Prison gang

A prison gang is an inmate organization that operates within a prison system. It has a corporate entity and exists into perpetuity. Its membership is restrictive, mutually exclusive, and often requires a lifetime commitment.[1] Prison officials and others in law enforcement use the euphemism "security threat group" (or "STG"). The purpose of this name is to remove any recognition or publicity that the term "gang" would connote when referring to people who have an interest in undermining the system.

Origins

The convict code and informal governance of prisons

Before the rise of large, formal prison gangs, political scientists and researchers found that inmates had already organized around an understood "code" or set of norms. For example, political scientist Gresham Sykes in The Society of Captives, a study based on the New Jersey State Prison, claims that "conformity to, or deviation from, the inmate code is the major basis for classifying and describing the social relations of prisoners".[2] Prisoners achieved a social equilibrium around unwritten rules. The code may include an understanding of jail yard territory based on rank or ethnicity, or it could simply be loyalty between inmates and against guards. Sykes writes that an inmate may "bind himself to his fellow captives with ties of mutual aid, loyalty, affection, and respect, firmly standing in opposition to the officials."[2] Hostility between wardens and prisoners, restrained freedom, and ,some argue, the lack of access to heterosexual relationships shaped prison social environment and political dynamics.

Rising prison populations and the emergence of formal gangs

When researchers or political scientists discuss "classic prison gangs," they are referring to prison gangs in the United States, which began to form in the mid 1960s.[1] Around this time, across the prison system, there was a large increase in prison population.[3]

As prison populations grew, the informal convict code was no longer enough to coordinate and protect inmates. The constant surge of prisoners coming into the system with no understanding of the status quo had disrupted the established equilibrium cohesion. And as demographics inside prisons changed drastically, small groups centered on ethnicity, race, and pre-prison alliances were disrupted. John Irwin states in his book, Prisons in Turmoil, that by 1970 "there [was] no longer a single, overarching convict culture."[4]

Furthermore, as the prison population grew so did the consumer base for contraband items, not only drugs and weapons but also items that are legal outside of prison but are illegal to trade within prisons, such as money, alcohol, tattoos, etc. Several challenges arose that destabilized the socio-political system of self-enforced cooperation that had existed under the convict code. These new conditions posed complications to consumer-supplier relationships in the already distrustful environment of an underground economy. It became more and more difficult for independent individual suppliers to accommodate this increased demand. Under tight prison security and limited means, these individual suppliers could only provide a limited amount of product. Their consumer base was too small for them to establish a "brand" or credibility themselves. New consumers would have to buy products of unknown quality and bear the risk of the supplier being an undercover informant and even the possibility that he would not deliver at all.

The ever-fluctuating inmate population also provided a dangerous market in which to operate. Individual suppliers had to protect themselves from possible murder and assault by consumers and other suppliers, as well as ensure that their products would not be confiscated or stolen. They were vulnerable to those who delivered and carried the contraband into the prison, and they bore the risk of consumers not paying for the product, or if given on credit, not paying the loan. The consumers could also be informants.

In legal markets, the government accounts for these risks by means of contract enforcement and property rights. Prison gangs formed in order to step into this role and fill in the power vacuum.[5] They vet and manage tax-paying supplier gangs within prisons, regulate transactions, and control violence in the marketplace and on the streets.

Prison gangs are effective in governing markets. They provide protection to their member suppliers more effectively than individual suppliers could do for themselves. They carry the credible threat of exercising violence, and even murder in case of theft or snitching, to ensure timely payments. They protect their members against competing suppliers. The size of prison gangs and their scale of product supply also means that they have a broad scope of knowledge about their client base. They share information on informants or inmates that default on payments. This scope of supply also gains a reputation with consumers who can then feel safe in being able to gauge the quality of product and credibility of suppliers.[1]

A crucial difference between individual suppliers who operate under the convict code and prison gangs is the time frame in which they operate. Unlike individual suppliers that cycle in and out, prison gangs form long-term institutions, regardless of how often members enter or leave the system. There are always plenty of members to maintain the gang's functions behind bars and on the streets. This means they have solid incentive to provide quality product to uphold a good reputation in the long run.

Prison gangs have evolved into complex organizations with hierarchies and vote-based ranks and intricate coalitions with exclusive and many times permanent memberships.

