RMS Titanic in popular culture

The RMS Titanic has played a prominent role in popular culture since her sinking in 1912, with the loss of over 1500 of the 2200 lives on board. The disaster and the Titanic herself have been objects of public fascination for many years. They have inspired numerous books, plays, films, songs, poems, and works of art. The ship's story has been interpreted in many overlapping ways, including as a symbol of technological hubris, as basis for fail-safe improvements, as a classic disaster tale, as an indictment of the class divisions of the time, and as romantic tragedies with personal heroism. It has inspired many moral, social and political metaphors and is regularly invoked as a cautionary tale of the limitations of modernity and ambition.

Themes

Titanic has been commemorated in a wide variety of ways in the century since she sank in the North Atlantic Ocean in 1912. As D. Brian Anderson has put it, the sinking of Titanic has "become a part of our mythology, firmly entrenched in the collective consciousness, and the stories will continue to be retold not because they need to be retold, but because we need to tell them."[1]

The intensity of the public interest in the Titanic disaster in its immediate aftermath can be attributed to the deep psychological impact that it had on the public, particularly in the English-speaking world. Wyn Craig Wade comments that "in America, the profound reaction to the disaster can be compared only to the aftermath of the assassinations of Lincoln and Kennedy ... the entire English-speaking world was shaken; and for us, at least, the tragedy can be regarded as a watershed between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries."[2] John Wilson Foster characterises the sinking as marking "the end of an era of confidence and optimism, of a sense of a new departure."[3] Just two years later, what Eric Hobsbawm referred to as "the long nineteenth century" came to an end with the outbreak of the First World War.[4]

There have been three or four major waves of public interest in Titanic in the later part of the 20th century. The first came immediately after the sinking, but ended abruptly a couple of years later due to the outbreak of World War I, which was a far bigger and much more immediate concern for most people. The second came with the publication of Walter Lord's book A Night to Remember in 1955. The discovery of the wreck of the Titanic by Robert Ballard in 1985 sparked a new wave of interest which has continued to the present day,[3] boosted by the release of James Cameron's film of the same name in 1997. The fourth and final came with the capsizing of the Costa Concordia in 2012, just few months before the centenary of the Titanic disaster.

Even at the time, the high level of public interest in the disaster produced strong dissenting reactions in some quarters. The novelist Joseph Conrad (who was himself a retired sailor) wrote: "I am not consoled by the false, written-up, Drury Lane [theatrical] aspects of that event, which is neither drama, nor melodrama, nor tragedy, but an exposure of arrogant folly."[5] As Foster points out, however, Titanic herself can be seen as a stage, with her rigid segregation between the classes and the ersatz historical architecture of her interiors. The maiden voyage itself had theatrical overtones; the advance publicity highlighted the historic nature of the maiden voyage of the world's largest ship, and a substantial number of passengers were aboard specifically for that occasion. The passengers and crew can be viewed as archetypes of stock roles, which Foster summarises as "Rich Man, Socialite, Unsung Hero, Coward, Martyr, Deserter of Post, Stayer at Post, Poor Emigrant, Manifest Hero, etc."[3]

In such interpretations, the story of the Titanic can be seen as a kind of morality play. An alternative view, according to Foster, sees the Titanic as somewhere between a Greek and an Elizabethan tragedy; the theme of hubris, in the form of wealth and vaingloriousness, meeting an indifferent Fate in a final catastrophe is very much one that is drawn from classical Greek tragedies. The story also matches the template for Elizabethan tragedians with its episodes of heroism, comedy, irony, sentimentality and ultimately tragedy. In short, the fact that the story can so easily be seen as fitting an established dramatic template has made it hard not to interpret it that way.[6]

Describing the disaster as "one of the most fascinating single events in human history," Stephanie Barczewski identifies a number of factors behind the continuing popularity of the Titanic's story. The creation and destruction of the ship are symbols of "what human ingenuity can achieve and how easily that same ingenuity can fail in a brief, random encounter with the forces of nature." The human aspects of the story are also a source of fascination, with different individuals reacting in very different ways to the threat of death – from accepting their fate to fighting for survival. Many of those aboard had to make impossible choices between their relationships: stay aboard with husbands and sons or escape, possibly alone, and survive but face an uncertain future. Above all, Barczewski concludes, the story serves to jolt people out of hubristic complacency: "at its heart [it is] a story that reminds us of our limitations."[7]

The disaster has been called "an event that in its tragic, clockwork-like certainty stopped time and became a haunting metaphor"[1] – not just one metaphor but many, which the cultural historian Steven Biel describes as "conflicting metaphors, each vying to define the disaster's broader social and political significance, to insist that here was the true meaning, the real lesson."[8] The sinking of the Titanic has been interpreted in many ways. Some viewed it in religious terms as a metaphor for divine judgement over what they saw as the greed, pride and luxury on display in the ship. Others interpreted it as a display of Christian morality and self-sacrifice among those who stayed aboard so that women and children might escape. It could be seen in social terms as conveying messages about class or gender relations. The "women and children first" protocol seemed to some to affirm a "natural" state of affairs with women subordinated to chivalrous men, a view that campaigners for women's rights rejected. Some saw the self-sacrifice of millionaires like John Jacob Astor and Benjamin Guggenheim as a demonstration of the generosity and moral superiority of the rich and powerful, while the very high level death toll among Third Class passengers and crew members was seen by others as a sign of the working classes being neglected. Many believed that the conduct of the mainly Anglo-American passengers and crew demonstrated the superiority of "Anglo-Saxon values" in a crisis. Still others viewed the disaster as the result of the arrogance and hubris of the ship's owners and the Anglo-American elite, or as a demonstration of the folly of putting one's trust in technology and progress. Such a wide range of interpretations has ensured that the disaster has been the subject of popular debate and fascination for decades.[9]

Poems

The Titanic disaster led to a flood of verse elegies in such quantities that the American magazine Current Literature commented that its editors "do not remember any other event in our history that has called forth such a rush of song in the columns of the daily press."[10] Poets' corners in newspapers were filled with poems commemorating the disaster, the lessons to be drawn from it and specific incidents that happened during and after the sinking. Other poets published their own collections, as in the case of Edwin Drew, who rushed into print a collection called The Chief Incidents of the 'Titanic' Wreck, Treated in Verse ("may appeal to those who lost friends in this appalling catastrophe")[11] which he sent to President Taft and King George V; the copy now in the Library of Congress is the one that was sent to Taft.[12] Individual passengers were frequently memorialised and in several cases were held up as examples, such as in the example of the millionaire John Jacob Astor who was commended for the ostensibly heroic qualities of his death.[11] Charles Hanson Towne was typical of many in eulogising what Champ Clark called "the chivalric behaviour of the men on the ill-fated ship":[13]

But dream not, mighty Ocean, they are yours!

We have them still, those high and valiant men

Who died that others might reach ports of peace.

Not in your jealous depths their spirits roam,

But through the world to-day, and up to heaven![1]

The poets' output was of highly variable quality. Current Literature called some of it "unutterably horrible" and none of it "magically inspired", though its editors conceded that some "very creditable" poems had been written. The New York Times was harsher, describing most of the poems it received as "worthless" and "intolerably bad". A key sign of quality was whether it had been written on lined paper; if it had, it was likely to be among the worst category. The newspaper advised its readers "that to write about the Titanic a poem worth printing requires that the author should have something more than paper, pencil, and a strong feeling that the disaster was a terrible one."[10] John Sutherland and Stephen Fender nominate Christopher Thomas Nixon's lengthy poem The Passing of the Titanic (Sic transit gloria mundi) as "the worst poem to be inspired by the sinking of the Titanic":[14]

Through deep-sea gates of famed Southampton's bay,

A mammoth liner swings in churning slide

Her regal treat ridged opaline gulfs asway

And gauntlet flings to chance, wind, shoal and tide.

Ark wonderful! Palatial town marine,

Invention's flowe, rose-peak of skill-wrought plan;

The jewelled crown of Art the wizard, seen

Since Noah's trade in Shinar's land began.[1]

- ^ Sutherland & Fender 2011, p. 121.

Established poets also addressed the disaster with mixed results. Harriet Monroe wrote what Foster calls an "upbeat hackneyed Victorian hymn" to the American dead:

Your fathers, who at Shiloh bled,

Accept your company ...

Daughters of pioneers!

Heroes freeborn, who chose the best,

Not tears for you, but cheers![1]

- ^ Foster 1997, p. 27.

