man assumes they are academics, film critics and doesn't understand why they leave so quickly. In Line two, we meet Jim and Elster and the main "action" of the novel takes place (temporally after Lines one and three). Jim is a filmmaker obsessed with the medium. His one previous work was, as his estranged wife remarked, a film about an idea. It seems to involve a pastiche of Jerry Lewis in performance mode at his famous telethons. Only Jerry Lewis appears in the film; only Elster will appear in the film Jim proposes to him. Elster refuses to agree to the idea but strings Jim along out in the desert where he does reveal a little about his intellectual provenance including his study of Teilhard de Chardin (whose principle idea is of a universe moving toward greater complexity and consciousness).

In Line three, Jessie goes to the Psycho exhibit and meets the man on the wall. She tells him her father recommended the exhibit. We already know that Jim recommended it to Elster and took him to the exhibit. The man on the wall tries to arrange a date with Jessie. He gets her phone number but not her name. Line three ends with the man returning to the exhibit.

The direction of the novel is the opposite of movement toward greater complexity and consciousness. It is toward a self-contained, self-defining and blind will to power. That is the idea behind the government's notion of war as haiku. Elster's parsing of the word rendition is no different from Psycho in slo-mo: murder disassociated from its reality by clinical and abstract analysis. The novel's central metaphor is autism. The man on the wall (in either manifestation) and Jessie are obviously symptomatic. Jim and Elster are no better. The signs are there: Jerry Lewis, Psycho in slo-mo, war as haiku, the desert with Elster's solace in it as signifier for total annihilation, the word rendition.

There are clear parallels to Thomas Pynchon especially in Gravity's Rainbow. In Pynchon the tension balances along the relationship between knowledge (greater complexity?) and a death instinct; capitalism or western civilization as a death cult. In Point Omega the movement toward annihilation (rendition) is symptomatic of a defect or disturbance in mental process.

In his review for Publishers Weekly, Dan Fesperman revealed that the Finley character is "...a middle-aged filmmaker who, in the words of his estranged wife, is too serious about art but not serious enough about life" and compares Elster to "a sort of Bush-era Dr. Strangelove without the accent or the comic props".[2] Writing for the Wall Street Journal, Alexandra Altar described the novel as "...a meditation on time, extinction, aging and death, subjects that Mr. DeLillo seldom explored in much depth as a younger writer."[3]

Promotion and publicity

DeLillo made a series of rare public appearances in the run up to the release of Point Omega throughout September, October, and November 2009 and is set to do more press publicity upon the novel's release.[4] One of these appearances was a PEN event in New York, 'Reckoning with Torture: Memos and Testimonies from the "War on Terror"'. This event was "an evening of readings and response, [with Members and friends of PEN read[ing] from the recently-released secret documents that have brought these abuses to light - memos, declassified communications, and testimonies by detainees - and will reflect on how [America] can move forward as a nation."[4] An original short story unrelated to Point Omega entitled "Midnight in Dostoevsky" appeared in the November 30 edition of The New Yorker.[5] An extract from Point Omega was made available on the Simon and Schuster website on December 10, 2009.[6] DeLillo is set to give a first public reading of Point Omega at Book Court in Brooklyn, New York at 7pm on February 11, 2010.[7]

DeLillo made an unexpected appearance at a PEN event on the steps of the main branch of the New York City Public Library in support of Chinese dissident writer Liu Xiaobo, who was sentenced to eleven years in prison for "inciting subversion of state power" on December 31, 2009.[8]

Point Omega spent one week on the New York Times Bestseller List, peaking at #35 on the extended version of the list during its one-week stay on the list.[9]

Reception

On the whole, reviews for Point Omega have been positive.[10]

An early mostly positive review appeared on the website of Publishers Weekly on December 21, 2009.[2] Reviewer Dan Fesperman praised the novel's style, stating that while "it's hardly a new experience to emerge from a Don DeLillo novel feeling faintly disturbed and disoriented ... DeLillo's lean prose is so spare and concentrated that the aftereffects are more powerful than usual".[2] Fesperman goes on to add that DeLillo "... is at his best rendering micro-moments of the inner life, and "laying bare the vanity of intellectual abstraction."[2] However, Fesperman writes that there are occasions when "... the going gets a little tedious",[2] and he compares the novel to a "brisk hike up a desert mountain — a trifle arid, perhaps, but with occasional views of breathtaking grandeur."[2]

Further praise came from the literary review Kirkus, with its reviewer declaring the novel to be "an icy, disturbing and masterfully composed study of guilt, loss and regret - quite possibly the author's finest yet."[11] The Kirkus review further praised the novel's narrative as "crisp, precisely understated, [and] hauntingly elliptical";[11] approvingly drawing comparisons between Point Omega and Albert Camus' novella The Fall;[11] and that with this novel, DeLillo had moved "... a step beyond the disturbing symbolism of Falling Man".[11]

As with the Publishers Weekly review, Leigh Anne Vrabel's review for Library Journal highlighted the quality of DeLillo's prose, stating that it is "... simultaneously spare and lyrical, creating a minimalist dreamworld that will please readers attuned to language and sound."[11] Vrabel also praised the narrative of the novel, writing that "structural purists ... will appreciate the novel's film-related framing device, which wraps around the main action like a blanket and unifies the whole with a painful, poignant grace."[11] The only slightly negative remark regards the novel's brevity, but the overall conclusion was highly positive: "though it be but brief, DeLillo's latest offering is fierce. An excellent nugget of thought-provoking fiction that pits life against art and emotion against intellect."[11]

There were also negative notices from such publications as New York, The National and Esquire.[12]