Alternative factors and explanations

Another approach to understanding prison gang development is based upon observations of inmates in the Texas prison system. It provides a five stage progression from an inmate's entrance to the prison to the formation of a prison gang.[6] First an inmate enters the prison, alone and thus fearful until he finds a sense of belonging in a "clique of inmates." They band together without formal rules, leaders, or membership requirements. It then evolves into a "predatory group," creating exclusive requirements for membership and positioning itself against wardens, even assaulting them. Then, by engaging in illegal activities, they choose leaders to manage them. In its final stage the group emerges as a prison gang.

A gendered approach to prison gangs offers two arguments focusing on the idea of male domination and the inmate's adherence to a hyper-masculine ideal.

One argument claims that prison order is shaped by the inmates' desire or need for male domination, and the gang reconstructs this sense of power in prison.[7] As inmates can no longer "subjugate women," they find other forms of domination, resorting to force and violence to control each other.

Another approach, discussed by Erving Goffman, maps out four steps of inmate adaptation. In the first step, the inmate undergoes a "situational withdrawal" or mental withdrawal from the institution. "The inmate withdraws apparent attention from everything except events immediately around his body." The second step is called "colonization" when the inmate tries to rationalize the institution as preferable to life on the outside. The third step, "conversion," is when "the inmate takes over the staff's view of himself and tries to act out the role of the perfect inmate." The fourth step, which prison gang members fit into, is called "the intransigent line," when the inmate refuses the authority of the institution and acts against it.[8]

There are also two prominent sociological theories surrounding prison gangs and the order within prisons: deprivation theory and importation theory.

Deprivation theory argues that social order within prisons arises due to the pain of imprisonment; studies focusing on this theory examine the experiences of prisoners and the nature of their confinement.

Importation theory focuses instead on experiences prisoners had prior to incarceration. It explores the ways in which class, race, and drug culture outside the prison have shaped dynamics inside the prison.[1]

Operations and activities

Since prison gangs gain a long-term profit if transactions in the illicit market run smoothly, they have the incentive to ensure that there is order and cohesion between suppliers and consumers.

Like stationary bandits that exist under anarchy in the model presented by economist Marcur Olson,[9] prison gangs are actors who gain if they can extort some profit from the product that street gangs exchange inside and outside of prisons. They act to maximize their profit, not only by restraining the amount they extort, but also by trying to increase the produce.

In the process of maximizing profit, gangs may provide public goods to ensure smooth production, such as working to resolve gang disputes inside and outside of the prison.

Moreover, by holding the monopoly on violence in prisons, they pose a credible threat to street gangs, which they leverage to extort their profits. So prison gangs can extort street gangs because they pose a credible threat to inmates in the county jail, and street gang members rationally anticipate spending time there. They effectively use incarcerated street gang members as hostages to force non-incarcerated gang members to pay. Furthermore, they can encourage street gangs to steal from and make war with other non-taxpaying street gangs.

However, prison gangs cannot extort drug dealers whom they cannot harm in jail; for American prison gangs this usually means members of other races (the county jails segregate them based upon race). They also cannot extort taxes from people who do not anticipate incarceration, because there is no threat of facing violence in prison. And they cannot tax those outside the jurisdiction of a jail controlled by the gang. Non-incarcerated prison gang members collect taxes and regulate fraud and imposters acting as tax collectors. Taxpayers also ensure that their money is going to the right hand because consequences otherwise would be severe.

Political scientist David Skarbeck writes, "Like the stationary bandit, prison gangs provide governance institutions that allow illicit markets to flourish. They adjudicate disputes and protect property rights. They orchestrate violence so that it is relatively less disruptive. They do not do this because they are benevolent dictators but because they profit from doing so. In addition to governing prisons, gangs are also an important source of governance to the criminal world outside of prison. They wield tremendous power over street gangs, specifically those participating in the drug trade. Because of this power, governance from behind bars helps illicit markets to flourish on the streets."[1]

The way they prison gangs consolidate and maintain power is also comparable to how actors behave in Charles Tilly's predatory theory of state building model.[10] Prison gangs engage in "war making," or monopolizing on force and occupying the power vacuum of state authority. They eliminate rivals (in the US mostly along racial lines) within their territories, and in doing so they carry out "state making." Gangs offer protection to their members, affiliates, and clients. They also extract or collect taxes from client gangs and those in the trade to maintain and expand their system.