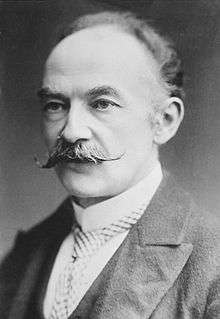

Thomas Hardy's The Convergence of the Twain (1912), his "Lines on the Loss of the Titanic", was a considerably more substantial work. His poem sets Titanic in a pessimistic post-Darwinian contrast between the achievements and arrogance of man and the humbling power of nature.[11] The building of Titanic in its unprecedented scale is contrasted with the origins of its nemesis, following a familiar nineteenth-century notion of the double or doppelganger (a theme most famously realised in Dr Jekyll and Mr. Hyde):[15]

And as the smart ship grew

In stature, grace and hue,

In shadowy silent distance grew the Iceberg too.

By the time the "twain" (two) converge, they have become "twin halves of one august event" which sends the Titanic to the bottom while the iceberg floats on. Now the ship lies at the bottom of the North Atlantic, and

Over the mirrors meant

To glass the opulent

The sea-worm crawls – grotesque, slimed, dumb, indifferent.

A number of other works of epic poetry were produced in later years. E. J. Pratt's authorship of The Titanic[16] (1935) reflected the great interest that the disaster had aroused in Canada, where many of the victims had been buried. The poem reflects a theme of tragic hubris, ending with the iceberg as the "master of the latitudes".[17] Pratt blames the ship's fate on the financiers responsible for commissioning it, whom he describes as "Grey-templed Caesars of the World's Exchange." After evoking the iceberg, "stratified ... to the consistency of flint," he gives a vivid disaster of the disaster in pentameter verse:

Climbing the ladders, gripping shroud and stay,

Storm-rail, ringbolt or fairlead, every place

That might befriend the clutch of hand or brace

Of foot, the fourteen hundred made their way

To the heights of the aft decks, crawling the inches

Around the docking bridges and cargo winches ...

As the ship sinks, Pratt describes the great noise heard by those aboard and in the lifeboats:[lower-alpha 1]

then following

The passage of the engines as they tore

From their foundations, taking everything

Clean through the bows from 'midships with a roar

Which drowned all cries upon the deck and shook

The watchers in the boats, the liner took

Her thousand fathoms journey to the grave.

The German poet Hans Magnus Enzensberger took a post-modernist approach in The Sinking of the Titanic (1978), a book-length epic poem. Whereas Pratt reflects the sinking of the Titanic as a definite historical event, Enzensberger simultaneously incorporates documentation – including original news wires from 15 April 1915 – while questioning the degree to which the event has become obscured by the accumulated myth-building of popular memory. As Foster puts it, in the poem "Titanic bears the weight of our belief and our disbelief, our desire for apocalypse and our fear of it, our fatigue, our talkative demise, the unbearable lightness of our being."[18]

The poem takes place within an autobiographical framework in which the poet becomes a character in his own poem and dies before the end, becoming merely one of a multitude of voices and perspectives. The iceberg appears as "an icy fingernail / scratching at the door and stopping short", but there is no real resolution, "no end to the end".[19] Enzensberger targets the endless commemorations by the Titanic memorabilia industry:

Relics, souvenirs for the disaster freaks,

food for collectors lurking at auctions

and sniffing out attics...

Something always remains –

bottles, planks, deck chairs, crutches,

debris left behind,

a vortex of words,

cantos, lies, relics –

breakage, all of it,

dancing and tumbling on the water.

Music

Songs

Numerous songs were produced in the immediate aftermath of the disaster. According to the American folklorist D.K. Wilgus, Titanic inspired "what seems to be the largest number of songs concerning any disaster, perhaps any event in American history."[20] In 1912–3 alone, over a hundred songs are known to have been produced in the US; the earliest known commercial song about Titanic was copyrighted just ten days after the disaster. Numerous pieces of sheet music and gramophone records were subsequently produced. In many cases they were not simply mere commercial exploitation of a tragedy (though that certainly did exist) but were a genuine and deeply felt popular response to an event that evoked many contemporary political, moral, social and religious themes. They drew a variety of lessons from the disaster, such as the levelling effect of the rich and poor, good and bad dying indiscriminately; the rich getting what they deserved; a lack of regard for God leading to the removal of divine protection; the heroism of the men who died; the role of human pride and hubris in causing the disaster.[20] The disaster inspired what D. Brian Anderson refers to as "countless forgettable hymns".[21] Many of the more secular songs celebrated the bravery of the men who had gone down with the ship, often highlighting their high social status and wealth and conflating it with their self-sacrifice and perceived moral worth.[22] A popular song of the time proclaimed:

There were millionaires from New York,

And some from London Town.

They were all brave, there were men and women to save

When the great Titanic went down.[1]

John Jacob Astor's death was highlighted as a particular example of noblesse oblige regarding his reputed refusal to leave the ship while there were still spaces in the lifeboats for women and children. The song A Hero Went Down with the Monarch of the Sea described Astor as "a handsome prince of wealth, / Who was noble, generous and brave" and ended: "Good-bye, my darling, don't you grieve for me, / I would give my life for ladies to flee." The Titanic Is Doomed and Sinking was even more laudatory:

There was John Jacob Astor,

What a brave man was he

When he tried to save all female sex,

The young and all, great and small,

Then got drowned in the sea.[1]

The self-sacrifice of captains of industry such as Astor was seen as all the more remarkable as it was made not just to aid their own womenfolk, but to help save those of much lower social status. As one Denver columnist put it, "the disease-bitten [immigrant] child, whose life at best is less than worthless, goes to safety with the rest of the steerage riff-raff, while the handler[s] of great affairs, ... whose energies have uplifted humanity, stand unprotestingly aside."[23]

The Titanic disaster became a popular theme for balladeers, blues, bluegrass and country singers in the Southern United States. Bluesman Ernest Stoneman scored one of his biggest hits with his song The Titanic in 1924, which was said to have sold over a million copies and became one of the best-selling songs of the 1920s.[24] The story of how his song was written illustrates the way the popular culture around Titanic cross-fertilised across different genres. According to Stoneman, he took the lyrics from a poem which he had seen in a newspaper. He "put a tune to it", most likely meaning that he adapted an existing tune with a suitable rhyme and meter. It subsequently emerged that the author of the poem was another country singer, Carson Robison, writing under the pseudonym "E. V. Body".[25] Other songs were written and performed by Rabbit Brown, Frank Hutchison, Blind Willie Johnson and the Dixon Brothers, who drew an explicit religious message from the sinking: "if you go on with your sins," you too will go "down with the old canoe."[26] In "Desolation Row," the final track of his 1965 album Highway 61 Revisited, Bob Dylan sings "praise be to Nero's Neptune, the Titanic sails at dawn"; the poets Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot are pictured as "fighting in the captain's tower," disregarded by spectators. Dylan would later write and record an entire song about the disaster for his 2012 album Tempest, interpolating images from the 1997 film within the song's narrative.

British songwriters commemorated the disaster with appeals to religious, chauvinistic and heroic sentiments. Songs were published with titles such as Stand to Your Post (Women and Children First!) and Be British (Dedicated to the Gallant Crew of the Titanic), the latter referring to the mythical last words of Captain Smith.[27] The Ship That Will Never Return by F. V. St Clair proclaimed: "The women and children the first for the boats –! And sailors knew how to obey,"[28] while "Be British" urged listeners to remember the plight of the survivors and donate to the charitable funds set up to assist them: "Show that you are willing! with a penny or a shilling! for those they've left behind."[29]

In African-American culture

The sinking of the Titanic had a particular resonance for African-Americans, who saw the ship as a symbol of the hubris of white racism and its sinking as retribution for the mistreatment of black people.[30] It was commemorated in a famous 1948 song by the blues singer Lead Belly, The Titanic (Fare thee, Titanic, Fare thee well). Popular legend had it that there were no black people aboard.[lower-alpha 2] Lead Belly's song portrays the black American boxing champion Jack Johnson attempting to board Titanic but being refused by Captain Smith, who tells him: "I ain't hauling no coal."[lower-alpha 3] Johnson remains on shore, bitterly bidding Titanic farewell, and dances the Eagle Rock as the ship goes under.[33]

The legend of the Titanic merged with that of a character in black folklore known as "Shine", a sort of trickster figure who was probably named after shoeshine. He was converted into a mythical black stoker aboard Titanic whose exploits were commemorated in "Toasts", long narrative poems performed in a dramatic and percussive fashion which were a forerunner of modern-day rapping.[34] He is portrayed as a central figure in the disaster, a person from "down below" who is the first to warn the captain about the water flooding in but is rebuked: "Go on back and start stackin' sacks, / we got nine pumps to keep the water back." He refuses, telling the captain: "Your shittin' is good and your shittin' is fine, / but there's one time you white folks ain't gonna shit on Shine."[35]

Shine is the only person aboard capable of swimming to safety and refuses, in revenge for the mistreatment of himself and his kin, to save the drowning white people. They offer him all manner of rewards, including "all the pussy eyes ever did see",[34] but to no avail; "Shine say, 'One thing about you white folks I couldn't understand: / you all wouldn't offer me that pussy when we was all on land."[36] He also receives marriage proposals from the wealthy women, in particular the captain's pregnant and unmarried daughter, but rejects them. In some versions another black man named Jim joins Shine in the water but is lost when he succumbs to the white people's allures and swims back to his death on the sinking ship. Shine swims all the way on to New York, outracing a whale or a shark along the way, although in some versions he goes off course and makes landfall in Los Angeles instead:[37]

He swimmed on till he came to New York town,

And people asked had the Titanic gone down.

