Quantum eraser experiment

In quantum mechanics, the quantum eraser experiment is an interferometer experiment that demonstrates several fundamental aspects of quantum mechanics, including quantum entanglement and complementarity.

The double-slit quantum eraser experiment described in this article has three stages:[1]

- First, the experimenter reproduces the interference pattern of Young's double-slit experiment by shining photons at the double-slit interferometer and checking for an interference pattern at the detection screen.

- Next, the experimenter marks through which slit each photon went, without disturbing its wavefunction, and demonstrates that thereafter the interference pattern is destroyed. This stage indicates that it is the existence of the "which-path" information that causes the destruction of the interference pattern.

- Third, the "which-path" information is "erased," whereupon the interference pattern is recovered. (Rather than removing or reversing any changes introduced into the photon or its path, these experiments typically produce another change that obscures the markings earlier produced.)

A key result is that it does not matter whether the eraser procedure is done before or after the photons arrive at the detection screen.[1][2]

Quantum erasure technology can be used to increase the resolution of advanced microscopes.[3]

Introduction

The quantum eraser experiment described in this article is a variation of Thomas Young's classic double-slit experiment. It establishes that when action is taken to determine which slit a photon has passed through, the photon cannot interfere with itself. When a stream of photons is marked in this way, then the interference fringes characteristic of the Young experiment will not be seen. The experiment described in this article is capable of creating situations in which a photon that has been "marked" to reveal through which slit it has passed can later be "unmarked." A photon that has been "marked" cannot interfere with itself and will not produce fringe patterns, but a photon that has been "marked" and then "unmarked" can thereafter interfere with itself and will cooperate in producing the fringes characteristic of Young's experiment.[1]

This experiment involves an apparatus with two main sections. After two entangled photons are created, each is directed into its own section of the apparatus. Anything done to learn the path of the entangled partner of the photon being examined in the double-slit part of the apparatus will influence the second photon, and vice versa. The advantage of manipulating the entangled partners of the photons in the double-slit part of the experimental apparatus is that experimenters can destroy or restore the interference pattern in the latter without changing anything in that part of the apparatus. Experimenters do so by manipulating the entangled photon, and they can do so before or after its partner has passed through the slits and other elements of experimental apparatus between the photon emitter and the detection screen. So, under conditions where the double-slit part of the experiment has been set up to prevent the appearance of interference phenomena (because there is definitive "which path" information present), the quantum eraser can be used to effectively erase that information. In doing so, the experimenter restores interference without altering the double-slit part of the experimental apparatus.[1]

A variation of this experiment, delayed choice quantum eraser, allows the decision whether to measure or destroy the "which path" information to be delayed until after the entangled particle partner (the one going through the slits) has either interfered with itself or not.[4] In delayed-choice experiments quantum effects can mimic an influence of future actions on past events. However, the temporal order of measurement actions is not relevant. [5]

The experiment

First, a photon is shot through a specialized nonlinear optical device: a beta barium borate (BBO) crystal. This crystal converts the single photon into two entangled photons of lower frequency, a process known as spontaneous parametric down-conversion (SPDC). These entangled photons follow separate paths. One photon goes directly to a detector, while the second photon passes through the double-slit mask to a second detector. Both detectors are connected to a coincidence circuit, ensuring that only entangled photon pairs are counted. A stepper motor moves the second detector to scan across the target area, producing an intensity map. This configuration yields the familiar interference pattern.

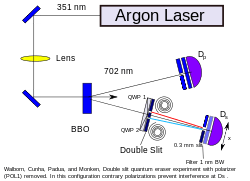

Next, a circular polarizer is placed in front of each slit in the double-slit mask, producing clockwise circular polarization in light passing through one slit, and counter-clockwise circular polarization in the other slit (see Figure 1). This polarization is measured at the detector, thus "marking" the photons and destroying the interference pattern (see Fresnel–Arago laws).

Finally, a linear polarizer is introduced in the path of the first photon of the entangled pair, giving this photon a diagonal polarization (see Figure 2). Entanglement ensures a complementary diagonal polarization in its partner, which passes through the double-slit mask. This alters the effect of the circular polarizers: each will produce a mix of clockwise and counter-clockwise polarized light. Thus the second detector can no longer determine which path was taken, and the interference fringes are restored.

A double slit with rotating polarizers can also be accounted for by considering the light to be a classical wave.[6] However this experiment uses entangled photons, which are not compatible with classical mechanics.

Non-locality

A very common misunderstanding about this experiment is that it may be used to communicate instantaneously information between two detectors. Imagine Alice on the first detector measuring either linear or circular polarization and instantaneously affecting the result of Bob's interference measurement. One could even conceive a situation in which Alice would switch from a circular polarizer to a linear polarizer on her detector long after Bob made his measurement: Bob's interference pattern would suddenly change from interference to a smear, but in the past! Following this train of thought would lead to an abundance of time paradoxes, like Bob measuring one pattern and telling Alice to switch her detector in the future to the polarizer that would cause the opposite pattern. So something must be wrong.