Organization and structure

Prison gangs work to recruit members with street smarts and loyalty, and they look for inmates who will be able to carry out the gangs' functions and exercise force when necessary. They also create a structure to monitor activities of members and regulate the behavior of existing members within the gangs to ensure internal cohesion.

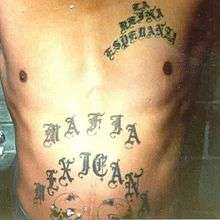

To ensure that high quality, dedicated members are being recruited, many prison gangs rely on existing members to vouch for or refer new members into the group. To enter gangs, members often have to prove their loyalty through costly activity, often violent hazing. Gang members mark themselves as part of the gang with tattoos (or colors, on the streets) so that taxpayers know they are credible collectors and so that gangs can keep track of their members as they move in and out of prison.

Prison gangs maintain a hierarchy and have written and unwritten rules of conduct. They have constitutions to define expectations and to guide laws for those they govern as well as to direct the process for the creation of new rules. In terms of the hierarchy, at the top of most US prison gangs is a group of "shot callers" who are like major stakeholders that make the major decisions about operations. Having a single dictator-like shot caller is unusual. Checks and balances within prison gang organizations are lucrative; internally, there ways to voice dissatisfaction towards any level of the organization. For example, when conflicts arise or abuses occur where a higher-ranked gang member commits an offense against a lower-ranked member, an internal court-like body receives complaints and determines punishments. Actions are punished with violence. In many gangs exit is not an option (or is a very costly one); many prison gangs require a lifetime membership.[1]

Political scientist Ben Lessing differentiates between prison gangs that arise within the prison system, which he calling 'natives,' and those that were already formed outside, calling them 'imports'.[11] He claims that norms and culture-like initiation rituals, rules about sex, and relations with guards and non-members are shaped by the direction of formation. Natives have a 'prison character' in their imagery, traits, and codes that they retain even when native gangs engage in operations beyond the prison system. On the other hand, import gangs arrive with a "strong group identity, behavioral norms, and often their publicly known histories and reputations."[11] This gives these groups a stronger sense of solidarity and cohesion in prison, though they compensate in how they well they navigate the system within prison.[12] Imports have an advantage in their existing outside operations.

List of American prison gangs

Hispanic Prison gangs

La Eme or the Mexican Mafia: (Blue)"Eme" is the Spanish name of the letter "M," and it is the 13th letter in the alphabet. The Mexican Mafia is composed mostly of Hispanics, although there are some Caucasian members. The Mexican Mafia and the Aryan Brotherhood are allies. They work together to control prostitution, drug-running, weapons, and "hits" or murders. Eme was originally formed in the 1950s in California prisons by Hispanic prisoners from the southern part of that state. It has traditionally been composed of US-born and US-raised Hispanics and has retained ties to the Southern California-based "Sureños." During the 1970s and 1980s, Eme in California established the model of leveraging its power in prison to control and profit from criminal activity on the street.

Nuestra Familia: (Red) (family" in Spanish) "N," the 14th letter in the alphabet, along with the Roman numeral "XIV" is the symbol used to represent the gang. Nuestro Familia is another mostly Hispanic prison gang that is constantly at war with La Eme. It was originally formed by Northern-California- or rural-based Hispanic prisoners with ties to "Norteños" of Northern California, opposing domination by La Eme which was started by and associated with Los Angeles gang members. Nuestro Familia was first established California's Soledad Prison in the 1960s.[4]

The Texas Syndicate: A mostly Texas-based prison gang that includes mostly Hispanic members and does (albeit rarely) allow Caucasian members. The Texas Syndicate, more than La Eme or Nuestra Familia, has been associated or allied with Mexican immigrant prisoners, while Eme and Familia tend to be composed of and associate with US-born or US-raised Hispanics.

Ñetas: A Hispanic (mainly Puerto Rican) gang in Puerto Rico and on the eastern coast of the US. Originally formed in 1970 in Rio Pedras Prison, Puerto Rico.[5] African American[edit]

Black prison gangs

Most African-American prison gangs retain their street gang names and associations. These commonly include Rollin' sets (named after streets, i.e., Rollin' 30s, Rollin' 40s, etc.) that can identify with either Blood or Crip affiliations.