Shine said "Hell yeah." They said, "How do you know?"

He said, "I left the big motherfucker sinkin' about thirty minutes ago."[1]

In the end he finds a drink and a woman to keep him company, and as one version puts it,

when all them white folks went to heaven

Shine was in Sugar Ray's bar drinking Seagram Seven.[1]

- ^ Foster 1997, p. 64.

The moral of the Toast is that neither the white man's money nor his women are worth the risk of acquiring them, therefore they should not be aspired to or coveted by black people. The unmarried pregnant captain's daughter is a sign that "even white nobility can transgress", as Paul Heyer puts it, and that white skin is not synonymous with purity. Also present in the Toast is the more general theme of a warning against overconfidence in the white man's technology.[38]

Concerts and musicals

Many composers also tackled the subject of the ship's sinking. Concerts were a major part of the fund-raising effort after the disaster; a super-orchestra of five hundred musicians played to a packed Royal Albert Hall under the direction of Sir Edward Elgar to raise money for the families of the musicians lost when Titanic sank. Other musical responses sought to evoke the disaster in musical form. Soon after the sinking a "Descriptive Musical Sketch (Piano, Chorus and Reciter)" was staged, and those wanting to re-enact the disaster at home could listen to the recording of The Wreck of the Titanic, a "Descriptive Piano Solo, right from the scene where the ship's bell rings for departure to the pathetic 'burial at sea' ... reminiscent of the sad disaster which will live in history as long as the world rolls on." There was even a Titanic Two-Step which was derived from a then-popular dance craze, though it is unclear how the dance steps were supposed to represent the sinking ship.[27]

Several musicals have been produced based on the story of the Titanic. Perhaps the best-known, as of its premiere in 1960, is The Unsinkable Molly Brown, dramatised and with music and lyrics by Meredith Willson, who had drawn his inspiration from Gene Fowler's 1949 book The Unsinkable Mrs. Brown. The Broadway musical presents a considerably embellished version of the real Margaret Brown's exploits; it portrays her taking command of a Titanic lifeboat and keeping the survivors in her charge going with bravado and her pistol. The writer Steven Biel notes that Molly Brown plays on American stereotypes of resilience and exceptionalism with a hint of isolationism.[27] It was made into a film of the same title in 1964, starring Debbie Reynolds.[39]

Another Titanic musical, called Titanic: A New Musical,[40] opened in April 1997 in New York to mixed reviews.[27] John Simon of New York magazine admitted approaching it "with a bit of a sinking feeling" and concluded that it was "an earnest but hopelessly mediocre show", which was not so much hit-and-miss as "almost all miss."[41] People magazine was much more complimentary, saying that it took "guts to write a musical about the century's most infamous disaster, yet Broadway's Titanic unflinchingly sails forth with its cargo of epic themes".[42] The lavish production incorporated a tilting stage to simulate the sinking.[39] It was a major box-office success; the musical won five Tony Awards and played on Broadway for two years, with performances also held in Germany, Japan, Canada and Australia.[42]

Plays, dance and multimedia works

Various plays have featured the disaster either as their principal subject or in passing. One of the earliest directly addressing the sinking of the Titanic (albeit in a thinly disguised form) was The Berg: A Play (1929) by Ernest Raymond that is said to have been the basis of the film Atlantic. Noël Coward's highly successful 1931 play Cavalcade, adapted into an Oscar-winning film of the same name in 1933, has a romantic plot which features a shock ending set aboard the Titanic.[43]

In 1974 the disaster was used as the backdrop for the play Titanic, which D. Brian Anderson characterises as "a one-act sexual farce". The passengers and crew eagerly await the arrival of the iceberg but the ship fails to find it. While Titanic wanders the ocean looking for the iceberg, those aboard fill the time by making a series of sexual revelations, such as the disclosure by one girl that she "used to enjoy keeping a mammal in her vagina." When the collision does eventually come, it turns out to be a practical joke by the captain's wife. The off-Broadway production, whose cast included a young Sigourney Weaver, received what Anderson describes as "howling reviews".[44]

Jeffrey Hatcher's 1992 play Scotland Road (the title refers to a passageway on Titanic) is a psychological mystery which opens with the discovery of a dehydrated woman found on an iceberg in the North Atlantic in 1992. She wears 1912-style clothing but can only say the word "Titanic". The great-grandson of John Jacob Astor investigates whether the woman is a genuine survivor from 1912, somehow projected forward through time, or is part of some bizarre hoax.[45] More recently the British playwrights Stewart Love and Michael Fieldhouse have written plays (Titanic (1997) and The Song of the Hammers (2002) respectively) that address the often-neglected aspect of the views and experiences of the men who built the Titanic.[46]

There have also been a number of dance and multimedia productions. The Canadian choreographer Cornelius Fischer-Credo devised a dance work called The Titanic Days which, in turn, was adapted for the title track of an album by the singer Kirsty MacColl. The Belgian dance company Plan K performed a work called Titanic at the 1994 Belfast Festival in which a flotilla of refrigerators – in real life part of the cargo aboard Titanic – stands in for the drifting mass of ice that ultimately destroys the ship.

The British composer Gavin Bryars created a multimedia work called The Sinking of the Titanic (1969), based on the conceit that "sounds never completely die but merely grow fainter and fainter. What if the music of the Titanic's band might still be playing 2,500 fathoms under the sea?"[47] The piece uses a collage of sounds, ranging from underwater recordings to reminiscences of survivors and morse code messages, to evoke the sounds of the Titanic. As Foster puts it,

We hear a muffled voice, like a drowned survivor giving testimony from beneath the waves, as it were, and the swaying music of the water, and at the section's end the ominous drips as of water that magnify into depth-soundings, the voice now silent or merged into ocean, abyss, the underwater echoes of our fate.[48]

The work was first issued on record in 1975, as the first release on Brian Eno's short-lived label Obscure Records (paired with Bryars' composition Jesus' Blood Never Failed Me Yet).

Slideshows and newsreels

Within days of Titanic's sinking, newsreels and even slide shows were playing in crowded cinemas and theatres in the United States and Europe. By the end of April 1912, no fewer than nine American companies had issued sets of Titanic slides that could be bought or rented for public showings, accompanied by posters, lobby photos, lecture scripts and sheet music.[49] They were intended to be shown as part of a mixed programme combining magic lantern slides with short dramatic, comic and scenic films.[50] Charles A. Pryor of New York's Pryor and Clare was among the first photographers to make it aboard the Carpathia on her return from the scene of the sinking and took many pictures of Captain Rostron, the Titanic's survivors and Carpathia's crew. His subsequent advertising, published in the New York Clipper, emphasised the likely level of popular interest:

MR THEATRE MANAGERPack your Theatre with the BIGGEST SENSATION OF THE AGE

"The Great Titanic Disaster"

Mr. Chas. A. Pryor ... chartered a tug boat, and has the real genuine money getter ... [the pictures] are GREAT, showing all notable persons connected with the tragedy, the lifeboats, the life preservers, and have the last bill of fare that was served on the Titanic.[51]