In his mostly negative review for New York magazine's books section, Sam Anderson struck a note of disappointment, puzzlement, and confusion. In Anderson's opinion, Point Omega is "[the latest of a] recent stretch of post-Underworld metaphysical anti-thrillers—The Body Artist, Cosmopolis, Falling Man—[showing DeLillo's writing] has reached a whole new level of [narrative] inertia".[13] For Anderson, the novel's "glacial aesthetic"[14] and seemingly slow moving non-plot of the novel is a major fault: "the closest the book comes to real action is when Elster’s daughter shows up—although “shows up” is a strong phrase to use for a character who hardly seems to exist at all. When she disappears, mysteriously — the only major event of the novel — it seems like a formality."[13] The experience of reading a "late-phase DeLillo" novel, according to Anderson, makes him "... feel like a late-phase DeLillo character: distant, confused, catatonic, drifting into dream worlds, missing dentist appointments, forgetting the meanings of basic words, and staring at everyday objects as if they were holy relics."[13] However, Anderson admits that "this disorientation might explain why I can’t quite make up my mind about Point Omega",[13] suggesting some positives and elaborating that "the strongest material in Point Omega is only tangentially related to the book’s main story, and is essentially just art criticism"[13] (referring to the bracketing chapters that begin and end the book). Anderson further remarks on the novel's style: "DeLillo is, after Beckett and Robbe-Grillet, the indisputable master of grinding a plot to the brink of stasis and then recording its every last movement. Point Omega seems like a logical endpoint of that quest."[13] But Anderson goes on to ask with some concern, "how much further into the desert of plotlessness is DeLillo willing to go, and how far are we willing to follow? Where else can he possibly take the novel?"[13] Anderson finally concludes on a negative note: "I get the sense that he wants his oeuvre to culminate in a pure act of attention, and I’m not convinced that the novel is the best medium in which to do that. As a raging DeLillo fan, I’d be more excited to see him branch out to another genre—an experimental autobiography, or essayistic micro-observations of his favorite art and literature—than write another short novel about detached and largely interchangeable characters."[13]

Writing for the "Friday Review" section of The National, Giles Harvey - like Anderson's review in New York - made much criticism of the stylistic tendencies of what could be termed as 'Late DeLillo', arguing that "... since the epochal 1997 masterpiece Underworld ... DeLillo’s books have come to seem lopsided, top-heavy: dense with cerebration but humanly thin."[15] At his best, Harvey writes, "when [DeLillo] is...sending us dispatches from the front lines of contemporary experience ... DeLillo has few obvious betters. By comparison, most of his peers seem 50 miles back, in the hermetic opulence of some requisitioned château."[15] However, in Point Omega, Harvey feels that DeLillo "... fails to make his characters more than ciphers for his ideas."[15] Much of Harvey's criticism concerns the protagonists and characterisation. Of the retired war planner Elster, Harvey draws comparisons to Bill Gray in DeLillo's Mao II and Lee Harvey Oswald in Libra,[15] but criticises DeLillo's characterisation for making Elster seem "... less a human being than a vague aggregate of ideas."[15] Harvey goes on, "what’s missing from DeLillo’s presentation of human beings ... is emotional depth."[15] Aside from the weak characterisation, the typical DeLillo black comedy appears to be watered down and a distilled re-reun of the humour from DeLillo's previous novels. The conversations that occur between Elster and his would-be documenter Jim Finley in the main body of the novel "... can sometimes be quite funny (although not nearly as funny as the screwball conversations on similar themes in Players or White Noise)".[15] Further, Harvey finds fault with how, as he argues, "Point Omega was presumably conceived of as an emotional education – a story about a coldly intellectual man whose daughter’s disappearance leads him to recognise the limits of the intellect and his own human fallibility ... It is indicative of DeLillo’s failure that he should feel the need to state so baldly the novel’s intended emotional arc."[15]

References

- 1 2

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Fiction Book Reviews: 12/21/2009 - 2009-12-21 07:00:00". Publishers Weekly. Archived from the original on January 19, 2010. Retrieved 2010-03-18.

- ↑ Alter, Alexandra (2010-01-30). "Don DeLillo on Point Omega and His Writing Methods - WSJ.com". Online.wsj.com. Retrieved 2010-03-18.

- 1 2 "Don DeLillo - Events of Interest". Perival.com. Retrieved 2010-03-18.

- ↑ Don DeLillo (2009-01-07). "Midnight in Dostoevsky". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2010-03-18.

- ↑ "Books : Point Omega : Excerpts". Books.simonandschuster.com. Retrieved 2010-03-18.

- ↑ EVENTS. "Events « BookCourt". Bookcourt.org. Retrieved 2010-03-18.

- ↑ "PEN American Center - Writers Rally for Release of Liu Xiaobo". Pen.org. 2009-12-31. Retrieved 2010-03-18.

- ↑ Schuessler, Jennifer (2010-02-18). "TBR - Inside the List". NYTimes.com. Retrieved 2010-03-18.

- ↑ Point Omega Media Watch - a novel by Don DeLillo - 2010

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Point Omega, Don DeLillo, Book - Barnes & Noble". Search.barnesandnoble.com. Retrieved 2010-03-18.

- ↑ Benjamin Alsup, "Somebody Please Get Don DeLillo a Drink", Vanity Fair, January 27, 2010

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Sam Anderson on 'Point Omega' by Don DeLillo - New York Magazine Book Review". Nymag.com. 2010-02-01. Retrieved 2010-03-18.

- ↑ Anderson, Sam (2010-01-24). "Sam Anderson on 'Point Omega' by Don DeLillo - New York Magazine Book Review". Nymag.com. Retrieved 2010-03-18.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Missing persons from Don DeLillo - The National Newspaper". Thenational.ae. 2010-01-28. Retrieved 2010-03-18.