The Black Guerilla Family represents an exception. It was originally a politically based group with a significant presence in prisons and prison politics. It was founded in 1966 at San Quentin State Prison in California by former Black Panther member George L. Jackson.[6]

United Blood Nation: An African-American prison gang on the east coast. They are rivals with the Netas and have ties with the Black Guerilla Family.

Folk Nation: Found in Midwestern and Southern states, allied with Crips, bitter rivals with the People Nation.

People Nation: Found in Midwestern and Southern states, allied with Bloods, bitter rivals with the Folk Nation.

D.C. Blacks: Founded in Washington D.C. by African-American inmates, are allied with the Black Guerilla Family and United Blood Nation, and enemies to the Aryan Brotherhood and Mexican Mafia.

Conservative Vice Lords (CVL): A primarily African-American gang that originated in the St. Charles, Illinois Youth Center outside Chicago.[7] In Chicago, CVL operated primarily in the Lawndale section and used profits from drug sales to continue its operations and used prisons to train and recruit new members.[8]

White prison gangs

Aryan Brotherhood: A white prison gang that originated in California's San Quentin Prison amongst white American prisoners in 1964. Its emblem, "the brand," consists of a shamrock and the number 666. Other identifiers include the initials "AB," swastikas and the sigrune.[9] Perhaps out of their ideology and the necessity of establishing a presence among the more numerous Black and Hispanic gang members, the AB has a particular reputation for ruthlessness and violence. Since the 1990s, in part because of this reputation, the AB has been targeted heavily by state and federal authorities. Many key AB members have been moved to "supermax" control-unit prisons at both the federal and state level or are under federal indictment.

Nazi Lowriders: A newer white prison gang that emerged after many Aryan Brotherhood members were sent to the Security Housing Unit at Pelican Bay or transferred to federal prisons. NLR is associated with members originally from the Antelope Valley and is known to accept some light-skinned or Caucasian-identified Hispanic members.

European Kindred: A white supremacist prison gang founded in Oregon that is affiliated with the Aryan Brotherhood and the Ku Klux Klan.

Confederate Knights of America: A white supremacist prison gang in Texas that is affiliated with the KKK and the AB.

Aryan Circle: A white supremacist prison gang concerned about race before money.

Dead Man Incorporated (DMI): A predominantly white prison gang founded in the Maryland Correctional System, with branches in many other correctional facilities throughout the U.S.

Aryan Brotherhood of Texas: Despite the similarity of the name, the Aryan Brotherhood of Texas (A.B.T.) does not have ties with the original Aryan Brotherhood. Founded in Texas in the 1980s the A.B.T. was created mainly as a criminal enterprise.[10]

Brotherhood of Aryan Alliance (a. k. a. the "211's") [11]

International gangs

South Africa

Prominent prison gangs in South Africa: 26s, 27s and 28s, collectively known as the Numbers, originate from a gang called The Ninevites, in the 19th- and early 20th-century. It was born in Johannesburg, and the leader of the Ninevites, "Nongoloza" Mathebula, is said to have created laws for the gang. "Nongoloza" became a supernatural figure and left behind an origin myth that shapes the current laws of the Numbers.[13]

The gangs began to project outside the prison system starting in 1990, as globalization led to South Africa's illicit markets seeing the rise of large drug trafficking gangs. The Americans and the Firm, the two largest super gangs outside of prison made alliances with Numbers gangs. They imported imagery, laws, and parts of the Numbers's initiation system. Membership in these gangs is not determined by race as it is with US prison gangs, however, initiation is still a costly and violent process, sometimes involving sexual hazing.