Slide shows made less of an impact on British audiences, who seem to have preferred a more "artistic" approach. One of the most elaborate visual responses to the disaster was a "Myriorama" (a neologism meaning "many scenes") titled The Loss of the Titanic performed by Charles William and John R. Poole, whose family had been staging such shows since the 1840s. It involved the use of a series of scenes painted on fine gauze sheets, manipulated in such a way that they would appear to dissolve from one scene to the next while music was played and a dramatic and emotive recital was performed in the foreground. According to the publicity material for the Titanic Myriorama, it featured "the spectacle staged in its entirety by John R. Poole, and every endeavour made to convey a true pictorial idea of the whole history of the disaster ... Unique Mechanical and Electric Effects, special music and the story described in a thrilling manner."[52] The "Immortal Tale of Simple Heroism" was performed through eight tableaux, starting with "A splendid marine effect of the Gigantic Vessel gliding from the Quayside at Southampton" and ending with praise for "the simple courage which remains for ever a proud heritage of the Anglo-Saxon race." According to contemporary reports, the show "often reduced audiences to tears."[53]

Newsreels on the Titanic disaster were hampered by the fact that hardly any footage of the ship existed. A few seconds of film of Titanic's launching on 31 May 1911 were shot in Belfast by local company Films Limited,[54] and the Topical Budget Company appears to have had some footage – now lost – of the ship at Southampton.[55] Other than that, all that existed were photographs, which were of only limited use in a motion picture. Newsreel strands, such as the Gaumont Film Company's Animated Weekly, made up for the lack of footage of the ship itself by splicing in newly shot material of the aftermath of the sinking. These included scenes such as Carpathia arriving at New York, the Titanic survivors disembarking and the crowds gathering outside the White Star Line offices in Brooklyn as lists of the casualties were being posted.[56]

Gaumont's Titanic newsreel was hugely successful and played to packed houses around the world.[57] The first Titanic newsreels appeared in Australia as early as 27 April, while in Germany the Martin Dentler company promised that its Titanic newsreel would "guarantee a full house!". In many places, patrons were handed copies of "Nearer, My God, To Thee" to sing at the close of the film (according to German cinema owner Fred Berger, "much lusty singing took place at [the] screening") while in Britain a family of entertainers used their Gavioli organ to provide the Gaumont newsreel with an accompaniment of nautical tunes.[58] Even though Gaumont was a French company, its Titanic did comparatively poorly in its home country; this was perhaps due to the local news being dominated not by Titanic but by the simultaneous capture of the Bonnot Gang of anarchist bandits.[59]

Some movie companies tried to make up for the lack of footage by passing off film of other liners as being of the Titanic, or marketing the footage of Titanic's launch as showing her sinking. The proprietor of one cinema on New York's 34th Street was beaten up several times by angry customers who fell victim to one such scam. The Dramatic Mirror reported that "both eyes had been blacked and several teeth have been lost, and a blue-black bruise ... now covers almost the entire southern aspect of his face." He was defiant all the same: "Even after I pay the doctor and the dentist I'll clear five hundred dollars. And there isn't an untruthful word in those advertisements. There ain't nobody can say I ain't a gent."[60] In Bayonne, New Jersey, a cinema was the scene of a riot on 26 April 1912 after it falsely advertised a film showing "the sinking of the Titanic and the rescue of her survivors." The New York Evening World reported the following day that the local police had to intervene after "the audience having been led to believe they were to see something sensational, uttered loud protests. Seats were torn loose in one theatre."[61] In the end, the local police chief banned the performance. Similar public outrage and disorder resulting from a proliferation of fake Titanic disaster reels prompted the mayor of Memphis, Tennessee to ban "any moving picture reels portraying the Titanic disaster or any phase thereof".[60] The mayors of Philadelphia and Boston soon followed suit.[62] However, the Titanic newsreel bubble soon burst, and by August 1912 trade newspapers were reporting that compilations of stock footage of Titanic intercut with pictures of icebergs "don't attract audiences any more."[63]

Drama films

There have so far been eight English-language drama films (not counting TV movies) about the Titanic disaster: four American, two British and two German, produced between 1912 and 1997.

1912–43

The first drama film about the disaster, Saved from the Titanic, was released only 29 days after the disaster. Its star and co-writer, Dorothy Gibson, had actually been on the ship and was aboard Titanic's No. 7 lifeboat, the first to leave the ship.[64] The film presents a heavily fictionalised version of Gibson's experiences, told in flashback, intercut with newsreel footage of Titanic and a mockup of the collision itself.[65] Released in the United States on 14 May 1912[66] and subsequently shown internationally, it was a major success.[67] However, it is now considered a lost film, as the only known prints were destroyed in a fire in March 1914.[68]

Gibson's film competed against the German film In Nacht und Eis (In Night and Ice), directed by the Romanian Mime Misu, who played the Titanic's Captain Smith. It was largely shot aboard the liner SS Kaiserin Auguste Victoria. The fatal collision was depicted by ramming a 20-foot (6.1 m) model of Titanic into a block of floating ice. The impact knocks the passengers off their feet and causes pandemonium on board. The film does not depict the evacuation of the ship but shows the captain panicking while water rises around the feet of wireless operator Jack Phillips as he sends SOS messages. The ship's band is repeatedly shown playing musical pieces, the titles of which are shown on captions; it appears that a live band would play the corresponding music to the cinema audience. As the film ends, the waves close over the swimming captain.[63]

Although not strictly about Titanic, a number of other drama films were produced around this time that may have been inspired by the disaster. In October 1912 the Danish film company Nordisk released Et Drama på Havet (A Drama at Sea) in which a ship at sea catches fire and sinks, while passengers fight to board lifeboats. It was released in the United States as The Great Ocean Disaster or Peril of Fire. The same company produced a follow-up film in December 1913, which was also released in the US. Titled Atlantis, it was based on a novel of the same name by Gerhart Hauptmann and culminated with a depiction of a sinking liner. It was the longest and most ambitious Danish film to date, taking up eight reels and costing a then-huge sum of $60,000.[69] It was filmed aboard a real liner, the SS C.F. Tietgen, chartered especially for the filming with 500 people aboard. The sinking scene was filmed in the North Sea.[70] The Tietgen sank for real five years later when she was torpedoed by a German U-boat. A British film company planned to go one better by building and sinking a replica liner, and in 1914 the real-life scuppering of a large vessel took place for the Vitagraph picture Lost in Mid-Ocean.[71]

The 1929 British sound film Atlantic was clearly (though loosely) based on the story of the Titanic. Derived from Ernest Raymond's play The Berg, it focuses on the sinking of a liner carrying a priest and an atheist author, both of whom must come to terms with their imminent deaths. Exterior scenes were shot on a ship moored on the River Thames but most of the film is set in an interior lounge, in a very static and talkative fashion. The ship's evacuation is depicted as taking place amid pandemonium but the actual sinking is not shown; although the director did shoot sinking scenes, it was decided that they should not be used.[72]

The Hollywood producer David O. Selznick tried to persuade Alfred Hitchcock to make a Titanic film for him in 1938, based on a novel of the same name by Wilson Mizner and Carl Harbaugh. The storyline involves a gangster who renounces his life of crime when he falls in love with a woman aboard Titanic. Selznick envisaged buying the redundant liner Leviathan to use as a set. Hitchcock disliked the idea and openly mocked it; he suggested that a good way to shoot it would be to "begin with a close-up of a rivet while the credits rolled, then to pan slowly back until after two hours the whole ship would fill the screen and The End would appear." When asked about the project by a reporter he said, "Oh yes, I've had experience with icebergs. Don't forget I directed Madeleine Carroll" (who, as Hitchcock was probably aware, had starred in the Titanic-inspired Atlantic).[73] To add to the problems, Howard Hughes and a French company threatened lawsuits as they had their own Titanic scripts, and British censors let it be known that they disapproved of a film that might be seen as critical of the British shipping industry.[74] The project was eventually abandoned as the Second World War loomed and Hitchcock instead made Rebecca for Selznick in 1940, winning an Oscar for Best Picture.[73]

The Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels personally commissioned Titanic, a 1943 propaganda film made during World War II. It was largely shot in Berlin with some scenes filmed aboard the SS Cap Arcona. It focuses on a fictitious conflict between "Sir" Bruce Ismay and John Jacob Astor, reimagined as an English Lord, for control of the White Star Line. An equally fictitious young German First Officer, Petersen, warns against Ismay's reckless pursuit of the Blue Riband, calling Titanic a ship "run not by sailors, but by stock speculators". His warnings fall on deaf ears and the ship hits an iceberg. Several aspects of the plot are reflected in James Cameron's 1997 Titanic: a girl rejects her parents' wishes to pursue the man she loves, there is a wild dancing scene in steerage and a man imprisoned in the ship's flooding prison is freed with the help of an emergency ax. Herbert Selpin, the film's director, was removed from the project after making unflattering remarks about the German war effort. He was personally questioned by Goebbels and 24 hours later he was found hanged in his cell. The film itself was withdrawn from circulation shortly after release on the grounds that a film portraying chaos and mass death was injurious to war morale, though it has also been suggested that its theme of a morally upright hero standing up to a reckless leader steering the vessel to disaster was too politically sensitive for the Nazis to tolerate.[75] It was also too sensitive for the British, who prevented it from being shown in the western zones of occupied Germany until the 1960s. East Germans had no such difficulty as the film accorded well with the anti-capitalist sentiments of their communist rulers.[76]