The misunderstanding is that Bob always measures a smear, never an interference pattern, no matter what Alice does. Non-locality manifests in a somewhat more subtle way. How? Let's say that the BBO crystal produces the following state:

(Alice's photon has clockwise polarization and Bob's photon has anti-clockwise polarization) or (Bob's photon has clockwise polarization and Alice's photon has anti-clockwise polarization)

If Alice places a circular polarizer in front of her detector that filters out photons with clockwise polarization, then every time Alice measures a photon, Bob's corresponding photon is sure to have a clockwise polarization:

Since Bob has placed opposite polarization filters on each slit, we know that these photons can only have passed through (let's say) the first slit. From that slit, they hit the screen according to the wave-function:

where a is the spacing between the slits, d is the distance from the slits to the screen and x is the distance to the middle of the screen. The intensity of light on the screen (counts of photons) will be proportional to the square of the amplitude of this wave, in other words

Likewise, when Alice measures a photon with anti-clockwise polarization, Bob receives an anti-clockwise polarized photon which can only pass through the second slit and arrives at the screen with a wave-function

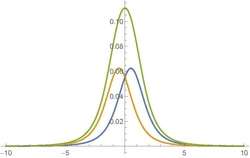

Notice that the only difference is the sign of a/2, because the photon was emitted from another slit. The pattern on the screen is another smear, but shifted by a. Now, this point is important: if Alice never tells him directly, then Bob never knows which polarization Alice measured, since both are produced in equal amounts by the crystal. So what Bob actually sees on his screen is the sum of the two intensities:

The results of this experiment are summarized in Fig.3. Bob can only distinguish the two peaks in his data after he got access to Alice's results: for the set of photons where Alice measured clockwise polarization, Bob's subset of photons is distributed according to and for the set of photons where Alice measured anti-clockwise polarization, Bob's subset of photons is distributed according to

Next, let Alice use a linear polarizer instead of a circular one. The first thing to do is write down the system's wave-function in terms of linear polarization states:

So say Alice measures a horizontally polarized photon. Then the wave function of Bob's photon is in a superposition of clockwise and anti-clockwise polarizations, which means indeed it can pass through both slits! After travelling to the screen, the wave amplitude is

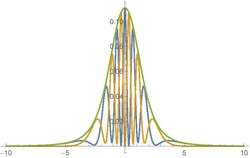

and the intensity is

where is the phase difference between the two wave function at position x on the screen. The pattern is now indeed an interference pattern! Likewise, if Alice detects a vertically polarized photon then the wave amplitude of Bob's photon is

and

and once again an interference pattern appears, but slightly changed because of the 180º phase difference between the two photons traversing each slit. So can this be used by Alice to send a message to Bob, encoding her messages in changes between the two types of patterns? No! Remember that, as before, if Bob is not told which polarization Alice measured, then all he sees is the sum of both patterns. The result is therefore,

which is again a smudge. The results are given in Fig.4.

So what's so odd about this experiment? The correlations change according to which experiment was conducted by Alice. Despite the fact that the total pattern is the same, the two subsets of outcomes give radically different correlations: if Alice measured a linear polarization the total smear is subdivided into two interference patterns whereas if Alice measured a circular polarization the pattern is the sum of two other Gaussian bell-shapes. How could Bob's photon know that it could go in the forbidden stripes of the interference pattern when Alice was measuring a circular polarization but not when Alice was measuring a linear one? This can only be orchestrated by a global dynamic of the system as a whole, it cannot be locally carried by each photon on its own. This experiment demonstrates the phenomenon of microscopic non-locality.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Walborn, S. P.; et al. (2002). "Double-Slit Quantum Eraser". Phys. Rev. A. 65 (3): 033818. arXiv:quant-ph/0106078

. Bibcode:2002PhRvA..65c3818W. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.65.033818.

. Bibcode:2002PhRvA..65c3818W. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.65.033818. - ↑ Englert, Berthold-Georg (1999). "REMARKS ON SOME BASIC ISSUES IN QUANTUM MECHANICS" (PDF). Zeitschrift für Naturforschung. 54 (1): 11–32. Bibcode:1999ZNatA..54...11E. doi:10.1515/zna-1999-0104.

- ↑ Aharonov, Yakir; Zubairy, M. Suhail (2005). "Time and the Quantum: Erasing the Past and Impacting the Future". Science. 307 (5711): 875–879. Bibcode:2005Sci...307..875A. doi:10.1126/science.1107787. PMID 15705840.

- ↑ Yoon-Ho, Kim; Yu, R.; Kulik, S.P.; Shih, Y.H.; Scully, Marlan (2000). "A Delayed Choice Quantum Eraser". Physical Review Letters. 84: 1–5. arXiv:quant-ph/9903047

. Bibcode:2000PhRvL..84....1K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.84.1.

. Bibcode:2000PhRvL..84....1K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.84.1. - ↑ Ma, Xiao-song; Kofler, Johannes; Zeilinger, Anton (2016). "Delayed-choice gedanken experiments and their realizations". Rev. Mod. Phys. 88 (1): 015005. arXiv:1407.2930

. Bibcode:2016RvMP...88a5005M. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.88.015005.

. Bibcode:2016RvMP...88a5005M. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.88.015005. - ↑ Chiao, R Y; Kwia, P G; Steinberg, A M (June 1995). "Quantum non-locality in two-photon experiments at Berkeley". Quantum and Semiclassical Optics: Journal of the European Optical Society Part B. 7 (3): 259–278. arXiv:quantph/9501016

. Bibcode:1995QuSOp...7..259C. doi:10.1088/1355-5111/7/3/006.

. Bibcode:1995QuSOp...7..259C. doi:10.1088/1355-5111/7/3/006.

External links

- A more technical analysis of the quantum eraser experiment

- A Scientific American article: A Do-It-Yourself Quantum Eraser - note: SciAm online subscribers only

- but here they let you see the images for free.

- Demystifying the Delayed Choice Experiments