Brazil

The Primeiro Comando da Capital (or the PCC) is a Brazilian prison gang based in Sao Paulo. The gang rose in 1993 at a soccer game at Taubate Penitentiary to fight for prisoners' rights in the aftermath of the 1992 Carandiru Massacre, when Sao Paulo state military police killed more than 100 inmates.[14]

The gang orchestrated rebellions in 29 Sao Paulo state prisons simultaneously in 2001, and since then it has caught the attention of the public for ensuing waves of violence. The Brazilian police and media estimate that at least 6,000 members pay monthly dues and are thus a base part of the organization. According to Sao Paulo Department of Investigation of Organized Crime, more than 140,000 prisoners are under their control in Sao Paulo.[14]

The gang does not allow mugging, rape, extortion, or the use of the PCC to resolve personal conflicts. It maintains a strict hierarchy, led by Marcos Willians Herbas Camacho. All members inside and outside are required to pay taxes. Members can be soldiers, towers (gang leaders in particular prisons), or pilots (who specialize in communications). The PCC has strong ties with the Red Command, Rio's most powerful drug-trafficking organization which is rumored to supply them with cocaine.[14]

Policy implications

Political scientist Benjamin Lessing predicts that crackdowns and harsher carceral sentences will increase prison gangs' control of outside actors, and that beyond a point, these policies limit state power. Lessing states, "the harsher, longer, and more likely a prison sentence, the more incentives outside affiliates have to stay on good terms with imprisoned leaders, and hence the greater the prison gangs' coercive power over those who anticipate prison."[15]

Chart 6.1 from this article in the Small Arms Survey[16] explores the effects of certain policy measures on the propagation of prison gangs through prison systems and their projection on streets.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Skarbek, David. The Social Order of the Underworld: How Prison Gangs Govern the American Penal System. : Oxford University Press, 2014-07-01.Oxford Scholarship Online. 2014-06-19. Date Accessed 7 May. 2016 <http://www.oxfordscholarship.com/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199328499.001.0001/acprof-9780199328499>.

- 1 2 Gresham M. Sykes, The Society of Captives: A Study of a Maximum Security Prison (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1958), 79.

- ↑ http://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/overtime.html

- ↑ Irwin, John. 1980. Prisons in Turmoil. Boston: Little, Brown

- ↑ Skaperdas, Stergios. "The Political Economy of Organized Crime: Providing Protection When the State Does Not." Conflict and Governance (2003): 163-92. Web.

- ↑ Buentello, Salvador, Robert S. Fong, and Ronald E. Vogel. 1991. "Prison Gang Development: A Theoretical Model." The Prison Journal 71(2): 3–14.

- ↑ Dolovich, Sharon. 2011. "Strategic Segregation in the Modern Prison" American Criminal Law Review 48(1): 1–110.

- ↑ Goffman, Erving, Asylums: Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates (London: Penguin, 1973) (first published in 1961).

- ↑ Mancur Olson, 2000. Power and Prosperity: Outgrowing Communist and Capitalist Dictatorships, Oxford University Press. Description and chapter-preview links. Foreign Affairs review

- ↑ Tilly, Charles (1990). Coercion, Capital, and European States, AD 990–1990. Cambridge, Mass., USA: B. Blackwell.ISBN 1-55786-368-7.)

- 1 2 Lessing, Benjamin. The Danger of Dungeons: Prison Gangs and Incarcerated Militant Groups. Small Arms Survey, Chapter 6 (http://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/overtime.html) 2010

- ↑ Jacobs, James B. 1974. 'Street Gangs behind Bars.' Social Problems, Vol. 21, No. 3, pp. 395–409. —. 1978. Stateville: The Penitentiary in Mass Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

- ↑ Steinberg, Jonny. "Nongoloza's Children: Western Cape Prison Gangs during and after Apartheid." Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation. Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation, July 2014. Web.

- 1 2 3 Hanson, Stephanie. "Brazil's Powerful Prison Gang." Council on Foreign Relations. Council on Foreign Relations, 26 Sept. 2006. Web. 08 May 2016

- ↑ Lessing, Benjamin. "How to Build a Criminal Empire from Behind Bars: Prison Gangs and Projection of Power *." (n.d.): n. pag. IZA Logo Institute for the Study of Labor. IZA Logo Institute for the Study of Labor, 5 May 2014. Web. 14) Steinberg, Jonny. "Nongoloza's Children: Western Cape Prison Gangs during and after Apartheid." Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation. Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation, July 2014. Web.

- ↑ http://www.smallarmssurvey.org/fileadmin/docs/A-Yearbook/2010/en/Small-Arms-Survey-2010-Chapter-06-EN.pdf