1953–2012

Barbara Stanwyck and Clifton Webb starred as an estranged couple in the 1953 film Titanic. The film makes little effort to be historically accurate and focuses on the human drama as the couple, Mr and Mrs Sturges, feud over the custody of their children while their daughter has a shipboard romance with a student travelling on the ship. As Titanic sinks the couple are reconciled, the women are rescued and Sturges and his son go down with the ship. The film earned an Oscar for its screenplay.[77] The film's lack of regard for historical accuracy can be explained by the fact that it uses the disaster merely as a backdrop for the melodrama. This proved unsatisfactory for some, notably Belfast-born William MacQuitty, who had witnessed the launch of Titanic as a boy and had long wished to make a film that put the nautical events front and centre.[78]

A Night to Remember, starring Kenneth More, was the outcome of MacQuitty's interest in the Titanic story. Released in 1958 and produced by MacQuitty, the film is based on the 1955 book of the same name by Walter Lord.[79] Its budget of £600,000 (£11,868,805 today) was exceptionally large for a British film[80] and made it the most expensive film ever made in Britain up to that time. The film focuses on the story of the sinking, portraying the major incidents and players in a documentary-style fashion with considerable attention to detail;[79] 30 sets were constructed using the builders' original plans for Titanic.[39] The ship's former Fourth Officer Joseph Boxhall and survivor Lawrence Beesley acted as consultants.[79] One day during shooting Beesley infiltrated the set but was discovered by the director, who ordered him off; thus, as Julian Barnes puts it, "for the second time in his life, Beesley left the Titanic just before it was due to go down."[81]

Although it won numerous awards including a Golden Globe Award for Best English-Language Foreign Film and received high praise from reviewers on both sides of the Atlantic,[82] it was at best only a modest commercial success due to its original huge budget and a relatively poor impact in America.[83] It has nonetheless aged well; the film has considerable artistic merit and, according to Professor Paul Heyer, it helped to spark the wave of disaster films that included The Poseidon Adventure (1972) and The Towering Inferno (1974).[82] Heyer comments that it "still stands as the definitive cinematic telling of the story and the prototype and finest example of the disaster-film genre."[84]

In 1979 EMI Television produced S.O.S. Titanic, a TV movie that tells the story of the disaster as a personal drama. Survivor Lawrence Beesley (played by David Warner) is presented as a romantic hero and Thomas Andrews (played by Geoffrey Whitehead) is also seen as a significant character for the first time. Ian Holm's J. Bruce Ismay is presented as the villain.[85] Warner went on to play Caledon Hockley's manservant, Spicer Lovejoy, in James Cameron's Titanic in 1997.[86] The production was partially filmed aboard a real liner, the RMS Queen Mary.[87]

1980's Raise the Titanic was an expensive flop. Based on the best-selling book of the same name by thriller writer Clive Cussler, the plot involves Cussler's hero Dirk Pitt (Richard Jordan) seeking to salvage an intact Titanic from her location on the sea bed. He aims to gain a decisive American advantage in the Cold War by retrieving a stockpile of a fictitious ultra-rare mineral of military value, "byzanium", that the ship was supposedly carrying on her maiden voyage.[88] The film, directed by Jerry Jameson, cost at least $40 million. It was the most expensive movie made up to that time but made only $10 million at the box office. Lew Grade, the producer, later remarked that it would have been "cheaper to lower the Atlantic".[89]

James Cameron's Titanic is the most commercially successful film about the ship's sinking. Titanic became the highest-grossing film in history nine weeks after opening on 19 December 1997, and a week later became the first film ever to gross $1 billion worldwide. By March 1998 it had made over $1.2 billion,[90] a record that stood until Cameron's next drama film Avatar overtook it in 2009.[91] Cameron's film centres around a love affair between First Class passenger Rose DeWitt Bukater (Kate Winslet) and Third Class passenger Jack Dawson (Leonardo DiCaprio).[92] Cameron designed the characters of Rose and Jack to serve as what he has termed "an emotional lightning rod for the audience", making the tragedy of the disaster more immediate. As Peter Kramer puts it, the love story is intended to humanise the disaster, while the disaster lends the love story a mythic aspect.[93] Cameron's film cost $200 million, making it the most expensive film ever made up to that time;[94] much of it was shot on a vast, nearly full-scale replica of Titanic's starboard side built in Baja California, Mexico.[95] The film was converted into 3D and re-released on 4 April 2012 to coincide with the centenary of the sinking.[96][97] Cameron's film is the only Titanic drama to have been partially filmed aboard the vessel, which the Canadian director visited in two Russian submersibles in the summer of 1995.[98]

Television

- See the list of television movies and episodes for examples of the many references to the Titanic and her disaster.

With the advent of television, the themes and social microcosm provided by the Titanic scenario inspired TV productions, from expansive serial epics to satirical animated spoofs. The list of genres relating to the Titanic grew to include science fiction; and beginning with the first episode of The Time Tunnel in 1966, the RMS Titanic has become an irresistible destination for time-travelers.

The Titanic was also spoofed in the Pokémon series as the S.S. Cussler in the episode An Undersea Place to Call Home!.. After it sunk, it became the home of many oceanic Pokémon, most notably Dragalge who constructed the wreck along with other shipwrecks into a wildlife community.

Books

Survivors' accounts and "instant books"

The sinking of the Titanic has been the inspiration for a huge number of books in the century since April 1912; as Steven Biel puts it, "Rumor has it that the three most written-about subjects of all time are Jesus, the [American] Civil War, and the Titanic disaster."[99]

The first wave of books was published shortly after the sinking. Two survivors published their own accounts at the time: Lawrence Beesley's The Loss of the S.S. Titanic, and Archibald Gracie's The Truth about the Titanic. Beesley started writing his book shortly after being rescued by the RMS Carpathia and supplemented it with interviews with fellow-survivors. It was published by Houghton Mifflin within only three weeks of the disaster. Gracie carried out extensive research and interviews, as well as attending the US Senate inquiry into the sinking. He died in December 1912, just before his book was published.[100]

Titanic's former Second Officer, Charles Lightoller, published an account of the sinking in his 1935 book Titanic and Other Ships, which Eugene L. Rasor characterises as an apologia.[101] Stewardess Violet Jessop gave a fairly short first-hand account in her posthumously published Titanic Survivor (1997).[102] Carpathia's 1912 captain, Arthur Rostron, published an account of his own role in his 1931 autobiography Home from the Sea.[103]

Various other authors of the first wave published compilations of news reportage, interviews and survivors' accounts. However, as W. B. Bartlett comments, they were "marked by some journalism of highly suspect and sensationalist variety ... which tell[s] more about the standards of journalistic editorialism at the time than they do about what really happened on the Titanic."[104] The British writer Filson Young's book Titanic, described by Richard Howells as "darkly rhetorical ... [and] heavily laden with cultural pronouncement", was one of the first to be published, barely a month after the disaster.[105] Many of the American books followed an established form that had been used after other disasters such as the Galveston Storm of 1900 and the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake. Publishers rushed out "instant" or "dollar books" which were published in great numbers on cheap paper and sold for a dollar by door-to-door salesmen. They followed a fairly similar style, which D. Bruce Anderson describes as "liberal use of short chapters, telegraphic subheadings, and sentimental, breezy prose". They summarised press coverage supplemented by extracts from survivors' accounts and sentimental eulogies of the victims.[106] Logan Marshall's The Sinking of the Titanic and Great Sea Disasters (also published as On Board the Titanic: The Complete Story With Eyewitness Accounts) was a typical example of the genre.[104] Many such "dollar books", such as Marshall Everett's Story of the Wreck of the Titanic, the Ocean's Greatest Disaster: 1912 Memorial Edition, were styled as "memorial" or "official" editions in a bid to grant them a bogus degree of extra authenticity.[107]

A Night to Remember and after

The "second wave" of Titanic–related books was launched in 1955 by Walter Lord, a New York advertising executive with a lifelong interest in the story of the Titanic disaster. Writing in his spare time, he interviewed around sixty survivors as well as drawing on previous writings and research.[108] His book A Night to Remember was a huge success, selling 60,000 copies within two months of its publication. It remained listed as a best-seller for six months.[109] The book has never been out of print, reached its fiftieth edition by 1998, and has been translated into over a dozen languages.[109][110] It was adapted twice for the screen, first as a live TV drama broadcast by NBC in March 1956[110] and subsequently as the classic British film A Night to Remember starring Kenneth More.[84]

Lord's book was followed by The Maiden Voyage (1968) by the British naval historian Geoffrey Marcus, which told the entire story of the disaster from the passengers' departure to the subsequent public inquiries. He blamed Captain Smith and the White Star Line for the failings that led to the disaster and castigated what he called the "official lie" and "planned official prevarication" of the British inquiry. It was well-received, with Lord himself describing it as "penetrating and all-inclusive."

In 1986 Walter Lord wrote a sequel to his A Night to Remember titled The Night Lives On, in which he expressed second thoughts about some of what he wrote in his previous work. As Michael Sragow, writer and editor for The Baltimore Sun, noted: "[Lord] wondered whether Lightoller had carried the chivalrous rule of women and children first too far, to women and children only."[111]

Post-discovery books

The discovery of the wreck of the Titanic in 1985 spurred a fresh wave of books, with even more published after 1997 and in 2012 to capitalise on the success of James Cameron's film Titanic and the centenary of the disaster respectively. Robert Ballard told the story of his search and discovery of the ship in his 1987 book The Discovery of the Titanic, which became a best-seller;[112] Rasor describes it as "the best and most impressive" of the accounts of the search.[113] John P. Eaton and Charles A. Haas produced Titanic: Triumph and Tragedy: A Chronicle in Words and Pictures in 1986, a 320-page illustrated volume telling the story of Titanic in great detail from design and fitting-out, through to the maiden voyage, the disaster and the aftermath. The book takes a heavily visual approach with many contemporary photographs and pictures, and is described by Anderson as "encyclopedic [and] comprehensive" and "the consummate Titanic guide."[114]

Wyn Wade's 1992 book "The Titanic: Disaster of a Century"[115] attempts to re-tell the story of the ship from financing and construction all the way through to the rescuing of survivors by the RMS Carpathia. Then it takes the reader into the investigation of the disaster by the United States Senate, led by Michigan Senator William Alden Smith. The book concludes with a look at resulting legislation and its legacy in society. In trying to draw lessons from these events, Wade writes, "Titanic was the incarnation of man’s arrogance in equating size with security; his pride in intellectual (divorced from spiritual) mastery; his blindness to the consequences of wasteful extravagance; and his superstitious faith in materialism and technology. What is alarming is how much these pitfalls still typify the Western – especially the English-speaking – world of today in our continuing Age of Anxiety. As long as this self-same Hubris is with us, Titanic will continue to be not just a haunting memory of the recurrent past, but a portent of things to come – a Western apocalypse, perhaps, wherein the world, as Western man has known and shaped it, is undermined from within, not overcome from without; and ends not in holocaust but with a quiet slip into oblivion.”

Don Lynch's Inside the Titanic (1997) presents an overview of the ship and the disaster, illustrated by the artist Ken Marschall, whose pictures of Titanic and other lost ships have become famous.[116] Susan Wels' book Titanic: Legacy of the World's Greatest Ocean Liner (1997) documents the salvage work of RMS Titanic Inc, while Daniel Allen Butler provides a scholarly examination of the Titanic story in his 1998 book Unsinkable: The Full Story of the RMS Titanic. Robin Gardiner's 1995 and 1998 books Riddle of the Titanic and Titanic: The Ship that Never Sank, put forward a conspiracy theory that the wreck is actually that of the RMS Olympic, which supposedly the White Star Line had secretly switched with Titanic as part of an insurance scam.[117]

Novels

A variety of novels set aboard the Titanic has been produced over the years. One of the earliest was the German author Robert Prechtl's Titanic, first published in Germany in 1937 and subsequently in Britain in 1938 and in the US in 1940 (translated into English). The main protagonist and hero of the novel is John Jacob Astor; the book focuses on the theme of redemption, though it takes a markedly anti-British stance.[118] It is considered the first serious Titanic novel.[119]

One of the most famous novels associated with the disaster is a book written by Morgan Robertson fourteen years prior to the Titanic's maiden voyage, Futility, or the Wreck of the Titan. Published in 1898, the book is noted for its similarities with the actual sinking. It tells the story of a huge ocean liner, the Titan, which sinks in the North Atlantic on her maiden voyage after colliding with an iceberg. The Titan is depicted as only slightly larger than Titanic, both ships have three propellers and carry 3,000 passengers, both have watertight compartments, both are described as "unsinkable" and both have too few lifeboats "as required by law". The collision is described within the novel's first twenty pages; the rest of the book deals with the aftermath. The similarities between art and life were recognised immediately in 1912 and the book was republished soon after the sinking of Titanic, with several editions being published since then.[120]

Thriller author Clive Cussler wrote the successful Raise the Titanic! in 1976, which was made into a hugely expensive flop of a movie four years later.[121] The same theme was reflected in The Ghost from the Grand Banks (1990) by Arthur C. Clarke, which tells the story of two competing expeditions seeking to raise each half of the wreck of the Titanic and tow them to Tokyo in time for the centenary of the sinking in 2012.[122][118] An earlier Clarke novel Imperial Earth, (1976, but set in the late 23rd century AD) mentions that the Titanic has been raised and is now a museum exhibit in New York City.

The ship becomes the backdrop for a romance in Danielle Steel's 1991 novel No Greater Love, in which a young woman becomes the sole caregiver for her siblings after her parents die aboard Titanic.[123] In 1996 NBC adapted it into a TV movie of the same name, which Anderson characterises as "rather sterile and perfunctory."[124]

Voyage on the Great Titanic: The Diary of Margaret Ann Brady, RMS Titanic, 1912 by Ellen Emerson White is a fictional diary of a girl travelling on the Titanic - part of the Dear America series, in which each book is a fictional diary set at a significant point in American history.

Various authors have also used Titanic as the setting for murder mysteries, as in the case of Max Allan Collins' 1999 novel The Titanic Murders, part of his "disaster series" of murder mysteries set amidst famous disasters. The writer Jacques Futrelle, who perished in the disaster, takes the role of amateur detective in solving a murder aboard Titanic shortly before her fatal collision.[118][121]

In 1996 Beryl Bainbridge published Every Man for Himself, which won the Whitbread Award for Best Novel that year as well as being nominated for the Booker Prize and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. The title comes from some of the reputed last words of Titanic's Captain Smith and features a fictional nephew of J. P. Morgan, the ultimate owner of the ship, who seeks to befriend and seduce the rich and famous aboard the ship. He accompanies Thomas Andrews as the ship sinks and makes his escape aboard a capsized lifeboat (like Sherlock Holmes). The book incorporates a number of myths and conspiracy theories about Titanic, notably Robin Gardiner's claim that she was switched for her sister ship Olympic.[125][126]

Douglas Adams' Starship Titanic (1997), written by ex-Python Terry Jones from an outline by Douglas Adams, tells the story of a doomed starship launched before she was finished. The ship's architect, Leovinus, undertakes an investigation to find out why the ship underwent a Spontaneous Massive Existence Failure shortly after launch. A computer game based on the book was released in 1998.[127]

Connie Willis's Passage (2001) is a story about a researcher who takes part in an experiment to simulate near-death experiences. During these experiences, instead of the classic images of angels, the researcher finds herself on the Titanic. The book details her efforts to understand the meaning of her visions and with history of the ship and its sinking.

In TimeRiders (2010) by Alex Scarrow, Liam O'Conner, a fictional steward on the Titanic, is rescued during the sinking by a man named Foster, who brings him forwards in time to September 11, 2001 in order to recruit him into an entity known as 'The Agency' which was set up to prevent destructive time travel.

In James Morrow's short story The Raft of the Titanic, only nineteen people died in the sinking; the rest are saved.

In The Company of the Dead by David J. Kowalski, an alternate timeline is created when an accidental time-traveler tries to prevent the sinking of the Titanic after he is sent back to 1911, only for his actions to see it destroyed merely a few hours later in what appears to be a more deliberate attack than the clear accident of the original timeline. The subsequent changes to history result in a world where America split in two after a new civil war, Germany has ruled Europe since what was the First World War in our timeline, and the world is being pushed to disaster as society has advanced too fast without the disaster of the Titanic to encourage people to consider the care needed for technological progress.

Video games

Since the discovery of the wreck, several video games have been released with a RMS Titanic theme for various platforms; most of these are either about the player being a passenger on the doomed ship trying to escape, or a diver exploring and possibly trying to raise the wreck.[128] One game, Titanic: Adventure Out of Time, was released in 1996 by Cyberflix, one year prior to James Cameron's film.

In the 1999 video game Duke Nukem: Zero Hour the level Going Down features the Titanic.

In the 2010 video game Nine Hours, Nine Persons, Nine Doors, the main characters were all put onto a sinking ship by a mysterious person named Zero. In their introduction, Zero references the Titanic's sinking in the line "On April 14, 1912... the famous ocean liner Titanic crashed into an iceberg. After remaining afloat for 2 hours and 40 minutes, it sank beneath the waters of the North Atlantic. I will give you more time. 9 hours is the amount of time you will be given to escape." It is later discovered that the "ship" they are on is a replica of one of Titanic's sister ships, the Gigantic. In real life, Gigantic was rumored to have been the original name of the HMHS Britannic, which was indeed one of the Titanic's sister ships.

In the 2013 video game BattleBlock Theater a ship with two funnels bearing the name Titanic is briefly seen during a cutscene.

Since 2012, a video game titled Titanic: Honor and Glory has been in development by Four Funnels Entertainment. According to the developers, the game will feature a fully interactive recreation of the ship and the port of Southampton, and will include a tour mode of the ship in port, and a story mode told mostly in real time.[129]

Visual Media

American artist Ken Marschall has painted Titanic extensively - depictions of the ship's interior and exterior, its voyage, its destruction and its wreckage. His work has illustrated numerous written works about the disaster including books and magazine stories and covers and he was a consultant on James Cameron's successful Titanic film. [130]

Memorabilia

The disaster prompted the production of all kinds of collectibles and memorabilia, many of which had overtly religious overtones. Collectible postcards were in great demand in Edwardian England; in an era when domestic telephones were rare, sending a short message on a postcard was the early 20th century equivalent of a text message or a tweet.[131] A few postcards were published before the disaster showing Titanic under construction or newly completed and became objects of great demand afterwards.[132] Even more desirable to collectors were the small number of postcards that had been written aboard Titanic during her maiden voyage and posted while she was in the harbours at Cherbourg and Queenstown.[133]

After the sinking, memorial postcards were issued in huge numbers to serve as relics of the disaster. They were often derived from nineteenth-century religious art, showing grieving maidens in stylised poses alongside uplifting religious slogans.[133] For many devout Christians the disaster had disturbing religious implications; the Bishop of Winchester characterised it as a "monument and warning to human presumption", while others saw it as divine retribution: God putting Man in his place, as had happened to Noah. The final location of Titanic, in the abyss 12,000 feet (3,700 m) down, was interpreted as a metaphor for hell and purgatory, the Christian Abyss.[134] One particular aspect of the sinking became iconic as a symbol of piety – the reputed playing by the ship's band of the hymn Nearer, My God, To Thee as she went down. The same hymn and slogan was repeated on many items of memorabilia issued to memorialise the disaster.[135] Bamforth & Company issued a hugely popular postcard series in England, showing verses from the hymn alongside a mourning woman and Titanic sinking in the background.[136]

There was only a limited number of surviving photographs of Titanic, so some unscrupulous postcard publishers resorted to outright fakery to satisfy public demand. Photographs of her sister ship Olympic were passed off as being Titanic. A common mistake made in fake photographs was that of showing the ship's fourth funnel billowing smoke; in fact, the funnel was a dummy, added for purely aesthetic purposes. Photographs of the Cunard Line vessels Mauretania and Lusitania were retouched and passed off as the Titanic, or even as the Carpathia, the vessel which rescued the Titanic survivors.[137] Other postcards celebrated the bravery of the male passengers, the crew and especially the ship's musicians.[132]

A great variety of other collectible items was produced, ranging from tin candy boxes to commemorative plates, whiskey jiggers,[138] and even teddy bears. One of the most unusual items of Titanic memorabilia was the 655 black teddy bears produced by the German manufacturer Steiff. In 1907 the company produced a prototype black teddy bear that was not a commercial success. Buyers disliked the gloomy appearance of the black-furred bear. After the Titanic disaster the company produced a limited run of 494 black "mourning bears" which were displayed in London shop windows. They rapidly sold out, and a further 161 were produced between 1917 and 1919. They are today among the most sought-after of all teddy bears.[139] One pristine example was sold in December 2000 at Christie's of London after emerging from a cupboard where its owner, who disliked the bear's appearance, had kept it for 90 years. It sold for over £91,000 ($136,000), far more than had been expected.[140][141]

Notes

- ↑ At the time this was attributed to the ship's machinery coming loose, but it now seems more likely to have been the sound of the hull coming apart as Titanic broke up.

- ↑ In fact there was one – Joseph Laroche, a Haitian who had married a white Frenchwoman and travelled second-class with his two small daughters. He perished in the disaster, but his wife and children survived.[31]

- ↑ In reality Johnson visited England in 1911, not 1912, and returned safely to the US aboard the RMS Celtic, not the Titanic.[32]

References

- 1 2 Anderson 2005, p. 1.

- ↑ Foster 1997, pp. 22–23.

- 1 2 3 Foster 1997, p. 23.

- ↑ Taylor 2011, p. 28.

- ↑ Foster 1997, pp. 12–13.

- ↑ Foster 1997, p. 36.

- ↑ Barczewski 2011, p. xiv.

- ↑ Biel 1998, p. 12.

- ↑ Biel 1998, pp. 12–13.

- 1 2 Biel 1996, p. 31.

- 1 2 3 Foster 1997, p. 27.

- ↑ Anderson 2005, p. 155.

- ↑ Biel 1996, p. 25.

- ↑ Sutherland & Fender 2011, p. 121.

- ↑ Foster 1997, p. 28.

- ↑ Pratt 1935.

- ↑ Foster 1997, p. 30.

- ↑ Foster 1997, p. 32.

- ↑ Foster 1997, p. 31.

- 1 2 Foster 1997, p. 33.

- ↑ Anderson 2005, p. 159.

- ↑ Biel 1996, p. 42.

- ↑ Biel 1996, p. 43.

- ↑ Ward 2012, p. 233.

- ↑ Tribe 1993, pp. 40–41.

- ↑ Ward 2012, pp. 233–34.

- 1 2 3 4 Foster 1997, p. 34.

- ↑ Howells 2012, p. 124.

- ↑ Howells 2012, p. 119.

- ↑ Foster 1997, p. 63.

- ↑ Hughes June 2000.

- ↑ Ward 2012, p. 235.

- ↑ Foster 1997, pp. 63–64.

- 1 2 Foster 1997, p. 64.

- ↑ Biel 1996, p. 115.

- ↑ Biel 1996, p. 117.

- ↑ Heyer 2012, p. 124.

- ↑ Heyer 2012, p. 125.

- 1 2 3 Aldridge 2008, p. 89.

- ↑ Spignesi, Stephen (2012). The Titanic For Dummies. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 273. ISBN 9781118206508. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- ↑ Simon 5 May 1997.

- 1 2 Spignesi 2012, p. 271.

- ↑ Rasor 2001, p. 124.

- ↑ Anderson 2005, pp. 144–45.

- ↑ Anderson 2005, p. 144.

- ↑ Barczewski 2011, p. 235.

- ↑ Foster 1997, p. 37.

- ↑ Foster 1997, p. 38.

- ↑ Bottomore 2000, pp. 52–53.

- ↑ Bottomore 2000, p. 57.

- ↑ Bottomore 2000, p. 52.

- ↑ Bottomore 2000, p. 65.

- ↑ Bottomore 2000, pp. 65–66.

- ↑ Bottomore 2000, p. 77.

- ↑ Bottomore 2000, p. 72.

- ↑ Bottomore 2000, p. 76.

- ↑ Bottomore 2000, p. 75.

- ↑ Bottomore 2000, p. 98.

- ↑ Bottomore 2000, p. 100.

- 1 2 Bottomore 2000, p. 95.

- ↑ New York Evening World 26 April 1912.

- ↑ Bottomore 2000, p. 96.

- 1 2 Ward 2012, p. 222.

- ↑ Spignesi 2012, p. 267.

- ↑ Bottomore 2000, p. 111.

- ↑ Leavy 2007, p. 153.

- ↑ Ward 2012, p. 221.

- ↑ Bottomore 2000, p. 114.

- ↑ Bottomore 2000, p. 115.

- ↑ Bottomore 2000, p. 125.

- ↑ Bottomore 2000, p. 126.

- ↑ Ward 2012, p. 223.

- 1 2 Heyer 2012, p. 138.

- ↑ Biel 1996, p. 148.

- ↑ Ward 2012, pp. 224–25.

- ↑ Heyer 2012, p. 143.

- ↑ Ward 2012, p. 225.

- ↑ Heyer 2012, p. 147.

- 1 2 3 Ward 2012, p. 226.

- ↑ Street 2004, p. 143.

- ↑ Barnes 2010, p. 175.

- 1 2 Heyer 2012, p. 151.

- ↑ Richards 2003, p. 98.

- 1 2 Heyer 2012, p. 104.

- ↑ Anderson 2005, p. 103.

- ↑ Anderson 2005, p. 171.

- ↑ Rasor 2001, p. 121.

- ↑ Kay & Rose 2006, pp. 152–53.

- ↑ Rasor 2001, p. 120.

- ↑ Parisi 1998, p. 223.

- ↑ Spignesi 2012, p. 269.

- ↑ Ward 2012, p. 228.

- ↑ Kramer 1999, p. 117.

- ↑ Parisi 1998, p. 178.

- ↑ Ward 2012, p. 230.

- ↑ Daily Telegraph 28 March 2012.

- ↑ Semigran 8 February 2012.

- ↑ Eaton & Haas 1999, p. 205.

- ↑ Biel 1996, p. 234.

- ↑ Rasor 2001, p. 77.

- ↑ Rasor 2001, p. 78.

- ↑ Ward 2012, pp. 236–37.

- ↑ Anderson 2005, p. 46.

- 1 2 Bartlett 2011, p. 246.

- ↑ Howells 2012, p. 174.

- ↑ Anderson 2005, p. 20.

- ↑ Anderson 2005, pp. 8–9.

- ↑ Butler 1998, p. 208.

- 1 2 Welshman 2012, pp. 281–82.

- 1 2 Biel 1996, p. 151.

- ↑ Sragow, Michael. "A Night to Remember: Nearer, My Titanic to Thee". From the Current: Film Essays. The Criterion Collection. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ↑ Anderson 2005, p. 7.

- ↑ Rasor 2001, p. 151.

- ↑ Anderson 2005, p. 19.

- ↑ Wade, Wyn (2012). The Titanic : Disaster of a Century (Centennial ed.). New York: Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 978-1616084325. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- ↑ Rasor 2001, p. 81.

- ↑ Rasor 2001, p. 80.

- 1 2 3 Rasor 2001, p. 89.

- ↑ Anderson 2005, p. 68.

- ↑ Anderson 2005, pp. 68–69.

- 1 2 Anderson 2005, p. 61.

- ↑ Anderson 2005, p. 60–61.

- ↑ Anderson 2005, p. 70.

- ↑ Anderson 2005, p. 339.

- ↑ Rasor 2001, p. 88.

- ↑ Anderson 2005, p. 57.

- ↑ Anderson 2005, p. 65.

- ↑ Moby Games: RMS Titanic themed video games

- ↑ http://www.titanichg.com/

- ↑ http://www.kenmarschall.com/

- ↑ Howells 2012, p. 114.

- 1 2 Howells 2012, p. 115.

- 1 2 Foster 1997, p. 57.

- ↑ Foster 1997, p. 58.

- ↑ Foster 1997, p. 60.

- ↑ Eaton & Haas 1995, p. 327.

- ↑ Cartwright & Cartwright 2011, p. 116.

- ↑ Eaton & Haas 1995, pp. 329–30.

- ↑ Maniera 2003, p. 50.

- ↑ Maniera 2003, p. 163.

- ↑ Cartwright & Cartwright 2011, p. 117.

Bibliography

Books

- Aldridge, Rebecca (2008). The Sinking of the Titanic. New York: Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7910-9643-7.

- Anderson, D. Brian (2005). The Titanic in Print and on Screen. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company. ISBN 0-7864-1786-2.

- Barczewski, Stephanie (2011). Titanic: A Night Remembered. London: Continuum International. ISBN 978-1-4411-6169-7.

- Barnes, Julian (2010). A History Of The World In 10½ Chapters. London: Random House. ISBN 978-1-4090-8865-3.

- Bartlett, W.B. (2011). Titanic: 9 Hours to Hell, the Survivors' Story. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4456-0482-4.

- Biel, Steven (1996). Down with the Old Canoe. London: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-03965-X.

- Biel, Steven (1998). Titanica: The Disaster of the Century in Poetry, Song and Prose. London: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-31873-7.

- Bottomore, Stephen (2000). The Titanic and Silent Cinema. Hastings, UK: The Projection Box. ISBN 978-1-9030-0000-7.

- Butler, Daniel Allen (1998). Unsinkable: the full story of the RMS Titanic. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-1814-1.

- Cartwright, Roger; Cartwright, June (2011). Titanic: The Myths and Legacy of a Disaster. Stroud, Glos.: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-5176-3.

- Eaton, John P.; Haas, Charles A. (1995). Titanic: Triumph and Tragedy. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-03697-8.

- Eaton, John P.; Haas, Charles A. (1999). Titanic: A Journey Through Time. Sparkford, Somerset: Patrick Stephens. ISBN 978-1-8526-0575-9.

- Foster, John Wilson (1997). The Titanic Complex. Vancouver: Belcouver Press. ISBN 0-9699464-1-4.

- Heyer, Paul (2012). Titanic Century: Media, Myth, and the Making of a Cultural Icon. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-3133-9815-5.

- Howells, Richard (2012). The Myth of the Titanic. Basingstoke, Hants: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-31380-4.

- Kay, Glenn; Rose, Michael (2006). Disaster movies: a loud, long, explosive, star-studded guide to avalanches, earthquakes, floods, meteors, sinking ships, twisters, viruses, killer bees, nuclear fallout, and alien attacks in the cinema. Chicago: Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-5565-2612-1.

- Kramer, Peter (1999). "Women First". In Sandler, Kevin S.; Studlar, Gaylyn. Titanic: anatomy of a blockbuster. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-2669-0.

- Leavy, Patricia (2007). Iconic Events: Media, Politics, and Power in Retelling History. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-1520-6.

- Maniera, Leyla (2003). Christie's Century of Teddy Bears. London: Pavilion. ISBN 978-1-8620-5595-7.

- Parisi, Paula (1998). Titanic and the Making of James Cameron. New York: Newmarket Press. ISBN 978-1-55704-364-1.

- Pratt, E. J. (1935). The Titanic. Toronto: Macmillan. OCLC 2785087.

- Rasor, Eugene L. (2001). The Titanic: historiography and annotated bibliography. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-3133-1215-1.

- Richards, Julian (2003). A night to remember: the definitive Titanic film. New York: I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-8606-4849-6.

- Spignesi, Stephen (2012). The Titanic For Dummies. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-20651-5.

- Street, Sarah (2004). "Questions of Authenticity and Realism in A Night to Remember (1958)". In Bergfelder, Tim; Street, Sarah. The Titanic in myth and memory: representations in visual and literary culture. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-85043-431-3.

- Sutherland, John; Fender, Stephen (2011). Love, Sex, Death & Words: Surprising Tales from a Year in Literature. London: Icon Books. ISBN 978-1-8483-1247-0.

- Tribe, Ivan M. (1993). The Stonemans: An Appalachian Family and the Music That Shaped Their Lives. Chicago: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-2520-6308-4.

- Taylor, Lance (2011). Maynard's revenge: the collapse of free market macroeconomics. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674050464.

- Ward, Greg (2012). The Rough Guide to the Titanic. London: Rough Guides Ltd. ISBN 978-1-4053-8699-9.

- Welshman, John (2012). Titanic: The Last Night of a Small Town. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-1916-1173-5.

- News articles

- "Riot In Theatre Over Picture Of Sinking Titanic". New York Evening World. 26 April 1912.

- Hughes, Zondra (June 2000). "What Happened to the Only Black Family on the Titanic". Ebony. pp. 148–154.

- Simon, John (5 May 1997). "It Sinks". New York magazine. pp. 83–84.

- "James Cameron denies Titanic 3D release is cashing-in on tragedy". The Daily Telegraph. 28 March 2012.

- Semigran, Ali (8 February 2012). "'Titanic' in 3-D to set sail two days earlier". Retrieved 6 April 2012.